By Javier Cabello Llano, Professor Ambika Zutshi and Sahan J. Fernando

The jewelry industry is facing rising pressure to ditch wasteful, exploitative practices and embrace sustainability. Here, the authors present their a vision of how the 10R framework could be applied to give the sector a much-needed revamp incorporating the principles of the circular economy.

The jewelry industry

The global jewelry industry, valued at 300 billion dollars and with an estimated growth rate of 4 percent annually until 2030, is heavily dependent on non-renewable resources. The rising demand for jewelry has raised concerns over the environmental and social impacts of the industry beyond the on-material sourcing, to incorporate carbon emissions and labor exploitation. Increasing pressures to adopt sustainable practices (Lin & Sai, 2023) and the principles of sustainable fashion emphasize the importance of reducing the environmental and social impacts of the jewelry industry by facilitating circularity in business models.

The adoption of circularity in the jewelry industry offers three benefits. First, it enhances economic value through securing raw material supply, reducing cost, innovation, and minimizing waste (Faccioli et al., 2023). Second, enhanced economic value enables organizations to shift capital and resources to areas of high productivity and greater yield, such as product availability, new product development, and business expansion. Third, circularity in the jewelry industry appeals to a sustainability-conscious customer base in the target market and enhances brand equity (Lin & Sai, 2023). Here, we present our recommendations for supply chain practitioners using the 10R framework to facilitate the circular economy in the jewelry industry.

