By Janis Forman

Taken from chapter 2 of Storytelling in Business: The Authentic and Fluent Organization, this excerpt focuses on the importance of authenticity, the foundational element of the book’s research-driven framework for organizational storytelling. The book then takes up the additional elements of storytelling in business and uses original cases from Chevron, FedEx, Phillips, and Schering-Plough to show how companies can engage in storytelling to make sense of strategy and develop or strengthen culture and brand.

How can we think systematically about organizational storytelling? What are its key components and the relationships among them that apply across the companies that represent best practices? The research for this book began without a preconceived framework for making sense of organizational storytelling. The framework that emerged is based on analysis and primary research, including multiple site visits to best practices companies, interviews with more than 140 professionals who have expertise in organizational storytelling and review of the relevant company documents and literature in several fields.

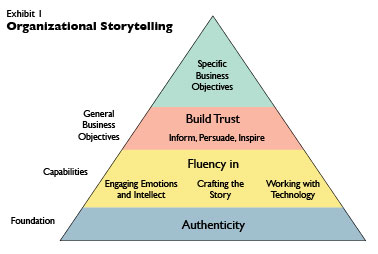

Presented here, the framework identifies key components of organizational storytelling that come into play across the living cases of Schering-Plough, Chevron, FedEx, and Philips, which, in turn, elaborate on the framework’s components as they apply to a greater or lesser extent to the particular case.1 Moving forward, organizations and individuals that want to build storytelling capabilities can use the framework to guide and assess their efforts. This chapter, then, presents the framework, its key components and the relationships among them. (See exhibit 1)

Successful storytelling for business is authentic and fluent. At its foundation, organizational storytelling should be authentic—credible, realistic, tangible and intended to be truthful. It should also be fluent. Storytelling should draw the attention of stakeholders by engaging their emotions and intellect, using the craft that makes this form of communication compelling, and, in some instances, using technology, anything from photographs to state-of-the-art social media. These storytelling capabilities taken as a whole—the ability to engage the emotions and intellect, to use the craft of storytelling, and, in some instances, to work with technology—characterize fluent storytelling.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Stories for business have practical purpose. This is, in general, to gain or strengthen the trust of the intended audience(s), and, with this achieved, to inform, persuade, and even inspire. In addition to achieving these general business objectives, stories are intended to accomplish specific business objectives. These objectives can cover a range of things, anything from recruiting new members to a firm to increasing the customer base to presenting a profile of the senior leadership to the media. In the best practices cases, these specific business objectives include the quite significant objectives of building and strengthening corporate strategy, corporate culture, and corporate branding, with the ultimate goal of building the business, its profits and reputation. Let’s take up each of these components beginning with authenticity, the foundation of organizational storytelling.

Authenticity in Storytelling for Business

“Authenticity is a rule any good communicator should follow. Don’t put out a persona or a group of facts you don’t have. Don’t lie. Everything that is knowable will ultimately be known.” Dick Parsons, Chairman of the Board, Citigroup, and former Chief Executive Officer, AOL Time Warner.2

According to the many experts in organizational storytelling interviewed for the book, the dictum “Words—in this case, stories–must match deeds” is the key ethical criterion by which stories should be judged. Does the story pass the test of being “credible, “realistic,” “tangible”—descriptions that come up repeatedly in discussions of organizational storytelling at best practices firms? If not true now, is the story (or stories) realistically aspirational? Does it support the organization’s strategy, culture and brand? In addition, stories should not be a monolithic expression of the organization’s leadership; rather, they should take into account the voices of significant others, such as employees, customers, and communities.

Words Must Match Deeds

Tell the truth. Let the public know what’s happening and provide an accurate picture of the company’s character, ideals, and practices.

Prove it with action. Public perception of an organization is determined 90 percent by what it does and ten percent by what it says. Principles of the Arthur W. Page Society.3

“Truth will come to light in the end truth will out.” Shakespeare’s “Merchant of Venice” 2.276,77.

In 2007, the Arthur W. Page Society, a group of senior corporate communication professionals, published a study introducing the importance of “authenticity” as a guiding principle for companies as they respond to the current business environment, characterized as a “global playing field of unprecedented transparency and radically democratized access to information production, dissemination, and consumption.”4 This environment, they argue, establishes “authenticity” as a requirement for businesses to succeed, an ethical concept that depends on the first of two Page Principles that also steer this professional association’s work and its understanding of corporate identity, “tell the truth” and “prove it with action”:

In such an environment, the corporation that wants to establish a distinctive brand and achieve long-term success must, more than ever before, be grounded in a sure sense of what defines it—why it exists, what it stands for and what differentiates it in a marketplace of customers, investors, and workers.

