Recruiting women to corporate boards and top executive roles helps businesses find the best people and reach key consumers. There’s a risk that too much focus on doom and gloom, over the lack of such senior women in business, will veer the discussion away from what women bring to the table through greater representation.

The topic of why women are underrepresented at senior echelons of business has received plenty of attention, as have proposals on ways to crack open that durable glass ceiling that sadly keeps a lid on women’s advancement. These discussions have been spirited and useful, and I have been an enthusiastic participant in hopes of gaining and providing further insight.

There’s a risk, however, that in concentrating too much on what is preventing women from gaining equality in boardrooms and at senior executive level, the discussion veers too much into doom and gloom – rather than focussing on what women can bring to the table by greater representation on company boards, executive director positions and other key policy-making roles.

Supporting gender equality in such roles is simply the smart thing to do from a business perspective, in addition to being the right thing to do. It’s worth examining several ways in which bringing more women to top roles can make business function better, attract new customers, and improve the bottom line.

Choosing the Best People

It’s long been recognised in business literature that choosing directors and other top personnel reflects the external environment in which firms operate, so companies have a natural incentive to select among scarce resources for the best possible people.

The best possible people are often identified through networking, word of mouth and other professional contacts, so there’s a virtuous circle at play: attracting more top women to senior roles legitimises a company seeking to attract other qualified women, by demonstrating that they are sought after and welcomed at the firm. At the same time, the inclusion of women at board and other top levels improves a company’s ability to develop channels – including networking opportunities – for identifying and attracting like – qualified women.

As outlined in a working paper I have developed with two colleagues at Cambridge Judge Business School – Elaine Oon and Jenny Chu – women board members’ different perspectives, beliefs and experience sets give them the potential to link organisations to a different set of constituencies, compared to male board members. In addition, female and male directors bring different views on how board decisions should reflect stakeholder – oriented stances – so women directors can help expand channels for connecting to key stakeholders.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Reaching New Customers

Such key stakeholders include women’s consumer markets, so companies that can expand access to and understanding of these channels through greater female representation at top levels stand to benefit through greater insight into women’s tastes, preferences and shopping trends.

Such benefits will differ, however, among various countries.

Our previous research found that a country’s female economic power in terms of participation in education and labour markets is a key factor in female representation on company boards. Likewise, female economic power also leads to greater financial security and therefore greater clout in buying decisions and consumer control.

For example, the Pew Research Center recently found that women in the US outnumbered men in tablet ownership by 47% to 43%, while a separate study in 2010 found that US women control 83% of all consumer spending.

Beyond greater access to important markets such as labour and consumer spending, greater participation by women at top levels of companies brings a hard-to-measure but very important level of legitimacy in the eyes of stakeholders.

That’s because connection to a wider audience of workers and customers creates a higher collective intelligence within firms, bringing even deeper connections to influential audiences. This in turn attracts more qualified people to the firm, enhancing further the networking effect that such women bring. Yet another virtuous circle.

Don’t Just Count Numbers, Make the Numbers Count

Much of my recent research has focused on the factors that contribute to greater equality in boardrooms and top executive ranks, so percentages have been front and centre in such discussions. But the further we have delved into the subject, the more convinced we are that the conversation should shift from merely “counting the numbers” to instead “making the numbers count,” as Boris Groysberg and Deborah Bell¹ put it.

In other words, it’s not merely the quantity of women in top positions that matter, but also whether policies are in place at various levels – company, government and corporate governance codes – to ensure that women can make a true impact in such roles.

Our research found that quotas don’t much contribute to placing and recruiting women to board positions or top executive roles where they can have an influential impact on firm strategy and results. Hard quotas can actually create a hostile environment for intended female beneficiaries by creating an “us-versus-them” environment that stifles women’s social integration in the company. Such quotas can also create perceptions, regardless of the person’s background and skill, that merit has been compromised, and that can muffle their voices and sideline them from key decisions.

This may be the root of a wide discrepancy between board and senior executive representation in countries that have mandated female board quotas – and it is the senior executive suite where women can have the most direct impact on company strategy and practices, and best interact with other women in the firm.

