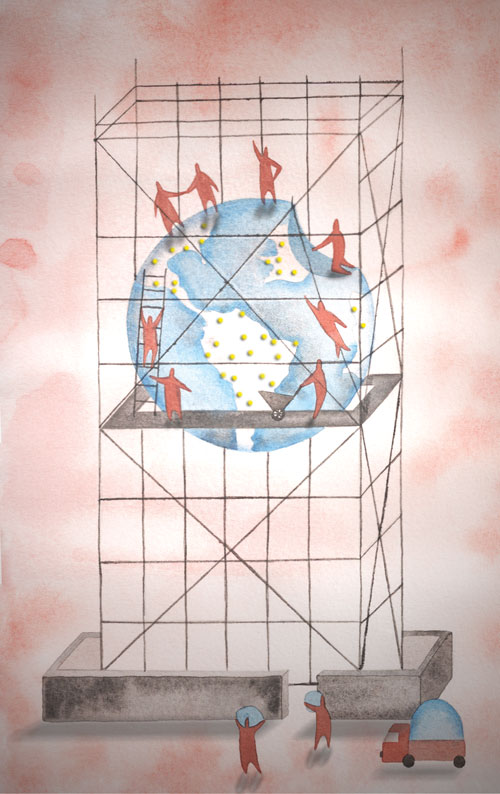

The matrix structure is here to stay, but its complexity can be minimized, and companies can get more value from it

The way a company organizes itself—how it allocates responsibilities, how it organizes support services, and how it groups products, brands, or services—can have a substantial impact on its effectiveness. Global companies, however, find structure difficult: in our recent survey of over 300 senior executives,1 only 44 percent agreed that their organizational structure created clear accountabilities.

Global companies find structure difficult because there are no simple solutions—most global structural options create challenges as well as benefits. For example, many companies have focused for years on standardizing structures; easily understood and navigated structures simplify costs and make sharing of risk and information easier and therefore support many of the benefits of being global. However, global companies are now often finding that they are reaching the limits of this benefit—their standardization has become so thorough that they find it hard to achieve the flexibility needed to respond to local market requirements. Many are therefore starting to revisit the trade-off between standardization and local flexibility.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

Another structural challenge faced by global companies is creating the right balance between minimizing complexity (making it easy to get things done and get decisions made) and capturing knowledge and innovation. It is often hard to get things done in a global organization due to its size and the multiple time zones that it encompasses. In addition, the inevitable duplication of some activities across businesses, regions, and functions creates uncertainty about where to go to get a task completed or a question answered. One way to solve this is to create self-contained, vertically integrated, global businesses within which decisions can be made quickly and complexity is minimized. However, such silos make it much harder to find, share, and benefit from knowledge across businesses. In our survey, for example, only 46 percent of senior executives felt that ideas and knowledge were freely shared across divisions, functions, and geographies within their companies.

For most global organizations, these trade-offs are greatly influenced by their archetype. For example, the right answer to the trade-off between complexity and knowledge sharing for a customizer company, which tailors its products and services to each market and which therefore needs to create a lot of local innovation wherever it operates, is likely to be very different than it is for a global offerer, which offers standardized products.

Other issues may also affect these trade-offs. For example, the correct answer to the trade-off between standardization and local flexibility may vary across markets even for the same business; there may be a need for greater delegation in dynamic high-growth markets, where decisions need to be taken more quickly, than in established developed markets. Likewise, the way in which a company has grown can also be important. If, for example, a company has grown organically, it may have a high degree of structural standardization; its biggest challenge may be deciding how to flex the model to allow more local tailoring. If a company has grown inorganically, it may have the opposite problem: country or business silos may operate relatively independently and be difficult to standardize globally.

Given the complexity of these issues, it is not surprising that many global companies end up creating highly complex structures that incorporate multiple businesses within a matrix of business, functional, and geographic structures. As one executive told us, “The overall matrix between geography, service line, and global function in our company is, at best, cumbersome: this is no way to out perform local competition in fast-moving markets.”

Emerging thinking on new structures

Each company will, of course, face a somewhat different mix of the challenges described above, depending on their archetype, their strategy, and their history. Nevertheless, we see a number of approaches emerging that may in time help global companies find the right structure for their situation.

Be clear about what needs to be global. Globalizing businesses, products, or functions can make it easier to capture strategic and cost benefits, and to share knowledge and skills to drive innovation. This could mean moving from a geographic structure—say, three regional product development centers—to a single global structure that groups all related activities together. For example, a global publishing company recently created “global verticals” of people who work on similar publications in every country. This made it easier to exchange ideas on those types of publications and increased innovation. And that added more value than the previous geographic structure, which had only made it easy for people working on different kinds of publications in the same country to share information.

Focus country organizations on what needs to be local. Even as they determine what needs to be global, companies need to be just as deliberate in deciding what should be local. Globalization can destroy value if the activities globalized in fact need to be locally tailored. The publishing company reorganized with that awareness. Although many activities were globalized, country managers were retained to manage sales and marketing operations, which require much more local customization; some back-office services (such as local finance and HR support) were also left under local management and they managed the interface with global shared services.

The right answer here will be affected by the organization’s archetype. But this is not the only consideration; other issues can be just as important. In industries where local risks can threaten an entire organization—such as oil and gas, metals and mining, and even audit—global transparency on risk is critical and therefore risk processes need to be more globalized.

