By Charlie Colasurdo and Xiangming Chen

The self-evident USP of electric vehicles has, from the beginning, been their dramatically less-polluting effect compared with fossil-fuel vehicles. But, as Charlie Colasurdo and Xiangming Chen explain, case studies show that there is even more good news for those for whom mobility is crucial.

Electric micromobility is spreading globally, partly driven by China’s surge to become the global leader in its domestic adoption and the international production of electric vehicles, with BYD in pole position (Huang and Chen, 2025a). As this China-led e-micromobility leads to lower emissions, cleaner air, and quieter streets, where does it fit into the improvement of mobility networks in responding to traffic and transport demands posed by the rapidly growing and heavily congested megacities of the global South?

This article addresses this question by introducing a comparative study of two- and three-wheeler micromobility in Bangkok, Thailand, and major African cities. Across large cities in the global South, electric two- and three-wheelers have emerged as a major fleet in new mobility networks powered by inexpensive batteries, online applications, and economies shared by gig work and ride-sharing. They form a key cog of micromobility ecosystems that reflect the spatial arrangement and infrastructure of their respective urban environments.

Here, we take a comparative look at how electric motorbikes and tricycles have helped shape the mobility landscape of global-South megacities. While laying out the environmental, economic, and social benefits of this e-micromobility, we draw attention to the financing and the infrastructural and operational challenges facing the continued growth and smooth running of electric two- and three-wheelers.

