By Zhang Shuyue, Hunter Trylch and Xiangming Chen

As geopolitical tensions and tariffs disrupt global trade and supply chains, and businesses worry about eroded markets, fragile logistics, and the uncertain impact of digital technology, the Chinese city of Yiwu embodies these shifting relations as the world’s largest small-merchandise hub.

Global trade and logistical connectivity

Ms. Xu has run a jewelry packaging business in Yiwu for many years. She has witnessed the city’s rapid growth and constant renewal due to its premier status as the top global center for small merchandise. To her, Yiwu’s central market and commercial ecosystem undergird its economic prosperity and trade resilience. Ms. Luo, who manages a coffee equipment shop, relies on her personal network for market information while working closely with factories and suppliers to meet fast-changing customer demands in a competitive market environment.

During China’s recent National Day holiday in early October, when most people were on vacation, Yiwu bustled. Workers rushed to put the finishing touches to the Global Digital Trade Center, and the activity was equally intense in the six-generation district of Yiwu’s massive Futian Market and Yiwu International Trade City, which comprises five successive districts built over the past 40-plus years (photo 1). But how did all of this begin?

A poor rural county through the late 1970s, Yiwu was one of the few pioneers in China’s market reform and opening to trade, along with the special economic zone of Shenzhen, bordering Hong Kong. Farmers became entrepreneurs by bartering some local agricultural goods for others, which earned Yiwu the moniker of “exchanging chicken feathers for sugar.” This origin quickly unleashed a risk-taking entrepreneurial fervor and market dynamism. Farmers in Yiwu supplemented their incomes during the agricultural off-season by crafting and selling small commodities on the streets and in nearby towns. Although this type of street market was technically illegal, farmers were willing to risk losing their goods along with the scarce resources invested in them. This experiment forged a culture of resilience and resourcefulness and an instinct for commerce that would shape Yiwu’s transformation (Zhao & Fan, 2025).

In 1982, under the leadership of the then Party Secretary Xie Gaohua, the Yiwu government opened the city’s first small-commodity market (Yu, 2019). This decision marked a turning point, institutionalizing a practice that had long existed informally and paved the way for what would become the world’s largest small-merchandise wholesale / retail hub. Today Futian Market spans over four square kilometers of commercial floor space, containing more than 75,000 stalls (Miao, 2022) dedicated to the export of small commodities that reach markets around the world.

Yiwu’s trade-fueled economy did not take off by accident. Its local government played an essential role in steering the city’s trajectory, particularly recognizing the critical importance of logistics. In the 1990s, Yiwu began to integrate its trade networks with Ningbo-Zhoushan Port in Zhejiang province, one of the busiest maritime gateways in China. This partnership allowed Yiwu’s small commodities to flow to overseas markets along key international shipping routes. Located in the Yangtze River Delta, China’s largest economic region, Yiwu benefits from being relatively close to China’s and the world’s two largest ports: Shanghai, as the world’s no. 1 container port, and Ningbo-Zhoushan, its largest port for total cargo throughput.

Yiwu’s trade-fueled economy did not take off by accident. Its local government played an essential role in steering the city’s trajectory.

China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 accelerated Yiwu’s integration into the global economy. WTO membership obligated China to lower tariffs, remove non-tariff barriers, and abide by multilateral trade regimes. It granted China “most-favored-nation” status in many markets, most notably the United States, giving Chinese goods more secure access. This encouraged foreign buyers to source directly from Yiwu (Erten & Leight, 2022), which obtained more stable export conditions, less regulatory friction, and stronger incentives for private firms to trade internationally (Xie & Liu, 2021). Yiwu and its surrounding region built bonded logistics centers and processing facilities where goods could be stored or consolidated for final export (Shou, Shi, & Zhang, 2024). These logistical facilities lowered the fixed costs of international shipping, especially for small, export-dependent firms.

