By Guido Stein and Alberto Barrachina

To build agile organizations you must understand human relationships

1. Change> Transform Your Approach to Transformation

This technical note explores some aspects of management and organizations in an era that has been called “a constant state of transformation.” In fact, we may have waited too long to start the process of transformation, and now is the time to modify our approach. We need to put people first, and approach digital technology from the perspective of reality, beyond merely a digital or virtual reality.

Management should focus on helping people connect with what they do and develop a strong sense of purpose, encourage them to give it their all, provide them with what they need in their professional journey and build a culture of constant learning, while also ensuring that leadership keeps up with the times.

Since the future is decided by our actions today, there’s no time like the present to renew the ways in which “individual + team x organization” operates. Perhaps we should adopt the idea of distributing power and simplifying the organization as general criteria, with a helping of flexibility to respond quickly to client and employee needs in a market and environment that are “always in transformation.” The logical next step is a culture of agility.

The present technical note is based in this context to address the following questions: How are organizations and work methodologies changing? And how are agile companies implementing these changes?

2. Change Is Already Here

Some stories repeat themselves. The multimedia product development teams of a telecommunications company, working with the help of a small group of consultants, began to grow from 2012, following a rise in market demand for their products. At that time, the working groups did not use any clearly defined development processes; the only specifications came from commercial management, which assigned the functions and deadlines for delivering the product to the customer. The teams worked as they thought best, and although development was chaotic, product specifications were accomplished on time. However, as the organization began to grow, there was a need for a more orderly process that would reduce the time needed to launch a product to the market. As demand increased, new competitors appeared and delivered products quickly, at very competitive prices. The company was unable to reach all of its potential consumers due to these inefficiencies: development deadlines were longer and difficulties arose in completing the required specifications. Employees became very stressed.

There is no doubt that such dynamism and rapid market changes are causing companies to worry about their agility in adapting to external threats and opportunities. The competitive advantages of companies are less lasting, due to the introduction of new and disruptive technologies that create new business models; globalization and digitization of the market, which increase the imbalance between large and small economic powers; and the trend towards massive homogenization of both production and consumption.

Change is clearly essential, but what should change look like? According to an Accenture study, 63% of companies anticipate their industries will face radical change, accentuated by digital trends, while 44% show signs of being susceptible to future disruptions. However, less than half of the companies that undertake organizational change are satisfied with the results.

Companies that are structurally solid and have a healthy balance sheet have often been optimized by efficiency improvement processes rather than by increasing strategic agility. At the same time, internal difficulties can grow, such as a lack of clear strategic direction or a lack of alignment between business objectives and transformation, problems related to project management, the search for definitive solutions, unproductive meetings, excess documentation, poor talent management, complacency in traditional forms of working, or resistance to organizational change. It seems that the hierarchical structures and organizational processes that have been used for decades to manage and improve companies are no longer up to par in a world that is moving faster and faster.

Empirical evidence shows that excessive hierarchy and bureaucratization limit companies’ ability to exploit the maximum potential from their workers, so looking for activities that really generate added value and drive transformation makes sense. The knowledge acquired by workers, and their consequent employability, are companies’ fundamental legacy in facing this transition towards more agile organizations, which need more than ever to be innovative in order to remain competitive in the market. Repetitive and automatable tasks will soon be done by machines. By automating work, it is possible to free up capacity in the employee, who functions as the “brain behind the work”.

From Pyramidal to an Agile Organization

The Pyramid Structure

The classic organization is based on a flowchart with a pyramidal, hierarchical, static structure, distributed in silos, where decisions are made at the top and flow downwards. The operation is like that of a machine, a series of connected parts that follow a logical order so as to repeatedly produce a result. Employees perform routine tasks with pre-defined roles. There is a sense of organizational order and control in a stable and predictable environment.

In this structure, successful managers develop linear planning and maintain supervision through standardization of processes and bureaucratization of the organization. The basic structure is stable, but often stiff and slow. The managers located in the middle of the pyramid, middle managers, are responsible for transmitting top management decisions to the rest of the organization and managing daily work. At the base of the pyramid are employees, responsible for generating value for the customer and transforming ideas into tangible goods and services.

A hierarchical and bureaucratic structure creates a rift between managers, who make decisions and give orders, and employees, who apply such decisions, wasting employee potential for proposing new initiatives at work or approaching problems from different areas and business units. Classic procedures of company culture can slow down its operation, such as preparing reports with a high level of abstraction, creating new levels of managers that significantly reduce the interaction between employees or, on the part of superiors, simplifying analysis and project evaluation.

