By Klaus Heine and Haibo Xue

Luxury brand management is identity–driven. Drawing on the concept of anthropomorphisation, Klaus Heine and Haibo Xue outline how to complement identity –driven with personality–driven branding; to create brand meaning in times of symbolic consumption, and how to start bringing your brand personality alive by answering five questions about the Big Five of Luxury Brand Personality.

Across virtually all societies, humans feel a need to anthropomorphise inanimate objects (Freling and Forbes, 2005). When asked to imagine a brand as a person, people show no difficulty in assigning human characteristics to brands as if they would describe other people. Brand managers often try to humanise their brands with anthropomorphisation techniques using brand characters, mascots, and spokespeople. Benefits include improved brand liking and closer brand–consumer relationships, which can even reach the level of brand love and ‘irrational’ loyalty (MacInnis and Folkes, 2017).

Paradoxically, anecdotal evidence suggests that many brand managers do not believe their brand to be people themselves, even though they may aim at creating anthropomorphised brands in the minds of consumers. For many brands, ‘brand personality’ still does not consist of more than a few traits that are used for brand personification (Freling and Forbes, 2005). Drawing on the concept of anthropomorphisation, the personality–driven approach to branding complements identity–driven brand management and takes it a step further.

What is Personality–driven Branding?

Personality–driven branding can be characterised by the following four main features:

1. The brand is seen as a person by everyone inside the company: The central idea of personality–driven branding is to enliven a brand internally in the minds of brand managers and company employees (MacInnis and Folkes, 2017). If managers aim to humanise their brand in the minds of their customers, first, they should start treating their brand as a person themselves.

2. The brand personality has her own free will, in line with the brand vision: One of the essential characteristics of humans is their free will. Therefore, to anthropomorphise brands, they must be seen as intentional agents – and their primary intention should be to pursue the brand’s vision. When the brand becomes a strong character, it can spark both the employee’s enthusiasm and the customer’s passion for the brand.

3. Thinking of the brand’s personality should evoke mental pictures comparable to consumers’ hold about real people: Instead of just with a few terms, the brand personality should be described sufficiently detailed to evoke a metaphoric mental picture about what kind of person the brand aims to represent: How does the brand personality look like? What are her/his personality traits? What is her/his lifestyle? By bringing a unique brand personality alive, marketers are creating a whole universe of symbolic meaning as a basis for brand differentiation.

4. The brand personality becomes the focal point of brand management: While brand personality is often considered as an independent concept that affects brands only in some peripheral and marginal way, personality–driven branding turns it into the main source of inspiration for brand–building and the focal point for brand management; guiding all branding and business decisions. Having in mind a clear mental picture of their brand personality, marketers could ask: How would the brand personality design a new product? How would s/he design a website or flyer? Karl Lagerfeld, for instance, does not imitate Coco Chanel’s style, but tries to understand her personality, take on the perspective of her ghost–soul and interprets her style and yet adapts it to modern times. The Chanel jewellery flagship store at Place Vendôme in Paris, for instance, was designed around the question: “In what sort of interior would Mlle. Chanel live today?” Designers used portraits of the founder, recreated her living room and some personal objects and as a result, the aura of Coco Chanel is clearly evident throughout the store (Dion and Arnould, 2011). When people inside the company align their actions by interacting with the brand personality, they are making the organisation seem acting as one person, which improves brand consistency. This can help reduce misunderstandings within the marketing team and especially in cooperation with external agencies.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

How to bring a Brand Personality alive?

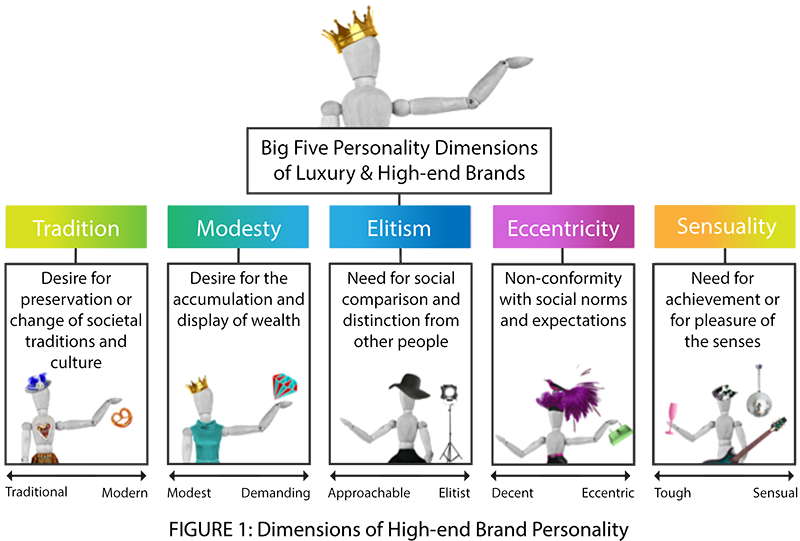

To bring a brand personality alive, it must first be described in detail, for instance, on the basis of the major brand personality dimensions. Based on a number of studies, five distinct personality dimensions of luxury brands were identified including tradition, modesty, elitism, eccentricity, and sensuality (Heine et al., 2018).