In the 2010s, Yiwu strengthened its logistics sector to further expand its global trade ties. The Yiwu–Europe freight railway created direct overland routes to European cities such as Madrid, London, and Duisburg (map 1). This reduction in delivery times over maritime shipping allowed Yiwu to reach consumers and businesses across Eurasia faster (Chang, 2024). Meanwhile, faster rail-sea intermodal links through Ningbo-Zhoushan Port further strengthened Yiwu’s trade connections to the Middle East and Africa.

Map 1. The Yiwu–Europe freight train network

Source: YXE (Yiwu-Xinjiang-Europe) portal. https://www.yixinou.com/en/lines

Upgrading logistics through technological advancement

The rapid expansion of Yiwu’s trade has heightened its demand for logistical support as it adapts to such uncertainties as geopolitical tensions and tariff disruptions. Yiwu’s extensive trade ties across the Global South provide its merchants with greater maneuverability and less reliance on major Western economies, especially the United States, which imported a lot from Yiwu for a long time. The first Trump presidential campaign sourced all MAGA hats and flags in 2015-16 and also ordered more memorabilia than the Biden campaign from Yiwu in 2024. While Yiwu still accounts for 60-70 per cent of Christmas holiday decorations sold in the US, China’s share of exports to the US fell dramatically from 20 per cent in 2018 to just 10 per cent in Q2 of 2025 (DWS Investment, 2025). As a leading trade city of Zhejiang, one of China’s three provinces most dependent on trade with the US, Yiwu has been an integral part of China’s shifting regional orientation toward global trade.

To enhance its trade diversification and flexibility, Yiwu has introduced a large set of e-commerce platforms and other digital technologies. The first major initiative in this regard was the launch of Yiwugo in 2012, which made it possible for all vendors to sell online with a required local registration. In 2019, the Yiwu government and Alibaba Group signed a strategic cooperation agreement that made Yiwu the first choice among China’s top exporting cities for the digitization of industrial chains, trade financing, and smart logistics.

Over the past decade, digital technological advances have facilitated Yiwu’s growth by aligning trade services with logistics development. Logistics in the digital age is no longer just about the physical movement of goods, but speeds up and stabilizes e-commerce transactions and product delivery across borders. Global platforms such as Alibaba, Pinduoduo, and Amazon have raised consumer expectations for low prices and fast delivery. Yiwu stands out in integrating these digital demands with its existing physical trade ecosystem, where online commerce does not replace but extends traditional trade capacity.

