By Simon L. Dolan and Kyle M. Brykman

Introduction

Resilience is an emerging concept in business and psychology. Its origins are in the school of thought inspired by Seligman and colleagues and the positive psychology movement.1 The premise of positive psychology is that well-being can be defined, measured, and taught. Well-being includes positive emotions, intense engagement, good relationships, meaning, and accomplishment (PERMA). Questionnaires can measure it. Trainers can teach it. Achieving it not only makes people more fulfilled but makes corporations more productive, soldiers more resilient, students more engaged, marriages happier. Seligman even came up with a formula:

H = S + C + V

Happiness (H) equals your genetic set point (S) plus the circumstances of your life , plus factors under voluntary control (V). Unlike previous promises of happiness, positive psychology insists it is evidenced-based, using the resources of contemporary social science—surveys, longitudinal studies, meta-analyses, animal experiments, brain imaging, hormone measuring, and case studies. Most recently, Seligman has turned to big data analyses of postings on social media websites (e.g., Facebook). He and his team have created a curriculum of positivity. They have measured the impact of training and the surprising benefits of learned optimism. The conclusions of positive psychology can validate experience and offer hope, in a sense, that:

- Genetics shape mood and personality, but only in part.

- Human beings can change and improve.

- Moods matter but can be altered by understanding circadian rhythm.

- Individuals have signature strengths that can be identified and employed.

- Flow moments exist and can be cultivated.

- Other people matter.

- Strong social bonds are crucial.

- Marriage and religion contribute to well-being.

- Positivity improves health, work, creativity, and relationships.

- Intrinsic adaptation to both the good and

bad is useful - Optimism is a learned skill.

- Happiness requires effort.

- Happiness is contagious.

And within the stream of research in positive psychology, there is the emerging construct of Resilience, that for many represent the opposite pole of stress – the focus is on positive adjustment to inherent life challenges, resulting in a healthy, productive, and happy self. Although the construct of resilience has been around for decades, it gathered steam and popularity during and post the COVID-19 pandemic. Resilience, though often applied to individuals, is also relevant to teams, companies, communities, and governments. During the pandemic, organizational resilience was tested, as companies encountered unexpected challenges that necessitated constructive adaptation (structure, processes, contacts with employees, and market creation and penetration). The rules of the games have changed and those who were unable to bounce back (i.e. demonstrate resilience), for whatever reason, were unfortunately wiped out from the business scene. The non-resilient attitude of these companies let to their demise, to their extinction.

