By Sean Culey

Issues of corporate culture have long been of great concern to executives and management theorists alike for a simple reason; culture matters – enormously. In this two part article, Sean Culey will first take a close look at organisational culture and the impact it has on leadership effectiveness and business performance, and in the second part, published in the next edition, he will describe what steps leaders can take to address any cultural issues in their organisation in order to create a highly effective, integrated, continuous improvement focused, high performing team.

Culture: Still Dining Out on Strategy?

Every organisation has its own unique culture; defined as the set of deeply embedded, self-reinforcing behaviours, beliefs, and mindset that determine ‘the way we do things around here.’ People within an organizational culture share a tacit understanding of the way the world works, their place in it, the informal and formal dimensions of their workplace, and the value of their actions. It controls the way their people act and behave, how they talk and inter-relate, how long it takes to make decisions, how trusting they are and, most importantly, how effective they are at delivering results. Culture affects staff retention, external perception and financial performance in every type of organisation, be they public or private. In a recent article1 the new head of the Metropolitan Police, Bernard Hogan-Howe, was quoted as saying, “…the culture of an organisation can put shackles on it; if only we did some things quicker, were a bit more imaginative, cut to the quick and encouraged people to take risks.”

How important is Culture, really?

Leaders need to wake up to the power of Culture. Often misunderstood and discounted as a soft, nice-to-have component of business, culture is neither intangible nor fluffy; it is one of the most important drivers to the creation of long-term, sustainable success. Studies have shown again and again that there may be no more critical source of business success or failure than a company’s culture – it trumps strategy and leadership every time. Peter Drucker’s famous quote “culture eats strategy for breakfast” isn’t declaring that strategy doesn’t matter, but rather that the particular strategy a company employs will only be successfully executed if supported by appropriate cultural attributes. Culture is completely within the capability of the business to control and shape, yet often is ignored, with leaders instead focusing on short-term activities like cost-cutting and inadvertently choosing to create an environment where long-term strategic success is less likely.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

Culture isn’t defined by nice sounding values and mission statements posted on the wall or website – it is defined by the behaviours and principles being practised every day, from the Boardroom to the shop-floor. As an example, Enron proudly showcased the company’s core values of Integrity, Communication, Respect and Excellence in beautifully-etched marble in the lobby of their Houston headquarters. Given their subsequent fall from grace through NOT practicing any of these values, this would be funny if it weren’t so sad. While obviously an extreme example, Enron’s approach to values is unfortunately quite similar to many organisations across the world. I am dismayed at how often I find behaviours within an organisation that are completely contrary to those displayed on their website. Engagements with these companies can be painful, as trust levels are generally low, people’s opinions and feelings are guarded, politicking is rife and levels of frustration are high. Everything takes a long time and is expensive, both emotionally and financially. From the leaders down, people go through the process but demonstrate little emotional connection to the success of the organisation, only to their own success and security within the organisation. Whilst not malicious in intent, it is obvious to an outsider that their agenda is more important than the overall company’s agenda. When a whole organisation works like this, we find that levels of activity are high, but levels of achievement are low.

The impact that this has on a company’s ability to deliver results is something that executives are beginning to recognise. A recent global study by the Conference Board2 found that the top two concerns amongst top executives were as follows:

• Excellence in execution

• Consistent execution of strategy by top management

Why the concern on execution? Because organisations that cannot execute their most important goals must call into question whether their executives have the ability to successfully lead. Leaders who fail to mobilise and motivate the organisation to consistently execute the organisation’s most important goals with urgency are ultimately ineffective. John P. Kotter, Professor of Leadership at Harvard, identifies this ‘sense of urgency’ as the most important of his eight stages of effective change3. He cites leader’s underestimation of the difficulties of driving people from their comfort zone and their fear of failure as major causes of a lack of urgency.

Similarly, a 2010 study called ‘Supply Chain Strategy in the Boardroom‘4, asked Supply Chain executives in 181 different organisations to list their main barriers to success. The number one reason quoted was their company’s culture, followed by lack of leadership, lack of information and a lack of CEO support. If culture is the number one barrier to success and if we accept the term ‘culture’ is short for ‘the way we do things round here’, then ‘the way we do things round here’ appears to be the main barrier that stops companies from achieving their long term goals. Yet this is within the control of the organisation, so either the executive leadership doesn’t see the issue or they do not know how to change it.

Why Do Sub-Optimal Cultures Develop?