Bangkok’s Burgeoning Transit Infrastructure

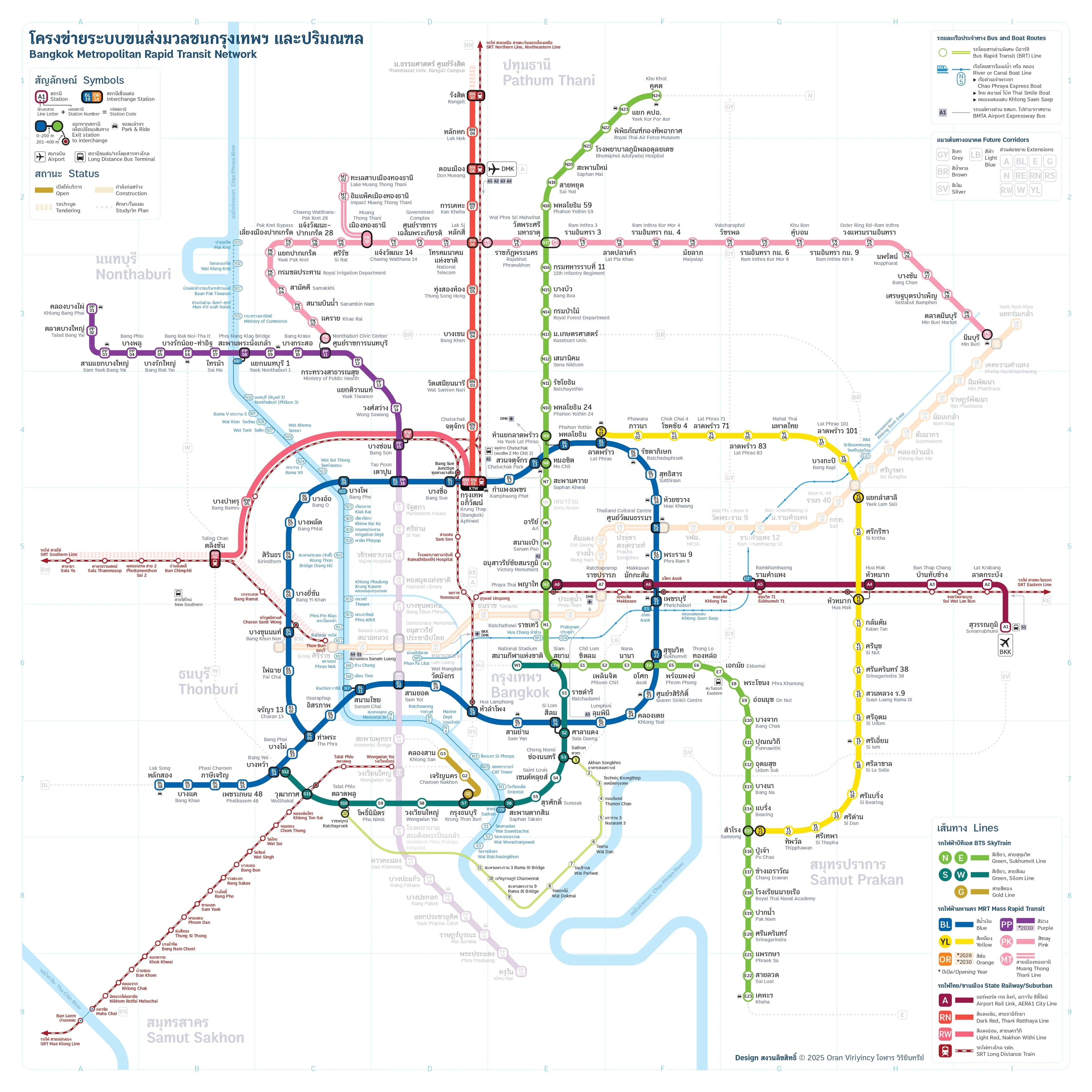

Bangkok, Thailand—a megacity of over 10 million people and one of the world’s most visited cities, with 32.4 million visitors in 2024—is famous for its clogged streets, facing acute challenges from congestion and particulate pollution (Mansel, 2024). To alleviate this, the city has invested heavily in a growing transit network. Since the launch of the elevated BTS SkyTrain in 1999, the city has been served by a system that has grown to encompass two electrified commuter rail lines, an airport rail link, two MRT lines, two monorails, three SkyTrain lines, and a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) line (Lesmes, 2018). More are on their way, including multiple high-speed rail lines connecting the city’s new central train station to Eastern and Northeastern Thailand, multiple line extensions, and a new MRT line under construction. The city’s 2024 mass rapid transit plan (M-MAP 2) calls for 11 new electric train routes covering 163 kilometers, with the first lines to be completed in 2018-29 (The Nation, 2024).

Expanding Bangkok’s rail system has connected heavily trafficked tourist destinations in the Phra Nakhon District (or “the Old Town”), suburban neighborhoods in Eastern and Northern Bangkok, and across the Chao Phraya River in Thonburi with the city’s Central Business District (CBD). As new areas fall into the catchment areas of transit systems, the first- and last-mile logistics become the next salient issue to address. Bangkok’s mobility ecosystem is a constellation of offerings, from motorbike taxis and the city’s iconic Tuk-Tuks to river ferries, canal and express boats, and buses. But users still face difficulties traveling the last mile from stations to apartments, offices, and schools, without adequate pedestrian infrastructure, and with extreme heat and a monsoon climate. Despite the increasing adoption of electric cars, trucks, and buses, the city is also facing an air pollution crisis that has shuttered schools and offices.

EV Tuk-Tuks as a new means of micromobility

A quiet, tech-enabled Tuk-Tuk revolution is unfolding on Bangkok’s crowded streets, leveraging innovative vehicle design, mobile app technology, and growing demand for last-mile mobility options.

The ubiquity of ride-hailing apps like Grab and Bolt, the rise of battery electric vehicles (BEVs), and the expansion of rapid transit have created a unique opportunity for micromobility solutions to disrupt the “last mile” challenge—connecting transit stations to homes, schools, and workplaces. In Bangkok, the city’s iconic petrol-powered Tuk-Tuks are now complemented by larger, quieter electric models run by MuvMi, a ride-hailing service operated with a mobile application similar to Grab. Hundreds of MuvMi Tuk-Tuks serve 11 Bangkok neighborhoods (photo 1), making thousands of trips in 2024. Now a constant presence at university campuses, metro stations, and in narrow alleyways, a quiet, tech-enabled Tuk-Tuk revolution is unfolding on Bangkok’s crowded streets, leveraging innovative vehicle design, mobile app technology, and growing demand for last-mile mobility options.

