By Alessandro Lanteri, Massimiliano (Max) Cappuccio and Mark Esposito

The autonomous vehicle revolution is real, but not imminent. Here’s how to navigate the gap between hype and reality.

When will we finally have autonomous vehicles transporting us safely and reliably along our streets and highways with no human intervention? Well, the truth is, it’s going to take a while. Read on to discover why, no, we’re not nearly there yet.

Perhaps you’ve heard that autonomous vehicles (AVs) are soon coming to a road near you. Waymo recently announced it1 will offer driverless taxi services in London next year. Similar news keeps popping up elsewhere, in Australia,2 China,3 Europe,4 and the Middle East,5 involving tech companies like Amazon6 and carmakers like BMW.7

If you’ve been tracking AVs for a while, however, you’ve heard it all before. Back in 2015, Elon Musk predicted Tesla would demonstrate full self-driving capability from Los Angeles to New York by 2017.8 In 2018, Cruise announced plans to launch a commercial robotaxi service by the following year.9 Waymo’s CEO John Krafcik stated in 2018 that the company would launch a fully autonomous ride-hailing service “very soon.”10

Today, in late 2025, you still can’t buy a truly autonomous vehicle for unrestricted use. While Waymo operates robotaxis in limited areas of San Francisco, Phoenix, and Los Angeles,11 these services come with significant geographic and operational restrictions. In October 2023, Cruise suspended all driverless operations and only recently reinitiated them.12

What happened? And more importantly, what should you do now?

The final capabilities required to commercialize a complex system often demand disproportionate time, resources, and innovation.

The answer reveals a critical insight about technological transformation: the final capabilities required to commercialize a complex system often demand disproportionate time, resources, and innovation (Hobday et al., 2000). In autonomous driving, this “last mile” problem is particularly acute, and understanding it is essential for anyone making strategic decisions in transportation, logistics, insurance, real estate, or urban infrastructure.

Why incremental progress feels like failure

Autonomous vehicles demonstrate a paradox: continuous technological advancement alongside persistent commercialization delays. This isn’t failure. It’s the natural pattern of solving exponentially difficult problems.