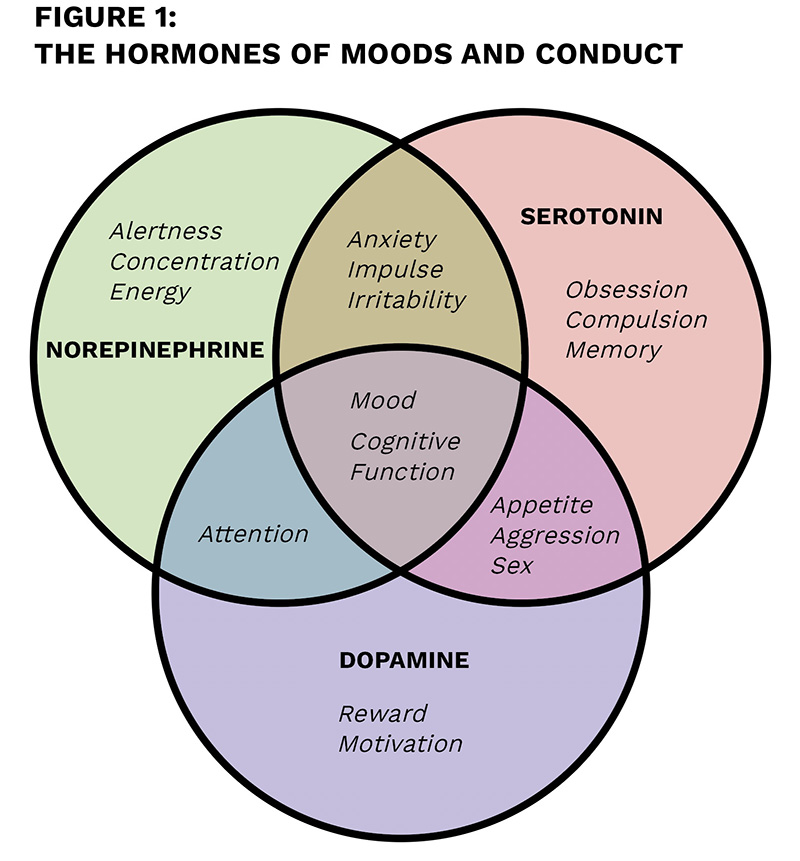

In this paper we focus on the essence of individual resilience, and more specifically approached from the angle of neuroscience. Our aim is to advance the proposition that some hormones are playing an important role in creating a sustainable resilience. More specifically, neurotransmitters, like dopamine, seem to help spark the chemical messengers that keep us alert and on task. Dopamine in particular, seem to have a biological connection to motivation, focus and resilience.2

The word resilience derives from the present participle of the Latin verb resilire, meaning “to jump back” or “to recoil.” The base of resilire is salire, a verb meaning “to leap” that also pops up in the etymologies of such sprightly words as sally and somersault. In more clinical terms, resilience is the ability to adapt to difficult situations. When stress builds, or adversity and trauma strikes, you still experience anger, grief, anxiety, and pain, but you are able to keep functioning, sometimes even flourishing because of it.3 The Mayo clinic offers the following tips for becoming more resilient:

Get connected

Building strong, positive relationships with loved ones and friends can provide you with needed support and acceptance in good and bad times. Establish other important connections by volunteering or joining a faith or spiritual community.

Make every day meaningful

Do something that gives you a sense of accomplishment and purpose every day. Set goals to help you look toward the future with meaning.

Learn from experience

Think of how you’ve coped with hardships in the past. Consider the skills and strategies that helped you through difficult times. You might even write about past experiences in a journal to help you identify positive and negative behavior patterns — and guide your future behavior.

Remain hopeful

You can’t change the past, but you can always look toward the future. Accepting and even anticipating change makes it easier to adapt and view new challenges with less anxiety.

Take care of yourself

Tend to your own needs and feelings. Participate in activities and hobbies you enjoy. Include physical activity in your daily routine. Get plenty of sleep. Eat a healthy diet. Practice stress management and relaxation techniques, such as yoga, meditation, guided imagery, deep breathing or prayer.

Be proactive

Don’t ignore your problems. Instead, figure out what needs to be done, make a plan, and take action. Although it can take time to recover from a major setback, traumatic event or loss, know that your situation can improve if you work at it.

The concept of resilience at life and at work

Resilience can be conceived in several ways, including as a stable trait-like difference, a capacity, an outcome, and a process. The trait perspective assumes that some people are inherently more resilient due to their inherent personality, including greater hope and optimistic beliefs. The capacity perspective focuses on the resources that people (e.g., social support) and organizations (e.g., psychologically safe culture) have acquired that enable them to bounce back quickly and more effectively. The outcome perspective focuses on whether individuals demonstrate resilience, in terms of achieving greater performance, cohesion, and/or well-being despite adversities. It focuses on whether one is resilient based on their actions, whereas the capacity perspective considers whether one can demonstrate resilience if and when adversity strikes. Finally, the process perspective captures a combination of these elements, as it focuses on how entities use their capacities to demonstrate resilience.

Common throughout these perspectives is that resilience involves two defining elements – the experience of adversity and positive adaptation despite this adversity.4 First, entities must experience adversity to demonstrate and build resilience. Adversity ranges on many continuums, including severity, duration, and predictability, which impacts individuals’ and organizations’ ability to demonstrate resilience. For example, consider the different behaviors and emotions involved in responding to a severe and unpredictable acute event (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic) versus a minor and predictable chronic obstacle (e.g., high work demands). What matters, however, is how people perceive the adversity. Resilient people and organizations view adversity as a springboard for growth and development as opposed to a negative experience that should be avoided at all costs.

Second, resilience involves demonstrating positive adaptation, such that an individual or organization returns to (bounces back), or even surpasses (thrives), previous levels of functioning.5 Positive adaptation may happen instantaneously or take many months to years. It is facilitated by mechanisms of social support, learning, communication, and improvisation, among others. Without positive adjustment, the entity simply succumbs to the adversity or may survive, but with some impairments, and thus did not demonstrate a resilient outcome.

The key role of Dopamine and its connection to resilience

Now, that we understand what resilience entails, we turn to the latest discoveries from neuroscience that explains why some people are more resilient than others. The field of neuroscience places the focus on the role of Dopamine. Dopamine is known as the pleasure-and-reward neurotransmitter. It helps create a feeling of enjoyment and a sense of reward and accomplishment when we get something done. It motivates performance and builds positive habits.