The 10R framework for the jewelry industry

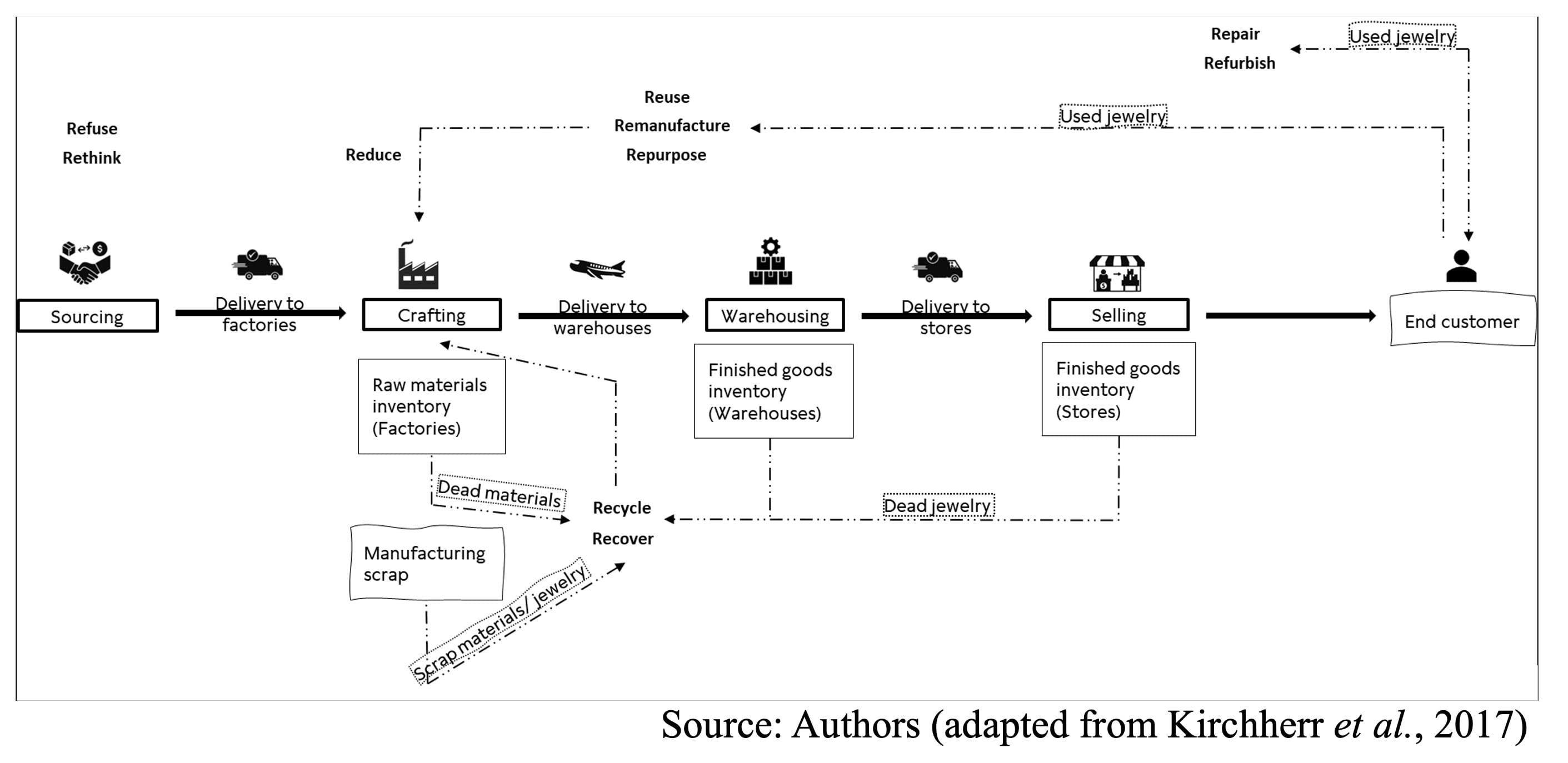

Figure 1 illustrates operationalization across the various stages of the jewelry supply chain to facilitate circularity by optimizing material usage and extending product life cycles. The jewelry life cycle can be broadly classified into three categories of circularity.

