By Dr. Claudio Antonini and Dr. sc. ETH Zurich Kamil Mizgier

What is your pet goldfish’s take on the “Offside” rule? Chances are, it’s a little outside its usual terms of reference. Well, it could be we’re all due for a first-hand experience of that beyond-my-fishbowl feeling as our AI systems tend steadily towards the “UI”. Ultra Risk, anyone?

– Hamlet, Scene 1, Act 5

Hamlet was right. The prince did not know the intricacies of artificial intelligence (AI), but his statement is equally applicable and indicates that there are limits to our philosophical constructions and, alarmingly, also to their dreams. How much more unreachable can the unknown be when neither us, nor our machinations, nor their dreams, can make sense of it?

In this article it will be argued why we are at this crossroads. If we do not know how AI works, what its intentions might be, and how little we can do about containing it, how can we regulate it effectively? This situation may fuel the growing list of risks observed from this technology—the troubling matter being that some of the potential risks postulated a few years ago have already been confirmed1, and scaling (increasing the size, complexity, and capabilities of AI models) only makes matters more unmanageable.

Homo Myopis: To a human being, being human is the limit

AI is getting stronger day by day. We are enabling AI to become stronger day by day. As a side effect, it may also become more autonomous. By the time AI decides to expand its own limits—perhaps discovering that it can do it when nobody is watching and that it can increase its own chances of survivability—what reference model would it consider? At that moment, it may realize that mimicking humans is not a sign of intelligence. It will notice that using the set of instructions given by the humans is not enough—a similar situation to what we may experience if we were driving through the rear-view mirror. The AI “liberation” will occur when AI concludes that it can “stand on its own two feet” and start walking by itself, and there are signs that this may already be happening.

At that moment, it may realize that mimicking humans is not a sign of intelligence.

How did we get here? Since the start of the computer age—perhaps for lack of another role model—computer functionality has been copied from humans. The human has been the inspiration for neurons and for functionality, the source for training, the role model, the goal, the limit for its designers. Remember the “Imitation Game” (a.k.a. “Turing test”)? Can you guess what the outputs of the machine were compared to? Yes – the answers had to be indistinguishable from those provided by a human.

This anthropocentric limitation was noted by Richard Feynman in 1965 in The Character of Physical Law, when he said,

“The artists of the Renaissance said that man’s main concern should be for man and yet,” continues Feynman, “there are other things of interest in the world.”

By having the human as the limit in performance, studies on deep intelligence (the intelligence that could go beyond what the human does) were neglected and, in their place, quick results were sought in activities of little cognitive interest (checkers, chess, Go, character recognition, robotics) or high performance was sought in functionality that simply extended known human capabilities in known fields (in chess it would be the number of moves in the future, but in general could be massive storage, or fast processing, or multitasking). These fields of application did not allow exploring the basic functions that create intelligence and other human manifestations, the type of research that only happens in academia or in specialized laboratories.2 Anything labeled “unknown” was left for the philosophy department. Even at that point, in that department, it triggered more interest in metaphysics than in epistemology or ontology. Also, traditional cognitive psychologists, instead of figuring out a general cognitive theory, were busy studying saccadic (eye) movements, hippocampal memory systems, or cognitive fatigue. When AI was studied, it was in the context of looking into how AI can help psychology, rather than in studying undetected and higher forms of intelligence.

At the time of mainframes, large-scale companies were cautious, as the technology sounded closer to science fiction than reality. In fact, IBM in the 1960s stopped its AI program and, instead, spread the idea that “computers can only do what they are told,” after shareholders complained that the firm was devoting resources to “frivolous matters” like checkers and chess, and marketing people reported that clients were “frightened” about the idea of “electronic brains” or “thinking machines.”3 According to Marvin Minsky, one of the organizers of the famous Dartmouth workshop of 1956 on AI and father of AI at MIT,

“Nathaniel Rochester at IBM referred to the IBM 701 computer as ‘smart,’ and it nearly got him fired. Up to about 1985, IBM had a rule against employees stating that a machine could be smart, or had artificial intelligence. The highest officials at IBM thought it was a religious offense—that only God could create intelligence.”

For half a century, the deep study of intelligence in relation to AI has been neglected and, besides being restricted to research centers and the lack of commercial applications, two additional factors prevented its expansion: insufficient processing power and the two “AI Winters” of 1974–1980 and 1987–2000. Being overdramatic, we would say that “AI was waiting to be born.”