MuvMi’s parent company, Urban Mobility Tech Co. Ltd., was founded in 2016 by Krisada Kritayakirana, Pipat Tangsiripaisan, Supapong Kitiwattanasak, and Metha Jeeradit. It launched its MuvMi EV Tuk-Tuk app in 2018, with customers able to use an app to hail a custom-designed three-wheeler larger than the traditional petrol-powered Tuk-Tuk and able to seat six, including the driver. By 2022, MuvMi served approximately 2,000 to 4,000 passenger trips daily across five areas. In 2023, it had doubled to 10 service areas, and by 2024 served approximately 20,000 passenger trips daily. By October 2025, it had grown to 28,000 to 30,000 trips daily (Sangveraphunsiri, 2025).

A service area has coverage of approximately 100 to 150 square kilometers, with around 8,000 pick-up and drop-off “hop points” across Bangkok. Unlike a traditional Tuk-Tuk or ride-hailing trip, riders can only go between hop points within the same service area. Additionally, the service functions as a true ride-sharing program, which may travel to pick up other passengers along the way in a consolidated trip.

As of October 2025, MuvMi had approximately 700 active EV Tuk-Tuk drivers per day operating 600 to 700 EV Tuk-Tuks daily. The entire fleet is 800, but the rest of the vehicles are used to support the company’s other revenue streams, including private vehicle rentals (Sangveraphunsiri, 2025). Prices for MuvMi’s EV Tuk-Tuk ride share service are affordable, with fares beginning at 10 Thai Baht (0.32 USD)—in part subsidized by the company’s other ventures. This keeps the service competitive with motorbike taxis and traditional petrol-powered Tuk-Tuks, lowering the barrier to usage.

Adapting to a changing city

MuvMi reassesses its service areas every six months; the company’s operations team examines area maps and redraws borders to ensure that hop points in the vicinity of each area are included while placing more hop points on the borders of each zone to increase demand. As Bangkok expands the Metropolitan Rapid Transit (MRT) system, MuvMi is planning to focus on servicing stations as part of the high-capacity east-west MRT Orange Line (29 stations) and MRT Purple Line southern extension (17 stations), both targeted to open in 2030 (Sangveraphunsiri, 2025). MuvMi aims to fill in the service gaps of these lines, which will run through the heavily congested heart of the city. For newer monorail lines with lower capacity, including the Pink and Yellow Lines, the company is assessing demand for services along the routes.

MuvMi has likewise shaped the travel habits of its users; getting customers out of Grab cars and motorbike taxis and into EV Tuk-Tuks is the most challenging aspect of the service. The company’s marketing strategy has previously relied on word of mouth, and they are now partnering with the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration to support marketing campaigns about the city’s designated “car-free day” in September 2025, encouraging passengers located within MuvMi service areas to use MRT and BTS stations.

MuvMi’s typical user profile is a 20-40-year-old female office worker in the city center. Based on trip purposes, MuvMi has observed that 30-40 percent of its trips start or end at the metro station, showing that people largely use the trip for commuting and to transfer to mass transit (Sangveraphunsiri, 2025). For the other 60 percent of trips, many passengers chose MuvMi to go out for lunch or dinner, and within neighborhoods such as Ari, when passengers seek to travel to restaurants in a group setting where it’s a challenge to go without a car. MuvMi believes that about half of its current trips are to replace walking, motorbike or car taxis, and half are trips that previously did not exist and are made possible by its services.

Expansion beyond the primate city

Tuk-Tuks and other forms of micromobility are found across Thailand’s cities, including tourism hubs like Phuket and Chiang Mai. In 2019, Grab launched its GrabTukTuk Electric service in Chiang Mai in partnership with Nakorn Lanna Cooperative, with the goal of replacing 450 LPG-powered Tuk-Tuks (Karnjanatawe, 2019). Other companies making moves in the sector include the tourism-focused mobility service Lomo, which launched EV Tuk-Tuks via its LoMo platform in 2023, along with electric songthaews and motorbikes, with the goal of “100,000 download users in one year.”