Figure 1: The 10R framework in the jewelry industry

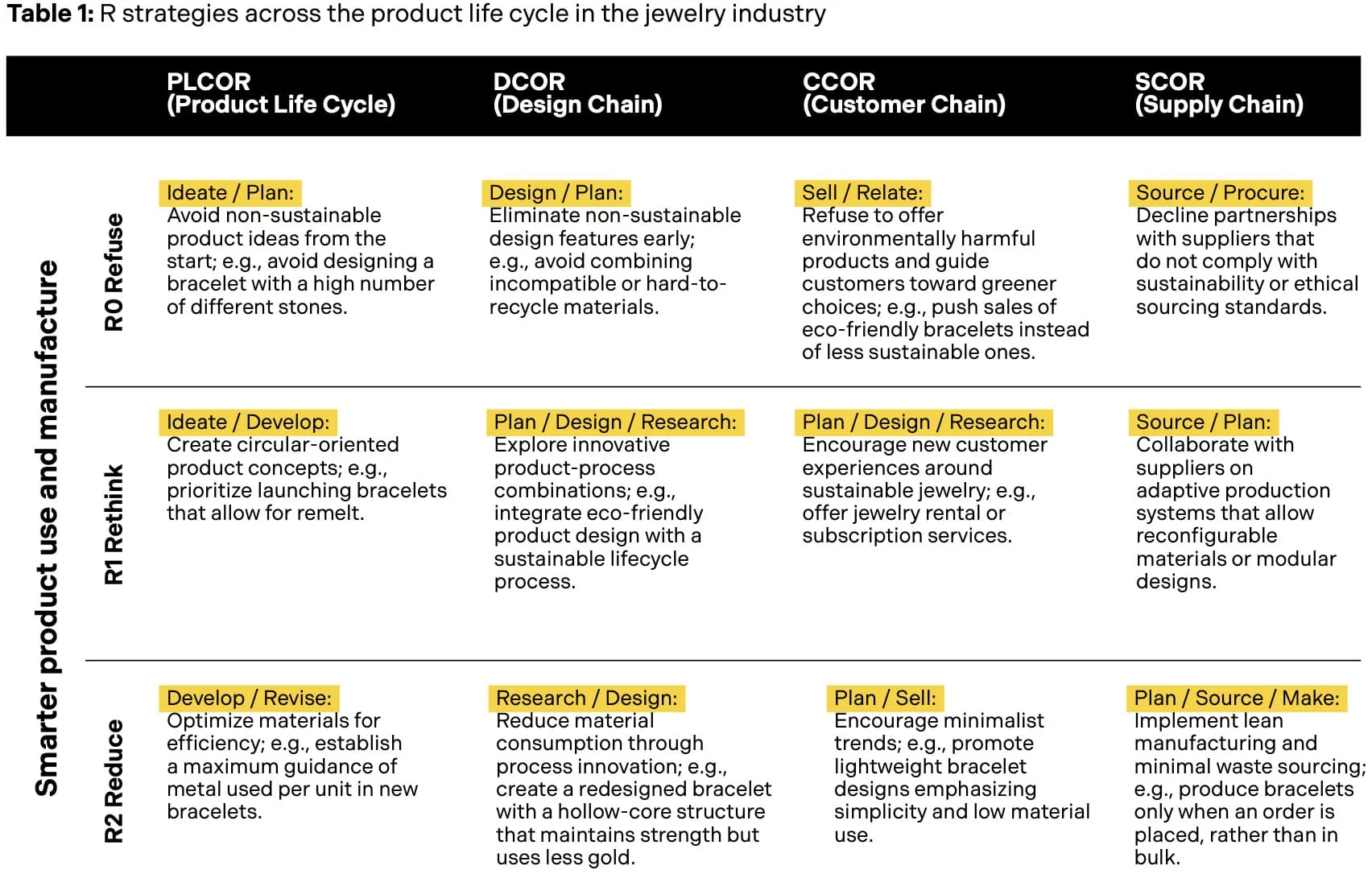

Category 1: Smarter product use and manufacture

This first category includes thought-provoking steps for practitioners to advance the circular economy in the jewelry industry by refusing (R0 Refuse) unsustainable materials and rethinking (R1 Rethink) design and production to minimize waste and resource use (R2 Reduce). By adopting alternative, eco-friendly materials and more ethical practices, manufacturers can reduce reliance on non-renewables and lower environmental impact.