Coordinated Anarchy

In today’s rapidly evolving environment, companies must face the challenge of creating organizations that both innovate and operate efficiently. Three quarters of respondents to a McKinsey survey stated that business agility was a priority for them, but less than 10% stated that their company had implemented an agile transformation in its corporate center or in its divisions. The transition to an agile organization often comes up against unspoken assumptions about “how we do things in our company”.

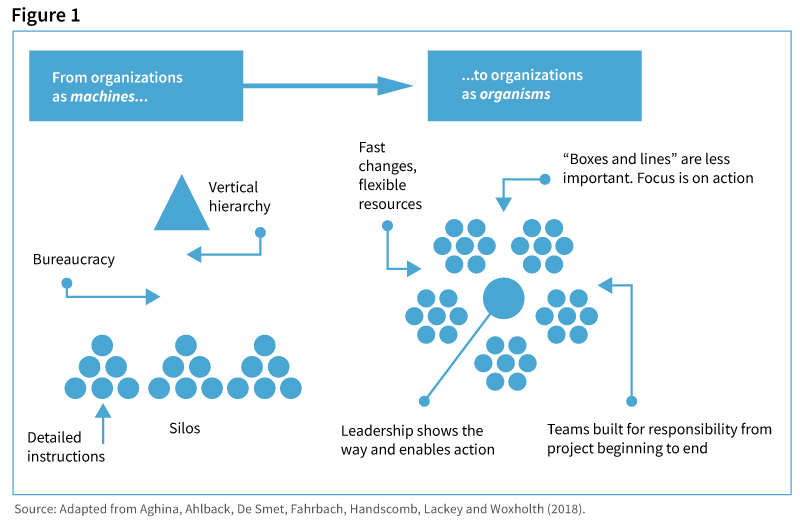

The trend points towards transformation from machines with standardized processes towards more dynamic organisms (see Figure 1). The Taylorist organization strove to increase productivity through the mechanization and specialization of work and the people who did it. Taylor expected workers to be as safe, predictable, and efficient as the robots that have now replaced them (Morgan, 1985). Under the weight of the mechanical metaphor, organizational theory is centrally concerned with the relationships between objectives, structure and efficiency, running the risk of isolating itself from its environment.

The evolution towards the concept of an organism visualizes the company as an open system that develops a process of adaptation to its environment; to survive in the market, it offers integrated responses that meet the multiple needs of customers. An agile organization also has a sustained ability to respond quickly and effectively to internal or external changes, while continuing to obtain satisfactory results on a sustained basis. Responsiveness is produced by quickly adapting to dynamic customer needs. The network of teams that embody organizational agility work autonomously, in short cycles and therefore with rapid learning and decision-making leveraged on the latest technology. The novelty largely comes from the fact that team and member roles and responsibilities are not defined until the beginning of the project, and the most outstanding feature of this method is anarchic and coordinated self-management.

When the organization breaks down into small, highly autonomous units, people are forced to take direct responsibility for the results of their work, and this encourages them to improve in commitment, performance and the contribution of their micro-business to the company’s overall health.

To understand the genesis of the new model, it’s worth revisiting the Agile Manifesto of 2001, which defined an alternative to classic software development, based on the waterfall model.

4. Two Sides of the Same Coin: Waterfall vs. Agile

The Waterfall Model

The waterfall model is a cascade development with a structure made up of the following phases: initiation, planning, execution, monitoring and closure. Roles are defined hierarchically by a project manager, who represents authority. Pre-project planning is agreed between the supplier and the client. A list of requirements that the final product should have is defined, a delivery date is established, resources are assigned and costs are agreed in a contract. The development of the project is sequential: each phase must be completed one hundred percent before starting the next. In principle, the design is not subject to modifications by the client until it has been delivered.

In environments characterized by technological complexity and strong innovation, this model presents a rigidity that is unacceptable for today’s customers, who want to make changes or examine the product during its development. Changes are often lengthier to implement after all stages of development are closed, and therefore costlier. If requirements are not clear from the beginning, the model is ineffective. Testing and reviews are done at the end of development, increasing the probability of unfulfilled expectations and difficulty making adjustments.

The Agile Model

In 2001, experts from various software development programs met in Snowbird (Utah, United States), where they examined empirical evidence confirming that the waterfall model was not suitable for highly disruptive scenarios, mainly because its lack of flexibility. They decided to found the Agile Alliance and created the Manifesto for Agile Software Development to provide precise agile solutions for project execution, specifically software creation. They decided that the budget and the times agreed between the agile team and the client would guide the development of the project until its final delivery. The manifesto was committed to “individuals and interactions vs. processes and tools, software running vs. technical documentation, collaboration with the client vs. contractual negotiation, and response to change vs. following a plan@. In more detail:

- Individuals and interactions vs. processes and tools. The processes and tools offer significant value to the work teams in the development of the projects. On their own, however, they do not create value for the end customer: they require teams of motivated and talented people, and effective management.