Research undertaken at the Huberman Lab at Stanford University, proposes that Dopamine, in its role as chemical messenger in our brain, has the ability to help us create, stay focused, and complete projects with extreme efficiency.6 Huberman has concluded that Dopamine helps us feel more motivated, energized, happy, alert, and in control. It so follows that Dopamine would fuel resilience by stimulating support seeking, persistence over challenges, and positive mood to execute activities. In a series of videos on Apple Podcasts, which reviews the research on Dopamine consequences, Dr. Huberman and his colleagues presents 14 tools to show how to control dopamine release to increase motivation and focus and reduce addiction and depression. They also explain why dopamine stacking with chemicals and behaviors inevitably leads to states of underwhelm and poor performance. They further explore how to achieve sustained increases in baseline dopamine, compounds that protect dopamine neurons (e.g., caffeine) from specific sources. Finally, they describe non-prescription supplements for increasing dopamine—both their benefits and risks—and synergy of pro-dopamine supplements with those that increase acetylcholine.7

In other words, more and more evidence is showing that we tend to repeat behaviors that cause dopamine to be released. On the flip side, low dopamine correlates with feelings of hopelessness, worthlessness and even depression.8 Perhaps the bad news, then, is that Dopamine can also play a role in addictive behaviors. Dopamine deficiency can impair our ability to manage stress, focus attention, finish tasks, and maintain motivation.9 Other downsides including self-isolation and self-destructive thoughts and behaviors. Researchers have found that, in the long-term, low dopamine levels, or poor dopamine signaling can, result in hand tremors, slowness of movement and even pre-Parkinson’s symptoms.10

How Dopamine Works in the Brain

Dopamine begins kicking in before we obtain rewards. This is important because it means that its real job is to encourage us to act, either to achieve something good or to avoid something bad. Essentially, dopamine affects how our brain decides whether a goal is worth the effort in the first place. When our brain recognizes that something important is about to happen, dopamine kicks in. Researchers have found that dopamine spikes occur during moments of high stress — like when soldiers with PTSD hear gunfire.

Researchers from Vanderbilt University headed by postdoctoral student Michael Treadway and Professor of Psychology David Zald, correlated dopamine levels with resilience by mapping the brains of “go-getters” and “slackers.” They found that people willing to work hard had higher dopamine levels in the striatum and prefrontal cortex — two areas known to impact motivation and reward. Among slackers, dopamine was present in the anterior insula, an area of the brain involved in emotion and risk perception.11

Similar research from Brown University assessed the role of dopamine in influencing how the brain evaluates whether a mental task is worth the effort by measuring natural dopamine levels while choosing between memory tasks of varying difficulties. More difficult mental tasks were rewarded with more money, and those with higher dopamine levels in a region of the striatum called the caudate nucleus were more likely to focus on the benefits (the money) and choose the difficult mental tasks. Those with lower dopamine levels were more sensitive to the perceived cost, or task difficulty.12 Next, the participants completed experiments after taking either an inactive placebo, methylphenidate (a stimulant drug typically used to treat ADHD), or sulpiride (an antipsychotic medication that, at low doses, increases dopamine levels). Increasing dopamine boosted how willing people with low, but not high, dopamine synthesis capacity were to choose more difficult mental tasks.

In sum, the results from these experiments reflected the findings for natural varying dopamine levels. To gain more insight into the decision-making process, the researchers tracked the participant’s eye movement as they reviewed information about task difficulty and the amount of money they would receive. Their gaze patterns suggested that dopamine didn’t alter their attention to benefits vs costs. Rather, it increased how much weight people gave to the benefits once they were looking at them.

How Dopamine Makes You Feel

Dopamine, thus, seems to help us know exactly what we want and how to get it: it helps us access our self-confidence, rational, self-awareness, and our critical thinking. Dopamine also helps us focus intently on the task at hand and take pride in achievement: it enhances our strategic thinking, masterminding, inventing, problem solving, envisioning, and pragmatism. We may feel overly alert or need less sleep than other people. Dopamine also seems to support the following activities:

- Reward and pleasure centers.

- Attention and learning.

- Sleep and overall mood.

- Behavior and cognition.

- Movement and emotional responses.

- Voluntary movement, motivation, and reward.