In a word, authenticity [emphasis in the original] will be the coin of the realm for successful corporations and for those who lead them.5

In the wake of highly publicized corporate scandals at Enron and Worldcom, Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme, and the BP oil spill in the Gulf—among other crises–there’s been a persistent call for honesty in business leaders and for accountability in their actions and those of the organizations they lead.6

Regardless of the specific business objective of an organizational story, the teller needs to give scrupulous attention to the accuracy of the story’s details. This is especially the case because “story” as a kind of business discourse is often greeted with scepticism: As one executive I taught in a storytelling workshop remarked, “By stories, don’t you mean fairy tales? Aren’t you talking about fantasy?” His comment is fairly routine.

Authentic storytelling about an organization is, then, data-based storytelling. The story’s details as well as those in the documents that often serve as a companion piece to the story are “fact-based and fact-checked,”7 explains Helen Clark, Manager, Corporate Marketing, Policy, Government and Public Affairs, Chevron. Data need to be verified using multiple sources. “There’s a need for evidence-based messages,” asserts Jeff Hunt, Principal and Co-Founder of Pulsepoint Group, “so collect and use the stories of customers and their experience with the company.”8 In a similar vein, Karen Everett, a documentary story consultant, points out that “facts are the ballast—they give stability—and the constraint or burden [in creating documentaries as opposed to a work of fiction]. You can’t create facts or scenes to help you with the story line. We who deal with real life can’t make up scenes.”9 Using reliable data forms the basis for the integrity of organizational stories.

Not only do stories embed facts, but they also work in tandem with other corporate communications, the primary purpose of which is to provide data, such as product specs or explanations of policy or technology. A drug to fight cancer produced by Schering-Plough is featured in a story told by a cancer survivor, and the product’s description is also made available to interested parties. A fact sheet on geothermal energy at Chevron is supported by stories that bring the technology down to human scale and make it tangible. A story by a FedEx manager about growing up in Asia, which occurred during a period of unprecedent growth in trade there, is accompanied by data about the company’s cargo delivery to these regions. A story about Philips’ work in LED-based lighting design for a city center is supplemented by facts about the technology, urban crime, and city festivals that are enhanced by creative lighting.

The big exception to this requirement of fact-checking is authentic autobiographical storytelling for business, what I call a professional’s signature story, for which heart-felt conviction and fidelity to feelings can trump accuracy of detail. This distinction will be discussed in the last chapter of the book.

The Voices of Significant Others

Authentic storytelling should take into account the voices of significant others, such as employees, customers, and communities and give room for their stories. Never just about the organization alone, the story is open to the needs, concerns, knowledge, values, and interests—and even the voices—of others. This requires the storyteller, whether an individual or an organization, to begin the activity by listening.

As a listening storyteller,10 an organization’s representatives may invite end users of its products and services to tell their stories; give a place for these stories in written, on-line and oral communications; and acknowledge the stories of what branding expert Rohit Bhargava calls “accidental spokespeople”—those who are not authorized to speak about its brands but, nonetheless, express their opinions.11 The CEO of Schering-Plough goes on a listening campaign to learn about employees’ concerns about changes in strategy, incorporates their voices in his story of the firm, and knows, as a result of his “listening” campaign how to adjust his story to their needs and concerns. Chevron gives room on its Web site for partners and collaborators to tell their stories about their involvement with the company. FedEx opens up company blogs to interested outside parties to tell their stories about topics like work/life balance or sustainability. Philips invites patients and healthcare experts to storytelling workshops to help their employees understand these outsiders’ stories and, in doing so, to improve their own. As one workshop participant noted: “To speak authentically, Philips’ employees need a chance to hear the language of people-centric healthcare first-hand and interact with those on the frontline.”

For stories to be genuine in an organizational setting requires companies to include the multiple personal voices and interpretations of employees, customers and others who tell stories about their experience of and with the organization.12 For example, at Schering-Plough, this can mean a researcher linking his passion for medical research to the organizational goals of drug discovery; at Chevron, an employee taking into account the company’s norms about “corporate voice” while expressing his unique experience of educating the next generation of scientists; at FedEx, an employee talking about her personality, in the form of dance and discussion on a videoclip available on the company Web site and on the employee’s Facebook, while linking this digital story to the value the company places on extraordinary effort; at Philips, an employee or customer expressing a personal, emotionally compelling experience with light and connecting this story to the organization’s brand and business concept.

