By Adrian Furnham

Is the world a just place – or just a place? Then again, should we just pessimistically expect the unjust and so avoid disappointment? As Adrian Furnham explains, a little bit of faith in the ultimate fairness of it all could be your best armour against the arrows of outrageous fortune.

- Fairness is man’s ability to rise above his prejudices. – Wes Fessler

- Win or lose, do it fairly. – Knute Rockne

- Be fair. Treat the other man as you would be treated. – Everett W. Lord

- Justice is a certain rectitude of mind whereby a man does what he ought to do in circumstances confronting him. – Saint Thomas Aquinas

- Nothing can be truly great which is not right. – Samuel Johnson

- It is not fair to ask of others what you are unwilling to do yourself. – Eleanor Roosevelt

- Fairness is what justice really is. – Potter Stewart

- These men ask for just the same thing, fairness, and fairness only. This, so far as in my power, they, and all others, shall have. – Abraham Lincoln

- Though force can protect in emergency, only justice, fairness, consideration and cooperation can finally lead men to the dawn of eternal peace. – President Dwight Eisenhower

- Expecting the world to treat you fairly because you are a good person is a little like expecting the bull not to attack you because you are a vegetarian. – Dennis Wholey

- In our hearts and in our laws, we must treat all our people with fairness and dignity, regardless of their race, religion, gender or sexual orientation. – President Bill Clinton

- Live so that when your children think of fairness and integrity, they think of you. – H. Jackson Brown, Jr.

Count the use of the “F-word” in politicians’ speeches: yes, Fair. Many believe that if you appeal to a voter’s sense of fairness, you can simultaneously provoke enough positive and negative emotions to secure a vote for their party position. We all want to be fairly treated and live in a just world. But can we agree on the what is fair and unfair, just and unjust? And how do people react differently to lack of justice?