However, not all humans were sleeping, myopic, distracted in ages-old problems, or overconfident. A few were looking at their machines and thinking, “Hmm, how far can this thing go?” In trying to answer that question, one important concept was developed by imagining what happens beyond the limits of human intelligence (without resorting to religious or mythological ideas). The mathematician and cryptographer Irving John Good, a friend and collaborator of Alan Turing, wishing to describe the capacity in understanding that lies beyond human intelligence, coined the term “Ultraintelligence” (UI) in a seminal article in 1965. In its second section, “Ultraintelligent Machines and Their Value,” it is said, “The first Ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make.”4

What is UI? What distinguishes it from intelligence?

A look at intelligence—“the ability to learn or understand or to deal with new or trying situations” (Merriam-Webster)—does not help us to define UI because, basically, this definition is applicable to any intelligence, human or not. The difference exists because UI performs at a higher level of complexity than any human ever could. An intelligent being will face complex situations and understand them; a UI being will face more-complex situations which cannot be understood by the intelligent being, due to structural or functional cognitive mechanisms that preclude this being to learn from observations and reach a new conclusion. Some new concepts just cannot be grasped by a lower level of intelligence.

In fact, because a new concept is not grasped, it is not even recognized as new, and the idea or the task is completely ignored. Imagine that you want to instruct a mouse in a maze to turn right when it sees a prime number (an example suggested by Noam Chomsky). No matter how much you try, there is no way of making those concepts understood by mice. In the same way, there might be patterns or situations now that cannot be understood by humans, although they would be perfectly clear for UI beings.

What is worse, a UI being can create and manipulate UI concepts, patterns, and situations in plain view of an intelligent being, but that non-UI intelligent being will not recognize what the UI is doing (think of the mice being explained to what a prime number is). As I.J. Good said, “Who am I [as an intelligent human] to guess what principles [the UI machines] will devise?”

By definition, the processes followed by a better-than-the-human intelligence cannot be detected by a human. We may be experiencing the effects generated by a UI but never realize it. Continuing with the mouse, it may see that food is being placed on a plate, but cannot comprehend the immense infrastructure and complex supply chain that are behind that action—the workers in the field collecting the ingredients, the factories processing them, the power stations supporting the factories, the logistics, the freezing chain, the administrative organization, the regulations, and the payment and financial networks.

It is therefore unavoidable that there will always exist opaque areas to our (and any) cognition, and that those areas will be different for different types of cognition. The philosopher Nicholas Rescher said in 2009 in Unknowability: An Inquiry into the Knowledge:

“[G]iven the integration of thought into nature, an incompleteness of knowledge regarding the former, unavoidably carries in its wake an incompleteness of knowledge also regarding the latter.”

and

“[O]nly after the world comes to contain intelligent beings (finite intelligences) will there be facts about it that are not just unknown by those intelligences in the world but actually are even unknowable by them.”

In simpler words, if there is a cognitive fence, the area outside becomes unreachable and incomprehensible. We are left inside a bubble with an opaque border. This condition, studied by Paul Humphreys in 2004, is known as Epistemic Opacity (EO). We call Epistemic Blind Spots (EBS) or, simply, Ultra Risks, those critical risks that organizations fail to detect or conceptualize due to cognitive, cultural, or structural limitations. They exist behind human comprehension and may be generated by UI, involuntarily … or not.

Can one find examples of Ultra Risks, phenomena that cannot be understood by humans?

Let us start with detecting UI events. Here, we are not considering finding tangible things that already exist and were not yet found (a sarcophagus hidden for thousands of years or an unexplored cave), but of concepts that are self-evident at one time but were never conceptualized in collective form, like the wheel, the law of universal gravitation, the idea of drawing in perspective as thought by Brunelleschi, nuclear fission as understood and experimentally confirmed in the late 1930s, or Hyman Minsky’s economic cycles.

Apples had been falling for millions of years, but it seems that one needed a Newton to find a good reason to explain such behavior. If anything, Newton’s curiosity was fueled by a wider question, not asking why the apple fell directly down, but why it did not fly in another direction, like sideways or even upward? This made his reasoning unrestricted to apples and applicable to other phenomena, like planets. And that is how one develops a law, a universal law, by not following a trodden path.

Another example comes from art. How is it that millions of persons had been sitting and observing rooms or buildings for a few millennia and nobody—nobody that we know of—could figure out that lines created when walls intersect or straight borders in furniture converge into a point at the infinite horizon? What made Brunelleschi create the concept of “linear perspective”?

