This article continues from Part I (in the last issue of The European Business Review) and provides insights into two critical domains of the 50+20 vision: a) the perspectives of stakeholders of management education (students, alumni, civil society, the business community, NGOs, and management scholars and administrators), and b) the collaboratory as the essence of the 50+20 vision.

In collaboration with the youth organisation Challenge: Future1, we asked 1091 students from the age of 18 to 32 years from 79 countries: “Which group of people is most responsible for not acting on time, even though humanity is approaching an ecological catastrophe?” On a scale from 1 (not responsible) to 6 (responsible) the students were asked to rate the different groups.

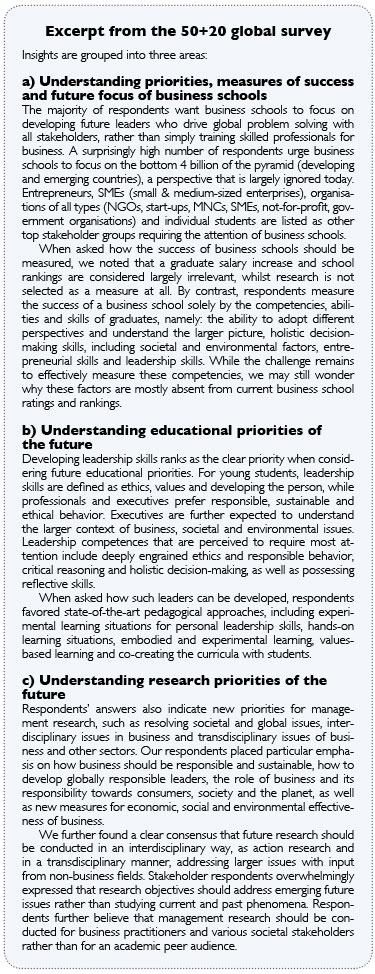

Today’s youth considers “us as human beings” and “political leaders” as by far the most responsible (51 percent and 43 percent respectively), followed by “international organisations” (31 percent), “business” and “the educational system in general” are considered somewhat responsible (24 and 22 percent). It was noteworthy to find to what degree our current youth considers itself co-responsible (“we as human beings”), while they attribute only a small responsibility to “business schools” and “the financial markets” (15 percent and 16 percent respectively).

To understand what other members of the community have to say about the future of management education, we conducted a global survey and collected 145 responses from 37 countries.The responses gathered from our community suggest a fundamental shift in priorities and a swiftly growing awareness of the broader issues that affect us globally. In our visioning work we incorporated these responses into the larger societal context and derived a vision that suggests three revised roles for management education. We embrace the example set by the youth and suggest that management education should assume a sense of co-responsibility in shaping tomorrow’s world. Management education is very well positioned to play a vital role in addressing the concerns outlined above.

The collaboratory – the essence of the vision

The philosophy of the collaboratory involves a circular space that is open to concerned stakeholders for any given issue. Action learning and research join forces in collaboratory – where students, educators and researchers work with members of all facets of society to address current dilemmas. The collaboratory is a key feature of the 50+20 vision, a new philosophy in promoting management education for the world – as seen in the context of the three roles and corresponding enablers discussed previously.

The collaboratory represents an open-source metaspace: a facilitated platform based on open space and consciousness building technologies. Once understood, a collaboratory can be established anywhere, virtual or real, within companies, communities – or within a management school. Its primary strengths lie in enabling issue-centered learning, conducting research for a sustainable world, and providing open access between academia and practice. The collaboratory also offers a powerful alternative for public debate and problem solving, inclusive of views from business and management faculty, citizens, politicians, entrepreneurs, people from various cultures and religions, the young and the old. Everybody must have a voice, hence the need for a transdisciplinary approach.

A collaboratory is conducted without formal separation between knowledge production and knowledge transfer, while focusing on visceral real-life issues and providing solutions that are driven by issues, not theory. Participants in a collaboratory employ problem-solving tools and processes that are iterative and emergent. Proposed solutions are directly tested, contested and modified while supporting both knowledge production and diffusion, which occur in parallel.

