By Francis Hintermann, Madhu Vazirani, and Carsten Lexa

At first glance, it would be surprising to learn that Europe is lagging behind in the field of artificial intelligence. In this article, the authors elaborate on this reality and share 5 smart ways to increase Europe’s artificial intelligence quotient.

The era of artificial intelligence has arrived. Established companies are moving far beyond experimentation. Money is flowing into AI technologies and applications at large companies. Startups are inventing the next generation of game-changers. All of this is raising what we call the “artificial intelligence quotient”, or AIQ.

So Why does Europe seem to be Lagging Behind?

When it comes to AI, our assessment of G20 countries shows Europe is still very much a patchwork. Businesses across the region grapple with different regulations, cultural nuances, and wide-ranging concerns from consumers about a lack of personal privacy online. And small businesses in particular lack awareness of the opportunities to exchange ideas and innovations between AI hubs when trying to scale beyond their home market.

Compounding the challenge is a massive talent shortage in many disciplines of AI across the world and particularly in Europe. There are simply not enough skilled people to work AI jobs in Europe. And those who are skilled are fleeing to the US and China, drawn by their vibrant networks of entrepreneurs, university research and development programmes, and corporate tech communities. Right now, there are at least 5,000 vacant AI-related positions in Germany alone, according to Wolfgang Wahlster, CEO of the German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence. And Germany is one of the AI leaders in Europe.

Taken together, these factors give Europe a lower AIQ than North America and the Asia Pacific region. And the impact is measurable. In 2016, US-based AI startups attracted almost $2 billion in venture-capital investments, and Chinese startups raised $1 billion. By contrast, Europe-based AI startups raised only $600 million. What about priority patents, another critical indicator of progress? Chinese filings increased more than 20% in the past five years. In Germany, France, the UK, and the rest of Europe, the figure is only 5%. And, of the top 100 companies we have identified as “AIQ companies”1 – those which successfully balance in-house innovation with external collaboration – only 20 are European.

Stepping Up to the Opportunity

For big companies, AI presents the opportunity for business transformation. For entrepreneurs, it is a tool they can use to take on much larger incumbents. Policymakers have their own set of challenges, critical to both economic development and social stability.

Indeed, they must do two things at once: manage the fears about the impact of AI on society while encouraging innovation. Despite the ethical and workforce risks of AI being debated in Europe, there is a far greater risk to general economic wellbeing, workers’ earning potential, and global competitiveness from inhibiting development of AI. Research on a dozen major economies revealed that AI has the potential to double annual growth rates by 2035. But this won’t happen without the concerted efforts of many actors, including those in government.