And here is another interesting angle. It seems that Dopamine also plays an important part in morning wakefulness. Sergio Gonzales and his collaborators report that dopamine inhibits norepinephrine’s melatonin producing effects and shuts off melatonin production in the morning when the brain needs to awaken.13

Implications

Some research assert that excessive dopamine can lead to excessive risk-taking behaviors and impulsive actions, like reckless driving, shoplifting, violence, or over-control of others. However, as a person’s neurobiology, brain structure, and genetics will also influence symptoms, two people could have equally high levels of dopamine, but entirely different symptoms may result. This could be due to differences in dopaminergic receptors and how each brain processes the dopamine. Below is a list of some negative symptoms that could stem from high dopamine.

Agitation

Those with high dopamine may feel internally restless and overstimulated. While sufficient dopamine can actually help some people stay calm, abnormally high levels can make a person feel internally nervous and knotted. It may be difficult to sit still for long periods of time.

Anxiety

Some people may feel more anxious when dopamine levels increase in certain parts of the brain. This may be due to dopaminergic receptor dysfunction as well as the specific areas of the brain that experience the dopamine elevations. This is generally why some people with anxiety disorders feel more anxious with dopamine reuptake inhibitors (DRIs).

Cognitive acuity

People call amphetamines “speed” for a reason – it makes their cognition speed up and their mental performance improves. It seems like other people are functioning in slow-motion whereas the user is locked in a state of peak performance. Heightened levels of dopamine are associated with improvements in cognitive function such as memory, learning, and problem solving.

Hyperactivity

Some people become hyperactive (not to be confused with inattentive) when they have high levels of dopamine. The hyperactivity may be a byproduct of constant pleasure-seeking behavior associated with dopamine elevations. High dopamine for some people makes it difficult to sit still (counterintuitive to most ADHD diagnoses).

Insomnia

Excess dopamine may make it difficult to fall asleep, thus resulting in insomnia. Low levels of dopamine are associated with lethargy and chronic fatigue. Drugs that increase dopamine levels in the brain are associated with sleeping problems and insomnia.

Mania

Those experiencing mania or hypomania may be partially fueled by elevations in dopamine. Mania is characterized by decreased need for sleep, feelings of happiness, talkativeness, social behavior, impulse behavior (e.g. shopping sprees), etc. Hypomania is considered a slightly milder version of mania. Both conditions may worsen or become triggered with increases in dopamine.

Paranoia

Those experiencing paranoia tend to have heightened levels of extracellular dopamine in the brain. Those with conditions like paranoid schizophrenia and paranoid personality disorder tend to also have problems with the number of dopaminergic receptors. The paranoia can often be mitigated with drugs that decrease dopamine. Even those without psychiatric conditions can experience paranoia as a byproduct of using certain drugs for the dopamine boost.

Stress and Burnout

Those who experience high levels of stress, such as those associated with a nervous breakdown, may experience boosted dopamine production. This dopamine is produced by the sympathetic nervous system that senses “danger.” Dopamine also initiates the production of adrenaline, leading you to feel extremely alert and less relaxed. Excess stress however is associated with depletion of dopamine or a “burn out.”

Source:High Dopamine Levels: Symptoms & Adverse Reactions, Mental Health Daily

(https://mentalhealthdaily.com/2015/04/01/high-dopamine-levels-symptoms-adverse-reactions/)

To the same extent that excess of Dopamine can trigger in some people adverse effects, a dopamine deficiency may present as mental challenges like distractibility, lack of follow-through, memory loss or forgetfulness, poor abstract thinking, slow processing speed. Attention issues, like ADD/ADHD, decreased alertness, failure to finish tasks, hyperactivity, impulsive behavior and poor concentration.

A dopamine deficiency can also contribute to physical issues like low energy, fatigue, sluggishness anemia, balance problems, blood sugar instability, carbohydrate cravings, decreased strength, or digestion or thyroid problems. Dopamine deficiency can present as emotional challenges like anger, aggression, hopelessness, worthlessness, guilt, depression, pleasure-seeking behavior, stress intolerance, social isolation, mood swings, procrastination, self-destructive thoughts.14

Depleted dopamine can result in a variety of issue in various systems in the body. Early warning signs are loss of energy, fatigue, sluggishness, memory loss, or depression. Other early symptoms include:

- Hard time self-motivating

- Cravings for chocolate

- Easily distracted

- Shiny object syndrome (easily distracted)

- Not feeling fulfilled when you accomplish a task

- Looking for quick fixes

- Addictive tendencies (Alcohol, drugs, work, exercise, emotional eating, social media, gambling, shopping)

- Having a hard time focusing and staying on task

- Self-sabotage

- Self-isolation

- Feelings of hopelessness or worthlessness

- Feeling tired in the morning

- Having a shorter temper than usual

- Don’t feel like going out but feel good when you do

Can we manage the Dopamine secretion in order to enhance resilience and avoid adverse effects?