The co-creation of meaning

Of course, the idea of open and equal collaboration is nothing new. Sometimes it works, sometimes not. One may easily mistake the philosophy of the collaboratory as a free-for-all gathering of affable individuals who automatically become friends and miraculously agree on credible resolutions without encountering any significant obstacles. We know all too well that without the proper systemic approach a gathering of this kind may disintegrate following (for example) a prolonged argument over the minutiae of an issue under discussion. Skilled facilitation and a robust methodology are therefore required to address the complexities of vested interests, group dynamics, and problem resolution. To us, the collaboratory is a living experiment whereby we co-create its meaning, its power and strength, during each session held around the world.

Paradigm-shifting innovations do not usually occur in well-established institutions, but tend to emerge amongst the outliers: the smaller, hidden and often ignored pockets of creativity that are also part of the colourful landscape of management education. We refer to these innovative initiatives as emerging benchmarks: an initial set of examples related to the three proposed roles of responsible leadership. Collecting emerging benchmarks runs parallel to the 50+20 vision development, and will continue as the initiative grows.

The evolution of the collaboratory concept

The term collaboratory was first introduced in the late 1980s2 to address problems of geographic separation in large research projects related to travel time and cost, difficulties in keeping contact with other scientists, control of experimental apparatus, distribution of information, and the large number of participants. In their first decade of use, collaboratories were seen as complex and expensive information and communication technology (ICT) solutions supporting 15 to 200 users per project, with budgets ranging from 0.5 to 10 million USD.3 At that time, collaboratories were designed from an ICT perspective to serve the interests of the scientific community with tool-oriented computing requirements, creating an environment that enabled systems design and participation in collaborative science and experiments.

The introduction of a user-centered approach provided a first evolutionary step in the design philosophy of the collaboratory, allowing rapid prototyping and development circles. Over the past decade the concept of the collaboratory expanded beyond that of an elaborate ICT solution, evolving into a “new networked organisational form that also includes social processes, collaboration techniques, formal and informal communication, and agreement on norms, principles, values, and rules”.4 The collaboratory shifted from being a tool-centric to a data-centric approach, enabling data sharing beyond a common repository for storing and retrieving shared data sets.5 These developments have led to the evolution of the collaboratory towards a globally distributed knowledge network that produces intangible goods and services capable of being both developed and distributed around the world using traditional ICT networks.

Initially, the collaboratory was used in scientific research projects with variable degrees of success. In recent years, collaboratory models have been applied to areas beyond scientific research and the national context. The wide acceptance of collaborative technologies in many parts of the world opens promising opportunities for international cooperation in critical areas where societal stakeholders are unable to work out solutions in isolation, providing a platform for large multidisciplinary teams to work on complex global challenges.

The emergence of open-source technology transformed the collaboratory into its next evolution. The term open-source was adopted by a group of people in the free software movement in Palo Alto in 1998 in reaction to the source code release of the Netscape Navigator browser. Beyond providing a pragmatic methodology for free distribution and access to an end product’s design and implementation details, open-source represents a paradigm shift in the philosophy of collaboration. The collaboratory has proven to be a viable solution for the creation of a virtual organisation. Increasingly, however, there is a need to expand this virtual space into the real world. We propose another paradigm shift, moving the collaboratory beyond its existing ICT framework to a methodology of collaboration beyond the tool– and data-centric approaches, and towards an issue-centered approach that is transdisciplinary in nature.

Holding a space

Translating the concept of the collaboratory from the virtual space into a real environment demands a number of significant adjustments, leading us to yet another evolution. While the virtual collaboratory could count on ICT solutions to create and maintain an environment of collaboration, real-life interactions require facilitation experts to create and hold a space for members of the community, jointly developing transdisciplinary solutions around issues of concern. The ability to hold a space is central to the vision of management education.