Category 2: Extend the lifespan of the product and its parts

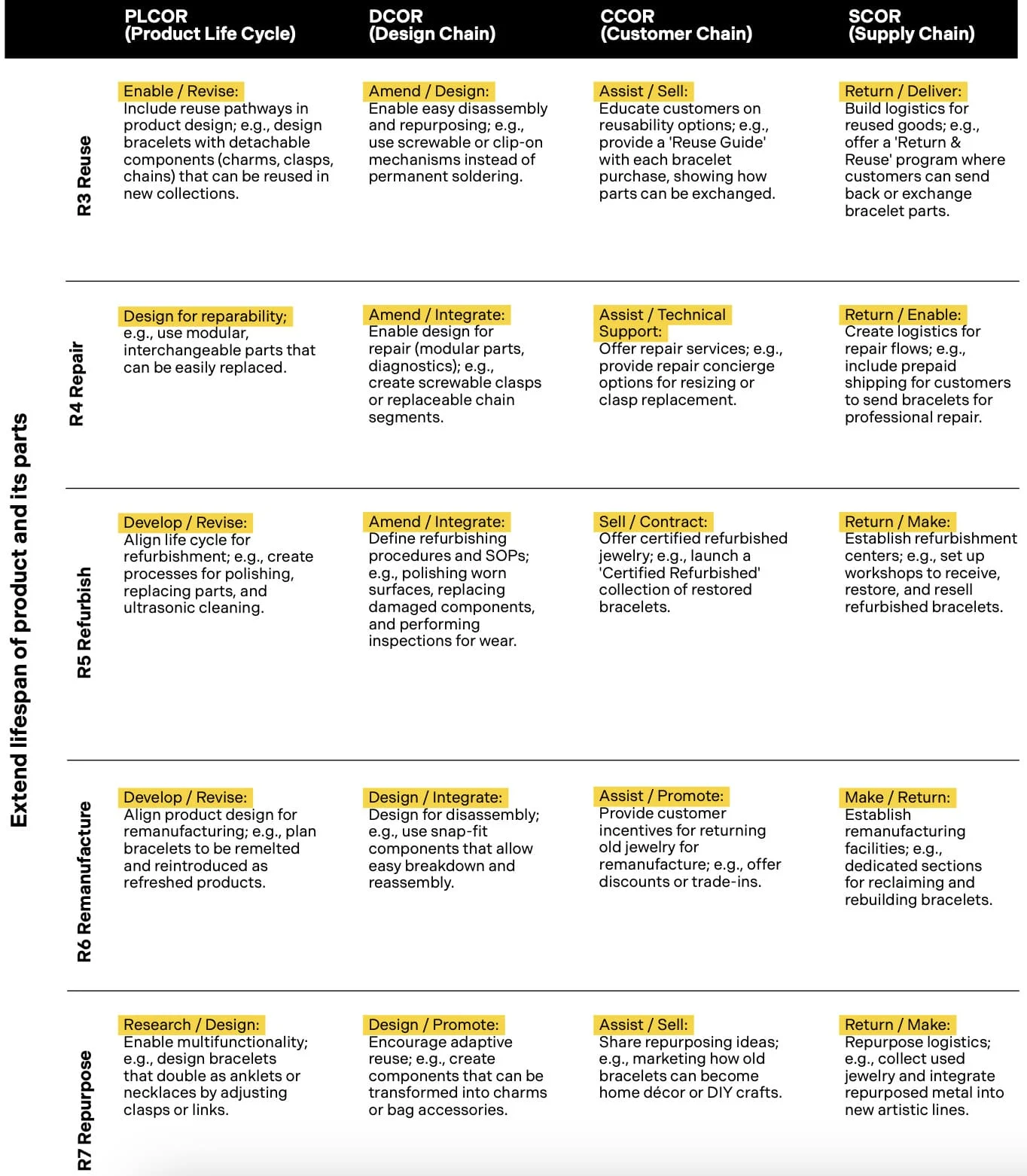

This second category is about extending product lifespans using multiple options, including reusing (R3 Reusing), repairing (R4 Repair), and refurbishing (R5 Refurbish) of jewelry pieces. Nonetheless, staying competitive requires a constant supply of new designs and poses a challenge for circular opportunities when trying to remanufacture (R6) and repurpose (R7) existing jewelry items into new designs.