In a 2013 article, researchers at Xiamen University, China, reported, “Most studies, as well as clinically applied experience, have indicated that various essential oils, such as lavender, lemon and bergamot can help to relieve stress, anxiety, depression and other mood disorders. Most notably, inhalation of essential oils can communicate signals to the olfactory system and stimulate the brain to exert neurotransmitters (e.g. serotonin and dopamine) thereby further regulating mood.”

Inhaling the appropriate essential oils can communicate signals to the olfactory system and stimulate the brain to release neurotransmitters that help regulate your mood. For example, research explained in an article in Current Drug Targets entitled “Aromatherapy and the Central Nerve System (CNS)” found that smelling bergamot, lavender, and lemon essential oils help to trigger your brain to release serotonin and dopamine.15

According to Jodi Cohen, essential oils help balance the dopaminergic system and it include immune modulating essential oils such as oregano, thyme, lavender, rosemary, and lemon. In an article labelled “How to Increase Dopamine with Essential Oils”, the authors provide the following explanation:

- Lavender oil seems to promote relaxation and peace. Low dopamine levels cause problems like poor sleep, anxiety and fatigue. Inhaling the calming powdery & flowery scent of lavender oil every day assists in promoting better sleep and decreases anxiety.

- Lemon Oil seems to boost “feel good” hormones in the body. Some, albeit limited research , suggests that lemon oil has powerful anti-depressant properties that helps beat the blues!

- Rose Oil seems to be a n anti-depressant and anti-anxiety effects. Some suggest that it also prompts psychological relaxation and improves sexual dysfunction

- Peppermint Oil seems to have a high menthol concentration which helps sometimes relieves high stress levels, agitation and dull moods

Source: https://superfoodsanctuary.com/how-to-increase-dopamine-with-essential-oils/

All in all, Jodi Cohen asserts that “these remedies must be able to cross the blood-brain barrier to modify the brain’s neurotransmitter response. Neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin lack the necessary transport mechanisms to cross the blood-brain barrier, while lipid-soluble essential oil molecules do not”.

Stress, Nutrition and Dopamine Output

When we experience stress, our body activates “fight or flight” chemicals known as adrenaline and noradrenaline that are part of the catecholamine group.16 These chemicals are derived from dopamine – hence the latter is a precursor to make the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and epinephrine. This means that when we are stressed out, we break down dopamine to produce stress hormones like oxytocin. Over time, multiple episodes of high stress can deplete dopamine reserves. According to Jodi Cohen, this happens when dopamine secreting cells get overwhelmed with stimulus to produce dopamine and begin to shut down, effectively reducing our ability to produce stress hormones on demand.17 This helps to explain how chronic and acute adversities might interact to affect or resilience responses. An individual who is experiencing a lot of chronic stress (e.g., difficult job responsibilities, work-family conflict) may be more susceptible to succumb to an unexpected adverse event, like the COVID-19 pandemic, relative to individuals who entered the situation while experiencing moderate or low levels of stress. It also speaks to the importance of proactively addressing our stressors, either through therapy, regular breaks, or job crafting, before they bubble up and overwhelm or incapacitate our stress response system.

In order to produce dopamine, we need to both consume adequate amounts of protein in our diet and good stomach acid and digestive function to supply our body with the building blocks it needs to make dopamine. When we consume (and properly digest) dietary protein, it is broken down into amino acids. Dopamine is made from the amino acid tyrosine, which converts into dopamine through a series of biochemical steps. Most supplements that claim to boost dopamine production within the brain often contain the amino acid tyrosine, which first converts to L-dopa before converting into the actual neurotransmitter. The conversion between tyrosine and dopamine is important, because without the dopamine neurotransmitter, an individual is more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease and will have a harder time finding life rewarding.18

Conclusion

Resilience is not a trait that you are either born with or without. It’s a set of behaviors, thoughts, and actions that can be learned and developed. When you break it down to the physical level in your brain, resilience is a neuroplastic process. It’s really about how well your brain handles the unexpected aspects that life brings.