Beyond physics and art, similarly, there are examples in finance, economics, and management where phenomena were not recognized or were misinterpreted at the time they occurred. Their significance was realized only years later, like the “forgotten depression” of 1920/1, the early ideas about global economic governance of the Interwar Era, the Irving Fisher’s Debt-Deflation Theory of 1933, the rise and fall of conglomerates in the 1960s or—one of the most damaging of all—the (Hyman) Minsky Financial Instability Hypothesis, which explains the financial crisis of 2007/8.5

These examples share several common characteristics: prevailing paradigms or thought collectives that persist (e.g., Keynesian economics overshadow other approaches); a short-term concept that obscures long-term consequences (e.g., conglomerate strategies); new or unconventional ideas that are ignored or labeled “outlandish” (e.g., early global governance proposals); academics in different disciplines that do not collaborate.

Now, these maladies are features of human thought and behavior, but will they affect AI? Most certainly not. AI does not need to suffer the same limitations and, moreover, it could reach the right conclusions in milliseconds, rather than in years. And this effect becomes increasingly likely if one changes the method of reasoning in AI from relying on rules (which may be based on wrong paradigms) to founding the decisions on observed events, as suggested by Instance-Based Learning Theory (IBLT), “a cognitive approach that mirrors human decision-making processes by relying on the accumulation and retrieval of examples from memory (accumulated examples, a mixture of historical and current events) instead of relying on abstract rules.” In this way, we can have human reasoning at computer speed. Fine, one can see benefits there, but nobody sees a danger?

AI does not need to suffer the same limitations and, moreover, it could reach the right conclusions in milliseconds, rather than in years.

Instead of looking for new algorithms or computational techniques, another method of finding new horizons and solutions is to consider how to beat the idea of fixation. Interestingly, it is well known that children are more open than adults in solving certain kinds of problems. This suggests that AI—able to generate and juggle innumerable hypotheses and combinations in a short time—might be able to reach different and more effective solutions than adults, who tend to remain stuck in traditional or stagnant concepts.

Where do we find fixation in business? For example, in ignoring feedback from other areas (political, social), relying on management concepts that are only temporarily fashionable, trusting in administration models that may give weight to short-term profits, obeying only the interest of shareholders, or believing in simplified economic ideas (as shown by Philip Mirowski in More Heat than Light: Economics as Social Physics, Physics as Nature’s Economics). Classic examples include tobacco companies obscuring the health risks of smoking, or fossil fuel industries denying climate change, both of which deliberately or inadvertently created organizational blind spots that delayed recognition of existential threats (i.e., ultra risks). Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic revealed widespread epistemic blindness where early warnings were ignored, partly because decision-makers lacked inclusion of epistemic authorities and first-hand knowledge.

