By Chris Nichols, Philippa Hardman and Michael Chaskalson

Earlier articles in this series have introduced Team Mindfulness using the AIM model and explored how the application of the model in practice addresses important areas of organisational life, including the creation of a genuinely human organisation as part of the living system of this planet.

This article takes another turn and addresses a question that concerns every organisation we work with. How can we really change the pattern on diversity and inclusion? If we are serious about making our organisations work for everyone, what do we need to do? We think that mindful practice using the AIM approach can be powerful, and this article shows how.

What’s the problem?

Diversity and difference matter. The evidence seems clear: more diverse organisations produce better results. Having a richer mix of perspectives and life experiences allows a company to see more of the system it is working within and to respond to threats and opportunities with a wider imagination around possibilities. Published evidence shows that diverse teams also make better risk and investment decisions.

Despite this, it seems that organisations struggle to build significant diversity and difference, particularly at the more senior levels. Bluntly put, organisations look very similar when it comes to top management.

The latest UK research is bleak. The FTSE 100 currently has no black CEOs, Chairs and Finance Chiefs. There are also currently no black CPOs (HRDs) in the FTSE 100. “In short not one black person holds the strategic keys of change in the FTSE 100,” says Frank Douglas of (FIRM).

This is, of course, only one kind of diversity. There are many others. In some instances, there is improvement. For example, the latest research on women in leadership shows that the proportion of women in FTSE boardroom roles has risen by 50% in five years. The Hampton-Alexander review established a target that 33% of board roles should be women, and 63% of companies have met or exceeded this target. However, a wider target of having a third of women in a broader category of senior executive roles has yet to be met. There is also still an issue of progression to senior roles. For example, in medicine, although half of all doctors are women, only 25% of medical directors are women, and only 13% of clinical professors. The pattern is similar in other fields. There remains work to do.

Another area of difference is in the sphere of LGBTQ+ and here concerns are starting to get more serious organisational attention. But others, including some aspects of physical capacity, and many aspects of neurodiversity (for example, autism, ADHD), get far lower levels of targeted attention in most organisations. An estimated 1 in 7 people in the UK are neurodiverse but this isn’t currently routinely acknowledged in most of the workplace.

Slow progress, and in some cases stalled progress, means that many organisations still suffer from insufficiency when it comes to including richly different perspectives regarding their problems and challenges. There is a risk that the issue is self-perpetuating. Until there is sufficient difference to create a critical mass for appreciating the value of that difference, the going is tough.

So, it remains a difficulty and it is important that we shift the game. Perhaps the time has come for a creative new framing to help things move? We think so.

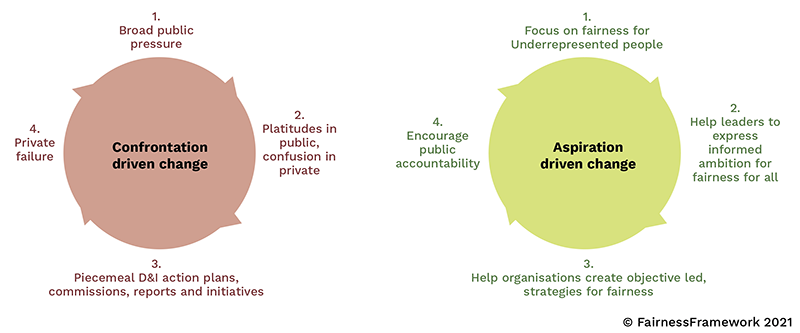

One of the best pieces of analysis we have seen is the work of the Fairness Framework developed by the UK consultants Cedi Frederick, Ruchi Singh and Damola Timeyin. They have been active in advancing progression around diversity and inclusion for many years, both in leadership roles and as consultants. Their work, and their frustration at the sometimes slow progress, led them to a valuable insight. They concluded that much of the argument had become enmeshed in a “confrontational cycle”: guilt in the face of public pressure led to a raft of high-sounding public statements that are often backed by piecemeal initiatives and dissipated organisation effort that doesn’t quite garner sufficient priority and support.

They suggest a reframing, to create a more aspirational cycle built on a shared will to create fairness for all under-represented groups. A fact-based focus on fairness helps to create organisation-wide, evidence-based strategies with measurable performance in key areas including recruitment, remuneration, progression, wellbeing, allyship and leadership.

We have been deeply impressed by the work of the Fairness Framework team and immediately saw how this framework, alongside the AIM methodology, would be a powerful combination for anyone wanting to take diversity and inclusion seriously, in all its richness of meaning.