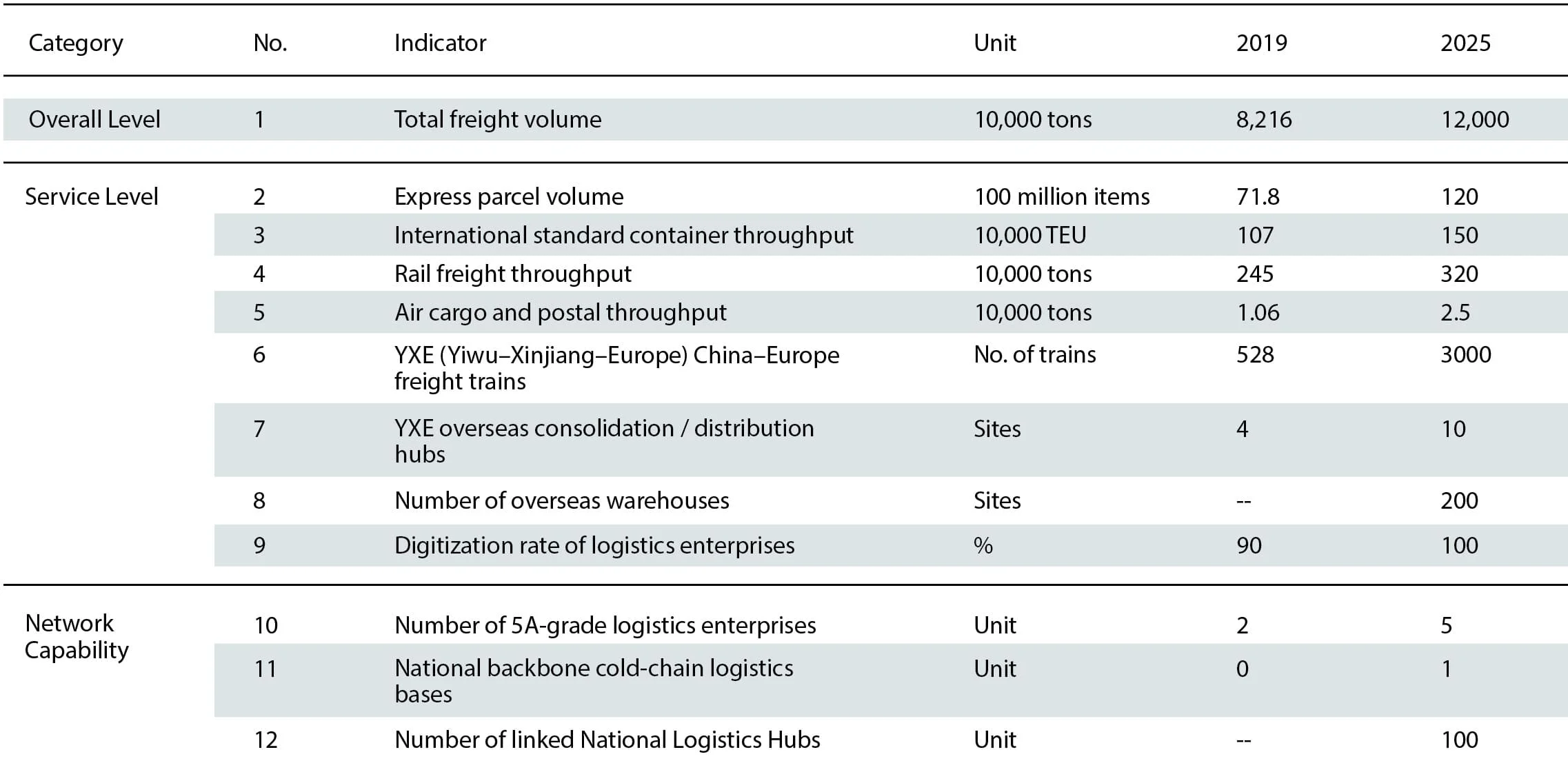

Through its integrated logistical development (table 1), Yiwu has diversified the shipping routes for its expansive global trade ties over time. The COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical disruptions have only underscored the importance of this adaptability.

Table 1: Logistics development indicators under Yiwu’s 14th Five-Year plan (2021-25)

When maritime freight costs spiked early in the pandemic, Yiwu merchants turned to the Yiwu–Madrid freight train, which was launched in November 2014 as the world’s longest freight line, spanning eight countries, approximately 13,000 kilometers, and cross-border gauge changes in Kazakhstan and France. From a few annual runs early on, the Yiwu–Madrid freight train numbered over 1,000 by 2024, a decade later. Now regularized at two runs from Yiwu to Madrid and one run back each month, this line has steadied the shipping of Yiwu goods to Spain and parts of Europe in 18 days, compared with almost two months by sea. It even allows a large discount store on the Spanish island of Gran Canaria, off northwestern Africa, to sell goods from Yiwu.

After the Ukraine War in 2022 partly disrupted the China–Europe freight train routes through Russia and Central Europe via the “Northern Corridor,” Yiwu turned back more to its convenient maritime shipping. In August 2025, Yiwu sent a freight train to Ningbo-Zhoushan Port, where the 50 containers were then transshipped to the Port of Aden in Yemen, in 19 days. This new rail-sea intermodal shipping route benefits about 1,000 Yemeni-owned trading businesses in Yiwu (Zhang, Trylch, & Chen, 2025), as China-registered ships have been largely safe from the threat of northern-Yemeni Houthi militants to the Red Sea shipping channel during the recent Middle East conflict.

In growing and adjusting these global logistical connections, more Yiwu traders have also ramped up their use of WhatsApp, WeChat, Chinagoods, livestreaming, and short-form video platforms to reach and link with more overseas buyers, reinforcing the complementarity between digital commerce and physical logistics.