The technology involved with holding a space implies the ability to create and maintain a powerful and safe learning platform. Such a space invites the whole person (mind, heart, soul and hands) into a place where the potential of a situation is fully realised. Holding a space is deeply grounded in our human heritage, and is still considered an important duty of the elders amongst many indigenous peoples. In Western society, good coaches fulfill a similar role, including the ability to be present in the moment, listening with all senses, being attuned to the invisible potential about to be expressed. As a result, what needs to happen, will happen. Facilitation and coaching experts understand the specific challenges involved in setting up an environment in which a great number of people can meet to discuss solutions that none of them could develop individually. Coaching and facilitation solutions already exist to create and hold such spaces, but are nevertheless distinctly different in a felt sense from the ICT-driven virtual collaboratories we have seen over the past two decades.

The evolution from the virtual collaboratory bears its own challenges and opportunities. In the co-creative process of the 50+20 vision, we learned to appreciate the power of the collaboratory both in real-life retreats as well as interactions between our gatherings. We propose that the next evolutionary step of the collaboratory will include both the broader community of researchers engaged in collaboratories around the world, as well as stakeholders in management education who seek to transform themselves by providing responsible leadership.

In our new definition, a collaboratory is an inclusive learning environment where action learning and action research meet. It involves the active collaboration of a diversified group of participants that bring in different perspectives on a given issue or topic. In such a space, learning and research is organised around issues rather than disciplines or theory. Such issues include: hunger, energy, water, climate change, migration, democracy, capitalism, terrorism, disease, the financial crisis, transformation of economic systems and educational reform amongst other similarly pressing matters. These issues are usually complex, messy and challenging to resolve, demanding creative, systemic and divergent approaches. The collaboratory’s primary aim is to foster collective creativity.

The collaboratory is a place where people can think, work, learn together, and invent their respective futures. Its facilitators are highly experienced coaches who act as lead learners and guardians of the collaboratory space. They see themselves as transient gatekeepers of a world in need of new solutions. Subject experts are responsible for providing relevant knowledge and contributing it to the discussion in a relevant and pertinent matter. Students will continue to acquire subject knowledge outside the collaboratories – both through traditional and developing channels (such as online or blended learning).

As such, the faculty is challenged to develop their capacities as facilitators and coaches in order to effectively guide these collaborative learning and research processes. To do this, they must step back from their role as experts and rather serve as facilitators in an open, participative and creative process. Faculty training and development needs to include not only a broad understanding of global issues, but also the development of facilitation and coaching skills.

The circular space of the collaboratory can become the preferred meeting place for citizens to jointly question, discuss and construct new ideas and approaches to resolve environmental, societal and economic challenges on both a regional and global level. Collaboratories should always reflect a rich combination of stakeholders: coaches, business and management faculty, citizens, politicians, entrepreneurs, people from different regions and cultures, youth and elders. Together they assemble differences in perspective, expertise and personal backgrounds, thereby adding a vital creative edge to every encounter, negotiation or problem-solving session.

We envision that the collaboratory of the future will contain a number of attributes and approaches. Most importantly, the collaboratory will be centred on real-life challenges, providing solutions that are problem driven, not theory driven. Problem definitions will be systematically created and assessed by professors, experts, students, researchers and practitioners, taking into account environmental dynamics, social dynamics, political dynamics, anthropology and systems dynamics. Addressing complex global problems requires a transdisciplinary and systemic approach, employing individuals with variable perspectives in order to understand and resolve an issue. Members of a collaboratory will employ problem-solving processes that are iterative and emergent, without formal separation between the production and transfer of knowledge. Finally, proposed solutions must be directly tested, contested and modified while supporting both knowledge production and diffusion, which occur parallel to one another.

As such, a collaboratory becomes a powerful tool to hold a space for future-relevant learning and research. Research will support the resolution of global issues by embracing action research as a standard approach, as well as employing various future-oriented methodologies. Subject experts, including professors from various disciplines serve as knowledge curators, selecting which types of information and input are appropriate to help uncover new solutions. Educators meanwhile ensure that students are able to integrate the experience in the collaboratory through effective facilitation and coaching methodologies, including self-reflection, creativity, systemic and critical thinking. As a result, a collaboratory is a place where action learning and action research join forces, where students and researchers work with all facets of society that are related to the issue under examination. The collaboratory is the key feature of our vision, a distinguishing factor in promoting management education for the world.

Extracts from chapter 5 of the book “Management education for the world: A vision for business schools serving people and planet”, published by Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, U.K. in June 2013. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher.