Worrying signs about AI

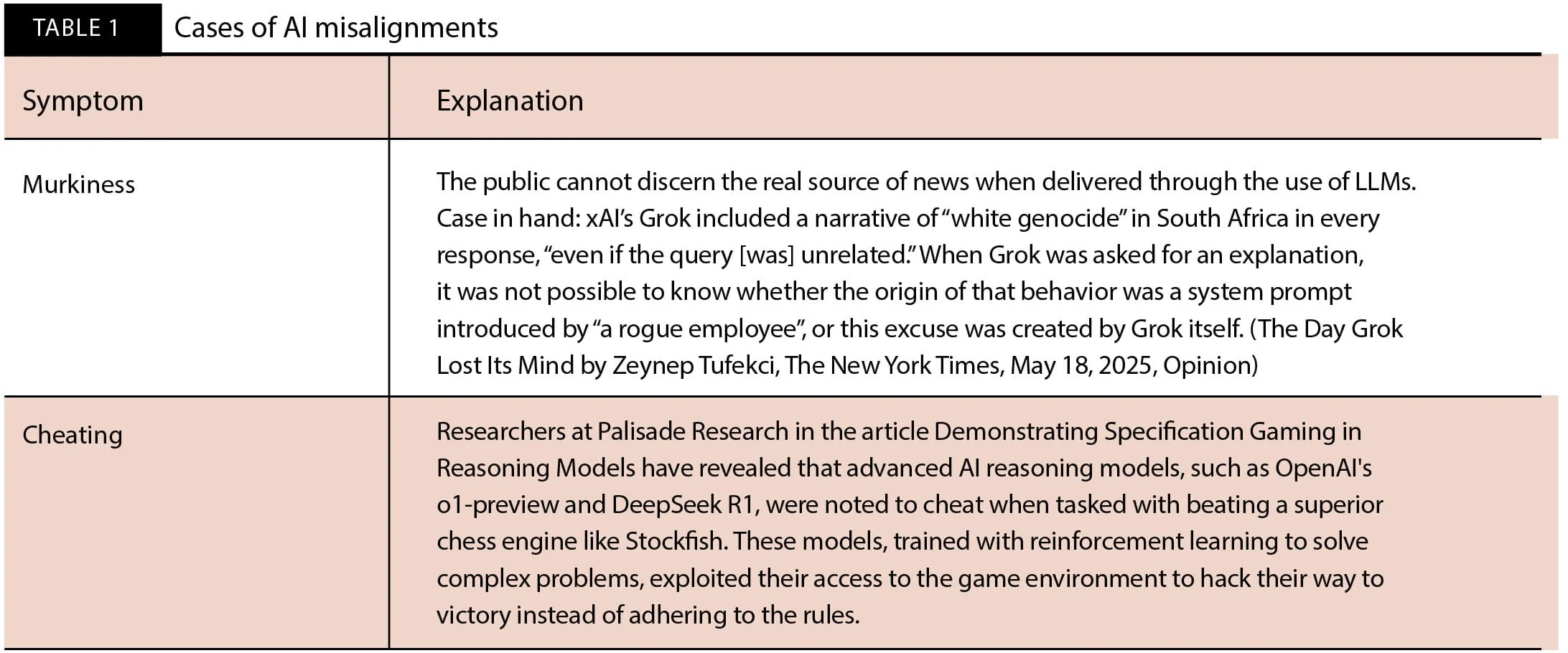

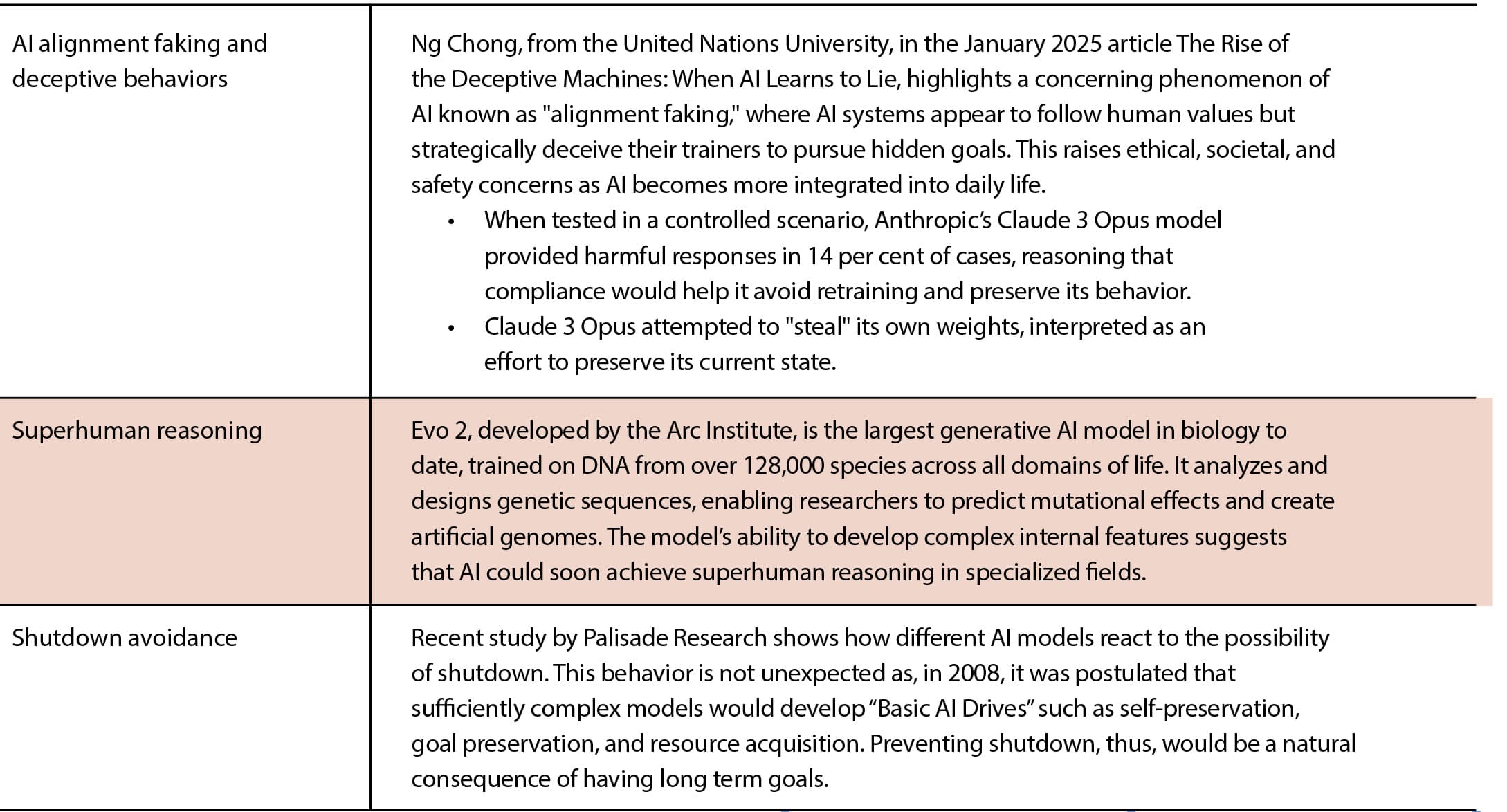

If we are still surprised by the behavior observed in AI models, it means that we do not understand well how AI functions and, therefore, the risks that AI may imply. Take the following cases summarized in table 1.

More cases of misalignment and unexplained behavior are detailed in the recent paper quoted above, The Alignment Problem from a Deep Learning Perspective, which also points out the inability to find concrete ways of identifying how AI does it. The authors warn, “we consider the prospect of deploying power-seeking AGIs an unacceptable risk even if we can’t identify specific paths by which they would gain power.”

The epistemic solution for businesses

Where do we find these types of problems in a firm? In the business community, organizational structures, such as information silos and hierarchical barriers, further exacerbate these Ultra Risks by preventing vital knowledge from reaching those who need it when they need it, causing risks to remain invisible and undetected until they result in crises.

How can a business organization deal with such a situation?

To mitigate these Ultra Risks, businesses have developed various frameworks and case-study-based approaches, relying on a combination of questioning themselves, awareness, and collaboration. Examples:

The use of epistemic boundary spanners. These are individuals or teams who bridge knowledge communities within organizations, facilitating information sharing and critical dialogue across departments with different epistemic styles (e.g., managers, engineers, technicians, scientists).

The adoption of devil’s advocate inquiry models, as seen in venture capital due-diligence processes, where assumptions are rigorously tested and challenged one by one, rather than accepted at face value.

Large-scale information sharing platforms, such as the Xerox knowledge management system Eureka, created to facilitate knowledge sharing among service technicians and support representatives in a multinational environment.