Conversations with local factory owners and managers reveal a shared emphasis on logistics and digital technology. Because many Yiwu businesses survive on high volumes and low margins, they must mobilize every available resource to stay competitive. One illustration is the informal labor network built through the online communication platform of WeChat. These self-organized groups function as flexible labor pools which allow migrant workers and retirees with limited education to take on such short-term tasks as packaging or moving semi-finished goods. Business employers, in turn, make quick compensatory payments online to ensure efficiency while avoiding lengthy managerial procedures. By embracing these tools, Yiwu has not only met the challenge of digital globalization to in-person business transactions but has also meshed local export / import markets with increasingly digitized global trade.

Critical infrastructure and trade resilience

Market-led expansion in Yiwu began organically. Local farmers seeded the primitive street market through bartering and small-scale sales. Migrant entrepreneurs and traders clustered in the first central market under relatively light local government assistance and regulation (Zhang, Trylch, & Chen, 2025). As this bottom-up marketization scaled up and became global, it called for and received growing and varied infrastructural support from the Yiwu government.

The government’s initial key infrastructural intervention was the construction of large-scale and multi-story buildings. They eventually formed the five districts of the International Trade City, which house more than 75,000 booths where over 200,000 vendors sell their products globally. Auxiliary infrastructural assistance included the construction of multi-story warehouses equipped with freight elevators around the central market for rapid parcel movement and turnover, while other micro-logistical facilities connected to the rail terminal, and trunk roads led to Ningbo–Zhoushan Port. At a finer scale, dense belts of mixed-use spaces converted from ground-floor shop fronts and upper-floor apartments allow people to handle small-batch orders without a significant upfront investment.

Government-enabled infrastructure provided both physical space and logistical capacity, which then allowed the trading market to “breathe” and blossom. Government planners have adopted flexible land supply and adaptive zoning to integrate functions that tend to be isolated or segmented in other cities. Commerce and logistics are coupled along designated corridors for heavy trucks and expanded rail–port intermodal links. In its new Yiwu Spatial Master Plan for 2021-35, the Yiwu government has structured its spatial layout to prioritize logistical infrastructure by building integrated hubs, centers, nodes, and corridors with the goal of enhancing the city’s efficiency and resilience built on its central trade market and commercial ecosystem for global trade.

Government-enabled infrastructure provided both physical space and logistical capacity, which then allowed the trading market to “breathe” and blossom.

Related but beyond its Master Plan, the Yiwu government began building the International Supply Chain and Logistics Center project in March 2025. With the planned use space of 23 hectares and construction space of 250,000 square meters to be completed in 2026, this new project will serve the combined functions of duty-free warehousing, exhibition, inspection, logistical transit, and industrial processing tied to Yiwu’s role as a nodal point on the China–Europe freight train, integral to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Yiwu has extended its logistical connectivity far beyond its local arena. In June 2022, Yiwu Market opened its first overseas branch in Dubai to cover the Middle East, which has a large number of traders based in Yiwu. The Yiwu Market-Dubai covers 200,000 square meters, divided into two purpose-built sections. The first section features 1,600 exhibition halls serving as shopping or trading spaces, while the second section comprises 324 warehouses. In 2025, Yiwu launched the Yiwu–Ningbo–Dubai rail-sea intermodal service to Jebel Ali, UAE. It reduces delivery time from 23 to 17 days and lowers shipping costs by about 18 per cent (Li & Wei, 2025). In late 2025, through Zhejiang China Commodities City Group, Yiwu opened the Yiwu Market Angola in Luanda, the capital city of Angola. This new Yiwu extension offers brand authorization and supply chain integration of business, people, goods, markets, and logistics. It will allow Yiwu to extend and localize its commercial model and logistical connectivity into the African market. Besides these two Yiwu-branded overseas markets, Yiwu has established 62 overseas sales and exhibition facilities in 29 countries.