How does that work?

A reminder of the AIM approach

We don’t assume that everyone has read the earlier articles in this series, so for anyone who needs it here is a summary of the AIM model.

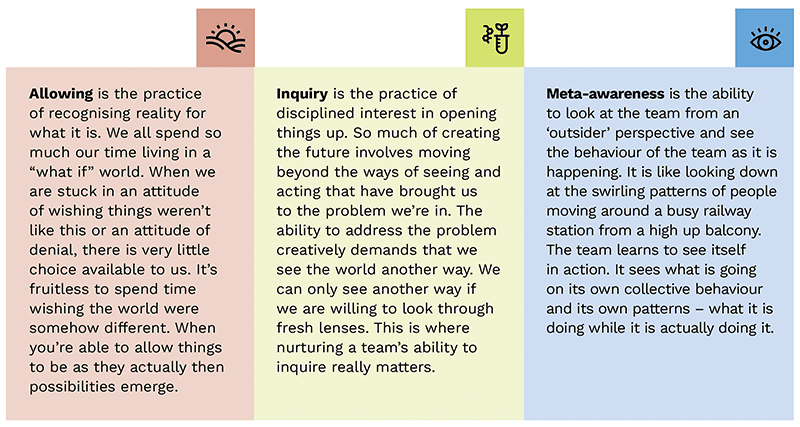

These AIM foundations of Allowing, Inquiry and Meta-awareness were first set out in earlier research discussed in an article by Michael Chaskalson and Megan Reitz.

As we discussed in our previous article, the three fundamentals of AIM – allowing, inquiry and meta-awareness – can all be learned and nourished. Let’s now see how they work in the context of the challenge of creating a more human organisation.

Applying the AIM model to this problem

The first step is Allowing.

The first fundamental step is to acknowledge what is going on, right now, in respect of fairness for all under-represented groups in your organisation and team.

The most important thing is to start from where you are, and it is possible that you genuinely won’t know where that is. Some large and well-resourced organisations have teams devoted to the measurement of diversity and inclusion in all its facets, but most of us do not. In all likelihood, many of us will need to face the fact that we haven’t given this much attention, or that we have focused only on one or two aspects of diversity and inclusion – perhaps gender or race – and have missed others. Allow it. Start where you are, then set about finding out what you don’t know and set about filling the gaps.

There will inevitably be various forms of defence such as inertia, denial and confusion. Some people will not see an issue at all. Others will see it, but deny that it affects us, here, in this team. Others will see the need to do something, but not want to do things that affect the way we operate here and now. Others will be keen to act, but have no idea what to do, or will be genuinely keen to do the right thing and be paralysed by the fear of “getting it wrong”. Every one of these reactions can be expected. The point is to accept them all. It is what it is. Accepting it is the first step of change.

You will certainly need to allow genuine emotions arise to be acknowledged. The whole point of this agenda is to accept that organisations have been, and are, unfair. Those of us who are in senior positions will not relish the fact that many of the cards may have been stacked in our favour from the start. Some people in your team and organisation may feel guilt, may feel unfairly burdened and blamed. Allow it to be, acknowledge the feelings and the difficulty of them. The situation is not fair. The gains and pains are not evenly distributed and there are some uncomfortable truths that will have to be faced in making progress. Some of your team may feel that they’re being blamed for history or being asked to solve problems caused by earlier generations. Again, allow the feelings, talk about them, then use these feelings as invitations to become more fully informed.

Above all, we all need to allow ourselves to accept that there are many challenges ahead and that the way forward is not wholly clear. We may have to accept that, at least in part, we do not know the answer.

This then opens the way for Inquiring – the act of asking better questions can be in a catalyst for deeply radical change.

What is the lens we look through when we look at fairness? Do we have a sense of this being “a problem” or a confrontation about which we are defensive? Or is it mainly seen as an opportunity and a chance to seize new potential and new insight. Framings have consequences. So be very interested in the language and imagery you find yourself and others using. Always be curious about how we are approaching the question.

It is also worth being curious about intent and motivation. Ask, do we care? How much do we care? Why do we care? Perhaps be interested in whether your motivation (the organisational motivation) is for me, for us, for them. The nature of the intention and the source of the motivation will have implications for how your policies and practices emerge in practice. Be interested in the nature of the motivation, and of the statements and policies that flow from it. Be very interested in the consequences, and be prepared to ask “what if we come at this with a different angle?”. So much flows from the energy of the intention. If you are not getting the results you expect, be rigorously interested in the intention and what it might be doing.