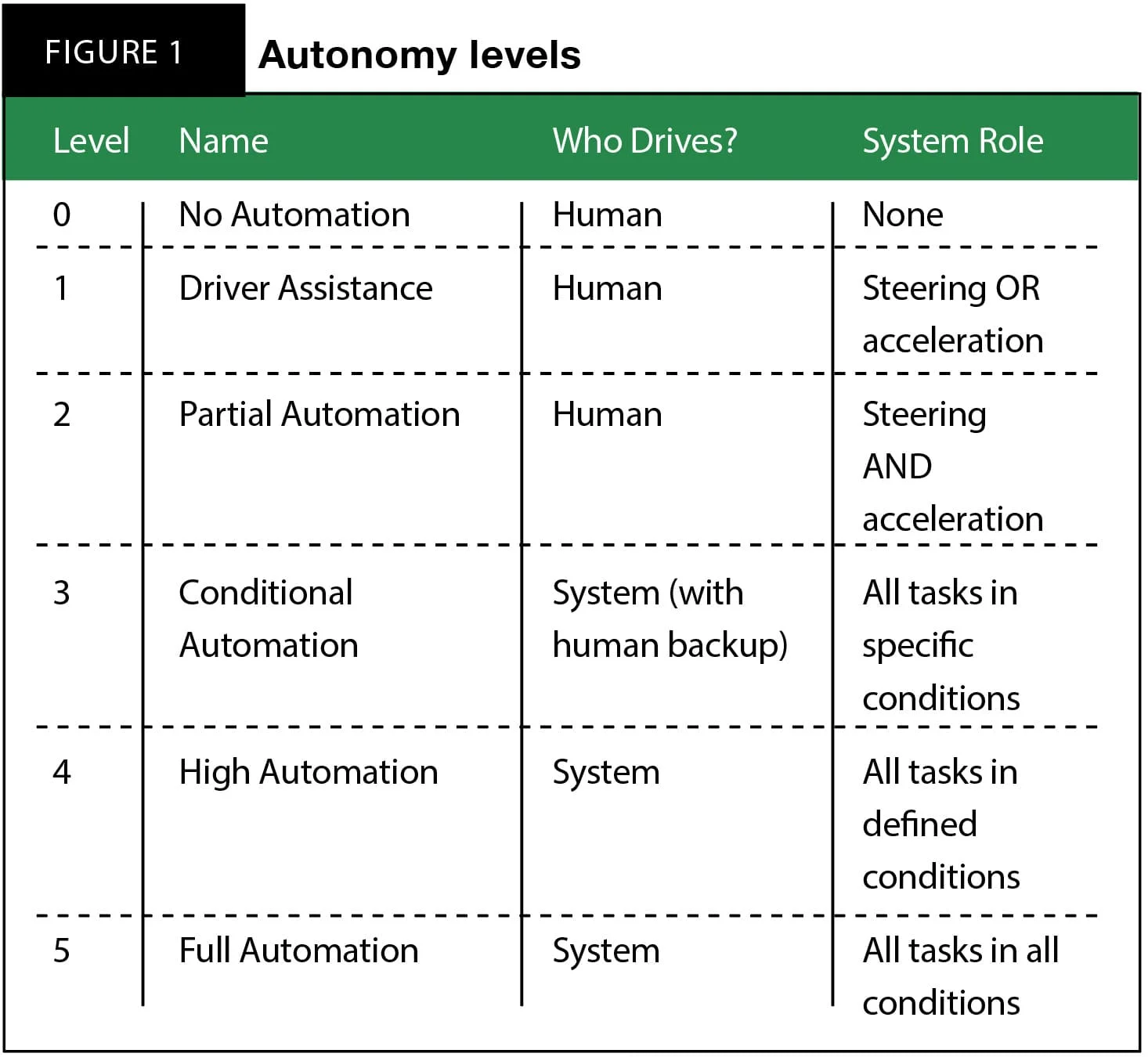

Current systems excel at what engineers call the “easy 80 percent.” Highway lane-keeping in clear weather has been solved. Adaptive cruise control in steady traffic is now routine. These capabilities exist today in commercially available SAE Level 2 systems (figure 1 next page) from manufacturers including Tesla, Mercedes-Benz, and General Motors. Companies have demonstrated impressive progress in controlled environments. But the remaining 20 percent, handling the infinite variability of real-world driving, proves exponentially more difficult. This reflects what researchers call the “long tail” problem in machine learning: rare events that are individually unlikely but collectively inevitable across large-scale operations.

Consider scenarios that AVs encounter regularly: construction zones with temporary traffic control devices, where human flaggers direct vehicles contrary to posted signs. Or intersections where police officers manually direct traffic. Or navigating around vehicles during adverse weather while managing sensor degradation from precipitation. These aren’t edge cases. For logistics companies running hundreds of routes daily across diverse geographies, they represent regular operational challenges.

A recent extensive literature review, by two of us along with several co-authors, found that autonomous systems fail not from single weaknesses but from tightly interconnected constraints spanning technology, infrastructure, human factors, and governance (Dong et al., 2025): improving perception systems doesn’t help if planning algorithms can’t handle uncertainty; better planning doesn’t matter if infrastructure lacks standardization; infrastructure improvements stall if regulations aren’t harmonized across jurisdictions. This interconnectedness explains why deployment timelines keep extending despite genuine technological progress.

Four fundamental barriers

1. Perception systems hit physical limits

AVs must perceive their environment with superhuman reliability, but current sensors face fundamental physics constraints. Modern AVs use cameras, LiDAR (light detection and ranging), radar, and ultrasonic sensors to build real-time environmental models. In optimal conditions (i.e., dry pavement, good lighting, clear lane markings), these systems perform admirably. But optimal conditions are less common than initial assumptions suggested.

Weather degradation is significant. Heavy rain reduces LiDAR range while creating false returns from water droplets. Fog significantly degrades both camera and LiDAR performance in dense fog. Snow creates multiple challenges: it obscures lane markings essential for localization, accumulates on sensors, reducing their effectiveness, and creates highly reflective surfaces that confuse perception systems. Sun glare presents another persistent challenge. Cameras can become completely saturated when facing direct sunlight, making object detection impossible for critical seconds. This isn’t a mere inconvenience. At highway speeds, even brief perception failures create substantial risk.

These aren’t hypothetical concerns. In 2018, an Uber autonomous test vehicle struck and killed a pedestrian13 partly because the perception system failed to correctly classify the pedestrian crossing outside a designated crosswalk. While this incident occurred in clear conditions at night, it illustrates how perception failures in non-optimal scenarios can have catastrophic consequences.