To add a critical new piece to its expanding critical infrastructure, Yiwu opened the Global Digital Trade Center on October 14, 2025 (photo 2). Costing 8.3 billion RMB ($1.2 billion), the Center, which broke ground in 2022, consists of a central market, an office tower, a commercial zone, a digital trade port, and a group of high-end apartment buildings, whose total constructed space amounts to 1.25 million square meters. The Center’s heart, the large central market, occupies 400,000 square meters, one-third of the total complex (Wu, 2025). It can host around 3,700 vendors, each of which has 30 square meters of operating space, much larger than the typical booth in Districts 1-5, and some of which are equipped with large LCD screens for displaying AI-generated ads. Of the vendors who have already moved into the new central market, the so-called “creative” and new-generation businesses account for 52 per cent, while those owning their brands make up 57 per cent (De, Chen, & Wei, 2025).

The new Global Digital Trade Center prioritizes such product categories as fashionable jewelry, creative and trendy toys, and smart equipment and machinery, especially drones and robotics (photo 3). To feature and advance these higher-value-added and tech-intensive products, the Center has introduced a large model-based digital platform that offers powerful capabilities of AI-assisted product design and pricing, short-video creation, and instant translation of many languages to merchants on their phones and laptops for them to pitch their products to potential buyers. Another digital platform powered by machine learning algorithms collects and computes big data on product features, inventories, shelf time, and sales to help merchants lower transaction costs and increase profit margins by optimizing their supply chains and sales channels. The Global Digital Trade Center represents a strategic upgrading of Yiwu’s traditional market operation and recent e-commerce through large-scale digitalization and AI applications.

Trading up to stay resilient

The Yiwu story is about the miraculous rise of a small rural place to the pinnacle of global small- merchandise trade. This transformation has traveled the intersected path of market, logistics, and digital technology working together to drive hundreds of thousands of small traders working diligently to keep Yiwu highly competitive and resilient in global trade. These traders, many of whom have migrated to Yiwu as risk-taking job-seekers, have improved their lot through hard work and creative efforts. They are market-makers who have either survived or thrived in a cut-throat environment that has also led to many bankruptcies and failures. While they operated at the low end of the global market for small merchandise for years, some of them have benefited from a new round of government-provided infrastructure upgrading, most notably the recent launch of the Global Digital Trade Center.

The Yiwu government has acted as a market-enabler since the outset. It played a purposeful, albeit not dominant, role in centralizing Yiwu’s trade market by building a series of large physical structures to house the ever-growing number of small traders. In addition, the local government has provided both logistical and digital infrastructures to render the trade market more favorable for traders. By turning Yiwu into a key hub for the China–Europe freight train, the government has created more diverse and flexible shipping routes for traders. By launching the new Global Digital Trade Center, the Yiwu government has provided powerful digital platforms for traders to create more differentiated and higher-quality products that can reach more discriminating global consumers.

As global trade has turned more unfavorable due to geopolitics and tariffs, Yiwu stands to weather these headwinds as a model of how to keep trade resilient by trading up through market improvement, logistics development, and digital technological advancement.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Fan Lizhu and Dr. Wang Shuqiao at Fudan University, Professor Zhu Yaxiong at Zhejiang Normal University, and Ms. Xu. Ms. Li, and Ms. Chen in Yiwu for helping us with field interviews from the end of June and to early August, 2025. Wu Suchang ’23 and Mr. Al-Yousifi and his brother Basen helped us better understand Yiwu’s development. Hunter Trylch’s research in Yiwu was supported by the Thomas Urban China Endowment at Trinity College, Connecticut. Xiangming Chen’s research was supported in part by the Paul E. Raether Distinguished Professorship Fund at Trinity College.

About the Authors

Zhang Shuyue is a scholar and researcher in Urban Studies based in Shanghai. He holds a Master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania in Urban Planning and Policy and a Bachelor’s degree in Urban Studies and History from Trinity College. He is currently working on a project in a research group at Tongji University focused on regional integration in the Yangtze River Delta. He is also an avid freelance photographer.

Hunter Trylch is a sophomore student at Trinity College, majoring in Economics while minoring in Chinese and Urban China Studies. Hunter learned Chinese during his early education in Hainan, China, and in 2014 moved to Washington, DC, where he is based today. He makes yearly trips back to China, preserving his cultural ties and Chinese-speaking capacity.

