By Michael Chaskalson and Megan Reitz

Political and economic instability, climate change, globalisation, disruption, an unprecedented pace of change and overwhelming channels of communication – how can leaders stay focussed and make good decisions? Mindfulness can help. Research with a cohort of business leaders shows it enhances resilience, the capacity for collaboration and the ability to thrive in complex conditions – if they practice it regularly.

Leadership Today

There have never been times like this for organisational leaders. Whether we look at markets, systems, climate, politics or technology, unpredictable disruption is the new normal. On top of this, leaders are called on to manage a wider range of relational networks than ever before and the systems in which they function are deeply and unpredictably complex. Under these conditions they have to facilitate co-operation, idea generation and decision-making – across geographical boundaries and across differing viewpoints, both inside and outside their organisations – while somehow staying on top of vast flows of information from emails, messaging, calls and meetings. To cap all of that, they must also, by some means, maintain a healthy family and social life.

In this maelstrom, leaders have to focus on their multiple tasks in hand while continuing to relate and work well with others.

To lead well today, to thrive in situations where it’s not possible to engineer or control outcomes, you have first of all to manage your own attention and your own emotional responses.

Successful leadership today depends on three key leadership capacities.

1. The capacity to collaborate with others.

2. The capacity for resilience.

3.The capacity to survive and thrive in complex contexts.

There is a growing consensus amongst management thinkers1 around these capacities, but to date there’s been no agreement on how one can best help executives to develop and sustain them. There has, until now, been little by way of researched evidence around the best method for doing this.

Our own recent research2 tells us that systematic mindfulness training and practice may offer a response.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Mindful Leadership: Our Research

Mindfulness – a way of paying attention with care and discernment to yourself, others, and the world around you – has been extensively researched over the past decade. That has provided significant evidence (including compelling neuroscientific evidence) around its many benefits.3 But most of that evidence comes from clinical contexts and few studies have been conducted with business leaders.

The key questions are:

• Does systematic mindfulness training actually improve leadership capacities?

• If it does, how does it?

• And how much time and effort do you need to invest in order to achieve results?

To answer these questions, we conducted the world’s first study of a multisession mindful leader training programme that had a wait-list control group. This means that half of the participants received their training immediately while the other half received it later, but we measured key characteristics in both groups at the same times before and after the first group was trained. By comparing the two groups’ results, we were able to tell what the effect of the training really was.

Our data was drawn from 57 senior business leaders who attended three half-day workshops every two weeks as well as a full-day workshop and a final facilitated conference call. We guided them in mindfulness practices, shared current thinking around leadership and discussed the implications of mindfulness for leadership practice, and we asked them to do a daily home practice of mindfulness meditation and other exercises.

They undertook a customised mindful leadership 360-assessment before and completed a range of psychological inventories, measuring their levels of anxiety, their resilience, their capacities for empathy and so on. We also recorded our participants’ as they discussed in small group the difficulties they found with attempts to learn to be mindful throughout the process and we transcribed and analysed that information.

Our findings provide a valuable, robust, and realistic guide for leaders seeking to become more mindful.4

Does Mindfulness Training Develop Leaders?

It does – but it depends on how much they practice.

Mindfulness training does produce an improvement in three capacities that are key for successful leadership in the 21st century: resilience; the capacity for collaboration; and the ability to lead in complex conditions. But there’s a catch.

We found that by simply attending one or more of our workshops our participants’ resilience increased to some extent. Maybe that was because we shared some useful tools and techniques. And perhaps it was because resilience tended to be top of the list in terms of their personal objectives. But the other improvements our participants experienced depended on the amount of daily mindfulness practice they did. The more the better.

In our study, the leaders who undertook the formal meditation practices we set them, for at least 10 minutes every day, progressed significantly more than others who did not.