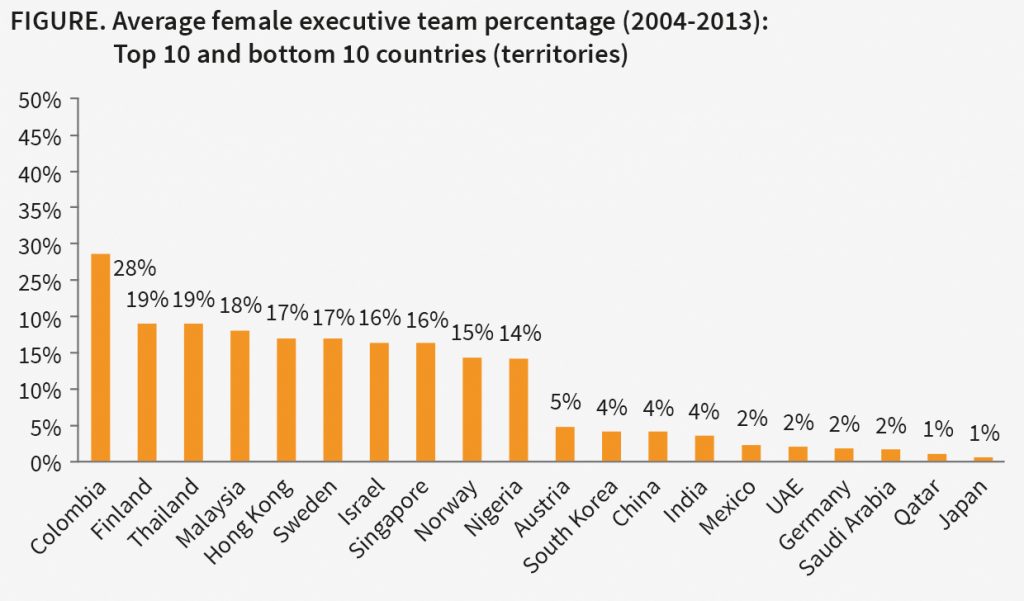

Take Norway. As shown in the graph (see figure below), the Scandinavian country has long been known for its pioneering 40% quota for women on listed company boards, but our study of more than 1,000 companies from 42 countries over a 10-year period (2004-2013) found that Norway ranked only ninth for female representation in top executive roles, at 15%. This lagged well behind such countries as Colombia at 28%, Thailand at 19% and Malaysia at 18%.

Retaining Women Leaders is as Important as Recruiting Them

An important but often ignored aspect of building a gender-inclusive culture is retention of high-potential women in leadership positions.

It is well recognised that the value of human capital grows over time as executives build trusting relationships and develop a tacit understanding of the internal processes of the organisation. In contrast, high turnover is disruptive and leads to considerable brain-drain and loss of value skills, experiences and capabilities.

If firms are to reap the benefits of the diverse perspectives that women bring to decision-making and women are to succeed and make a meaningful impact in board and strategic decision-making, then companies need to invest in retention of women leaders. Yet the issue of retention has not received much attention when it comes to gender diversity on boards and senior executive teams. We found that maternity laws including total length of maternity leave, paid versus unpaid leave, paternity and shared leave, and flexible working arrangements are pivotal in reducing turnover among senior female leadership. Such benefits lend support for women to rise up the corporate ladder and expand the pool of qualified women eligible to serve in senior leadership roles.

Moving Beyond Quotas

So if not quotas, what does work well in elevating more women to executive ranks?

We looked at 56 industries ranging from services to transportation, and found that “soft” measures work far better to bring women to top roles on the executive or management boards of companies, as so indicated by their annual reports.

One such useful soft measure is gender diversity requirements in corporate governance codes, which tend to take on the form as best practice recommendations that pressure companies to do the “right” thing. Countries that specify gender diversity as such a best practice include the UK, the US and Brazil, while India, China and the United Arab Emirates lack such a provision in their codes.

We also found that director term limits were a useful soft measure, because limiting directors to a fixed period reduces board retrenchment and leads to healthy renewal. Beyond addressing gender imbalance, such term limits bring new skill sets to the board and can be used to ease out underperforming directors. Term limit rules vary from strictly mandated limits as in France to “comply-or-explain” regulations in Hong Kong.

Our findings about term limits are particularly interesting. Most previous discussion about term limits has focused on ensuring the independence of non-executive directors, so they don’t become too entrenched on the board; the impact on gender diversity is therefore an important spill-over effect. Though these limits apply to the board, bringing new perspectives and breaking down entrenched board networks helps create a new culture that opens the broader executive suite to more women.

Executive directors play a particularly significant role on strategy and outcomes for two reasons: they have greater access to internal information and company context that impact strategy, and they are full time and have the ability to prepare and participate in detailed matters in a way that part-time non-executive directors may not. So female executive directors will be more visible to both internal and external stakeholders.

Concluding Thoughts

Overall, cumulative research including our research points to the importance of shifting the conversation from a more doom and gloom perspective of “why women fail” to a more positive view of “what women bring to decision-making” and “what organisations can do to unleash this potential”. The ethical (right thing to do) and the business case (smart thing to do) are tightly interconnected. This shift will require moving beyond the gender divide based on quotas and numbers toward a collaborative approach that focuses on impact and sustainability of women leaders.

As an institution that educates the next generation of business leaders, Cambridge Judge Business School is trying to do its part for gender diversity. So a new Women’s Leadership Initiative was launched in 2015 for men and women to work together to foster gender inclusivity in the workforce through insightful research, innovative programmes, and partnerships with a broad set of stakeholders including corporations, policymakers and not-for-profit organisations. As our research and other work collaborations go forward, we plan to continue to analyse the factors that are holding back true gender equality in business, and, hopefully, watch the doom and gloom ebb away as the true benefits of such diversity become crystal clear to everyone.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Author

Sucheta Nadkarni is Sinyi Professor, Head of the Strategy & International Business subject group at Cambridge Judge Business School and Director of the Women’s Leadership Initiative. Her key areas of research include strategic leadership and competitive dynamics between firms. She served as the associate editor of the Journal of Management from 2011-2016, and is currently the incoming associate editor of the Academy of Management Journal.

Sucheta Nadkarni is Sinyi Professor, Head of the Strategy & International Business subject group at Cambridge Judge Business School and Director of the Women’s Leadership Initiative. Her key areas of research include strategic leadership and competitive dynamics between firms. She served as the associate editor of the Journal of Management from 2011-2016, and is currently the incoming associate editor of the Academy of Management Journal.

Reference

1. https://hbr.org/2013/06/dysfunction-in-the-boardroom

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)