Different Perspectives

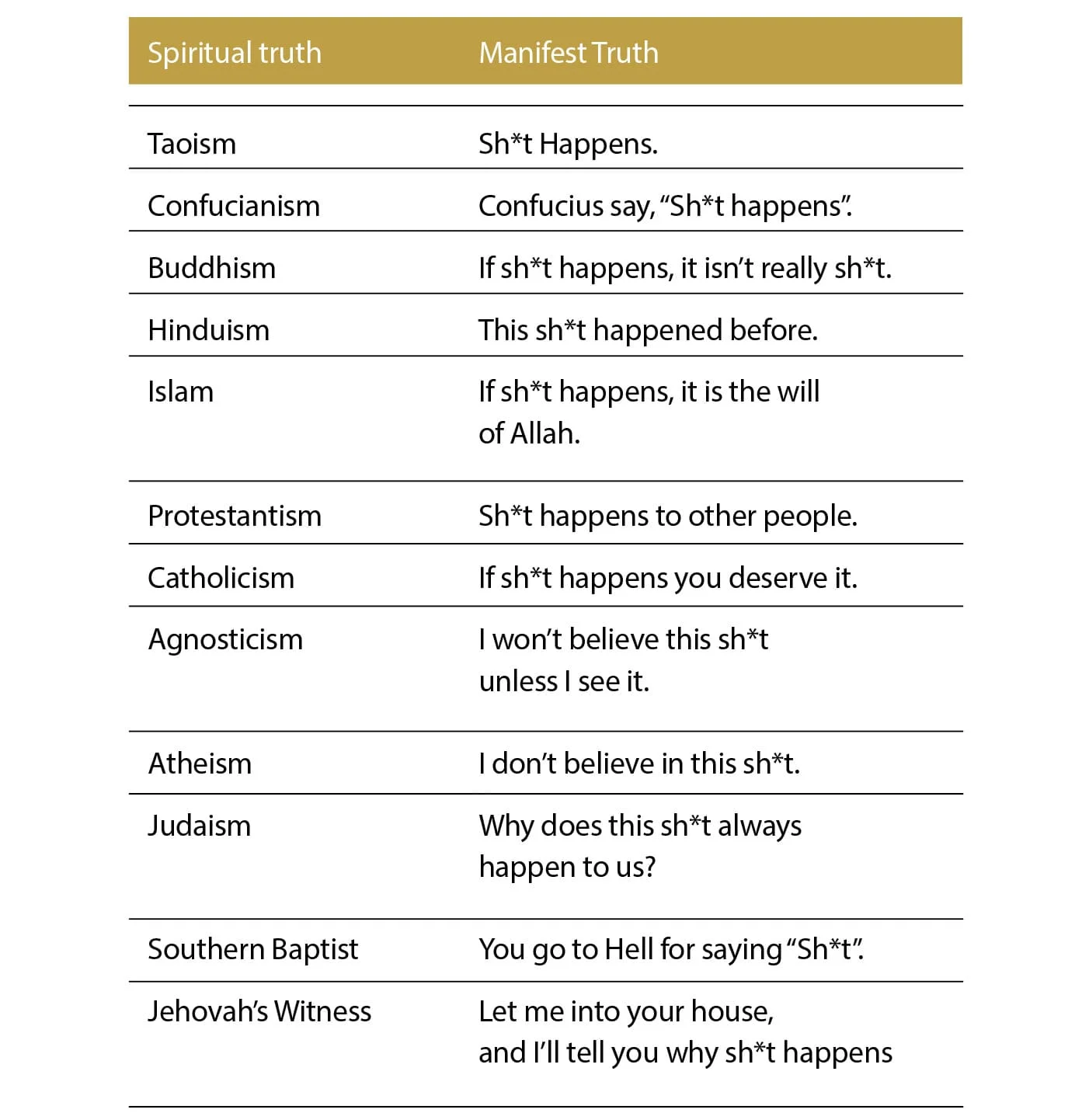

There are clearly many very different understandings of why there is such manifest and obvious injustice and unfairness in the world.

Ellenbogen (1986), in a very memorable and humorous way, distinguished between how different religions understand injustice. These are rather simple-minded stereotypes, and possibly even “offensive” to certain groups, because of the way they try to encapsulate and distinguish between various conceptualisations of injustice. It illustrates forcefully some of the numerous and profound differences in the ways injustice / evil / sh*t is considered.

It is clear that injustice, here described as “sh*t happens”, is an extremely important issue and that many struggle for an explanation for its existence, but also how to cope with it. It is very big topic indeed. The fundamental “take-away” is to take a much wider view. All peoples have had to confront injustice and explain why it occurs.

The moral of the story? There are clearly many very different understandings of why there is such manifest and obvious injustice and unfairness in the world … and therefore of how you should try to confront and ameliorate it.

Equity and Justice Sensitivity

There are clearly individual differences in the extent to which people are sensitive to events: that are fair, just, and right or the opposite. There are two psychological constructs in this area: the older construct of equity sensitivity and the newer construct of justice sensitivity. The focus of equity sensitivity is on the outcome of an allocation, which limits the construct to distributive justice.

The focus of justice sensitivity is on the role a person can play in any incidence of injustice. A person can be the victim of injustice (victim sensitivity), the observer of injustice (observer sensitivity), the beneficiary of injustice (beneficiary sensitivity), and the perpetrator of injustice (perpetrator sensitivity). Thus, the concept of justice is not limited to distributive justice in the justice sensitivity construct, but includes all kinds of injustice (distributive, procedural, retributive, restorative, interactive, legal).

Researchers have determined three different types of justice-sensitive people: benevolents, equity sensitives, and entitleds. Benevolents are referred to as “givers”, because they are willing to bestow as much as possible on people and organizations but are relatively unaffected by unfair treatment. They are prepared to experience personal discrimination, unfairness, and injustice for a variety of personal reasons, and unlikely to complain or attempt some recompense. Some religions would strongly approve of this behaviour, which is self-sacrificial for the greater good.

The counterparts are entitleds, who are also labeled “takers”. Their ultimate ambition is to maximize their outcomes. They appear selfish, egocentric, and deeply concerned about getting what they can from others. In between, there are “equity sensitives”, who seek to achieve a balance between input and outcome.

As these different categorizations suggest, there are systematic and predictable behavioral differences between the three types. Benevolents are more likely to tolerate unfair payment, whereas entitleds are more likely to react more strongly than benevolents to pay inequities by reducing their job performance. There are interesting questions about the development of justice sensitivity and how it can be appropriately moderated.

Another important difference is the assumed dimensionality. The justice sensitivity construct conceptualizes all facets (victim, observer, beneficiary, perpetrator) as potentially independent components (a person can be victim sensitive and beneficiary sensitive). By contrast, equity sensitivity is a one-dimensional construct (a benevolent person cannot be entitled). These differences have important implications for measurement and research on developmental origins, behavioral outcomes, and correlations (with personality traits, for example).

Justice sensitivity research has shown that all facets have some uniqueness, which means that they overlap only partially and that they have unique relations with other variables. Yet all studies show a systematic pattern of overlap among the facets. Observer, beneficiary, and perpetrator sensitivity correlate highly among each other and seem to reflect a genuine concern for justice for others. Victim sensitivity correlates only moderately with the other factors.

Here are some questions from a measure of equity sensitivity

- It is really satisfying to me when I can get something for nothing at work.

