By Daniel Trabucchi & Tommaso Buganza

The platform revolution has already taken place, but we link the idea of platforms with Big Tech like Amazon or Meta and digital-native start-ups like Airbnb and Uber. In this article, we explore the concept of Platform Thinking, perceiving platforms as a tool to foster digital business transformation for established firms like Telepass, John Deere, and Klöckner.

Over the last two decades, the business landscape has changed radically. We can prove it easily with two lists:

2003: Microsoft, General Electric, ExxonMobil, Walmart, Pfizer, Citigroup, Johnson & Johnson, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, IBM

2023: Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Meta, Tesla, Berkshire Hathaway, Eli Lily, TSMC

These are the 10 companies with the highest market capitalisation in 2003 and 20231. We can get three main insights by comparing the lists: only one company remained in the Top 10 two decades later (Microsoft), and the industries had shifted quite clearly from product and energy companies to tech companies. Finally, of course, five out of the 10 companies in 2023 are “platform companies”.

The Big Tech MAGMA (Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet-Google, Meta, and Amazon) established their leadership by applying platform models and became, along with “younger giants” like Airbnb and Uber, flagship cases of the platform revolution. But what are platforms? Can we really compare these companies under the same label? And, more interestingly, is it all a matter of digital native companies? How can established – non-digital-native – companies exploit platform thinking and leverage the learning from (younger) digital companies?

What is a platform?

The question “what is a platform?” is not an easy one to answer. We recently wrote a book, Platform Thinking, which dedicates entire chapters to the peculiarities of the various typologies of platforms. Let’s start by defining what a platform is not. Not every value-creation mechanism based on a linear value chain is a platform. Porter described the linear value chain as a sequence of primary activities to transform raw materials from suppliers into finished products for the market, plus all the other activities needed to support these primary ones (e.g., training or hiring). This model easily applies to product or service companies such as General Electric, Johnson & Johnson, FedEx, and many others.

However, if we look at the aforementioned MAGMA cases, this definition doesn’t seem able to fully describe their value-creation mechanisms. We need to introduce the concept of platform (and, more precisely, different typologies of platforms) to describe their value-creation mechanisms.