A number of key characteristics are commonly visible in organisations with sub-optimal cultures:

• Lack of guiding vision, goals and purpose

• Bureaucratic, misaligned systems, polices and processes

• Underutilised and demotivated talent and potential

• Low trust

To understand why these types of organisational cultures develop one does not have to look far; it is because historically businesses have been designed that way. These cultural characteristics are often an unwelcome by-product of ‘command-and-control’ management styles, traced back to Fredrick Winslow Taylor’s ‘Principles of Scientific Management’ and which formed the prevalent management style of the 20th Century. This style worked well for a long time for two reasons; it resolved the major issue of how to control and increase the efficiency of a manual based workforce, and the Leader > Manager > Worker hierarchy simply mirrored the societal hierarchy of Upper > Middle and Working classes.

So why now, in the 21st Century, does command-and-control management still exist? It exists, because, despite all the rhetoric, most organisations are still bureaucratic, centrally planned and hierarchical, set up to take orders from above rather than the customer. According to the Chartered Management Institute5 only 17 per cent of the 1,500 managers polled said that their management was innovative and only 15 per cent said trusting. Command-and-control is unsurprisingly also the prevalent management style practised in the emerging economies of China and India, again due to the fact that the overriding need is to control a workforce of poorly paid labourers. Gary Hamel highlights this issue in ‘The Future of Management’6: ‘Right now, your company has 21st-century Internet-enabled business processes and mid-20th-century management processes all built atop 19th-century management principles.’

‘It’s easy to look good in a boom’ – The Impact of the Recession

Globalisation and the economic downturn has changed the nature of business, bringing increased levels of fear, uncertainty and risk that has left many business leaders feeling exposed and constantly seeking validation through producing increasingly short term results. Whereas a booming economy, with its wide margin of error, can mask and even exacerbate a company’s problems; economic downturns tend to expose these operational inefficiencies and poor management practices. As Warren Buffett once declared; “It’s only when the tide goes out that you see who’s swimming naked” – and the tide’s been out a while now.

The main issue is the lack of will to develop a strategy that can balance today’s need versus tomorrows. Focusing purely on the short term takes away planning for the long term; people concentrate on moving ‘away’ from pain, and not ‘towards’ growth and progression, compromising future growth to survive today. In many, this has created an unwelcome revival of command-and-control, due to the pressure on executives to satisfy impatient investors, keep demanding customers at bay and get the job done more quickly, efficiently and with fewer resources. Professor Cary Cooper, from Lancaster Business School, believes that Boards seem to feel they need a ‘robust’ management style to deliver bottom-line, short-term results. Cooper is quoted as saying7: “from shop-floor to top floor, there’s pervasive employment insecurity: long hours, people as disposable assets, no psychological contract – we’ll pay you OK as long as you’re delivering, but don’t expect any employment commitment in return”. Cultural ineffective organisations don’t work very well – they can’t – and in uncertain times the knee-jerk reaction is to tighten the reins, not slacken them.

The Rise in Tribal Behaviours

The combination of increased ‘command-and-control’ management and employment insecurity creates a perfect environment for poor cultural behaviours to appear. In these circumstances ‘blame cultures’ develop, so when issues arise, and in order to protect themselves, groups form into ‘tribal functions’, focused on protecting their security at the expense of others. Ray Immelman explored the concept of organisational tribal behaviour in his book; ‘Great Boss, Dead Boss’8, applying his tribal model to what is essentially a simplification of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, with individuals seeking both security and value. Where Maslow proposed psychological, safety, and love/belonging needs, Immelman proposes individual security, observing that “individuals act to reinforce their security when under threat.” Where Maslow proposed esteem, Immelman proposes individual value, declaring that “Individuals only act to reinforce their self-worth when their security is not under threat.”

He characterises how tribal behaviours thrive in insecure organisations where protecting individual and tribal values and security is paramount: protect the tribe, protect the status quo, destroy and undermine those who challenge. An organisation of people thinking primarily of their own needs becomes very emotionally disengaged from the organisation as a whole. To break this cycle requires what Jim Collins called ‘Level 5 Leadership’9 – leadership with personal humility and the courage to put their own fears and needs to one side and focus on creating and maintaining a culture of support and continuous improvement. However managers and leaders concerned about their own security and status are not really subject to humility – and insecure and self-serving leaders making decisions primarily to protect their own positions, creates an insecure and self-serving workforce.