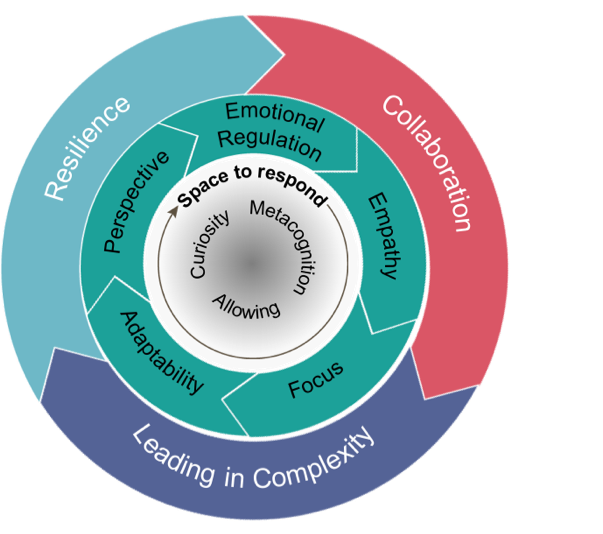

Exploring the mechanisms underlying the changes that the leaders on our program experienced, we found a hierarchy of effects. At its base, and underlying all the other positive impacts reported, were three meta-capacities.

• This is the ability to choose, at crucial times, to observe what you are thinking, feeling and sensing, in the moment. It is like stepping out of the fast flowing and sometimes turbulent stream of experiencing onto the bank, so you can notice what’s going on in your thoughts, feelings, sensations and impulses. This helps you to see your thoughts, feelings and so on as just that – thoughts and feelings. You don’t mistake them for fixed realities, which many of us often do.

The ability to see thoughts such as “This guy thinks I’m a real jerk” as just thoughts, and not as realities, frees us to adopt new perspectives on our experience.

Metacognition helps us to escape the unconscious, automatic pilot mode of the mind that often drives us through our daily tasks.

• Allowing. This refers to the ability to let what is the case, be the case. It’s about meeting your experience with a spirit of openness and kindness to yourself and others. It’s not about being passive or weak. Rather, it’s about facing up to what is actually going on from moment to moment with a spirit that is open-hearted and open-minded.

An allowing attitude frees us from the trap of unconscious and unhelpful prejudgement.

• Curiosity. This means taking a lively interest in what has shown up in our inner and outer worlds.

This helps us to bring our awareness into the present moment and stay with what we find there. An active curiosity is an effective counter to the default route of an automated response to what we encounter.

The leaders on our program told us that between them these three meta-capacities opened a small but crucial space in the previously automated flow of their experience. They noticed themselves becoming less reactive and more responsive.

This had a domino effect on many other “secondary” skills. It enabled them to better regulate their emotions, empathise with others, focus more readily on issues at hand, adapt to the situations they found themselves in, and take broader perspectives into account.

That is how mindfulness training impacts the important leadership capacities of resilience, collaboration and leading in complex conditions.

This is shown in the model below.

Mindfulness interventions, combined with regular mindfulness practice of ten minutes or more per day, develops the ability to lead in today’s tumultuous world.

How should this be trained?

There are real benefits to be had from introducing mindfulness into a leadership development programme but they don’t come from a single one-hour workshop or lecture. Here’s what we suggest to anyone wanting introduce mindfulness into their leadership development programmes:

• Start with yourself. Especially, try to develop a daily practice so you’ll get some sense of what that takes.

• Good teaching is crucial. We notice on our own trainings how easily people grasp the wrong end of many sticks when they first begin to practice mindfulness. Seek out a well-trained mindfulness instructor. The UK Network for Mindfulness Teacher Trainers has published guidelines that can help you to identify what a well-trained teacher might be like – although finding one who is also experienced in working in leadership contexts can be tricky.

• At work, a formal “taster session” can be a good way to gauge interest and build commitment to a programme. But it’s only ever a start. If you want the impacts reported in our research project, an extended mindfulness intervention that supports practice over a sustained period is called for.

• If possible, set aside a space for people to practice at work. This should be somewhere quiet and private.