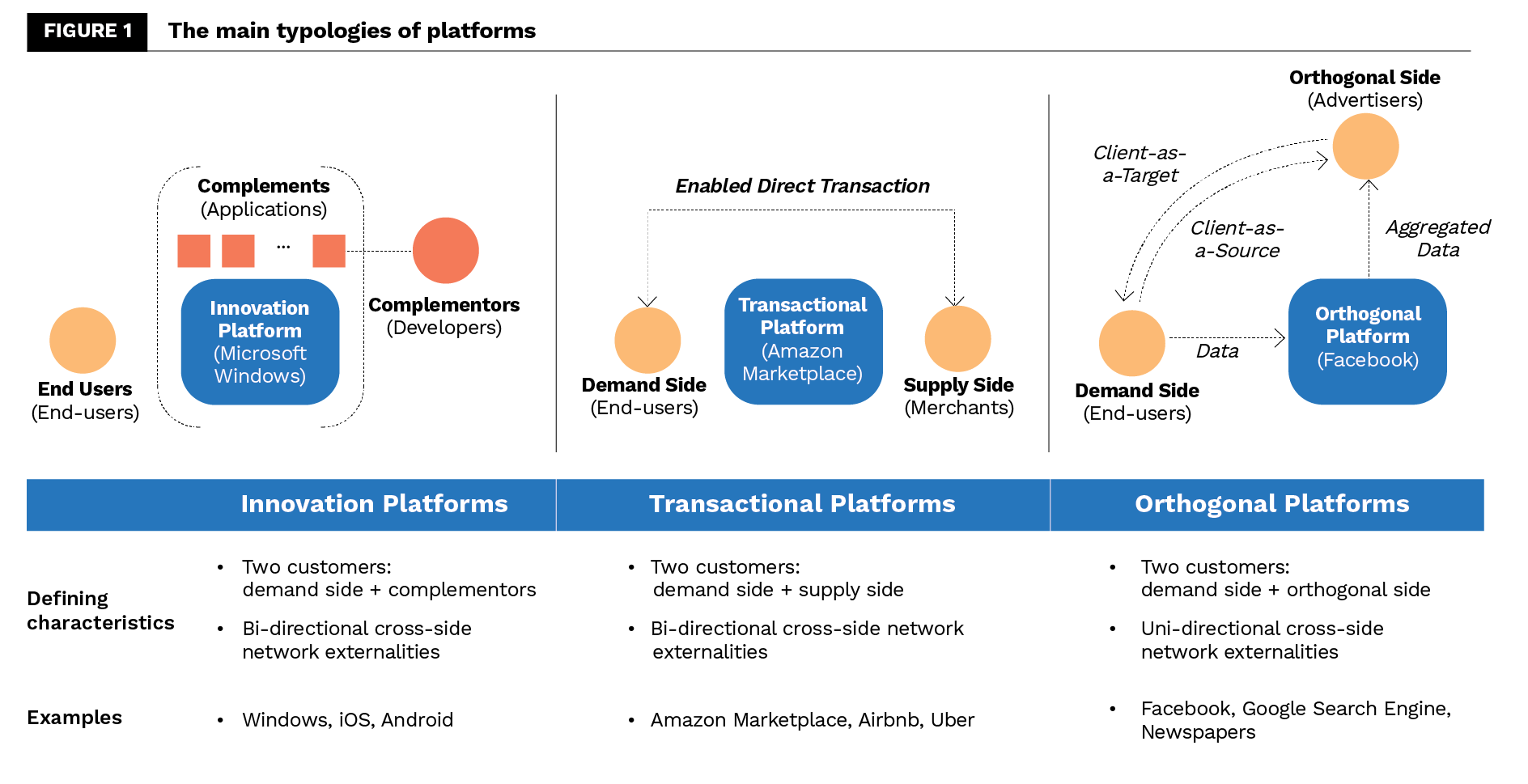

Microsoft (and, more precisely, the Windows operating system) is the typical case of an innovation platform2 – and, indeed, one of the very first of these. Innovation platforms are technological systems open to two different customers: computer users on the one hand and “complementors” on the other. Complementors are organisations or individuals that can foster innovation on top of the platform, delivering their own products to the end users. In other words, Microsoft offers Windows to the final users but, at the same time, it offers its APIs and software development kits to software developers who wish to code on top of the operating system. In a nutshell, both the end users and the software developers (like Adobe or Autodesk) are customers in Microsoft’s eyes. Moreover, innovation platforms are subject to the so-called bidirectional cross-side network externalities3: the more users, the more value for software developers, and vice versa.

Amazon is a different and very varied case. It started off as a linear value chain company delivering books and, even now, still has important revenue sources managed as linear value chains, like AWS4,5. However, if we focus on the Amazon Marketplace, we can see a perfect case of a transactional platform6,7. We are clearly customers any time we log on to Amazon Marketplace to buy anything we need, from a book to a stabiliser, and we correctly perceive the merchant selling the stabiliser as a provider. From Amazon’s point of view, though, there are no customers and providers, but only customers and customers. People buying any product on Amazon are obviously customers, but companies selling those products are also Amazon’s customers. They receive the chance to reach one of the widest potential markets in the world, a delivery service, payment services, and much more. To underline their customer role, the sellers pay Amazon a fee for each product sold (if they were providers, they would be paid instead).

In this case, the platform is not the basis upon which to develop new and innovative products but rather an enabler of one-to-one transactions. There are two customers (buyers and sellers) and, again, bidirectional cross-side network externalities that make this platform so valuable; the more buyers, the more potential value perceived by the sellers, and vice versa.

Meta is the last platform typology we present. The reason we consider Facebook, as well as Instagram by Meta, a platform is mainly the presence of advertisers. Advertisers pay Facebook to reach as many viewers as possible and target them with incredible precision, thanks to the data generated by the users themselves. This makes Facebook an orthogonal platform8,9. As in the previous cases, there are two customers (the end users and the advertisers) but, here, there is not a one-to-one transaction. On the contrary, the second side, the advertisers, see the first side as both a target for commercial purposes (but the transaction will happen somewhere else) and as a source of valuable information to target them more accurately. There are still externalities, but only unidirectional; the more end users, the more value for advertisers. The other way around (more advertisers, more value for end users) is just not verified.

These three non-linear value-creation mechanisms are very different, but they share two key features that allow us to define the concept of the platform: 1) the presence of two (or more) groups of interdependent customers and 2) the presence of cross-side network externalities that drive the growth and potential scale of platforms.

(Non-digital-native) established firms fostering innovation through Platform Thinking

So far, all the examples we have provided are Big Tech and / or digital-native start-ups mainly headquartered in Silicon Valley.

