Does your board have the right information for decision making? Better decision making has been a growing demand at any organizational level, but is crucial within corporate governance arenas. The best board dynamics and focus on substantive business issues do not ensure effective boards’ decision making. Better decision making depends on information quality and availability.

Better information does not show up on its own, but depends on carefully designed information architectures. Relying on solid information sources fosters awareness and lies the grounds for better information architectures, so directors can do their job in a more effective and efficient way. What, why, how and where questions shall be raised in order to attain such paradigm, and the pillars for such arrangement shall be laid down, by means of an adequate information architecture. Therefore, some clarity and thinking behind such information architecture design deserve attention.

Introduction

Long is gone the time of the rubber stamp boards. The current pandemic age has no space for amateur boards. Boards need to ensure their decision-making processes and dynamics are robust. Beyond the need to become better at monitoring, boards need to become better at strategic decision making. Besides a proper process, good decision-making depends on information quality and an effective and efficient supporting information architecture at the board level.

Without such information architecture in place, the board might not have it clear when to lead, when to partner with management, or when to keep out of the way. Cases of bad or suboptimal corporate governance legitimate the need to dedicate some attention to such subject, making it critical for boards effectiveness. Moreover, such information architecture does not have to be complex.

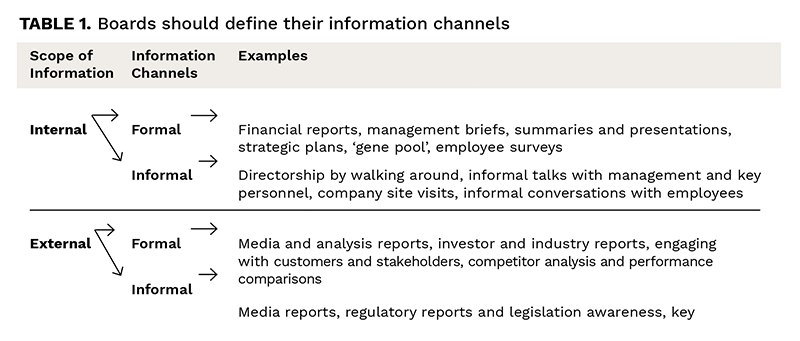

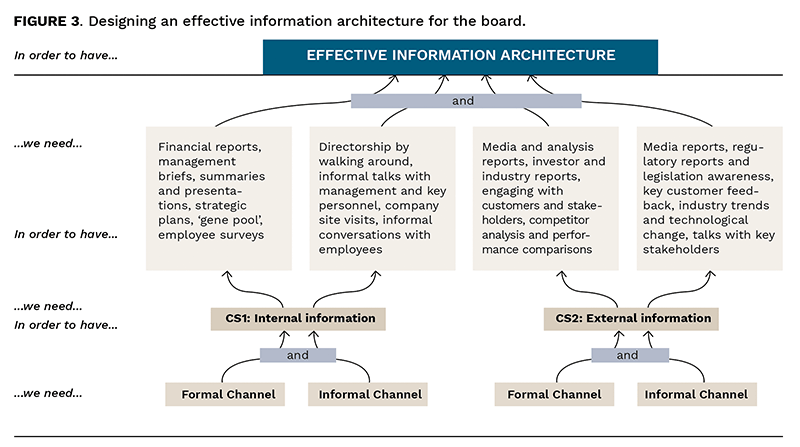

To improve the effectiveness of boards in accomplishing their duties to the organizations they serve, attention shall be placed on information architecture, comprising both formal as well as informal channels, encompassing both short-term and long-term strategic issues. Formal channels are designed. Conversely informal channels are typically more subtle and imply conquering peoples’ trust, including both company executives and the workforce.

Moreover, to address the demands of the post pandemic recovery, effective corporate governance need boards to dedicate attention both to internal as well as external information relevant for the organization. Board’s scope of accountabilities has been growing as shown by the increasing need for specialized committees, from risk, strategy, sustainability, among others [1]. Such specialized committees demand distinct information channels and there is not such a thing as “one size fits all” solution.

Let us look into some background and the design of and adequate information architecture for effective boards of directors’ effectiveness.

