By Will Baber and Arto Ojala

IT and software industries appear to be collaborative in projects in house and among organisations as they plan and negotiate for mutual benefit. How can skilled, aware negotiators better match up their thinking to avoid communication and process failures?

Collaboration is a fact of life throughout the IT industry especially in the development of large scale communication systems and software applications. Collaboration arises through successful negotiations that clarify the path for close work among employees, freelancers, outsourced services and other parties in completing projects and satisfying stakeholders.

The importance of negotiation to the well being of the IT industry led the authors to investigate the expectations and approaches that negotiators in this industry have in mind as they negotiate. The literature on the IT industry shows how important negotiation is, but has not looked into the thinking that might impact communication and the success or failure of a negotiation. To what extent is it possible for negotiators’ thinking about negotiation to match or conflict?

We chose to investigate negotiation thinking in two different cultures in order to help highlight differences and similarities and identify a range of styles. We can assume that practices of negotiation participants vary in different cultures because cultures are demonstrably different and because previous research has shown that negotiation styles are associated with cultures. Further, research on negotiation has shown that successful and smooth communication leads to better results for the parties.

The cultures we chose are geographically distant: Finland in Northern Europe and Japan in North East Asia. Finland and Japan differ in their philosophical backgrounds, one Protestant and Rationalist and the other steeped Confucian and Buddhist traditions. Additionally they have various differences described in the literature such as attitudes towards power, gender equality, and individualism.1 At the same time, the two countries have similarly aging populations, reputations for advanced use and implementation of technology, and high ethnic homogeneity.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]But how to look into what people are thinking? The study of Cognitive Psychology provides a way to do that. Humans think in terms of associations, categorisations and expectations.2 A cluster of such thoughts is referred to as a schema. People have schemata for things as well as processes. A schema for a thing like a table might be simple: the first thoughts to mind might include “flat top, legs, work, meals…”. A more complex schema may exist for an idea like “my parents’ kitchen table” which might include a flood of childhood memories. A simple process schema might be the script you expect when answering your phone during the work day: you check who is calling and answer in a familiar or formal way as appropriate. Negotiating a deal with a business partner is a more complicated process and numerous schemata are possible.

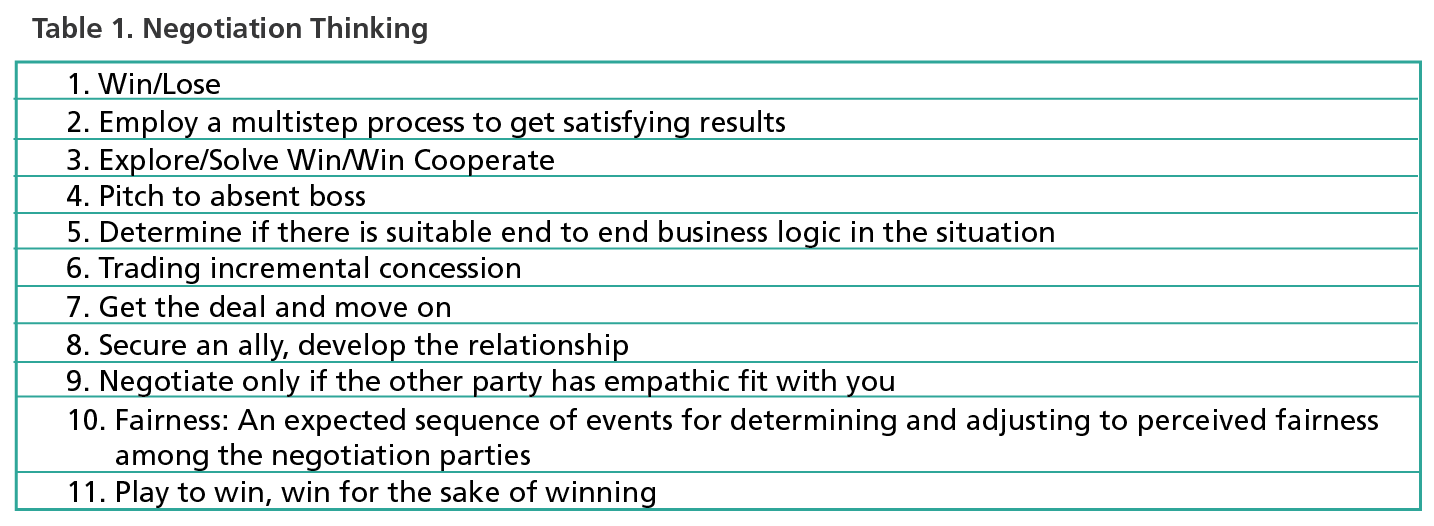

The complex of processes and expectations around creating a business agreement varies among people. To identify the possible schemata, we searched literature about negotiation and interviewed IT business managers. In the end we identified eleven schemata for negotiation from literature and interviews.3 Some are mutually exclusive, some can exist together, some are more about the start of the process or more about the final goals. (see Table 1 below)

Our survey targeted IT managers as those most likely to engage in some kind of negotiations and deal making. We asked their years of experience, their management level in the company, how frequently they are involved in negotiations, and the position they take in negotiations. The position refers to how they participate in negotiations, for example as team members, leaders, decision makers, or observers.

Some interesting findings came out of this survey. Remarkably, the two most competitive schemata, Win/Lose and Play to Win, were not selected even once by the survey participants. This result appears to confirm that in both cultures this industry leans towards collaboration and away from competitiveness.