However, it would be a big mistake to think that these are the only companies that can benefit from platform-based value-creation mechanisms.

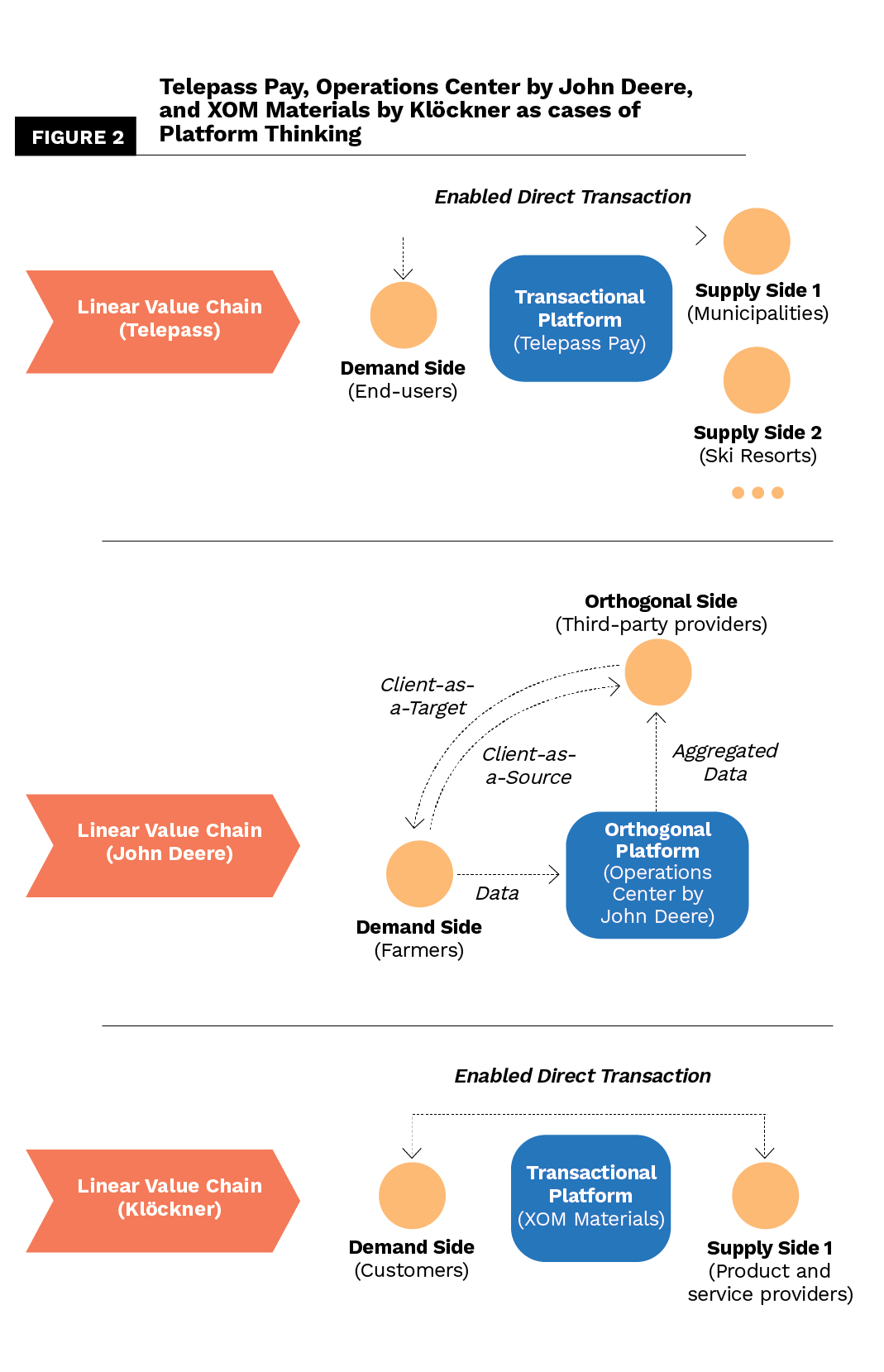

With the concept of “Platform Thinking“, we refer to the ability to foster innovation by seeing possible platform mechanisms everywhere. It might seem strange but, once unlocked, the platform way of thinking can foster innovation even in established, industrial, non-digital companies, as in the cases of Telepass (Italy), John Deere (USA), and Klöckner (Germany).