The results can be toxic and startling. A FranklinCovey survey on an organisation’s ability to successfully execute strategy, polled 12,182 people about what it was like to work in their organisation, how empowered they felt and how good the working environment was. 65 per cent of people believed that their colleagues undermined them, 61 per cent felt decisions were made for political reasons, nearly 50 per cent felt unable to share their thoughts and opinions, and only 30 per cent felt that they operated as a team.

Whilst I do not fully accept all of Immelman’s observations in regards to tribal behaviour within organisations, his concept that individuals act to reinforce their security when under threat, and only act to reinforce their self-worth when their security is not under threat rings true. When individual and functional security is low, emotions run high and people’s desire for self-worth and to satisfy their psychological needs take over. An easy way to elevate their own position is by highlighting weakness or blame elsewhere, and much energy is expended in the name of self-preservation and retaining their sense of value. People defend what they think they know; over-estimating the value of what they have and under-estimating the value of what they may gain by giving it up. Feeling emotionally disconnected from the organisation, people generally believe that their ability to affect direction and decisions is limited, so instead focus on raising their profile by providing evidence of their importance to the organisation. This emotion driven behaviour creates an increasingly ‘short term’ area of focus, with management teams constantly looking to prove their worth. In these environments any attempts to change are often resisted and undermined if it is felt that it doesn’t directly promote the values of the tribe, or if it weakens security (for example by changing roles or responsibilities). This creates a self-fulfilling prophecy; more management is required to control this behaviour, which validates the use of a ‘Command-and-Control’ approach, which in turn generates higher levels of employee disengagement.

I have unfortunately run into this issue headfirst in my own consulting engagements – with painful results. In these low trust cultures everything costs more and takes longer. The ability to recognise this behaviour early has made a huge difference to my ability to help leaders enable business transformations.

Culture, Innovation and Talent

In a time when the main sources of competitive advantage are knowledge and innovation; one of the most damaging aspects of a poor culture relates to the organisations ability to attract, retain and develop top talent. A dysfunctional culture can drive your best talent away; an exciting, supportive, and empowering one can attract and retain them. Four-fifths of organisations have problems finding and keeping the right people, according to research from the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD)11. They state that employers risk losing talented workers to other companies should they fail to tackle distrust in senior management, leaving them with under-qualified or at least inappropriately-qualified, staff. Claire McCartney, from the CIPD, states that, “overall, trust in leaders is low, with 38% of employees saying that they did not trust their senior management team. With many organisations facing tough times, issues such as organisational culture and values often ‘take a back seat’ ”. This is a mistake.

A recent Forbes article called ‘Top Ten Reasons Why Large Companies Fail to Keep Their Best Talent’12 highlighted that the top reasons were ‘Big Company Bureaucracy’ and misalignment between the culture of the organisation and the employee’s desires and vision. In a world where competition for talent is global, star performers seek companies with values that mirror their own. Other cultural reasons included:

• Shifting Whims/Strategic Priorities

• Lack of clear organisational Mission/Vision

• Lack of Accountability

• Lack of Open Mindedness

Digital age businesses are not immune from cultural inefficiencies. Zynga is the world’s largest social gaming company with an active user base of more than 200 million users, and claimed revenues in excess of a billion dollars in 2011 from selling in-game, virtual goods. Zynga also has a command-and-control, top-down leadership style, which, according to a New York Times article13 has frustrated many Zynga employees with its long hours, stressful deadlines and aggressive culture. The article highlights how feudal, tribal states have developed within the company and raises a concern that as the level of discord increases, the situation may jeopardise the company’s ability to retain top talent at a time when Silicon Valley start-ups are fiercely jockeying for the best executives and engineers.

“We’ve learned that when companies treat talent as a commodity, the consequences are severe”, said Gabrielle Toledano, head of human resources for Electronic Arts, a company that, according to the article, is waiting in the wings to relieve Zynga of its best talents. The message is clear – if you can’t provide an environment for top talent to flourish and grow, someone else will.

The Upside of Culture

So far we have explored the debilitating impact a poor culture has on an organisation – however the reverse is also true – strong cultures create strong organisations. The dominance and coherence of culture is an essential quality of excellent companies – the more cohesive the culture and the more it is focused towards delivering value to the customer, the less need there is for policy manuals, organisation charts, detailed procedures and rules. The best companies and the best leaders understand the real drivers of business success: a long-term perspective which focuses on customer and employee relationships as the sources of competitive advantage and an emphasis on values and ethics as guides to decision making.