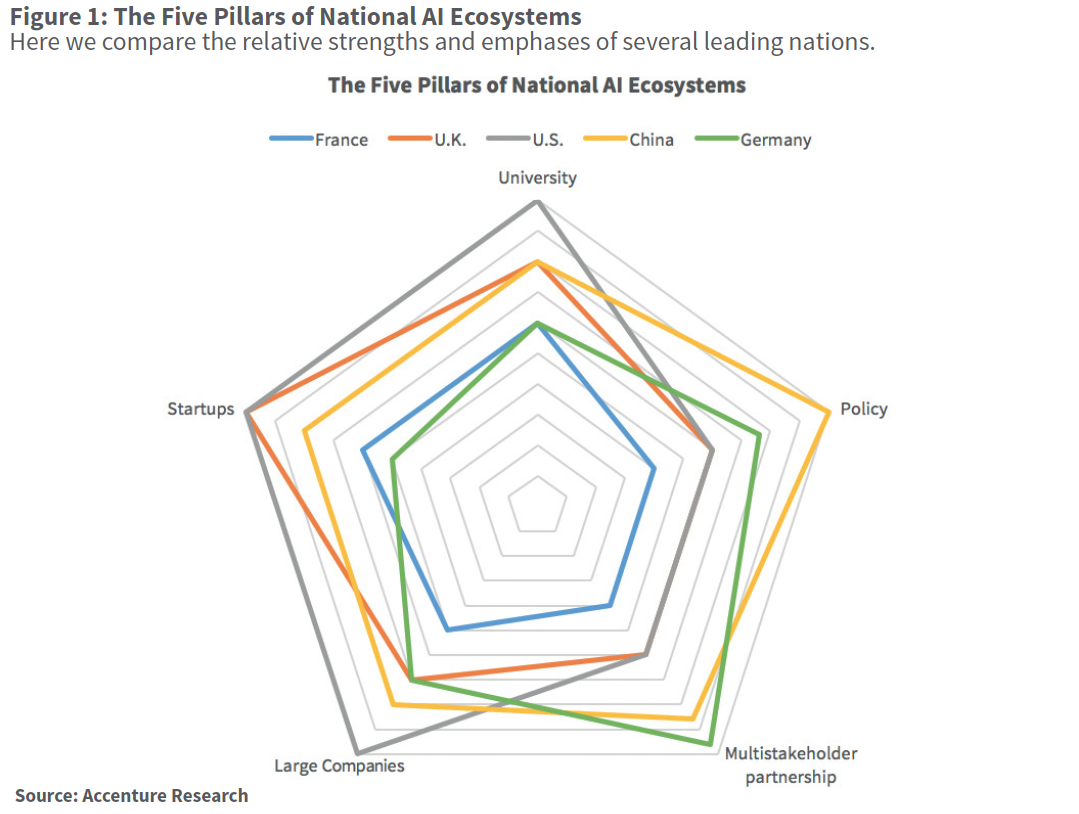

So where to start? We analysed AI innovation in 10 leading countries in Asia, Europe and North America. Our research shows that vibrant ecosystems are based on five pillars: universities, large companies, startups, policymakers and multi-stakeholder partnerships. The strength of these pillars will vary from one country to another. For example, in the US, AI growth has been driven largely by the private sector, while in China the government has played a greater role. (See Figure 1.)

To boost its AIQ, Europe must harness both an innovative private sector and a supportive policy and regulatory framework. Indeed, policymakers in Europe must act now to address the barriers to growth – with the help of enterprises, entrepreneurs, innovators, and researchers. The future development of AI in Europe is not just a regulatory issue. It requires a comprehensive response, particularly on issues relating to the regulation of data, research & development, collaboration between academic researchers and industry, alignment of infrastructure development, and retraining the continent’s workforce.

To understand how to foster growth and innovation while safeguarding consumer rights and ethical considerations, Europe’s AI stakeholders should consider the following five recommendations.

1. Strengthen the R&D ecosystem.

European governments should invest more in basic AI research and facilitate a vibrant ecosystem around the R&D hubs.

The European Commission has set up the Partnership for Robotics in Europe (SPARC), a public-private partnership to develop a robotics strategy for the region. With €700 million EC funding for 2014-2020, coupled with private investment for an overall backing of €2.8 billion, SPARC is believed to be the biggest civilian research programme in this area in the world. Looking at national strategies, the UK has launched a major review into how Britain can become a world leader in AI and robotics. France and Germany are also hard at work on developing national AI strategies.

While these are promising starts, governments in Europe need to do more to facilitate AI R&D by increasing state investment and providing infrastructure and other support to businesses. In China, governments play a deliberate and explicit role in funding scientific research (giving $800,000 to $1 million in subsidies to AI companies). In the US, universities and industries often partner to support technology innovation ecosystems for startups.

Certainly, there are bright spots in Europe. Consider the work already under way in the UK. The universities of Cambridge and Oxford stimulated the creation and development of several startups that achieved major AI breakthroughs and later became prime acquisition targets. Google in 2014 bought DeepMind, Apple in 2015 purchased VocalIQ, and Microsoft last year purchased SwiftKey. The next era of startups should see deep investment for longer-term outcomes to create AI-led “unicorns” – startups with valuations of more than a billion dollars.

2. Forge more multi-stakeholder partnerships.

The participants in any major technological movement need a safe space to go to share ideas, develop best practices and solve problems. But perhaps most critically, to allow technology transfer from basic research to applied research.

Consider what is happening in Germany. The German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI) is one of the world’s largest nonprofit contract research institutes for software tech based on AI methods. Founded in 1988, the centre now counts Google, Microsoft, SAP, BMW and Daimler as stakeholders and has facilities in Kaiserslautern, Saarbrücken, Bremen and Berlin.