Telepass and Telepass Pay

From 1989, Telepass, once incorporated into Autostrade per l’Italia, the Italian motorway company, revolutionised the driving experience with its automated toll collection system.

The system enabled motorists to glide through toll stations, offering a seamless journey without the “stop and go” of traditional toll booths. Telepass is an example of how platforms can revolutionise the entire company’s value-creation mechanism10.

Initially, the Telepass service was a typical linear value chain, directly linking the company to the customer through a unique service offering.

This all changed in 2017, when Telepass expanded its horizons with the launch of Telepass Pay, a multiple-service smartphone app based on a transactional platform mechanism. Now, drivers could pay not only for tolls but also for parking, fuel, and even car services like washing or maintenance through a unified system. The introduction of Telepass Pay brought in additional customer groups – parking facilities, fuel stations, and service providers – and transformed Telepass into a platform enabling service transactions between them and drivers.

This strategic move turned Telepass into a multi-sided transactional platform leveraging cross-side network externalities; the more drivers, the bigger the value for service providers, and vice versa.

A start-up wanting to introduce a similar platform would encounter the so-called “chicken and egg” paradox: drivers are attracted by service providers who are attracted by drivers, but none of these sides are on board at the beginning. On the contrary, when launching Telepass Pay, Telepass already had 8 million users from the linear value chain service (toll payment) and had no paradox to face.

John Deere and the Operations Center

John Deere, founded in 1837, is well known for producing heavy-duty agricultural machinery. It’s an example of how incorporating Platform Thinking can extend the value-creation capabilities of a traditionally product-centric company relying on data11.

Initially, John Deere made its machinery “smart” by integrating sensors, GPS, and AI. Farmers used these sophisticated tools to collect detailed data, enhancing their agricultural productivity through “MyJohnDeere“. This smart equipment represented an advanced linear value chain, optimising activities like seeding and fertilisation through real-time data.

The transformative moment came when John Deere began seeing farmers not just as equipment users but as data providers. In 2013, Deere opened up MyJohnDeere through its “Operations Center“, a platform providing aggregated and anonymised farmers’ data to a number of third-party providers. This shift added a two-sided model with network externalities to the traditional linear value chain of the company (the production of heavy-duty agricultural machinery).

Previously, farmers used John Deere’s system to optimise seed planting. Transitioning to a platform model, John Deere managed to enable entities like Bayer to access a wealth of anonymised agricultural data. Bayer might analyse this data to create advanced seeds or fertilisers tailored to the identified conditions, establishing a feedback loop where farmers, utilising these products, enhance the platform’s collective intelligence.

This strategic move transformed John Deere into an orthogonal platform, allowing third parties to innovate using the aggregated data. It not only amplified the farmers’ capabilities but also catalysed a network effect, broadening the platform’s scope and attracting new participants to this knowledge-rich ecosystem.

Besides the obvious challenges of changing corporate culture, John Deere was able to leverage its brand, know-how with regard to agricultural equipment, and presence in approximately one-third of American arable acres. A start-up could hardly match these assets.

Klöckner and XOM Materials

Klöckner is an independent German producer-distributor of steel and metals. It operates between the big crude-steel suppliers, such as ThyssenKrupp and Tata Group, and the customers, such as construction companies, car makers, and phone and appliance manufacturers.

In the last decade, they have revolutionised a long-lasting and hard-to-change market with two moves.

In 2014, Klöckner launched Kloeckner Connect, a digital service allowing customers to make orders from any device, check on past orders, see what’s available in stock, look through the entire Klöckner catalogue, and place online custom orders. Although this represents a major innovation in the market, we can still consider it to be a (digital) linear value chain service.

The game-changer came with the launch of XOM Materials in early 2017. XOM is a transactional platform where Klöckner’s customers (later joined by many others) form the demand side, and the supply side is enriched not just by Klöckner’s products but also by offerings from various third-party vendors, competitors, and service providers12,13.

This strategic move turned them from a metal producer and distributor into one of the leading steel service centre companies worldwide.

XOM Materials leveraged Klöckner’s established assets, like their extensive customer network, to generate cross-side network externalities. As more customers and suppliers joined, the value and efficiency of the network grew for all, demonstrating the potential of established companies to pivot into a transactional platform model even more successfully than start-ups.