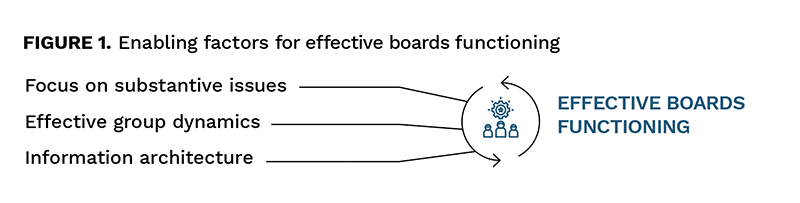

Enabling effectiveness at the board

Some corporate governance authors have been calling attention to a few Critical Success Factors (CSF) for effective board functioning. Three main enablers of effective boards functioning are (Figure 1): (1) focus on substantive issues, (2) group dynamics, and (3) adequate information architecture.

Effective boards focus on substantive issues, addressing the right issues concerning the short- and long-term strategic issues which face the businesses they are responsible for, ensuring that they differentiate between doing the things right versus doing the right things.

Good group dynamics plays a critical role in interactions between boards and management, alongside the dynamics among board directors themselves.

How boards acquire the relevant information and in what form is critical for their modus operandi. Regardless of board dynamics and the focus on substantive issues that may affect the business, if boards do not have the right information available, their efforts may end up being worthless or at least ineffective. Hence, an effective Information architecture is of utmost importance in supporting effective corporate governance.

Having these three enabling factors, or critical success factors under control is a necessary condition for board effectiveness. Without them, boards may become ineffective, if not difunctional.

The unfamiliar with typical boards operation, might sometimes find it as a sort of millieu where influence moves and sometimes sinister characters operate. It may well be like that in some cases, and such may be the case in a number of businesses and geographies. The demands of the XXI century corporate governance standards, aggravated by the current pandemic paradigm, have no place, however, for such amateur approaches.

In designing an adequate information architecture for boards, a first step may be to clarify the applicable taxonomy.

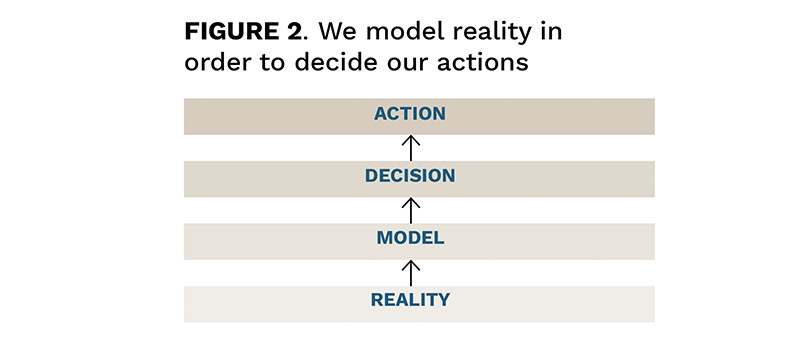

Regardless of their roles, people address the future of their organizations by modelling the reality in order to decide their actions (Figure 2).

However, acquiring the relevant aspects from reality into a model that supports decision making involves data, information, knowledge, and some would add wisdom. Being the decision-making process a function of such models together with the quality and availability of relevant information, it is critical to decide which types of information are relevant, why, how and when.

Information channels and architecture

For effective performance boards need information, both internal and external to the businesses they are accountable for. Moreover, information may be formal or informal. Information that come from formal communication channels designed by the board or by the board in conjunction with management, are considered formal. For effectiveness purposes, however, boards also need to rely on information that comes from informal channels, oftentimes ad-hoc contacts with management, or information that are obtained just by “walking around”, which entails visits to the company plants and operating facilities, where boards may be engaging informally with management and even the workforce. Such informal channels are critical for board directors to avoid falling victims of information filters – as regardless of how performing a managing director and his/her executive team might be, boards will always get filtered information.

As an interesting example, Soichiro Honda, Honda Motor Company founder was known by wearing blue-collar clothes when visiting Honda plants, where the workforce would feel at ease to speak freely, therefore sharing valuable pieces of information with him [2]. Actually, part of the workforce across such giant manufacturer would not even recognize the ‘big boss’. A similar example comes from Konosuke Matsushita and the way he used to interrelate with his workforce across many of his companies’ operations, and where the same pattern of informality would provide this top leader with the highest quality and unfiltered information, while at the same time motivating the workforce due to his amicable style. At his early times as the company’s top leader, Matsushita even used to do picnics with his workforce [3]. Such are excellent examples of informal communication channels that may feed high quality information into the top of organizations, alongside the attention to the human side of information gathering, suggesting some relevant lessons to be taken from these founders of modern Japan in what corporate governance concerns.

