Big data versus quality information

‘Big Data’ is the new buzzword of today’s business world. Management consultants, corporate strategists and IT executives all ask the question: what to do differently in this new era of data abundance? As in the case of all buzzwords, there is a grain of underlying truth in the hype. Technological development and the Internet have created an environment where large amounts of data are easily available and so are the new tools to analyze it. As a result, for many, ‘Big Data’ is readily associated with the sophisticated execution of various data-mining techniques, usually carried out on the firm’s own transaction data. The hope is that such data-mining will uncover some hidden insights that can then be exploited for superior profits.

There are many examples of successful ventures that support this view. Google comes to mind immediately because, in some sense, it is purely about data mining. It consists of proprietary algorithms that process over 20 petabytes of data every day. Some of the algorithms organize – in real time – the structure of the vast amount of content available on the Internet. Some others run position auctions for thousands of advertisers bidding on millions of keywords. One of Google’s key strengths is that its algorithms evolve over time based on the feedback coming from its users’ behaviour while they are using Google’s services. This fuels a positive feedback loop. As a result, Google’s core competitive advantage resides in its mastery of data mining on vast amounts of transaction data. While Google is probably the purest information business on Earth, many other companies from retailers, banks, telecom companies and airlines have the opportunity to learn about their customers, markets and operations from the vast amount of transaction data that they process every day.

But is it really the abundance of data that poses the key challenge (and opportunity) for businesses? While ‘Big Data’ is certainly a headache for the IT department, I would argue that the question top management should really ask is: how should the company be run in an environment where, increasingly, it is information and knowledge (and not traditional material resources) that represents the scarce input for value creation. The question to ask is: what do I need to know to create more value than my competitors? Once I know the answer to this first question, then I can ask: where can I acquire the necessary information to get it? The answer might very well be in data-mining but under this new perspective the firm can search for information in a much broader ‘market,’ combining very different information sources. In fact, this is what Google does. Its algorithms rely on a variety of insights and information sources. What guides their development is a simple question focused on Google’s core value creation process: how can one provide the most relevant link(s) to a given search word?

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]In sum, there are two key insights that – I believe – need to be remembered in this new era of unprecedented wealth in data, information and knowledge. First, that having superior information than competitors’ is indeed more important today; competitive advantage increasingly originates from superior information about various parts of the business environment. Second, superior information does not necessarily come from the firm’s own data; in today’s information rich environment it is imperative for firms to seek data sources from external ‘information markets’ that have become extremely developed in recent times. “How to use information markets?” is the relevant question for value creation and competitive advantage. One of the key challenges for businesses today is to get familiar with these markets, which present many pitfalls for the uninitiated.

Information Markets

Whether we want it or not, in today’s world, we are all heavy users of information markets and, on occasion, we also contribute to the creation of information either voluntarily (e.g. by commenting a blog post) or involuntarily (e.g. by carrying out a search on Google). Indeed, information markets are everywhere in today’s societies yet we know relatively little about their functioning. We know certainly less than what is justified by their prevalence in our modern lives. This is partly true because the intangible nature of information makes it hard for us to see it as a product or commodity that responds to the traditional market forces. Moreover, information markets do behave in ‘strange’ ways, even if one submits them to thorough economic analysis. So let us define better what an information product is and uncover some of the peculiarities of information markets.

It is useful to define information products with three core characteristics: (i) they are digitizable, (ii) they are used for decision making and (iii) the decision maker pays for them. Financial data, market research, expert opinions of various kinds are good examples and represent services worth hundreds of billions of dollars in sales. Some examples are more difficult: Google’s search results (for which one pays by viewing unsolicited advertising), consulting services (where one can argue about the extent to which they can be digitized) and medical diagnosis (that is often coupled with non-information services, e.g. treatment). And, there are also many counter-examples that common language calls “information”: advertising (not paid for by the decision maker), entertainment (not used for decision making), etc.

If we accept the definition then we can easily describe the information industry’s value chain as figure 1 below:

The key point of this simple description is that data, information and knowledge represent a continuum, whereby more and more value is added for the decision at the end of the value chain. More value comes from more ‘structure’ and different information vendors have core competencies that add value to the decision in different ways: some are good at gathering accurate data, some others do great statistical analysis to discover relevant patterns in the data and yet another group of firms may be good at discovering causal links explaining various empirical patterns. There are many subtleties in this view of the world but it gives an idea of the main suppliers and how they create value. Let us next look at customers.