• Encourage people to practice together if they want to. Maybe facilitate group-based audio-instruction guided meditation at a set time of the day.

•Start your meetings with a “mindful minute” or any similar process that helps those present to adjust the quality of their attention and focus on others in the meeting as well as the issue at hand.

We don’t underestimate how difficult it can sometimes be for leaders to fit a daily meditation practice into their busy schedules.

This is what we advise:

• First of all, work out when and where you will practice for at least ten minutes every day. What works for you? If your life allows for any degree of routine, try to set the same time and place for your meditation every day. Routine really helps.

• Find audio downloads of meditations that you enjoy. You can download free guidance from Michael at http://mbsr.co.uk/audio.php – select ten minute practices you enjoy.

• If you are comfortable doing this, tell those closest to you that you want to practice and ask for their support and encouragement.

• Might a friend or a work colleague also be interested in practising? Discussing your experiences and offering support and encouragement can help.

• As well as the ten minutes of formal practice, take moments in the day to pause and simply notice your thoughts, feelings and sensations in the present moment. Allow and accept what you notice. If it helps, plan these moments in your diary or build up a habit whereby you routinely associate a particular activity with becoming mindful. Some of our participants spoke about how they began to consciously “check in” with themselves just before they put the key in the door of their home when they arrived back from work.

• Practicing “informal” mindful walking, running, swimming and even showering are all useful and often enjoyable activities. Do them as well as the formal meditations rather than instead of them.

Mindfulness training will never in and of itself remove the enormous challenges that leaders face today. But it can significantly ease the task.

[/ms-protect-content]About the Authors

Michael Chaskalson (michael@mbsr.co.uk) is one of the pioneers of the application of mindfulness in leadership and in the workplace. He is the author of The Mindful Workplace (Wiley, 2011) and Mindfulness in Eight Weeks (Harper Thorsons, 2014). He is the CEO of Mindfulness Works Ltd., a mindfulness consultancy, and a Professor of Practice adjunct at Ashridge Business School.

Michael Chaskalson (michael@mbsr.co.uk) is one of the pioneers of the application of mindfulness in leadership and in the workplace. He is the author of The Mindful Workplace (Wiley, 2011) and Mindfulness in Eight Weeks (Harper Thorsons, 2014). He is the CEO of Mindfulness Works Ltd., a mindfulness consultancy, and a Professor of Practice adjunct at Ashridge Business School.

Megan Reitz (megan.reitz@ashridge.hult.edu) is Professor of Leadership and Dialogue at Ashridge Executive Education, Hult Business School. She is the author of Dialogue in Organizations (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015). Previously, she was a consultant with Deloitte; surfed the dot-com boom with boo.com; and worked in strategy consulting for The Kalchas Group, now the strategic arm of Computer Science Corporation.

Megan Reitz (megan.reitz@ashridge.hult.edu) is Professor of Leadership and Dialogue at Ashridge Executive Education, Hult Business School. She is the author of Dialogue in Organizations (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015). Previously, she was a consultant with Deloitte; surfed the dot-com boom with boo.com; and worked in strategy consulting for The Kalchas Group, now the strategic arm of Computer Science Corporation.

References

1. see for example Barton, D., Grant, A. and Horn, M., (2012). Leading in the 21st Century. McKinsey Quarterly, June, available from http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/leading_in_the_21st_century/leading_in_the_21st_century [accessed 5th January 2015]. See also Centre for Creative Leadership (2011), Future trends in leadership development: A white paper available from insights.ccl.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/futureTrends.pdf [accessed 10th May 2015].

2. https://www.ashridge.org.uk/faculty-research/research/current-research/research-projects/the-mindful-leader/

3. Chiesa A. and Serretti A. (2009), “Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis”, The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, Vol. 15 No. 5, pp. 593–600.

4. https://www.ashridge.org.uk/faculty-research/research/current-research/research-projects/the-mindful-leader/