Xiangming Chen is Paul E. Raether Distinguished Professor of Global Urban Studies and Sociology at Trinity College in Connecticut and an Associate Fellow at the Center for Advanced Security, Strategic and Integration Studies (CASSIS) at the University of Bonn, Germany. He has published extensively on urbanization and globalization with a focus on China and Asia as well as a frequent contributor on “China in the World” to The European Financial Review and The World Financial Review. He has also conducted policy research for the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, UNCTAD, and OECD.

References:

-

Chang, S. (2024, December 24). “China’s small commodity hub Yiwu connects to global markets”. People’s Daily Online. Available at https://en.people.cn/n3/2024/1224/c90000-2

-

De, B., Chen, J., & Wei, J. (2025, October 14). 现场直击!义乌全球数贸中心开业首日 [Onsite coverage of the first day of the opening of Yiwu Global Digital Trade Center] [WeChat article]. WeChat Public Platform. Available at https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/RsrOg8u51D8JvJby18xIKA

-

DWS Investment GmbH (2025, August 5). “China’s trade thrives beyond the U.S.”. Available at https://www.dws.com/en-us/insights/cio-view/charts-of-the-week/2025/chinas-trade-thrives-beyond-the-us/

-

Erten, B., & Leight, J. (2022, February 7). “Impact of WTO accession: Structural transformation in China”. VoxDev. Available at https://voxdev.org/topic/trade/impact-wto-accession-structural-transformation-china

-

Li, P., & Wei, Y. (2025, May 18). 义乌至迪拜“铁海快线+中东快航”班列成功首发 [Yiwu to Dubai “rail-sea express + Middle East fast ship” train successfully launched]. China Belt & Road [Yidai Yilu]. Available at https://www.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/09JHQKCI.html

-

Miao, Q. (2022, November 24). 不惑之年:义乌市场凭什么买卖全球? [In the forties: Why can Yiwu market buy and sell globally?]. Yicai. Available at https://www.yicai.com/news/101605207.html

-

Shou, X., Shi, Q., & Zhang, X. (2024). “The adaptation and transformation of Yiwu’s foreign trade enterprises amid major changes unseen in a century (2001–2021)”. Transnational Corporations Review, 16(4), 200080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tncr.2024.200080

-

Wu, F. (2025, October 13). 义乌全球数贸中心正式开业!开启数字贸易新时代 [The opening of Yiwu Global Digital Trade Center] [WeChat article]. WeChat Public Platform. Available at https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/iqesEkFrduOqUIeC1RAL9g

-

Xie, J., & Liu, Y. (2021, December 7). “WTO entry a milestone for China: Yiwu traders”. Global Times. Available at https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202112/1240898.shtml

-

Yiwu Government (May 18, 2022). Yiwu Government’s 14th Five-Year Plan for Developing a Modern Logistics Industry.

-

Yu, J., & Feng, H. (2025, January 13). 霍尔果斯义乌国际商贸城转型跨境电商直播探出新机遇 [Horgos Yiwu International Trade City’s transformation into cross-border e-commerce livestreaming reveals new opportunities]. China’s Belt & Road [YidaiYilu]. Available at https://www.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/0TKORPSG.html

-

Yu, S. (2019, July 31). 谢高华:一切从百姓利益出发 [Xie Gaohua: Everything starts from the people’s interests]. Zhejiang News. Available at https://zjnews.zjol.com.cn/zjnews/zjxw/201907/t20190731_10698684.shtml

-

Zhang, S., Trylch, H., & Chen, X. (2025, September 5). “Yiwu: How a barter town became the heartbeat of global small trade”. ThinkChina. Available at https://www.thinkchina.sg/economy/yiwu-how-barter-town-became-heartbeat-global-small-trade

-

Zhao, C., & Fan, L. (2025). 义乌模式:老百姓版本的全球化 [The Yiwu model: People’s globalization]. The Wealth of Nations, 148–157.