Management Education for the World speaks to everybody concerned or passionate about the future of management education. It presents a vision for the transformation of management education in service of the common good. And it explains how such a vision can be implemented in practice. For more information please visit: www.50plus20.org/book

About the Authors

Katrin Muff (DBA) is Dean of Business School Lausanne (BSL), Switzerland, since 2008 (www.bsl-lausanne.ch). Under her leadership, the school expanded its vision from a focus on entrepreneurship to embrace also responsibility and sustainability into a three-pillar vision for both education and applied research. She previously worked for Schindler in Switzerland and Australia and for Alcoa in Switzerland and the United States, and as General Manager of their first Russian manufacturing plant in Moscow, Russia. She is the co-founder of Yupango, a coaching consultancy dedicated to developing start-up companies and training management teams. She can be contacted at: [email protected]

Thomas Dyllick (Dr. oec. HSG) is a Professor of Sustainability Management and Managing Director of the Institute for Economy and the Environment at University of St. Gallen, Switzerland. He currently serves as University Delegate for Responsibility and Sustainability. He was vice-president in charge of teaching and quality development (2003–2011) and dean of the University of St. Gallen’s Management Department (2001-2003). He is the author of several books and many publications in the fields of corporate sustainability, sustainable development, and management education, and serves on a number of boards. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

Mark Drewell MA (OXON), FRSA is the CEO of the Globally Responsible Leadership Initiative, a worldwide partnership of companies and business schools taking action to develop the next generation of globally responsible leaders. He spent 20 years working in South Africa with Barloworld Limited where he headed Corporate Affairs, Investor Relations and Group Marketing and led the company’s move into sustainability. His contributions to society include having chaired the boards of The World’s Children’s Prize for the Rights of the Child and the Endangered Wildlife Trust. He is a frequent public speaker. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

John North is a next generation integrational entrepreneur. He worked as an international strategy consultant advising Fortune 500 companies and was the founding head of Accenture’s sustainability practice in Ireland. He came back to South Africa in 2009, where he combines local work as the senior advisor to the Albert Luthuli Centre for Responsible Leadership, University of Pretoria and the Project Head of UN-backed Globally Responsible Leadership Initiative. In the latter role he is focussed on a series of implementation projects of the 50+20 Agenda of management education in service of society (50plus20.org). He can be contacted at: [email protected]

Paul Shrivastava (PhD) is the David O’Brien Distinguished Professor of Sustainable Enterprise at the John Molson School of Business, Concordia University, Montreal. He also serves as Senior Advisor on sustainability at Bucknell University and the Indian Institute of Management-Shillong, India. In addition, he serves on the Board of Trustees of DeSales University, Allentown, Pennsylvania. He also leads the International Research Chair in Art and Sustainable Enterprise at ICN Business School, Nancy, France. In these roles he combines scientific and artistic approaches to sustainable development. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

Jonas Haertle is Head of the Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME) secretariat of the United Nations Global Compact Office. Previously, he was the coordinator of the UN Global Compact’s Local Networks in Latin America, Africa and the Middle East. Prior to joining the United Nations, Jonas worked as a research analyst for the German public broadcasting service Norddeutscher Rundfunk. He can be contacted at: [email protected]

References

1. Challenge: Future is a global youth organisation, see www.challengefuture.org

2. Wulf, W. (1993): The collaboratory opportunity. Science, 261, 854-855

3. Sonnenwald, D.H., Whitton, M.C., &Maglaughlin, K.L. (2003). Scientific collaboratories: evaluating their potential, Interactions, 10(4), 9–10, New York: ACM Press.

4. Cogburn, 2003, p. 86

5. Chin, G., Jr., & Lansing, C. S. (2004). Capturing and supporting contexts for scientific data sharing via the biological sciences collaboratory, Proceedings of the 2004 ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work, 409-418, New York: ACM Press.

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-218x150.jpg)

![“Does Everyone Hear Me OK?”: How to Lead Virtual Teams Effectively iStock-1438575049 (1) [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/iStock-1438575049-1-Converted-100x70.jpg)