Takeaways for Platform Thinkers

These six stories let us define platforms (Microsoft Windows, Amazon Marketplace, and Facebook) and how platforms can help established firms foster digital business transformation (Telepass Pay, Operations Center, XOM Materials).

At this point, we can leave behind the usual preconception about platforms. They are not just for digital native start-ups or Big Techs. We can, indeed, define Platform Thinking as the ability to use platform-based mechanisms to unlock digital business transformations14, and unveil the three key insights of this article:

- “Platform” is a broken word. We need more labels – like “innovation“, “transactional“, and “orthogonal” – to capture the complexity of the value creation models around us.

- Platforms are for everyone. Established traditional companies based on a linear value chain can also leverage Platform Thinking to foster digital business transformation.

- Platform Thinking builds on established firms’ idle assets (like data, customers, brand, or existing relationships), opening avenues for value exploitation and innovation.

About the Authors

Daniel Trabucchi and Tommaso Buganza are, respectively, Senior Assistant Professor and Full Professor at the School of Management of Politecnico di Milano. They are featured in the Thinkers50 Radar list 2024. Their main area of research is Platform Thinking, which focuses on how platforms can be used to foster digital business transformation. They co-founded Symplatform https://symplatform.com/, the international symposium for academics and managers working on platforms, and Platform Thinking HUB, the observatory where the innovation leader community can explore innovation through platforms. They are the authors of Platform Thinking – READ the past. WRITE the future, published by Business Expert Press in 2023. You can find out more about their work on platformthinking.eu https://platformthinking.eu/.

Daniel Trabucchi and Tommaso Buganza are, respectively, Senior Assistant Professor and Full Professor at the School of Management of Politecnico di Milano. They are featured in the Thinkers50 Radar list 2024. Their main area of research is Platform Thinking, which focuses on how platforms can be used to foster digital business transformation. They co-founded Symplatform https://symplatform.com/, the international symposium for academics and managers working on platforms, and Platform Thinking HUB, the observatory where the innovation leader community can explore innovation through platforms. They are the authors of Platform Thinking – READ the past. WRITE the future, published by Business Expert Press in 2023. You can find out more about their work on platformthinking.eu https://platformthinking.eu/.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_public_corporations_by_market_capitalization

- Cusumano, M. A., Gawer, A., & Yoffie, D. B. (2019). The business of platforms: Strategy in the age of digital competition, innovation, and power (Vol. 320). New York: Harper Business.

- Katz, M. L., & Shapiro, C. (1985). “Network externalities, competition, and compatibility”. The American Economic Review, 75(3), 424-40.

- For a detailed analysis of the evolution of Amazon as a platform: Trabucchi, D., & Buganza, T. (2023). Platform Thinking: Read the past. Write the future. Business Expert Press.

- For a detailed analysis of Amazon evolution: Kenney, M., Bearson, D., & Zysman, J. (2021). “The platform economy matures: measuring pervasiveness and exploring power”. Socio-economic Review, 19(4), 1451-83.

- Rochet, J. C., & Tirole, J. (2003). “Platform competition in two-sided markets”. Journal of the European Economic Association, 1(4), 990-1029.

- Trabucchi, D., & Buganza, T. (2022). “Landlords with no lands: a systematic literature review on hybrid multi-sided platforms and platform thinking”. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(6), 64-96.

- Filistrucchi, L., Geradin, D., Van Damme, E., & Affeldt, P. (2014). “Market definition in two-sided markets: Theory and practice”. Journal of Competition Law and Economics, 10(2), 293-339.

- Trabucchi, D., Buganza, T., & Pellizzoni, E. (2017). “Give Away Your Digital Services: Leveraging Big Data to Capture Value”. Research-Technology Management, 60(2), 43-52.

- Farronato, C.; Denicolai, S. & Mehta, S. (2021). “Telepass: From tolling to mobility platform”. Harvard Business Publishing Teaching Case.

- Joachimsthaler, E. (2020). The interaction field: The revolutionary new way to create shared value for businesses, customers, and society. Hachette UK.

- Joachimsthaler, E. (2020). The interaction field: The revolutionary new way to create shared value for businesses, customers, and society. Hachette UK.

- Kominers, S. D. & Knoop C.I. (2020). “Klöckner & Co: Steeling for a Digital World”. Harvard Business Publishing Teaching Case.

- Trabucchi, D., & Buganza, T. (2023). Platform Thinking: Read the past. Write the future, Business Expert Press.