Finnish and Japanese IT managers were also roughly in agreement about four schemata that they did mostly use. These common approaches include employing a multistep process to get satisfying results, making a pitch to a decision maker who was not present, determining end to end business logic, and exploring information to find win/win solutions.

The multistep process for satisfaction does not identify the specific process, but shows that these negotiators are interested in satisfying counterparties and stakeholders, rather than in making one sided gains. Negotiators of this sort are likely to take a thorough approach to communicating and discovering information.

The thinking behind comprehensive understanding of the business logic in a deal suggests caution about strategic alliances and how they add up over the long term. These negotiators seem to care about the position of their business and organisation in the broader value network. They may be very sensitive to relationships with other suppliers and clients beyond those parties represented at the negotiating table.

Exploring information for win/win patterns speaks for itself, these negotiators are not employing quick hacks to gain value. Their willingness to explore information also suggests flexibility and opportunism that may help to complete deals.

The fourth commonly selected schema, pitching to a superior who is not in the conversation, shows sensitivity to how decisions are made and how the final decision makers must be addressed and handled.

In addition to the four approaches mentioned above, about half of the managers from each background preferred to show fairness in the process of negotiation. Fairness is a culturally inflected practice, what is fair in one place, may not seem fair to other people. These negotiators should communicate not only that they want to show fairness, they should also discuss how to show it. In the end, the survey identified much common thinking among negotiators from these backgrounds to support cooperation and communication.

Two schemata were very common among Finns but absent or almost absent among the Japanese. No Japanese participants chose trading incremental concessions, or quid pro quo, whereas more than half the Finns chose this. Even if not all Finns chose it as a business negotiation approach, perhaps most Europeans would recognise this as a default bargaining behaviour, incremental compromise. Similarly lopsided was the choice of getting the deal and moving on which almost half the Finns seemed to like but only one Japanese negotiator selected.

It seems from the research that there is a lot of potential for thinking to match up in this industry even across distant borders, but also some for opportunities for mismatch. Having some idea about which approaches might or might not be in play, business negotiators can look carefully when interacting to see if they are on the same page or not. Similar thinking does not mean it will be recognised automatically by all sides. Negotiators must discuss and look for signals from counterparts in order to react appropriately.

But what kind of negotiators seem to have the most flexibility and the most tools at hand? The research suggests that it is not age that makes a broadly skilled negotiator. Instead the individual’s rank in the workplace correlates mildly with an increased number of schemata. Additionally, the frequency with which a person engages in negotiation correlates somewhat with having more schemata at hand. However the strongest connection appears between schemata and a person’s position in negotiation; team leaders and final decision makers have more schemata available to them than team members or support staff. It may be that practice and decision making authority build up choices or that those with more choices available to them rise higher in decision making position.

In this day and age, technology dominates the issues of business management but IT business people must constantly refine and develop their person to person skills for interacting, communicating and negotiating. Identifying and using approaches that allow better communication and interaction with the existing and potential partners may lead to better outcomes, greater satisfaction in deal making, and lower transaction cost in the long term as successes lead to new beneficial deals. The IT communities investigated here show a fairly sophisticated, though not always overlapping comprehension of how to build value and alliances and work together. Smart managers in the IT world will seek to understand their own thinking and that of their counterparts.

For more detail, see the authors’ academic writing on this topic: Baber, W. W., & Ojala, A. (2015). Cognitive Negotiation Schemata in the IT Industries of Japan and Finland. Journal of International Technology and Information Management, 24(3), 6.

[/ms-protect-content]About the Authors

Will Baber has combined education with business throughout his career. His work has included economic development in the State of Maryland, language services in the Washington, DC area, supporting business starters in Japan, and teaching business students in Japan and Europe. Currently he is at Kyoto University teaching and researching negotiation and other topics as an Associate Professor in the Graduate School of Management. He is lead author of the 2015 textbook Practical Business Negotiation.

Will Baber has combined education with business throughout his career. His work has included economic development in the State of Maryland, language services in the Washington, DC area, supporting business starters in Japan, and teaching business students in Japan and Europe. Currently he is at Kyoto University teaching and researching negotiation and other topics as an Associate Professor in the Graduate School of Management. He is lead author of the 2015 textbook Practical Business Negotiation.

Arto Ojala is working as a University Lecturer in the Department of Computer Science and Information Systems at the University ofJyväskylä, Finland. He is also Adjunct Professor in Software Business at the Tampere University of Technology. His articles have been published in Information Systems Journal, Journal of Systems and Software, IEEE Software, IT Professional among others. Ojala has a PhD in economics from the University of Jyväskylä.

Arto Ojala is working as a University Lecturer in the Department of Computer Science and Information Systems at the University ofJyväskylä, Finland. He is also Adjunct Professor in Software Business at the Tampere University of Technology. His articles have been published in Information Systems Journal, Journal of Systems and Software, IEEE Software, IT Professional among others. Ojala has a PhD in economics from the University of Jyväskylä.

References

1. G. Hofstede, J. G. Hofstede, and M. Minkov, Cultures and Organizations: Software of the mind, 2nd ed. New York , NY: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

2. M. Kamppinen, “The Cognitive Schema,” in Consciousness, Cognitive Schemata, and Relativism: Multidisciplinary Explorations in Cognitive Science, M. Kamppinen, Ed. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 1993, pp. 143–162.

3. W. W. Baber and A. Ojala, “Cognitive Negotiation Schemata in the IT Industries of Japan and Finland,” J. Int. Technol. Inf. Manag., vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 87–104, 2015.