They capture the most important differences of possible brand personality characteristics in the luxury segment. Each of them reflects one of the key issues of the luxury segment: Tradition & culture, wealth & possessions, status & the role of other people, society & reference groups, and ambition & hedonism. Given that, many managers are inclined to find a lot of brand personality traits attractive, they can feel challenged to decide between them and are tempted to equip their brands with too many traits. As the dimensions of high–end brand personality are bipolar, brand managers are inevitably forced to decide between opposing traits to characterise their brand, which leads to more distinctive and consistent brand personalities. These Big Five dimensions can be thought of as five key questions about how brand managers want their brand to be. Each decision has a strong impact on the brand’s character and appearance. Answering the following five questions may help you develop a clear mental picture of your brand personality:

Question 1 – Tradition: Does your brand prefer preserving old–established traditions, heritage and culture, or is s/he rather open to progressive changes, reinventing society?

This dimension reflects a brand personality’s perspective on changes of tradition and culture in society. While a traditional personality looks much into the past as a source for inspiration, a modernist may rather refer to the present or future. While tradition is typical for many luxury brands such as Hackett and Rolls-Royce, it is still not an essential characteristic, which is proven by the success of modern brands such as Tom Ford or Richard Mille. However, while a traditional worldview contrasts with liberal ideas on society, it was found that it can still be combined with being open to new ideas, innovation and creativity. To account for that, Glisky et al. (1991) identified two independent dimensions of openness. The brand personality dimension ‘Tradition’ is closely related to one of them: ‘socio-political liberalism,’ the idea that society should be liberal, open, tolerant, experimental, progressive and individualistic.

Question 2 – Modesty: Does your brand represent a personality who desires being wealthy and owning or collecting beautiful and valuable objects? Or does s/he prefer a rather modest lifestyle?

Unsurprisingly, the desire for the accumulation and display of wealth is a major issue in the luxury segment. The demanding pole is related to traits such as aspiring, discerning and extravagant and corresponds to the human personality trait of materialism — the desire to accumulate possessions. Possessions can be accumulated to show one’s wealth through conspicuous leisure or consumption (Veblen, 1899) or to leave something behind (for instance, one merely looks after a Patek Philippe for the next generation). Symbols of conspicuousness include ostentatious logos and valuable materials such as gold and diamonds. Louis Vuitton appears to be the embodiment of a demanding brand. Whether in an ostentatious or more subtle manner, conspicuous brands typically represent the lavish and glamorous lifestyle of the ‘rich and famous’ depicted in the popular media. This is reflected by the motto of Mae West: “Too much of a good thing can be wonderful.”

The modest pole is related to being humble, moderate, frugal, down-to-earth and grounded and also idealistic, spiritual, intellectual, and philosophical. This is consistent with a rather simple or even ascetic way of life and with conscious instead of conspicuousness consumption. With a post–materialistic mindset, people may feel a desire for personal growth and self-transcendence and passion for some higher purpose in life. Typical examples for understated luxury include Bottega, Veneta, Loro Piana, Aman Resorts, and other forms of invisible luxury ranging from members–only institutions to the subtle aesthetics of Japanese Zen culture.

Question 3 – Elitism: Is your brand generally approachable and sociable or is s/he rather differentiating from others, staying within her exclusive circles?

Elitism refers to interpersonal aspects dealing with the role of other people and the need for social comparison and distinction. With an elitist disposition, the brand personality seeks status and exclusivity and is rather unapproachable to out–group members (who are not part of the target group), which is related to being reserved, distant, formal, refined, graceful, competitive, and authoritative. This can be symbolised by exclusive clubs and VIP areas.

The approachable pole, on the other hand, is related to heartiness, genuine joy, social responsibility, egalitarianism and to traits such as friendly, cheerful, cordial, considerate, trusting, generous, unpretentious, and outgoing. The post–modern ‘democratisation of luxury’ is limited insofar that luxury is by its basic definition not accessible by anyone at any time. Brands seen as elitist include Gucci and Rolex whereas benevolent brands include House of Dagmar and Ermenegildo Zegna. A study by Ward and Dahl (2014) suggests that brand desirability can increase under certain conditions when an aspirational brand personality is perceived as being unapproachable. However, a brand that is perceived as being too arrogant could cause a detrimental effect.

Question 4 – Eccentricity: Does your brand personality prefer conforming to prevailing social standards or is s/he ready to break the rules?