In his latest book, ‘The Culture Cycle’14, Prof. James L. Heskett states that effective cultures can create between 20-30 per cent uplift in corporate performance when compared with ‘culturally unremarkable’ competitors. When asked which elements create the most benefit, companies ranked culture at 80 per cent and recruitment/retention at 70 per cent. Competitiveness, customer loyalty, innovation, and productivity – while critical to daily operations – scored less than 20 per cent each.

The 2011 Booz & Company Global Innovation 1000 Study titled ‘Why Culture is Key’15, highlighted how only 44 per cent of companies reported that their culture and innovation strategies were clearly aligned with their business goals. However these organisations delivered 33 per cent higher enterprise value growth and 17 per cent higher profit growth than those lacking such tight alignment.

The findings of the study found that having a strong supportive culture is the primary key to innovation success, and its impact on performance is measurable. Companies with unsupportive cultures and poor strategic alignment significantly underperform their competitors, whereas the report stated that ‘companies whose strategic goals are clear, and whose cultures strongly support those goals, possess a huge advantage’. The report also commented that, ‘if more companies could gain traction in closing both the strategic alignment and culture gaps to better realise these goals and attributes, not only would their financial performance improve, but the data suggests that the potential gains might be large enough to improve the overall growth rate of the global economy’.

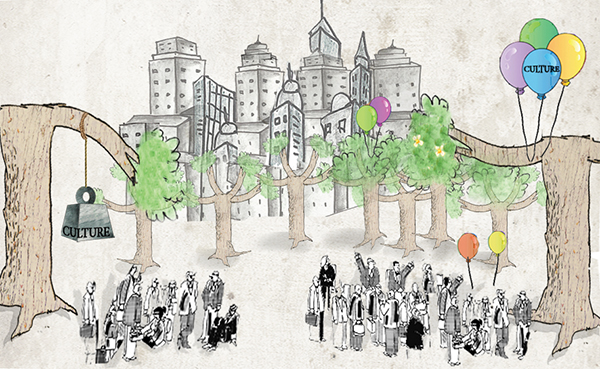

Your Culture: Dragging People Down, or Lifting Them Up?

In previous articles I have promoted the concept of ‘T’ shaped people, teams and organisations – people with business breadth AND functional depth who can work together as an aligned team to deliver a common goal, eliminate distrust, break down functional barriers and develop joined-up, integrated and value focused processes and solutions.

Recruiting top talent is one thing; appropriately deploying them and getting them to integrate, collaborate and play nicely together is something else entirely. A weak, toxic, organisational culture effectively acts as weights that drag down the arms of the ‘T’, turning ‘T’ shaped people into ‘I’ shaped ones who are focused only on their department, function or individual needs.

When people who are intrinsically ‘T’ shaped, feel the culture dragging them down into an ‘I’ shape, they initially fight against it, trying to demonstrate that there is a better way of operating. When this happens they may become frustrated, and then, realising they are fighting a losing battle, they may either choose one of the following responses;

(1) Quit but stay. According to Gallup16, 23 million people in the U.S. are ‘actively disengaged’ from their work. Result – millions of workers have resigned themselves to their jobs; they turn up and do their job at a basic level, but that’s all. It’s not so much what they do; it’s what they don’t do. In the US alone, the estimated the cost of this lost productivity exceeds $300 billion.

(2) Leave. 47% of employees who said that they strongly distrusted their directors or senior managers were looking for a new job, compared with fewer than one in 10 (8%) of those who said that they trusted management

Conversely, strong supportive cultures act as balloons, lifting up the arms of the ‘I’ shaped people and encouraging them to integrate and work together for the good for the organisation. People who resist have to consciously make the decision to metaphorically keep their arms by their side, and in doing so identify themselves as the ‘wrong people’ that should be removed from the corporate bus as soon as possible.

Many ‘T’ shaped people become ‘I’ shaped due to the culture; but unfortunately not many businesses focus on turning ‘I’ shaped people into ‘T’ shaped ones.

Changing Culture

To ensure their corporate culture provides sustainable competitive advantage, leaders must ensure that their culture is adapting to the changing business environment. Downturns should be seen as opportunities to progress – but first a company needs to be willing and able to adapt. To paraphrase the old joke: “How many experts does it take to turn around a big company? Only one–but the company has to really want to change.” Culture is a choice, not an inheritance.

You cannot simply copy another company’s culture. However there are some fundamental elements that can be put in place to ensure that your organisation can develop a culture that creates sustainable competitive advantage. It is about closing the gap between strategy and execution with employee behaviour linked to the delivery of strategic goals and behaviours designed to focus on adding value to the customer.