MuvMi has decided not to expand its service to other cities using its own fleet, but is looking to partner with local operators to enhance their level of service and improve perceptions of public transport in other cities. In Chiang Mai, MuvMi is working to partner with songthaews to ensure that they survive financially, rather than the costly strategy of expanding its EV Tuk-Tuks to the city. MuvMi’s expansion to cities beyond Bangkok, limited as it has been thus far, points to the potential for electric Tuk-Tuks to become an economical and ecologically sound mode of multi-purpose micromobility in secondary Southeast Asian cities.

Electric Two-and Three-Wheelers in African Cities

As electric three-wheelers become popular in Bangkok and potentially in other Southeast Asian cities, both two- and three-wheeled motorcycles have emerged as a growing and more differentiated form of micromobility across a number of major African cities and even their rural hinterlands, with a prospect of further expansion. The recent growth of e-bikes, however, needs to be understood within the context and tradition of petrol motorbikes as a popular form of mobility in Africa over a much longer time. Motorbikes transport people privately. They carry people publicly as taxis. They have also become heavily used for moving goods and delivering food (see photo 2). In Kenya, for example, around five million people are reported to use motorbikes to make a living, or one in every 10 people (Huang, Lei and Ji, 2025).

Unlike in Bangkok, whose relatively well-developed public transit system relegates electric Tuk-Tuks to reach and cover peripheral areas, side streets, and “last mile” gaps, the limited scope and routing of public buses in most African cities, coupled with fewer paved roads, give motorbikes, including some three-wheelers, a more important role in transporting people and goods, especially access to city corners and across peri-urban areas, where informal transportation accounts for over 70 percent of commuting. In the major cities of Mali, Burkina Faso, and several other African countries, two- and three-wheelers make up nearly 80 percent of all vehicles. Petrol-powered three-wheelers account for roughly 80 percent of all short-distance hauling (CIEG, 2025).

Where does China fit in?

Since China has been Africa’s largest trading partner since 2009, it was to be expected that Africa’s large motorcycle market would attract a lot of imports from Chinese manufacturers. In fact, in 2024, China sent 3.8 million fully assembled motorcycles to Africa, worth $282 million, a 21 percent increase year on year (Huang, Lei and Ji, 2025). In the first quarter of 2025, China exported 1.2 million motorcycles to Africa, its second-largest market in the world, a 63 percent increase over the same period of 2024 (China Industry Net, 2025). The Chinese megacity of Chongqing stands out as the largest source of China’s motorcycle exports to Africa. In 2024, its motorcycle exports to Africa amounted to $361 million, up 19.7 percent year on year, accounting for 15-20 percent of all China’s exports of motorcycles to Africa (Wang, 2025).

Of all Chinese motorcycle exports to Africa, electric two- and three-wheelers have gained share due to their growing benefits on African roads. First of all, traditional petrol-powered two- and three-wheelers are a major source of street-level pollution. In Nairobi, tailpipe emissions, much of which come from motorbikes, account for 40 percent of the city’s overall pollution. Second, electric three-wheelers in Tanzania can lower the fuel costs of petrol-powered three-wheelers by one-sixth, given the high and frequently increasing petrol prices. It allows someone who has switched to an electric three-wheeler to reduce their daily delivery cost from $12 to $1 a day (CIEG, 2025).

Chinese tech for African e-micromobility

Building on the growing appeal of electric two- and three-wheelers to African consumers, Chinese companies have introduced some technological improvements to better suit the African conditions of accelerated urbanization, traffic congestion, inferior roads, and severely lacking “last mile” connectivity. A Chinese tire company in Chongqing supplying local motorcycle exports to Africa and leveraging its products built to suit the mountainous megacity has designed a series of new products to withstand contact with African road conditions like rough surfaces, potholes and objects, and high heat. The company has also planned to strike long-term contracts with African importers of motorcycle tires.

To best illustrate the growing role of Chinese tech firms in Africa’s e-micromobility, we turn to TECNO, a subsidiary of Transsion, a Chinese manufacturer of mobile phones headquartered in Shenzhen, also known as China’s “Silicon Valley” of hardware. Having focused primarily on Africa since 2008, TECNO now dominates, with over 50 percent of Africa’s mobile phone market. In 2023, TECNO unveiled its first three-wheeler, branded TankVolt, and quickly added other models of electric two- and three-wheelers.