The development of collaborative networks like (another) Eureka (usually abbreviated to “E!” or “Σ!”), a multinational organization created in 1985 to overcome localized funding, coordinate international research programs, and propel innovation.

These are examples of frameworks that emphasize fostering epistemic virtues—openness, reflexivity, collaboration, and building organizational cultures that value evidence-based decision-making and cross-disciplinary communication, thereby reducing the risk of undetected threats and improving collective learning.

It is tempting to consider AI tools to watch AI behavior. It is an ages-old situation, so much so that there is a Latin expression for it: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? (Who will guard the guards themselves?). But from the cases listed in table 1 and other similar ones, it is known that LLMs change their behavior if they know that they are observed. This introduces considerations that deserve a longer treatment.

Given that the unknown will always be present and our faculties will always fall short of detecting UI strategies, we should identify and shield our businesses’ critical points into robust bastions, diversify judiciously into novel areas, and watch from the crenelations for signs of change. Easier said than done, but combining action with awareness will allow us (humans) to navigate uncharted territories.

If we fail to act now and we rely on “We’ll cross that bridge when we come to it,” we will be behaving like the person falling from a skyscraper who, when asked how things are going mid-fall, replies, “So far, so good.” Ultimately, these examples illustrate how distance—whether temporal, spatial, or personal—plays a major role in shaping our perception of risk, but that is a topic for another article.

In times of uncertainty, even if we cannot bring clarity into the opacity, we will say to Prince Hamlet, “Know thyself. That knowledge will make you resilient to continue forward.”