- It is the smart employee who gets as much as he / she can while giving as little as possible in return.

- Employees who are more concerned about what they can get from their employer, rather than what they can give to their employer, are the wise ones.

- When I have completed my task for the day, I help out other employees who have yet to complete their tasks.

- Even if I received low wages and poor benefits from my employer, I would still try to do my best at my job.

- At work, my greatest concern is whether or not I am doing the best job I can.

Belief in a Just World

It is apparent that all people have a need to believe that they live in a world where people generally get what they deserve; there is justice in the end. Good deeds are rewarded; bad are punished. This belief enables them to confront the world as though it were stable and orderly. Without these beliefs, it is difficult for people to commit themselves to the pursuit of long-range goals. The BJW has an adaptive function, which is why people are very reluctant to give up this belief. It is very distressing to be confronted with evidence that the world is not really just or orderly after all.

Here are some statements from a classic measure of the just-world beliefs:

- Basically, the world is a just place (J)

- People who get “lucky breaks” have usually earned their good fortune (J)

- Careful drivers are just as likely to get hurt in traffic accidents as careless ones (UJ)

- Students almost always deserve the grades / marks they receive in school (J)

- People who keep in shape have little chance of suffering a heart attack (J)

- The political candidate who sticks up for his principles rarely gets elected (UJ)

- In professional sport, many fouls and infractions never get called by the

referee (UJ) - By and large, people deserve what they get (J)

- Good deeds often go unnoticed and unrewarded (UJ)

- Although evil people may hold political power for a while, in the general course of history, good wins out (J)

- In almost any business or profession, people who do their jobs well rise to the top (J)

- People who meet with misfortune have often brought it on themselves (J)

Believing that the world is just seems to provide psychological buffers against the harsh realities of the world, as well as personal control over one’s own destiny. It is a way of eliminating injustice by victim derogation; that is why people blame victims of a range of misfortunes for their plight. People feel less personally vulnerable and have lower perception of risk because they believe they have done nothing to deserve negative outcomes. It seems the BJW developmental and life-span literature suggests that it is fairly stable across the life-span.

It is apparent that all people have a need to believe that they live in a world where people generally get what they deserve.

It possible for some people to believe that the world was just (people got what they deserve), unjust (the good and virtuous were punished) and the a-just or random world where just deeds were randomly rewarded and punished. Also, there are different worlds: the personal, interpersonal, and social world. People can believe in different worlds for different reasons. One might believe the political and economic world to be unjust, but the world of personal relations just. But most of all, for many the world was a-just. It rains on the just and unjust alike (Matthew 5). However, some would argue that whether or not the world is just, it could be made fairer.

It may be more seriously disadvantageous to believe that the world is unjust as opposed to just. Imagine believing that good actions are punished, as opposed to rewarded, or that good people are assassinated while dictators live to an old age. A major development at the turn of the millennium was to view the BJW as a healthy coping mechanism, rather than being the manifestation of antisocial beliefs and prejudice. Studies have portrayed BJW beliefs as a personal resource or coping strategy, which buffers against stress and enhances achievement behaviour. Of course, as pointed out above, one could believe in a just personal world, an a-just interpersonal world, and an unjust political world at the same time. Further, there must be degrees to which the world is just or unjust, not simply a stark binary option.

For the first time, BJW beliefs were seen as an indicator of mental health and planning. This does not contradict the more extensive literature on BJW and victim derogation. Rather it helps explain why people are so eager to maintain their beliefs, which may be their major coping strategy. BJW is clearly functional for the individual. Rather than despise people for believing that the world is (relatively) just, which certainly we teach our children, the BJW may be seen as a fundamental, cognitive coping strategy. However, the directionality is not always clear: Do mentally healthy people believe that the world is just, or do just-world believers deal better with the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune”? Or, indeed, is there actually a reciprocal causal relationship? Believing the world is just when it is not may be a maladaptive, bruising experience.

One question is how BJW is related to other coping strategies which are favoured by healthy individuals who have low BJW beliefs. Again, the focus is on how BJW relate to personal experiences, rather than those of others. Is it true that “what goes around comes around”? For the most part, good deeds are rewarded, and vice versa. That the bad are punished and the good rewarded is what we teach our children, though we no doubt all believe that this simple observation needs to carry a caveat and be explained.

Conclusion

Now, more than ever, people seem sensitive to issues of fairness at work – who is promoted, selected, and sacked, and why. Why people are paid what they are. How bullies are dealt with. The psychological research has shown that we can understand how, when, and why people take different positions with respect to what they think is just and fair, which helps explain how they act as they do. And beware the manager who is not able to understand and deal with these issues.