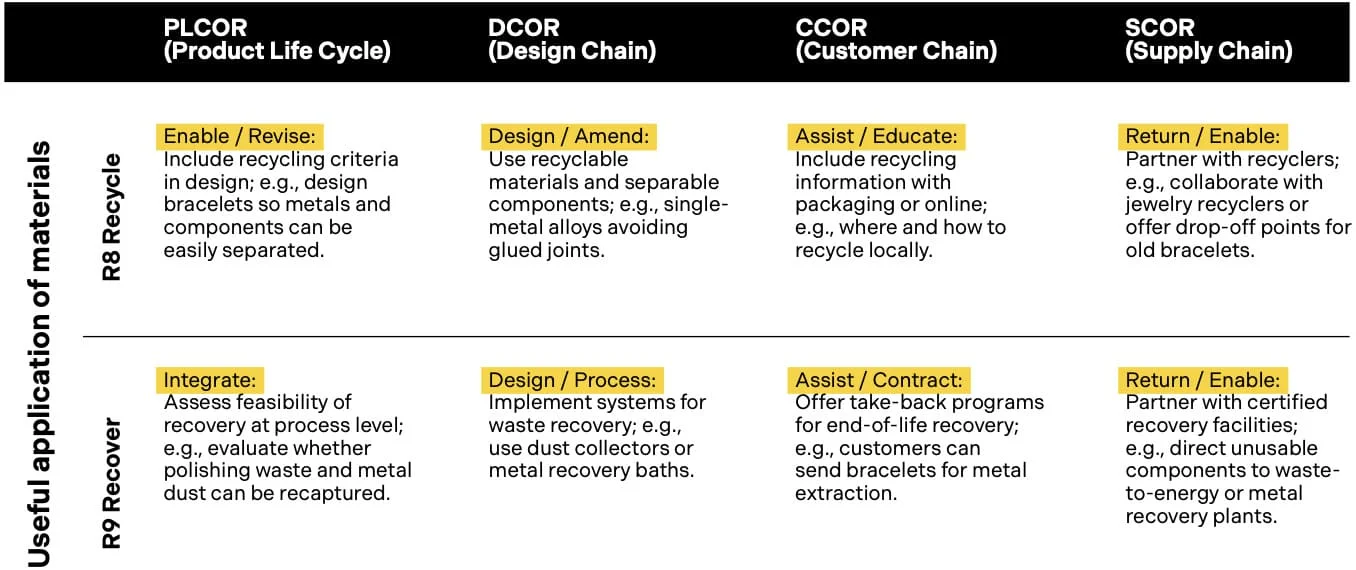

Category 3: Useful application of materials

This category includes the critical step in closing the loop by establishing recycling systems (R8 Recycle) and recovering (R9 Recover) materials from unsold or discarded jewelry, supporting both sustainability and emerging consumer preferences. This is achievable, as demonstrated by some start-ups (e.g., Oushaba, Lylie, The Royal Mint’s 886, So-Le Studio) who have been focusing on creating jewelry from discarded materials.

There are several opportunities for practitioners to move the conversation from circulatory challenges in the jewelry industry to having practical strategies to achieve the same. Table 1 overviews these strategies by showcasing the example of a bracelet. It outlines actionable interventions across the Level 1 processes for APICS frameworks: Product Life Cycle (PLCOR), Design Chain (DCOR), Customer Chain (CCOR), and Supply Chain (SCOR). These strategies can assist managers and industry partners to design and manage products with circularity in mind, whilst simultaneously balancing their profit margins. From selecting sustainable raw materials and modular designs to enabling take-back programs and recycling pathways, these strategies encourage reflection on critical questions such as, “Have you considered alternate materials or adaptive product designs?” or, “How can your supply chain better support product recovery and reuse?” These recommendations aim to support more sustainable and resilient business models within the jewelry sector.

In summary, the first step in working towards circularity in the jewelry industry is identification, followed by integrated efforts from key stakeholders across the upstream and downstream supply chain. This piece provides reflection and action points for supply chain practitioners using the 10R framework, incorporating aspects of reverse logistics systems for product return, use of standardized and recyclable materials, and design simplification to facilitate disassembly and reuse. Further, embracing extended producer responsibility (EPR) and cross-sector partnerships can unlock broader circular solutions, particularly in the use of non-renewable resources. Nonetheless, establishing a circular economy in the jewelry industry is only a beginning. It must be continuously evaluated and improved in the design, sourcing, production and disposal stages to remain effective and resilient over time.

About the Authors

Javier Cabello Llano is a PhD student at the Technical University of Denmark. His research focuses on supply chain and operations management, with a big interest in how companies can remain responsive while pursuing sustainability. He is especially engaged with challenges in the fashion industry and other dynamic markets, aiming to bridge performance and responsibility.

Professor Ambika Zutshi is Dean of ACU’s Peter Faber Business School and author of over 100 publications focused on CSR, higher education, supply chain management, and stakeholder relationships. Editorial board member of the International Journal of Consumer Studies, and editorial advisory board member of Management of Environmental Quality.