Being resilient doesn’t mean that you don’t experience hard times. In fact, intense emotional pain, extreme trauma, and severe adversity are common in people who are considered very resilient. The road to resilience most often involves considerable hardship. That’s how we often build and demonstrate our resilience.

According to Richard Davidson in his book, The Emotional Life of Your Brain, resilience is one dimension of your emotional style and includes greater activation in the left prefrontal cortex (PFC) of the brain. Davidson writes: “The amount of activation in the left prefrontal region of a resilient person can be thirty times that in someone who is not resilient.”

Davidson’s early research found that the abundance of signals back and forth from the PFC to the amygdala determines how quickly the brain recovers from being upset. The amygdala is your brain’s threat detector responsible for the fight-or-flight response. More activity in the left PFC shortens the period of amygdala activation. Less activation in certain zones of the PFC resulted in longer amygdala activity after an experience producing negative emotions. Basically, some people’s brains weren’t good at turning off negative emotion once it was turned on.

In later research with the help of MRIs, Davidson confirmed that the whiter matter (axons connecting neurons) lying between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, the more resilient a person was. The converse was also true. Less white matter equates with less resilience. By turning down the amygdala, the PFC is able to quiet signals associated with negative emotions. The brain can then plan and act effectively.

Resilience means an adaptation in the face of adversity and the ability to bounce back from these circumstances without being overly influenced by negative emotions. Dopamine seems to be a neurotransmitter that enables the bouncing back rapidly and productively. Most people display a degree of resilience (and mobilization of the dopamine neurotransmitter) but recurrent episodes of stressful life and work events can deplete our dopamine reserves, making us less resilient.

Healthy nutrition and lifestyle can increase dopamine in the brain. Working up a sweat by running, swimming, dancing, or other forms of movement, can help by increasing dopamine levels in the body. Studies carried out on animals have shown that certain portions of the brain are flushed with dopamine during physical activity. When we are constantly exposed to stressors like financial difficulty, relationship troubles, workplace stress, and more, it affects our body’s production of dopamine, thereby reduces resilience.

And attitudes count. Resilient people seem to have this set of attitudes in common:

- They remain optimistic, but balance optimism with realism.

- They face, rather than ignore, their fears.

- They have a strong sense of right and wrong that provides an attitudinal framework.

- They partake in a religious or spiritual practice or are part of some other group with strong beliefs.

- They have a strong social support system in which they give to and receive from others.

- They have resilient role models to emulate.

- They make physical fitness a priority.

- They keep their minds fit by engaging in lifelong learning.

- They stay mentally flexible and have a good sense of humor.

- They have a calling, mission, or purpose in life.

About the Authors

Simon L. Dolan (Ph.D – University of Minnesota) is the president of the Global Future of Work Foundation and Honorary president of ZINQUO. He is a prolific writer and researcher, with over 77 books published (in multiple languages), over 150 articles in scientific journals, and over 600 conferences delivered throughout the world. He has been a professor at some of the leading business schools (ESADE, McGill, Boston – to name a few). He is a very solicited international speaker hence he speaks 7 languages. For more information visit his web site: www.simondolan.com.

Email: simon@globalfutureofwork.com

Kyle M. Brykman (Ph.D. -Queen’s University) is an Assistant Professor at the Odette School of Business, University of Windsor. His research focuses on employee voice, team resilience and conflict. His research has been featured in various prestigious academic journals, including the Journal of Organizational Behavior, Small Group Research, and Group & Organization Management. For more information visit his web site: kylebrykman.com.

Email: kbrykman@uwindsor.ca

Notes and References

- Dr. Seligman’s books have been translated into more than 45 languages and have been best sellers both in America and abroad. Among his better-known works are Flourish (Free Press, 2011), Authentic Happiness (Free Press, 2002), Learned Optimism (Knopf, 1991), What You Can Change & What You Can’t (Knopf, 1993), The Optimistic Child (Houghton Mifflin, 1995), Helplessness (Freeman, 1975, 1993) and Abnormal Psychology (Norton, 1982, 1988, 1995, with David Rosenhan).