You might also need to inquire deeply into data. What are we sure about? How are we so sure? Maybe you can find ways to involve others to get a richer view of what it is like for different people in your organisation? How can you find out what sort of people find your organisation so difficult that you don’t have them? How can you get better data, and keep your better data alive? It’s often useful to invite others to participate in this. Very often genuinely shared inquiry is a wonderful and powerful change in itself, but for this to be so the invitation must be a genuine one – people must be able to say no, and you must be willing for them to provide answers you’re not expecting!

Don’t expect everyone to move at the same pace on this. It’s ok for different people to have different energies. Be interested in who can be boldly experimental, bringing creative energy because they see this as a frontier. Who are these people and how can you invite them into your process? How can you best use their talents?

Where people are less enthusiastic, there’s no need for this to be a problem. Let success be your ally. But do pay attention to where people in leadership positions are using power to undermine others, and to block or sabotage progress. Then be really interested in why. How can you turn their opposition into a useful energy? Opposition is usually fear of a loss. In saying no, they are seeking to protect something they value. What is it? How can you invite them to divert this energy into work that protects what they value without blocking change?

You will also need to be continually learning, this is not a field in which anyone knows the answer. So being limitless in your curiosity and always open to learning is brilliant. Doing this with others – creating a culture of the team and organisation becoming continually wiser – is part of the success and is in itself a diversity and fairness intervention. The more that lesser heard voices are genuinely invited in and heard, the more the work is already being done.

As you do this work, do pay lots of attention to how you are doing it, both yourself and the wider organisation.

This is where meta-awareness comes in – paying attention to how you are thinking and acting while you are doing it; as well as paying attention to broader patterns at work in the system as a whole.

Meta-awareness is the capacity at times to step ever so slightly above the flow of your own experience in the moment. It is a perspective that allows you, for example, to see that you are thinking when you are thinking. Most often when we think we’re just lost in thought, unaware that we are thinking. With meta-awareness we see that we are thinking as the process is going on. That allows us to see our habitual thoughts and feelings simply as habitual thoughts and feelings. When we can do this, we are in a much better position to recognise the thoughts and feelings we habitually have about people who are other than us – the judgements and prejudices we all hold – as simply being a set of judgements and prejudices.

When we’re able to see these for what they are then it’s much easier to let go of them and to change them – if that is what is called for. Unconscious prejudices, which are intrinsic to the human condition, become much easier to manage when one has meta-awareness. It is not that meta-awareness in and of itself eliminate unconscious bias. Rather, it illuminates it – for oneself, from within – and that makes it much easier to manage and, in time, transform.

But meta-awareness in our use of the term is simply a quality of the individual. With Team Mindfulness, teams become more aware of themselves. That is a form of collective meta-awareness. Teams that cultivate that kind of awareness of themselves as teams are then in a position collectively to question their own collective attitudes and behaviours when it comes to Fairness. When teams begin to do that, organisations and the wider systems of which they are a part also begin to change.

A few closing words

There is no greater challenge before us. Our organisations need the richest skills, and to make the most of all our talents. This is the only way we will address the enormity of the global challenges we now face. Doing so with more colours on our palette, a stronger range of voices in our conversations, will be important in creating new ways of meeting the future. But above the utility of this, there is also the simple fact of fairness. It is simply right that we are fair. The insight of the Fairness Framework offers us a way of asking better questions about fairness and creating the conditions for a wider group of our fellow citizens to thrive in work. Using the AIM approach supports the sensitive and rigorous pursuit of that intention.

About the Authors

Chris Nichols is co-founder of the specialist systems change consulting firm GameShift, Over the past three decades he has worked in public service, consulting, finance and academia. His work brings creative provocation and spiritual practice to the boardroom in service of human and more than human flourishing.

Chris Nichols is co-founder of the specialist systems change consulting firm GameShift, Over the past three decades he has worked in public service, consulting, finance and academia. His work brings creative provocation and spiritual practice to the boardroom in service of human and more than human flourishing.

Philippa Hardman is co-founder with Chris Nichols of GameShift. She is a chartered accountant by background, with 25 years consulting experience including Coopers & Lybrand (now PwC) and PA Consulting. She was previously co-leader of the strategy engagement group and Director of Ashridge Consulting.

Michael Chaskalson is a Professor of Practice at Ashridge Executive Education at Hult International Business School and associate at The Møller Institute at Churchill College in the University of Cambridge. A pioneer in the application of mindfulness to leadership and in the workplace, he is founding Director of Mindfulness Works Ltd. and a partner at GameShift.