The expected growth rate of a market can also be important. Markets that are growing rapidly often require more local decision making on issues needed to compete, such as product innovation, marketing, and partnering. More activities will likely need to be localized when a company first enters a market and is less familiar with it (this may particularly be the case in emerging markets, where building relationships with local stakeholders such as regulators and governments is often critical). As the local business grows, some of this decision making may be taken back above the country level to the business division or corporate center. Companies need to think through all these issues systematically in deciding what should be local, and be aware of both the benefits and constraints of localizing decision making as well as the possibility that the right answer may vary by business as well as by country.

Be clear on the logic for regional structures. A traditional rationale for regional structures was the need for a “span breaker” within a global organization, to gather information from local organizations and pass it to the corporate center. As communication and travel across geographies becomes easier, this role is often far less important and does not have to be done within a regional structure. Given that regional structures are often expensive—they quickly start to duplicate corporate functions such as finance, HR, and marketing which also exist at both local and global levels—we are starting to see a trend toward either removing or radically reducing the size of regional offices. In some cases, companies have reduced these offices to small teams of 10 or fewer, which focus on people (rather than business) performance management, coaching, and business intelligence activities such as spotting regional and country risks, competitive risks, and opportunities. These new regional structures typically do not spend time aggregating financial or other data at a regional level and then reaggregating it at a global level.

There are, of course, exceptions to this trend; in organizations where the logic for regional structures is clear, the personnel should be retained. For example, some companies are retaining them if a corporate function tends to operate regionally (procurement, for example, if suppliers operate regionally) or if major competitors are regional. In emerging markets, regional structures can be important if the company seeks to build capabilities that are specific to operating in faster-moving markets (e.g., new innovation approaches). But even in these cases, companies will benefit from making sure that these structures are not duplicating other activities that add more value by being done globally or locally.

Companies should also consider whether the underlying premise of many regional structures—the traditional logic of managing countries in groups based on their proximity—is still valid. As barriers to travel and communication fall, it may make more sense to group companies according to their strategic needs and rate of growth if these are more important in determining the support needed from a regional office. However, when doing this, it is important to assess whether the new structures that are being created contain roles that are sustainable over time.

Create small physical corporate centers that focus on external reporting, serving the board, and holding the brand and values of the organization. Other elements traditionally housed in the corporate center (such as strategy, HR, procurement, and supply chain) can be retained in the corporate center (or global shared services), but in some cases, they can be relocated to the physical region where they add the most value.

New ways to manage complexity. Inevitably, organizing a global company will require a matrix, but the complexity this creates can be minimized. We know from our research on organizational complexity2 that getting accountabilities right—making it clear who is responsible for what and removing duplications in responsibility—is one of the major ways in which companies can make it easier to get things done. So, for example, a company could create a network of marketing experts to share knowledge and skills across the enterprise on issues such as new communications approaches, while leaving the responsibility for decision making on these issues to the local management. With minimal duplication, and managers who are trained and given incentives to be highly collaborative, this approach will add value from shared knowledge without reducing local flexibility. Standardizing structures—for example, in this case, making marketing roles relatively similar across businesses—makes it easier to create these links. Companies are also now reducing complexity by decreasing the number of cells within the matrix structure rather than assuming that every intersection within the matrix requires separate management: Unilever recently reported that it had reduced the number of its managed organizational units from more than 200 to 32.

Create end-to-end global business services with clear customer interfaces. Most global companies have long since brought widely used services—IT, HR, purchasing, financial reporting, and the like—together across their businesses and regions. We are now starting to see the next step in the evolution of these services, one that can increase business effectiveness and reduce cost. A few companies, such as P&G, DHL, and Unilever, are integrating back-office services from several functions so that a comprehensive package of services is provided for discrete processes—for example, integrating HR and financial data to support a single reporting process. This approach can remove some hard-to-spot duplication between functional tasks and create services that are better suited for users’ needs. It also means that a senior manager can have a single point of contact for global business services, rather than separate links into each shared service function. And providing all the services needed for a given process can also help firms capture greater economies of scale and create more attractive roles for services leaders.

We believe that the rebalancing of many global companies toward emerging markets combined with the accelerating pace of communication technologies opens up a whole new set of structural options. By being thoughtful about the global-local balance within their companies, the role of regions, the corporate center and business services, companies can create organizations that capture global benefits while remaining locally agile.

Copyright © 2012 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved.

About the Authors

Suzanne Heywood leads McKinsey’s organisation design practice in Europe, the Middle East and Asia and has co-led, over the last two years, McKinsey’s work on creating effective global organisations. She has previously written on a range of topics including restructuring companies, reducing organisational complexity and on preparing companies for growth. She serves clients across different industries on topics ranging from increasing efficiency through increasing organisational speed and agility to preparing for growth. She has a science PhD from Cambridge University. Suzanne is a partner in McKinsey’s London office.

Roni Katz works with global companies on organisation topics. She has deep expertise on organisation design: she led much of McKinsey’s thinking on how to structure effective global companies, and is now co-leading an effort to review McKinsey’s practical approach to organisation design. She works extensively with various clients in this area and in performance transformation. While working across industries, Roni has a special interest in advanced industries and technology. She holds a BSc from Tel Aviv University, and an MBA from INSEAD. Roni Katz is a partner in McKinsey’s London office.

References

1. McKinsey Globalization Survey of more than 300 executives, November 2011

2. Suzanne Heywood, Jessica Spungin, and David Turnbull, “Cracking the complexity code,” McKinsey Quarterly,May 2007.