The case for Culture is clear. The challenge now is for leaders to have the courage to resist short term pressures and instead look inwards at the culture of their organisation in order to ask difficult but essential questions about how they can change mindsets and create an environment that allows for greater alignment and integration. They need to:

• Allay fears around security and instead focus on ensuring their people can clearly associate the relationship between their roles and responsibilities and strategic value

• Identify and address whether there is a command-and-control management style at play, restricting the abilities of their best people to deliver

• Encourage healthy debate and dialog, not just consensus management, group-think or blind obedience

• Leverage tribal behaviours by moving focus away from silo functions and towards integrated Value Chain tribes, focused around the delivery of customer value

• Develop an environment where the culture encourages and supports the development of ‘T’ shaped teams and individuals

• Lead by example, put aside their own self-interest and fears around position and instead focus on the growth and prosperity of the organisation as a whole

It is about having clarity of focus, developing a longer term view, developing a mindset of continuous improvement and recognising that delivering an environment where talent can thrive and perform well as a team is more important than having the latest tools or reports. No matter how good your strategy is, when it comes down to it, people always make the difference.

In the next part of this article, I will discuss the steps that can be taken to put these measures in place and develop a cultural environment designed to attract and retain the best talent and provide guidance, goals and processes to ‘bake in’ these ways of working, and achieve sustainable competitive advantage.

About the author

Sean Culey is a member of the European Leadership Team of the Supply Chain Council, the global, not-for-profit centre for Supply Chain Excellence, and founder of Aligned Integration Ltd. Previous to this he was CEO for SEVEN Collaborative Solutions, and Principal at Solving Efeso.

Sean Culey is a member of the European Leadership Team of the Supply Chain Council, the global, not-for-profit centre for Supply Chain Excellence, and founder of Aligned Integration Ltd. Previous to this he was CEO for SEVEN Collaborative Solutions, and Principal at Solving Efeso.

Sean has worked around the globe helping companies create dramatic increases in profitability and growth, breaking down their barriers to success through the alignment and integration of their people, processes, systems and data. He helps companies to navigate the journey from functional silos, creating foundations of control that enable continual improvement and innovation via his ‘Aligned & Integrated Organisations’ (AIO) approach designed to create end-to-end, integrated customer and profit focused Value Chain teams. This approach also helps companies align their Integrated Business Planning, Management and Execution processes. He also has 20 years’ experience of creating value from ERP investments such as SAP, and is an expert in helping companies to understand how to realise the value of these investments.

Sean is a frequent conference chair, speaker and author with many published articles on Organisational Greatness, Cultural Change, ERP and Value Chain excellence. His book ‘Becoming Great (by taking everyone with you) – Developing the Aligned and Integrated Organisation’ is due to be published late 2013.

He can be contacted via his company Aligned Integration at sean@seanculey.com

References

1.London Evening Standard, 15 Sept 2011 ‘Dixon of Dock Green is my role model – police workers are not social workers’

2.Conference Board, 2009

3.John P. Kotter; ‘A Sense of Urgency’, Harvard Business Press, 2008

4.Cranfield University & Solving Efeso; ‘Supply Chain on the Boardroom Agenda’ 2010

5.Chartered Management Institute; Quality of Working Life report 2007

6.Gary Hamel and Bill Breen; ‘The Future of Management’, 2007 Harvard Business Press

7.Article: The Guardian, 16 Dec 2007 ‘Command, control… and you ultimately fail’

8.Ray Immelman; ‘Great Boss, Dead Boss. How to Exact the Very Best Performance from Your Company and Not Get Crucified in the Process’, 2003 by Steward Philip International

9.Jim Collins; ‘Good To Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap… and Others Don’t’ Random House Business; 2001

10.FranklinCovey xQ (Execution Quotient) Survey results, 2003

11.Chartered Institute of Personnel & Development, (CIPD): ‘Employers that ignore trust issues and stress among employees risk losing top talent’ Oct 2011

12.Eric Jackson, Forbes, December 2011 ‘Top Ten Reasons Why Large Companies Fail to Keep Their Best Talent’

13.Article: New York Times, Zynga Stock Should Be Above $10 But Corporate Culture Puts A Lid On Growth

14.James Heskett; The Culture Cycle: How to Shape the Unseen Force that Transforms Performance. 2011

15.The 2011 Global Innovation 1000: ‘Why Culture is Key’ Jaruzelzki, Loehr, Holman, 2011

16.Gallup; Employee Engagement Survey Results, 2012

[/ms-protect-content]