For business and global economies to recover from the current pandemic stage, good corporate governance will surely demand more attention to factors like information flows across and into companies.

Balanced Scorecards (BSC) are normally used by management for controlling purposes, however, such tools may play a further strategic role if designed to serve boards of directors in improving their decision-making processes [4]. Perhaps better than the standard BSC, would be to look into the older Tableau de Bord, originally from France, which differently from the former offers a more strategic view on the organization. It is actually a happy coincidence that such scorecards were named as Bord.

A good information architecture needs board directors to pay attention to internal issues as well as external ones. Internal information, originated by management, reach the board as briefs and summaries, prioritizing issues according to their strategic relevance, sometimes suggesting a set of actions [5]. Such approach is necessary, however not sufficient. Boards also need to be aware of the external context surrounding the organizations they serve, understanding the business’s customers, the competitive landscape, mapping diverse stakeholders’ concerns, assessing technological risks among other strategic issues. Moreover, boards need both formal and informal information channels. The former comprising for example, CEO reports, financial status reports and forecasts. The informal information channels may range from engaging with peer directors on a case-by-case basis, to getting in touch with management and the workforce. Having lunches and coffees with key personnel should never be overlooked, as it is an excellent way of gaining awareness about relevant business issues. Obviously, such shall be done within the right balance. Directors should also ensure they get as much information from independent sources, in order to avoid ‘blind spots’, while preventing the bias from management frames. Boards shall be proactive in designing their specific information needs, to ensure their jobs are done effectively, while at the same time avoiding the pitfall of excessive information that may result in dysfunctionality and suboptimal performance.

Information architecture needs to be backed by some cause-and-effect logic, structuring the desired information system though a set of logical relationships.

Figure 3 suggests a logical structure showing the necessary – oftentimes necessary and sufficient – conditions in order to shape a desired information architecture for the board.

Summarizing

Board of directors’ roles spill over the purely commercial corporation. Hence, one may find boards in non-profit organizations, public services, or even academy. What is common, however, to all of them is that effective boards need to ensure they focus on substantive issues have the right group dynamics, and have an adequate information architecture. None of these enabling conditions is sufficient on its own. All are needed for effective corporate governance. Information architecture is a necessary condition for good board performance, and information scope matters in making boards aware of internal as well as external conditions potentially impacting the organizations they serve. Information channelled into the board by the CEO is always subject to some filtering, and enabling potential blind spots. Hence boards shall establish both formal and informal information channels in order to ensure they have the adequate information to feed their decision-making process. While the formal communication channels may be designed jointly with management, the informal communication channels are usually put in place by the board directors themselves, sometimes in an ad-hoc fashion which may demand informality in approaching specific company managers and the workforce. To recover from the state induced by the global pandemic, board directors will need to be proactive in ensuring that they have their information needs covered, for maximum performance and acting under the finest ethical standards.

This article was originally published on 10 September 2021.

About the Author

Pedro B. Agua is a Weapons and Electronics Engineer, and currently a Professor of General Management at the Portuguese Naval Academy and Senior Teaching Fellow at AESE Business School in Lisbon. Professor Agua has authored many articles and book chapters featuring various systems and business policy subjects. He combines his teaching profile with an extensive business background of more than 27 years dedicated to cutting edge industries like defence, telecommunications and subsea engineering. Pedro holds a Ph.D. in Engineering and Management awarded by the University of Lisbon.

References

- [1] Ormazabal, G. (2016). Risk oversight: What every director should know. IESEInsight, issue 28 1st Quarter.

- [2] Derisbourg, Y. (1993). Monsieur Honda. Paris: Editions Robert Laffont.

- [3] Kotter, J.P. (1997). Matsushita Leadership. Lessons from the 20Th Century Most Remarkable Entrepreneur. New York: Free Press.

- [4] Kaplan, R. S., & Nagel, M. E. (2003). Improving Corporate Governance with the Balanced Scorecard. HBS Working paper Series.

- [5] Nueno, P. (2016). 10 trends for the board of 2020: The future of governance. IESE Insight, 29, 45-51.