Imagine that I am a decision maker and I try to acquire information from competing information sellers. What product features will I care about? To answer this question one needs to realize that decision making consists of choosing among alternatives under uncertainty. When we chose from alternatives, the issue is that we are not sure what their respective value really is. Information can help reduce this uncertainty. As such, a key characteristic that we will care about is the reliability of information. Second, the beauty of information markets is that we can gather information from different sources and combine these to improve our decision. If we do so we need to make sure that the sources are independent (who wants to collect the same information twice?). So independence is also a core characteristic of information products. Finally, we certainly care about the price of information. There are a few other characteristics that may matter but let us stop here for a minute and explore how a decision maker choses information providers and what this implies for the market price of information.

Substitutes, Complements and Biased information

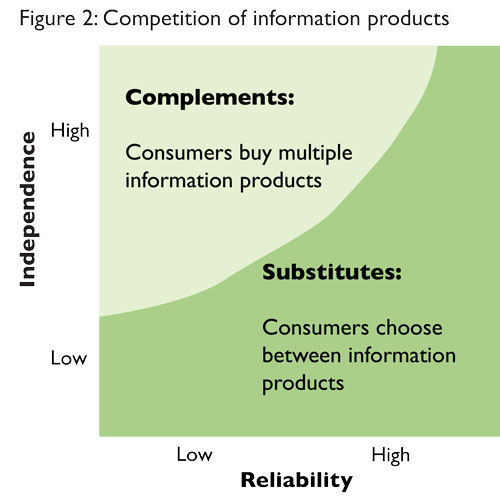

Imagine that you are buying information from two symmetric sellers, whose reliabilities are identical. Essentially, we assume that reliability depends on the environment and not the information suppliers. To be more concrete, assume you consider buying market research to predict the demand of a new product. If the product is an extension in a familiar market, both research firms will do a reasonable job. If it is a totally new innovation and you consider a new market, the research firms will both have an unreliable forecast. The different scenarios you can face are summarized in figure 2.

Let us explore different regions of this product space. On the lower side of the square, the products are correlated (say the research firms use similar sources and methodologies), and you will only purchase from one of them, presumably the cheaper one. Similar is the case when both information sellers are reliable (on the right side of the square). You do not really need two reports in this case because one gets you close enough to a good decision. The reports are substitutes. But consider the upper left corner of the figure, where both firms are unreliable but they are independent. In this case, one report is of little value but two of them would help you get to the truth because their independence guarantees that pooling their content improves your estimate significantly. In other words, in this case, the information products are complements rather than substitutes. This dynamic has important implications for the price of information. When information products are substitutes, prices will be low as the sellers will undercut each other to get the sale. This is likely to be the outcome when information is reliable and/or sellers have correlated sources or similar methodologies. When information products are unreliable and independent however, then they are complements and information sellers will raise their prices since they know that consumers are likely to purchase both products together. Let’s pose for a minute: here we are in a situation where competitive markets lead to low prices for reliable information and high prices for unreliable information.

This simple model has far-reaching implications for the strategies of information sellers. First, it is clear that if you are in the business of selling information it is much better to be in a highly uncertain environment. This is much more likely to be the case for categories at the higher end of the value chain. Selling data in a competitive environment is tough (no wonder data vendors are in a bitter price war now that the Internet makes it easy to deliver their products). But selling an opinion is easier because different opinions are more likely to complement one another (this is why market research firms enjoy solid profits and often serve an overlapping customer base). Moreover, one can show that in such environments, firms are actually better off with a competitor than being a monopolist, so inviting some competition might not be a bad strategy. Notice also that if prices behave this way then information sellers have an incentive to tell their customers that their products are “unreliable”, essentially, teaching customers that they need multiple information sources. This is tricky and in practice it has to be done in a subtle way, emphasizing the uncertainty faced by decision makers rather than the reliability of suppliers. Information markets are strange indeed!

There are many other characteristics of information and knowledge markets that today’s businesses need to be aware of. In fact, the situation described above is not that disturbing for information buyers (other than the fact that they have to pay dearly for multiple unreliable information products), because at the end, one way or another, they get closer to the truth. It is more of an issue for the sellers of information who need to follow unorthodox competitive strategies. Indeed, so far, we have assumed that information sellers were ‘unbiased.’ In other words, we assumed that they always told their best estimate of the truth. ‘Unreliability’ was not their ‘fault’ but that of the environment. But competition between information sellers may actually push them to lie and report biased information, and this has a major impact on the decision makers who use the information. When might this happen?