In addition, TECNO has offered economical models starting as low as $420 per vehicle under the new and related brand of REVOO. This market-entry strategy, which duplicates TECNO’s very low-cost mobile phones at the early stage of its entry into Africa, has helped secure a large order of 5,000 three-wheelers from the Nigerian government and pushed TankVolt into the top EV sellers in Africa (CIEG, 2025). Most importantly, TECNO has introduced BaaS (battery-as-a-service), which allows someone to buy an EV or electric motorbike without the battery and instead subscribe to it separately, as a way of significantly lowering the initial cost of purchase.

Adaptation and extension

The Chinese involvement in Africa’s e-micromobility has fueled its broader expansion, which in turn has created opportunities for indigenous African companies to emerge as both competitive and complementary players. Founded in 2019, with its operational center based in Kenya, Spiro in 2022 signed a major contract to import 50,000 electric motorbikes from Hangzhou, China. In 2023, Spiro raised $63 million via loans from Société Générale (SG) in France and GuarantCo in the United Kingdom to build battery-switching stations for the BaaS, accompanied by fleet expansion in Kenya and Uganda. With a loan of $50 million from the African Import/Export Bank in 2024, Spiro expanded into Cameroon and Morocco, and into Tanzania in 2025, when it also raised $100 million more from the capital markets for further growth (Tailun, 2025).

Chinese involvement in Africa’s e-micromobility has fueled its broader expansion, which in turn has created opportunities for indigenous African companies.

Spiro’s success rides on its BaaS. Its CEO remarked, “African riders typically drive 10-12 hours and cover 150-200 kilometers per day. While they save a lot of money using e-motorcycles, they can’t afford to stop to charge the batteries.” Since batteries account for 30-40 percent of the EV cost, most African buyers can’t afford electric motorcycles with batteries. Spiro’s solution is a battery-subscription system, which allows drivers to pay for daily usage (Tailun, 2025). In Kampala, Uganda, an e-motorcycle driver switches a low or drained battery for a fully charged one by paying a small and varied fee, often on his TECNO phone. Battery-swapping stations in Kampala have also attracted e-motorcycle drivers for the popular boda-boda taxis, even though electric motorcycles account for only about 10 percent of the city’s taxi fleet. If more e-motorbikes for different uses continue to grow, they will help reduce carbon emissions in one of the most polluted cities in Africa.

As an integral part of its business model, Spiro has established assembly plants in Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, and Nigeria, where CKDs or fully disassembled kits from China are put together. Spiro’s Kenya-based core plant can now make the traction motor, a key part of an electric motorcycle. Of all the plastics parts, helmets, and brake components, the locally sourced portion has already reached 30-40 percent, which is expected to rise to 70 percent in two years (Tailun, 2025). This level of localization would not be possible without Spiro’s collaboration with Chinese companies to gain production knowledge and technology transfer.

Conclusion

Across Southeast Asia and Africa, EV micromobility companies have leveraged increased access to smartphones and electric vehicle battery technology to address diverse transportation needs. In Bangkok, a robust public transit network has facilitated the parallel development of last-mile EV Tuk-Tuk rideshare, which can be flexibly designed to adapt to commuter demand. In African cities, EV motorbikes have shifted into high gear across varied lanes of usage ranging from public transport to short haul to service delivery. They fill larger address gaps in public transit, getting people around and beyond the simultaneously congested and sprawling African cities. In addition, while China is substantially involved in Thailand’s EV sector, featuring BYD’s large factory near Bangkok (Huang and Chen, 2025b), smaller Chinese companies have been actively involved in Africa’s market for electric motorcycles through exporting completed vehicles, supplying CKDs, establishing local production, and promoting technology transfer.

Both case studies illustrate some tangible economic and social benefits of EV micromobility services, including reducing fuel expenses, lowering urban pollution, and allowing riders to make quick and convenient trips that were otherwise impossible with existing mobility options. In hot, congested, and rapidly growing urban areas in Southeast Asia and Africa, where many travel by two- and three-wheelers, EV micromobility has generated substantial early gains for quality of life among its uses while heralding an important pathway to more electrification and decarbonization broadly. It holds promise for the future.