- The overall structure of the paper was inspired by an excellent article published by Jodi Cohen, and entitled: Enhancing Dopamine for Resilience .While her angle is aromatherapy, the structure and some of her ideas were retained, cited and incorporated in this paper. The authors have invited Jodi to join them in preparing this paper but it has been turned down for her busy schedule. We wish to thank her for the reflections which were very instrumental to completing this paper. (https://vibrantblueoils.com/enhancing-dopamine-for-resilience/)

- Definition offered by the Mayo Clinic – https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/resilience-training/in-depth/resilience/art-20046311

- Hartmann, S., Weiss, M., Newman, A., & Hoegl, M. (2020). Resilience in the workplace: A multilevel review and synthesis. Applied Psychology, 69(3), 913-959. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12191

- Authors: Charles S. Carver, C. S. (1998). Resilience and thriving: Issues, models, and linkages. Journal of Social Issues, 54(2), 245-266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1998.tb01217.x

- Huberman Lab : Controlling Your Dopamine For Motivation, Focus & Satisfaction | Episode 39 https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/controlling-your-dopamine-for-motivation-focus-satisfaction/id1545953110?i=1000536717492

- Watch: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/controlling-your-dopamine-for-motivation-focus-satisfaction/id1545953110?i=1000536717492 .

- See: DOPAMINE DEFICIENCY, DEPRESSION AND MENTAL HEALTH https://bebrainfit.com/dopamine-deficiency/#:~:text=Low%20Dopamine%3A%20An%20Unexpected%20Cause%20of%20Depression.%20No,the%20underlying%20cause%20of%20depression%20in%20many%20cases.

- R A Bressan , J A Crippa The role of dopamine in reward and pleasure behaviour–review of data from preclinical research, PMID: 15877719 DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00540. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15877719/)

- Mark S. Gold, MD, Kenneth Blum, PhD, Marlene Oscar-Berman, PhD, and Eric R. Braverman, MD Low Dopamine Function in Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Should Genotyping Signify Early Diagnosis in Children? Postgrad Med. 2014 Jan; 126(1): 153–177. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2014.01.2735 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4074363/

- Source> David Salisbury, Slacker or go-getter? May 1, 2012 https://news.vanderbilt.edu/2012/05/01/dopamine-impacts-your-willingness-to-work/

- A Westbrook, R van den Bosch , I Määttä , L Hofmans , D Papadopetraki , R Cools, M J Frank Dopamine promotes cognitive effort by biasing the benefits versus costs of cognitive work, Science

2020 Mar 20;367(6484):1362-1366. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz5891. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32193325/ - Sergio González , David Moreno-Delgado, Estefanía Moreno, Kamil Pérez-Capote, Rafael Franco, Josefa Mallol, Antoni Cortés, Vicent Casadó, Carme Lluís, Jordi Ortiz, Sergi Ferré, Enric Canela, Peter J McCormick, PLoS Biol

2012;10(6):e1001347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001347. Epub 2012 Jun 19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22723743/ - OGonzales et al , op. cit.

- Xiao Nan Lv 1, Zhu Jun Liu, Huan Jing Zhang, Chi Meng Tzeng Aromatherapy and the central nerve system (CNS): therapeutic mechanism and its associated genes, Curr Drug Targets

2013 Jul;14(8):872-9. doi: 10.2174/1389450111314080007. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23531112/#:~:text=In%20the%20current%20study%2C%20the%20effectiveness%20of%20aromatherapy,key%20molecular%20elements%20of%20aromatherapy%20are%20also%20proposed. - See: Simon Dolan Stress, Self-Esteem, Health and Work. Palgrave -MacMillan 2007: Simon L. Dolan and Salvador Garcia, Covid-19: Stress, Self-Esteem and Psychological Well-being: How to assess risks of becoming depressed, anxious, or suicide prone? The European Business Review, May 13, 2020

- Jodi Cohen 3 Ways to Re-Wire Your Brain to Reduce Stress. https://vibrantblueoils.com/3-ways-to-re-wire-your-brain-to-reduce-stress/

- Brandon May What is the Connection Between Tyrosine and Dopamine? https://www.wise-geek.com/what-is-the-connection-between-tyrosine-and-dopamine.htm#:~:text=Dopamine%2C%20which%20activates%20feel-good%20hormones%20that%20process%20rewards,and%20dairy%20products.%20Dopamine%20is%20derived%20from%20tyrosine.

Disclaimer: This article contains sponsored marketing content. It is intended for promotional purposes and should not be considered as an endorsement or recommendation by our website. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and exercise their own judgment before making any decisions based on the information provided in this article.