And the manufacturing hub of Stuttgart is transforming itself into a AI research hub, with critical support from the country’s industrial giants Daimler, BMW, and Bosch. This new model of cooperation between science and industry emulates what Stanford University has done in Silicon Valley.

AI stakeholders should forge more such partnerships that allow for cross-pollination within the country, and importantly, between European countries and their AI innovation hubs.

3. Enable and broaden access to data.

AI innovation depends on massive quantities of data. The full economic and social potential of these emerging technologies will be met only if data is widely accessible. Governments have a key role to play, particularly in opening up data to small enterprises – which unlike large corporations might not have the resources to accumulate a critical mass of data.

For starters, governments can lead by example, by sharing public-sector data-sets through the creation of platforms that small enterprises can freely access. In addition, they should encourage the private sector and scientific and research institutions to share data and collaborate over such platforms, which can help support the development of vibrant AI ecosystems.

Governments could also remove regulatory obstacles to the analysis and testing of big data. In the US, “fair use” defences apply, allowing for commercial data mining within certain constraints and without infringing copyright. This has enabled innovation and allowed US companies using big data to thrive. While the European Commission has proposed a reform of copyright rules to introduce an exemption for “non-commercial use” data mining, this would only apply in a limited context. European governments should consider how to balance copyright and data protection with the benefits that would arise from commercial data mining, particularly for small enterprises.

Further, clarity of rules regarding the ownership of machine-generated intellectual property, as well as the practical application of the General Data Protection Regulation, could support the development of AI in Europe.

4. Create a workforce of the AI future.

To work in AI-related jobs, people will need an entirely new set of skills and capabilities. Companies will need to make radical changes to their training, performance and talent-acquisition strategies. At the same time, governments must do their part to equip their citizens with the STEAM skills – science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics – demanded by AI. And both the public and private sectors must make every effort to train those who were left behind such fast-moving technological developments in the past: minorities, women, working mothers and the disabled.

The goal should be to help workers not merely to be more productive, but to deliver more creative, precise and valuable work. This will involve fostering a culture of lifelong learning, much of it enabled by technology: personalised online courses that replace traditional classroom curricula and wearable applications such as smart glasses that improve workers’ knowledge and skills.

Success will also depend on partnerships between startups, universities and individual experts to access knowledge and skills at scale. For example, the Artificial Intelligence French Initiative (“#FranceIA”) recommends deeper collaborations between the private and the public sector to develop new AI skills at scale in France.

5. Embrace smart regulation to safeguard responsible AI.

AI will be more beneficial if governments follow a set of guiding principles that are “human-centric” – the keys to this are accountability, fairness, honesty, and transparency.

Just as companies must be responsible, governments must consider how to promote trust while preserving the maximum flexibility to innovate. This requires smart regulation that adapts to the shorter innovation cycles of AI. One example is autonomous-vehicle insurance. Looking to the future, the UK Department for Transport has proposed new two-way insurance policies that cover motorists whether they’re driving or not. When the car is in driverless mode, insurance companies would recover the costs of claims from the party responsible for the crash, which may be the manufacturer.

Policymakers and standards bodies should also work with businesses that are advanced in AI in order to learn how they are developing their own responsible AI practices. These private-sector efforts can help inform future public policy.

A Call to Action

An individual can boost her IQ through mental exercises. We believe Europe can also take steps to boost its AIQ. Business and policy leaders will have to bring a Europe-focussed, “people first” mindset to the effort.

Time is short. Among the world’s largest companies and economies in AI, only a small minority demonstrate high levels of AIQ. Those that join them in the coming years will enjoy the greatest potential for growth and sustained market leadership.

About the Authors

Francis Hintermann (left) is global managing director of Accenture Research, based in New York. Madhu Vazirani (centre) is a principal director with Accenture Research, based in Mumbai. Carsten Lexa (right) is an attorney and president of the G20 Young Entrepreneurs’ Alliance in Germany.

Francis Hintermann (left) is global managing director of Accenture Research, based in New York. Madhu Vazirani (centre) is a principal director with Accenture Research, based in Mumbai. Carsten Lexa (right) is an attorney and president of the G20 Young Entrepreneurs’ Alliance in Germany.