Implications: Early commercial deployment will concentrate in regions with favorable conditions, consistent weather, well-maintained infrastructure, simple traffic patterns. Waymo’s initial deployment focus on Phoenix, Arizona reflects this reality: the region offers over 300 days of sunshine annually, minimal snow, and relatively predictable weather.

2. The common sense gap remains unbridged

Every experienced driver handles this scenario instinctively: approaching an intersection when a child’s ball rolls into the street. You immediately slow down, anticipating that a child might chase it. This prediction requires no special training, just common sense about how the world works. Current AI systems struggle with this type of reasoning.

The challenge isn’t pattern recognition. Modern computer vision can identify balls, children, and other objects with high accuracy in standard datasets. The problem is understanding what objects mean in context: inferring the presence of unseen children, predicting their likely behavior based on age and situational factors, and adjusting driving behavior accordingly.

This represents the gap between narrow AI (excellent at specific trained tasks) and general intelligence (reasoning about novel situations). AVs must constantly interpret ambiguous situations using context, experience, and what researchers call “commonsense reasoning” (Davis & Marcus, 2015).

Consider the challenge of understanding human gestures and intentions. When a pedestrian makes eye contact with a human driver, both parties engage in complex negotiation about who will proceed first, a process that depends on cultural norms, contextual factors, and subtle body language cues. Teaching AI systems to participate in this negotiation remains an open research problem.

The SAE Level 3 automation category exemplifies these challenges. At Level 3, vehicles can drive autonomously in specific conditions, but humans must remain available to retake control when systems reach their limits. However, drivers require an average of 5-7 seconds to regain situational awareness and respond effectively after disengaging from monitoring tasks (Gold et al., 2013), too long to safely intervene in complex scenarios, particularly at highway speeds.

Mercedes-Benz introduced the SAE Level 3 system,14 but with significant restrictions: it operates only on approved highways, at limited speed, and in heavy traffic or congestion. These limitations reflect the difficulty of the human-machine hand-off problem.

Implications: True Level 5 autonomy (drive anywhere, anytime, in any conditions) requires solving commonsense reasoning and situational understanding. Until then, AVs need carefully defined operational design domains (ODDs), specific routes, scenarios, and conditions where their narrow intelligence suffices. Executives should be skeptical of vendors promising universal capability in the near term.

3. Infrastructure wasn’t built for machines

Roads were designed for human perception and judgment. This legacy creates systematic challenges for autonomous systems.

Lane markings present a fundamental challenge. Human drivers easily follow faded, partially obscured, or non-standard markings using contextual understanding and general knowledge of road geometry. AVs typically depend on detecting high-contrast, standardized markings for lateral control and localization (Yenikaya et al., 2013). Lane marking quality varies dramatically even within developed nations, with many road markings too degraded for reliable machine vision detection, especially on rural roads.

Roads were designed for human perception and judgment. This legacy creates systematic challenges for autonomous systems.

Traffic signs and signals present similar issues. While AI achieves over 98 percent accuracy on standardized datasets like the German Traffic Sign Recognition Benchmark (Stallkamp et al., 2012), real-world conditions are messier. Signs are often: partially obscured by vegetation, vehicles, or infrastructure; faded from sun exposure or weathering; non-standard in design, placement, or mounting height; supplemented by temporary signs during construction; and subject to vandalism or graffiti.

The challenge extends beyond detection to interpretation. A “road work ahead” sign might be followed by any number of actual road configurations e.g., closed lanes, narrowed lanes, detours) or sometimes no visible construction at all. Human drivers handle this ambiguity through cautious adaptation. Programming autonomous systems to respond appropriately to every possible scenario remains difficult.

Digital infrastructure adds another layer of complexity. Advanced AV systems rely on high-definition (HD) maps that capture road geometry, lane configurations, traffic control devices, and even curb heights with extreme precision. But who maintains these maps? When construction closes a lane or changes traffic patterns, how quickly does that information update? If a pothole opens or a sign falls, what’s the propagation delay to all vehicles?

Waymo creates and maintains its own HD maps for operational areas,15 with dedicated teams that drive routes regularly to capture updates. This approach works for limited geographic deployment but doesn’t scale to nationwide or global operations without substantial infrastructure investment.

Implications: Infrastructure readiness varies enormously by location. New planned communities with standardized designs, fresh markings, and comprehensive digital mapping will support AVs far better than older cities with inconsistent infrastructure and limited maintenance budgets. Companies evaluating AV deployment often discover that their anticipated operational zones require infrastructure improvements. This cost is usually absent from initial ROI calculations.