This dimension refers to a person’s level of non–conformity with norms and expectations of society and within her reference groups. Decent personalities prefer to respect hierarchy, to be discreet, polite and well–behaved in order to ‘fit in’ and to be liked and accepted. In contrast, non-conforming or even eccentric personalities prefer to ‘stand out’, be creative, and imaginative or even a bit crazy, provocative, and rebellious. The brand personality dimension ‘Eccentricity’ is closely related to the other of the two dimensions of openness identified by Glisky et al. (1991) capturing love for aesthetics, curiosity, fantasy, and unconventional views of reality.

While Hugo Boss appears to be the prototypical example for a brand that allows consumers to fit in, representative brands for the eccentric pole include Cavalli and Moschino. In order to gain an impression of the eccentric personality disposition, it helps to look at a picture of Salvador Dalí with his Colombian ocelot Babou. A central idea of luxury has been the self–determined use of one’s time and freedom from duties and limitations, which extends to non–conformity with social expectations (Veblen, 1899). As shown by Coco Chanel, Christian Dior and Yves Saint Laurent, who all broke the rules of their times, some ‘shocking’ and the freedom of ‘doing what you want’ is engraved in the nature of luxury brands. However, this freedom may be somewhat limited as the slogan by Audemars Piguet suggests: “To break the rules, you must first master them.”

Question 5 – Sensuality: Is your brand personality tough–minded and self–disciplined with a strong will to achieve her/his life mission or is s/he seeking enjoyment of life and pleasure of the senses?

This dimension refers to life goal–related aspects of brand personality and in particular to the level of strength to achieve ambitious goals and self–restraint from immediate gratification vs. sensuality and self-indulgence. Is your brand personality tough–minded and self–disciplined with a strong will to achieve her/his life mission or is s/he seeking enjoyment of life and pleasure of the senses? The tough pole is related to traits such as purposeful, ambitious, persistent, strong-minded, courageous, vigorous, active, dynamic, and energetic. On the other hand, the sensual pole refers to the pursuit of love, beauty and enjoyment and a happy and comfortable life, which is related to traits such as hedonistic, lighthearted, emotional, tender–minded, dreamy, sensuous and romantic. Archetypical representatives include entrepreneurs, creators and makers on the one hand and dandies, hedonists, gourmets and connoisseurs on the other. Hugo Boss is considered as a typical tough–minded brand and Jean Paul Gaultier as a typical sensual brand. This is reflected by their advertising, for instance, with a sharp–witted businessman giving interviews at a press conference versus a mystic princess riding on a rainbow with her unicorn.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Authors

Klaus HEINE (corresponding author) is Associate Professor of Luxury Marketing at emlyon business school, Asia and Co-Director of the High-end Brand Management Master Program at Asia Europe Business School in Shanghai. He holds a PhD from TU Berlin and specialises in high-end brand-building with applied-oriented research, education and practical projects with both, leading luxury brands and start-ups.

Klaus HEINE (corresponding author) is Associate Professor of Luxury Marketing at emlyon business school, Asia and Co-Director of the High-end Brand Management Master Program at Asia Europe Business School in Shanghai. He holds a PhD from TU Berlin and specialises in high-end brand-building with applied-oriented research, education and practical projects with both, leading luxury brands and start-ups.

Haibo XUE is Associate Professor of Marketing at East China Normal University and Co-Director of the High-end Brand Management Master Program at Asia Europe Business School in Shanghai. He holds a PhD from Shanghai University of Finance and Economics and, based on qualitative consumer research, specializes in high-end consumption rituals and brand management in emerging markets.

Haibo XUE is Associate Professor of Marketing at East China Normal University and Co-Director of the High-end Brand Management Master Program at Asia Europe Business School in Shanghai. He holds a PhD from Shanghai University of Finance and Economics and, based on qualitative consumer research, specializes in high-end consumption rituals and brand management in emerging markets.

References

- Dion, E., and E. Arnould (2011), “Retail Luxury Strategy: Assembling Charisma through Art and Magic,” Journal of Retailing, Vol. 87 No. 4, pp. 502-520.

- Freling, T.H., and L.P. Forbes (2005), “An Examination of Brand Personality through Methodological Triangulation,” Brand Management, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 148-162.

- Heine, K., Crener-Ricard, S., Atwal, G., and Phan, M. (2018), “Personality-driven Luxury Brand Management. Journal of Brand Management,” Vol. 25 No. 5, pp. 474-497.

- Glisky, M.L., D.J. Tataryn, B.A. Tobias, and J.F. Kihlstrom (1991), “Absorption, Openness to Experience, and Hypnotizability,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 60 No. 2, pp. 263-272.

- MacInnis, D.J., and V.S. Folkes (2017), “Humanizing Brands: When Brands seem to be Like Me, Part of Me, and in a Relationship with Me,” Journal of Consumer Psychology, Vol. 27 No. 3, pp. 355-374.

- Veblen, T. (1899), The Theory of the Leisure Class, New York, MacMillan

- Ward, M.K., and D.W. Dahl (2014), “Should the Devil Sell Prada? Retail Rejection Increases Aspiring Consumers’ Desire for the Brand,” Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 41 No. 3, pp. 590-609.