‘Bias’ is not trivial to define. Two experts (say, two doctors) may reach different conclusions looking at the same data (say, a set of tests and lab results). We can call this bias but this type of bias may be good for the decision maker (the patient) who is seeking a second opinion. It is more appropriate to define bias as the expert reporting something different from her true belief. This is clearly bad for the buyer of the expert’s opinion/information. There might be trivial reasons for experts to be biased. So-called ‘partisan bias’ is a well-known case: it occurs when the expert has an interest in the decision of the buyer of information. In our example, the doctor might have an interest in over-diagnosing the patient if it is likely that he will also be commissioned to perform the treatment. This is why one should always take the advice of a car mechanic with a grain of salt. One would believe however, that bias should disappear with competition and, actually, this is the case for partisan bias. Yet, there are situations where bias may actually be caused by competition.

This is the case, for example, when the information sellers compete in a contest. This often happens in the world of finance where analysts compete to become the most accurate forecasters of the performance of various securities or values of key macro-economic figures. Often, there are former contests for analysts where a disproportionate reward goes to the best performers. One of the side-effects of such contests is that they create peculiar incentives. Why? A forecaster always faces a dilemma: it has to weight his private information (essentially, the insight that s/he gained from his/her proprietary analysis) and the common wisdom that is publicly shared by all experts (what we call consensus forecast). However, in a contest, it is not only important to be a good forecaster but it is also beneficial to be the ‘only’ good forecaster. It pays off to position oneself away from the others. As such, one can show that, in a contest, it is perfectly rational for the forecasters to overweight their private information and ignore the common wisdom. This behavior in turn creates bad forecasts.

The opposite happens when experts compete for their long-term reputations. This also happens often in the real-world. Credit rating agencies are a good example in case. Here, what matters to the information provider is to be close to the truth on average and it is really risky to be far off from everyone else. Even if one is wrong, as long as everyone else is wrong the forecaster’s reputation is not too tarnished. The result is that forecasters ‘shade’ their opinions by overweighting the common wisdom and ignoring their private information. This leads to the well-known phenomenon of ‘herding’ where all experts tend to say the same thing with the consequence that decision makers tend to all make the same mistakes. The role of credit rating agencies in the recent financial crisis can be partly explained by these incentives. Together, these examples show that one needs to be careful when using information markets. Depending on the nature of competition between information sellers the reliability, biasedness and price of the same information might be very different.

Conclusion

It is often claimed that we live in an information age. This has many implications for decision makers in general and business leaders in particular. For most businesses nowadays, increasingly, it is superior information that is at the origin of competitive advantage. The prime challenge in this new environment does not start with data analysis. Rather, the most important issue for the firm is to understand its information needs: what information, if it were available, would make a real difference for value creation and competitive advantage? Once the answer is clear to this question then finding information is not that hard. It is important however, that the firm doesn’t constrain itself to its own information. Indeed, in the last decades, information markets have become ubiquitous and provide opportunities way beyond the analysis of the firm’s own data. However, being effective at identifying the right information sources, understanding information suppliers’ incentives and combining various, often qualitatively different sources efficiently is quite challenging. While there is little guidance readily available from the standard sources of business education, an increasing body of literature works on discovering the rules of information markets for the business world.

About the Author

Miklos Sarvary is the GlaxoSmithKlein Chaired Professor of Corporate Innovation at INSEAD. He is also the Deputy Dean of Executive Development Programs and Director of the INSEAD Learning Innovation Center. His research focuses on the Media industry with a recent focus on new media and user-generated content. His long-standing work on information and knowledge markets has been recently published in Gurus and Oracles: the Marketing of Information, MIT Press.

Before joining INSEAD, professor Sarvary was a faculty member at Stanford University and the Harvard Business School. He has taught or consulted for many large corporations including, McKinsey & Co., IBM, Schlumberger, Nokia and Samsung among others.

![Deconstructing the Myth of Entrepreneurship iStock-2151090098 [Converted]](https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/iStock-2151090098-Converted-218x150.png)