4. Human factors compound technical challenges

Even when technology works as designed, human psychology creates unexpected complications. Trust calibration represents a critical challenge. People simultaneously over-trust and under-trust autonomous systems (Hoff & Bashir, 2015). Both patterns create risk.

Over-trust leads to dangerous complacency. Drivers often engage in non-driving activities (phone use, eating, reading) despite clear warnings that they must remain attentive. This misuse contributed to several crashes. In 2016, the driver was watching a video16 when his Tesla, operating on autopilot, failed to detect a crossing truck. Conversely, under-trust causes people to intervene unnecessarily or reject technology entirely. Many users of advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) disabled features like lane-keeping assist because they didn’t trust the system’s decision-making, even when the system operated correctly (Ekman et al., 2019).

The optimal middle ground, appropriate reliance based on accurate understanding of system capabilities and limitations, proves elusive. Achieving proper trust calibration requires transparent system design, clear communication of limitations, and consistent performance. Current AV systems struggle to meet these requirements.

Cultural variation adds complexity for global deploy-ment. For example, while Japanese have broadly positive levels of acceptance of AVs, Germans have broadly negative attitudes, and Britons are overall neutral (Taniguchi et al., 2022). These differences likely reflect varying cultural attitudes toward technology adoption, trust in institutions and corporations, regulatory expectations, and tolerance for risk.

Implications: Human factors are deployment prerequisites, not afterthoughts. Driver training programs, transparent communication about capabilities and limitations, robust handoff protocols for partially automated systems, and community engagement are as critical as the technology itself. Organizations should budget time and resources for human-factor research and intervention design alongside technical development.