The balancing act between the personal and the organizational in which the aims of each party, the individual and the organization, is respected can be quite challenging. Organizations have been successful in achieving the balance by using some combination of instruction and guidelines for storytelling that, on the one hand, encourage an employee’s self-expression and individual ownership of a story, and, on the other, identify specific topics that the organization wants to see communicated, for instance, strategy, culture, or branding.13

Fluency in Storytelling For Business

Being authentic is a necessary, though not a sufficient, condition for successful organizational stories. Storytellers need to be fluent as well to cut through the busyness, distractions, and competing demands of work life. Stories, then, need to engage people’s emotions and intellect, live vividly in their memory and imagination, and move them to respond in ways the storyteller intends. To be fluent, an organization’s spokespeople need competence in the craft of storytelling and, in some cases, in the use of communications technology. As we’ll see in later chapters, best practices companies may provide workshops, guidelines, and expert help to assist employees in developing these capabilities.

General Business Objectives: Build Trust, Inform, Persuade, Inspire

Unlike most personal stories, film, and literature, organizational stories have business objectives. These include building trust in the organization, an objective that depends on the story’s authenticity and fluency. Once trust is achieved, a company’s stories are on the way to achieving the general objectives of informing, persuading, and even inspiring or some combination of these objectives.

Reprinted by permission of Stanford University Press Excerpted from Storytelling in Business: The Authentic and Fluent Organization by Janis Forman. Copyright 2013. All rights reserved.

About the Author

Janis Forman, founder and Director of the Management Communication Program at the UCLA Anderson School of Management, consults internationally on storytelling for business. With Paul Argenti, she is author of The Power of Corporate Communication, winner of the Distinguished Publication Award, the Association for Business Communication.

References

1. For instance, technology has a minor role in the Schering-Plough as well as in the Philips case, but has great importance to the Chevron and FedEx cases. Storytelling and strategy is central to the Schering-Plough and Philips cases but not to the FedEx case.

2. Dick Parsons Presentation, “CEO and Media Exchange: Lessons Learned in Trying Times,” Arthur W. Page Society Spring Conference, New York City, April 7, 2011.

3. “The Page Principles,” (2011), http://www.awpagesociety.com/about/the-page-principles/ (accessed October 8, 2011).

4. Arthur W. Page Society, “The Authentic Enterprise,” 2007, 6.

5. Ibid., 16.

6. By and large, I avoid the word “transparency,” which is often used to mean complete disclosure or honesty, because I find it to be problematic. In literal terms, “transparency” means that company insiders and outsiders alike are provided with a window to see every aspect of a business, but companies should not—and do not– reveal everything. Just consider the consequences to their competitive positioning were they to reveal their trade secrets or strategies and tactics for building market position.

7. Interview with Helen Clark, January 21, 2009.

8. Interview with Jeff Hunt, Mary 12, 2010.

9. Interview with Karen Everett, June 23, 2010.

10. See discussion on this topic in Janis Forman, “Leaders as Storytellers: Finding Waldo,” Business Communication Quarterly, September 2007, 371.

11. In Personality not included: Why Companies Lose Their Authenticity—and How Great Brands Get It Back (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008), Rohit Bhargava explains that “accidental spokespeople” are those stakeholders who are “not controlled by the brands they describe, but . . . influence the perception about those brands in a powerful way.” (P. 56).

12. In “Building Trust in Times of Crisis: Storytelling and Change Communication in an Airline Company,” Corporate Communications 11 (4) (2006), Roy Langer Roy and Signe Thorup talk about the metaphor of the organization as an orchestra in their summary of research on organizational change: “. . . organisational change communication can be seen as a polyphonic orchestration of an organisation’s many voices. Rather than seeing an organisation as a single body with a single (management) voice telling the grand story, it should be regarded as an orchestra consisting of many different instruments and voices, each capable of performing in its own register and each with its own distinctive sound. All the different instruments and voices enable an organisation to play more than one tune. An orchestra consisting only of drums may be able to produce a certain noise, as long as everyone can be persuaded to play in the same rhythm.

In a polyphonic perspective, communication management focuses on facilitating and coordinating all the voices of the orchestra with a view to creating polyphonic harmony, allowing space for the special qualities of each voice or instrument. This presupposes that there is enough space for each individual and for individual differences—including space for solo parts or local articulation. This presupposes that each voice is heard, making it possible to identify what it is capable of and what it wishes to contribute. The conductor of the orchestra (the management) does not use his baton to decide what should be played and how.” (P. 375).

13. See especially the cases on Chevron, pp.000, and on FedEx, pp. 000.