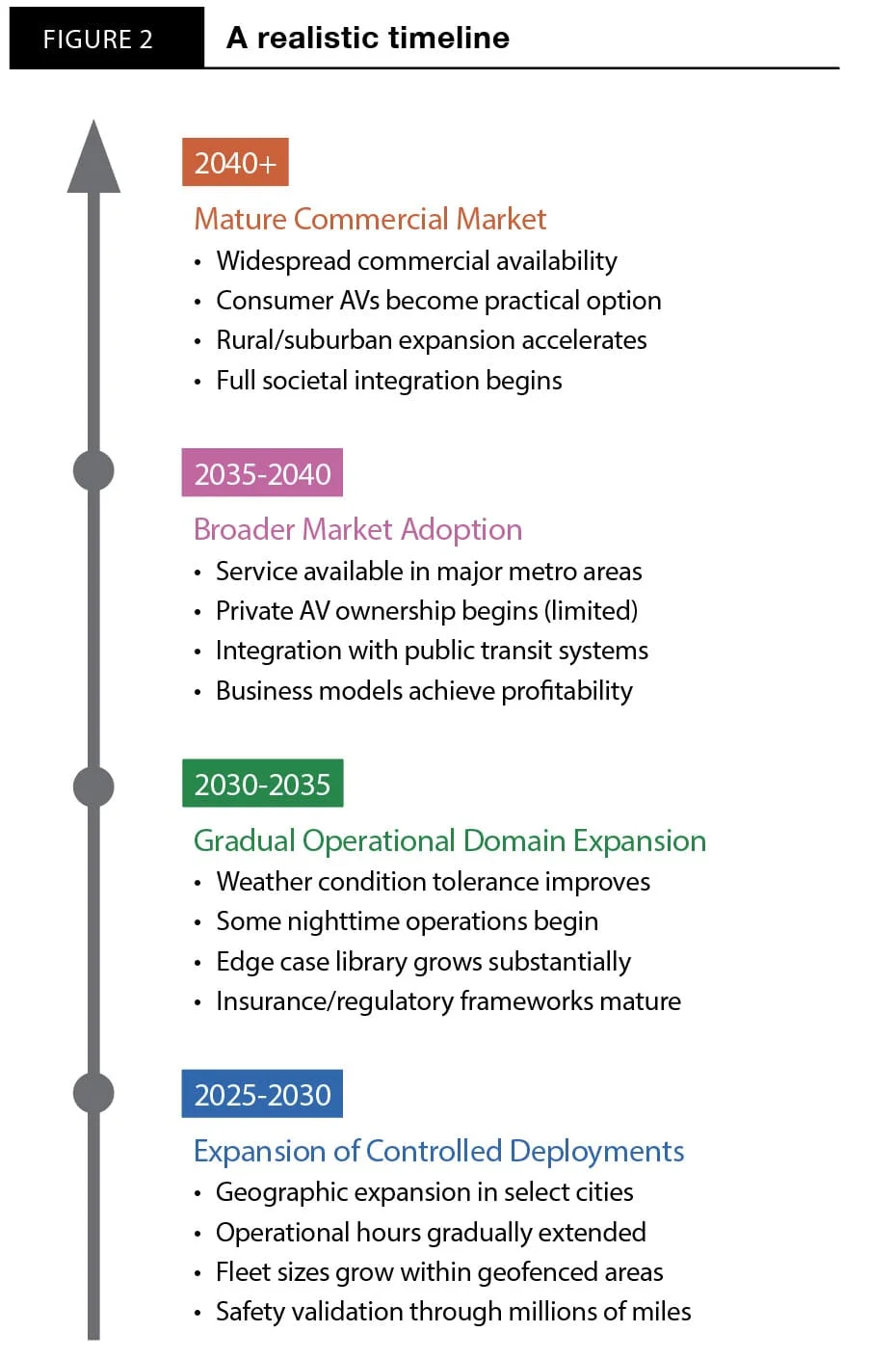

The path to widespread AV deployment will likely unfold in distinct phases over the next two decades. Rather than a sudden transition, commercialization will proceed incre-mentally as companies methodically expand operational domains while maintaining safety standards.

2025-2030 represents a continuation of current trends: controlled deployments in favorable conditions expanding geographically but remaining constrained by weath-er, time of day, and operational design domains. Companies will accumulate the mil-lions of miles necessary to validate safety claims and refine their systems against real-world edge cases.

2030-2035 may see gradual relaxation of some operational constraints as weather tolerance improves and nighttime operations become feasible. During this pe-riod, the regulatory and insurance frameworks will mature alongside the technology, establishing clearer pathways for broader deployment.

2035-2040 could mark the beginning of genuine market adoption, with robotaxi services available across major metropolitan areas and the first viable private autono-mous vehicles entering the consumer market. Integration with existing transit systems will help establish autonomous mobility as a practical transportation option.

Beyond 2040, assuming continued progress, we may finally see the widespread commercial availability that has long been promised. Consumer ownership of autono-mous vehicles will become practical for those who can afford them, and deployment will begin expanding into suburban and rural areas where operational challenges are less severe.

Note: This timeline assumes steady technological progress without major break-throughs or catastrophic setbacks. Regional variation will be substantial, with some cit-ies achieving mature deployment years earlier as others lag behind due to regulatory constraints, infrastructure limitations, or challenging weather conditions. The economic viability of autonomous vehicles at scale remains an open question that will signifi-cantly influence adoption rates.

Recommendations

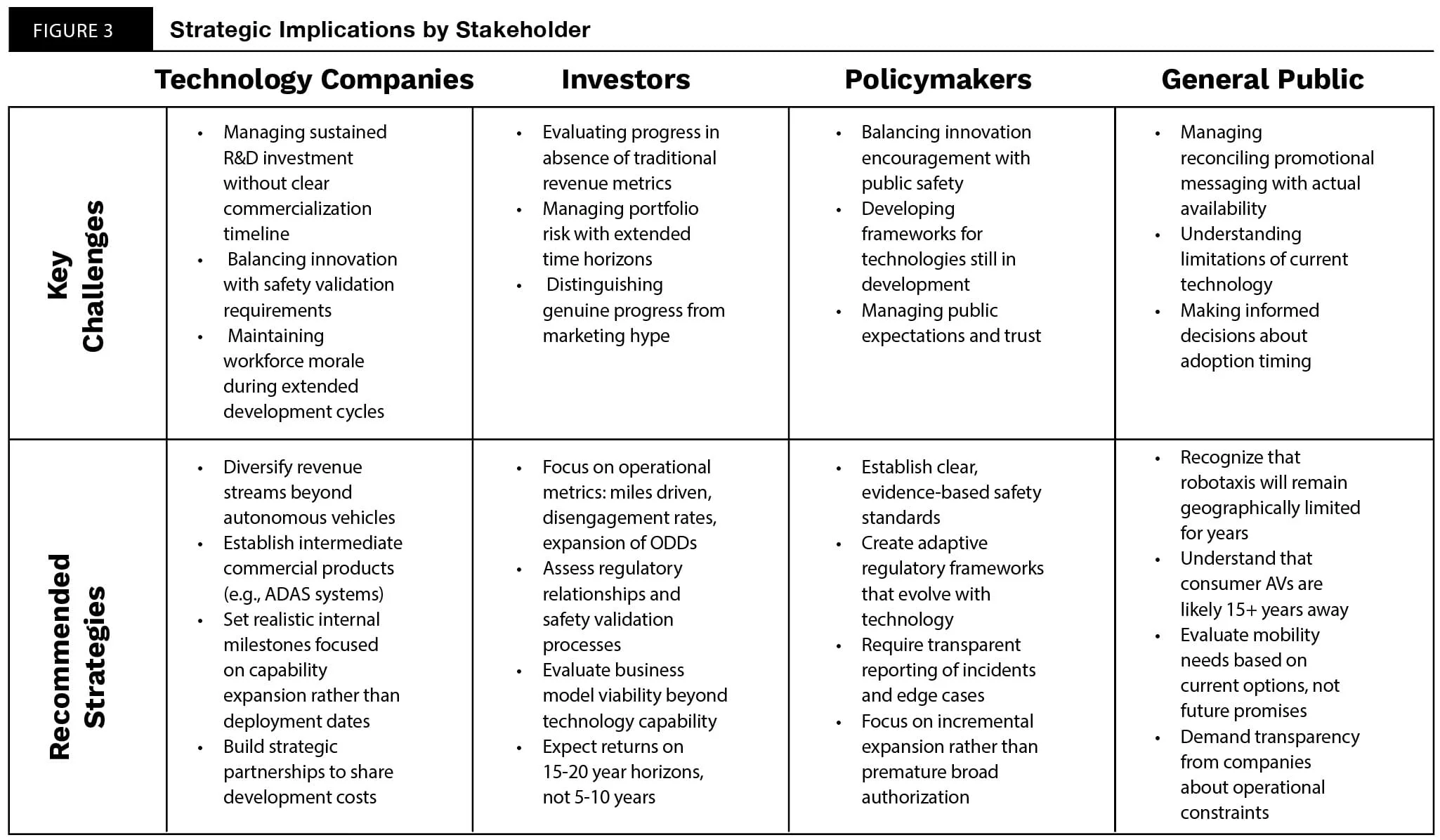

The extended timeline for autonomous vehicle commercialization (box 1) requires fundamentally different strategic approaches across stakeholder groups. Figure 3 (next page) outlines key challenges and recommended strategies for each major stakeholder category.

The common thread across all stakeholders is the need to abandon optimistic timelines, hyped in the news, in favor of realistic expectations grounded in the genuine complexity of the challenge. For technology companies, this means building sustainable business models that can endure decades of development. For investors, it requires patience and focus on meaningful operational metrics rather than premature revenue projections. For policymakers, it demands adaptive frameworks that balance innovation with public safety. And for the general public, it means making transportation decisions based on currently available options rather than promised future capabilities.

The companies that will ultimately succeed in commercializing AVs are those investing in sustainable, long-term development programs, rather than pursuing unrealistic promises of imminent breakthroughs. Similarly, the regions that will see successful deployment first are likely those with regulatory frameworks that prioritize incremental expansion based on demonstrated safety rather than competitive pressure to approve unproven systems.

The long game

The AV revolution is real, just slower and more complex than initially forecast. The technology will ultimately transform transportation, logistics, urban planning, and numerous adjacent sectors. But transformation will unfold over decades, not years.

For executives, this timeline demands a balance of serious engagement without over-commitment. Winners will be organizations that:

- maintain realistic expectations about capabilities and commercialization timing, based on evidence rather than vendor promises;

- invest in learning and piloting without betting core business operations on near-term deployment;

- build ecosystems and partnerships to address interconnected challenges across technology, infrastructure, regulation, and human factors;

- stay flexible as technology, regulations, and markets co-evolve in unpredictable ways;

- capture value from interim capabilities (enhanced driver assistance, route optimization, electrification) while preparing for eventual full autonomy.

The last mile isn’t a single problem requiring a clever engineering solution (Dong et al., 2025). It’s a web of interconnected challenges demanding coordinated progress across technology, infrastructure, human factors, and governance. Organizations understanding this complexity and planning accordingly will be positioned to capture value as autonomous vehicles gradually transition from impressive technology demonstrations to commercially viable systems.