- Software running vs. technical documentation. When the client acquires software, in most cases it incorporates the extensive technical documentation necessary for the user to start operating. However, this documentation may not offer any added value, due to the fact that the final software turns out not to be useful for the customer. If, on the other hand, the provider makes sequential deliveries to the customer during the development of the software, they will have the certainty that the software is being developed correctly and the guarantee that the product will provide what is needed.

- Collaboration with the client vs. contractual negotiation. Contracts are an essential element to establish a relationship of trust between the supplier and the customer. Despite this, friction between the supplier and the customer can arise when the latter requires an improvement which does not appear in the contract specifications. If, from the first moment, there is collaboration and a search for effective solutions between both parties, and this is specified in the contract, agility will protect the contractual relationship.

- Response to change vs. following a plan. Preliminary preparation of a strategic approach and sequential product development is necessary for final delivery to the customer. Not all plans work out however, and some goals may not be met. But if plans are adapted according to client circumstances and requirements throughout the process, there is a correlative increase in the chance of success.

It wasn’t easy for traditional managers to understand or implement the new paradigm, in part because it came from IT, which tends not to feature strongly in traditional organizational management hierarchies; and in part because of the illusion that new technologies alone will solve the challenges of digital transformation, when in fact competitive advantage does not arise from the technologies themselves, but from the capacity of the organizations of quickly understand and adapt technology to multiple customer needs. There were also issues applying the agile concept to environments that demand a small degree of innovation with less uncertainty.

5. Agile Organization’s essentials

Three common characteristics of the agile philosophy can be identified from an analysis of companies that have introduced it:

- The development of small, autonomous, cross-functional teams, with a high degree of interaction between them, that receive constant feedback from the end customer. They can be designed as responsible for a development project from start to finish, or transversal teams, with coordination between members of different autonomous teams who share the same function. These teams may be within the organization, in charge of final delivery of the product; or they can be composed of freelancers – designated workers who perform a specific task part – or full-time.

- The focus on the customer and adaptation to the environment: continuously delivering greater value, knowing the customer’s point of view, quickly adjusting offers and production methods, and even business models, in order to satisfy market demands. This requires a degree of agility that the hierarchical bureaucracies that prevail in most organizations cannot offer today (Hamel, 2009). During the past decade, a large part of companies’ restructuring efforts have been aimed at alleviating this organizational and management situation.

- The creation of a network of high-performance teams that decides to work in an agile and fast way. The introduction of the network into a traditional structure can be done through a dual organization. The dual configuration permits, on the one hand, the existence of a “strategy acceleration network”, made up of agile teams, and, on the other, a hierarchical system guided by the organization. In the initial phase of transformation, the acceleration network is usually made up of between 5% and 10% of employees, mainly volunteers. These teams work outside the bureaucracy and controls surrounding organizational decision-making. The hierarchical system is responsible for the efficiency and reliability of the processes, approving budgets, compensation and metrics, and supervising the resolution of generic problems.

Implementing agility

In 2020, 76% of companies in Northern European countries considered that agile projects would come to outnumber waterfall projects. The technology, telecommunications, financial services, media and entertainment sectors are leading this change in Europe. These sectors have the right conditions to adopt strategic agility, which helps them to be flexible and to adapt and respond quickly to market changes and alterations. These conditions are categorized along two main axes:

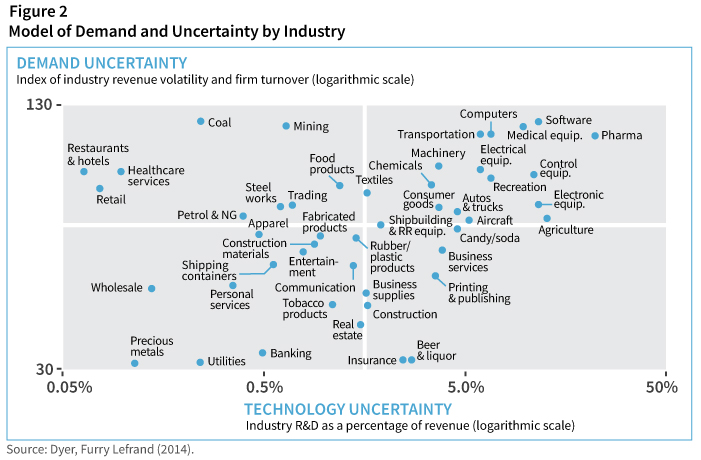

- A high degree of sectorial uncertainty and innovation in the market. The kind of environment the sector is currently in is worth evaluating: if it is complex and highly uncertain or if, on the contrary, there is stability that allows reasonable predictability regarding its evolution. According to the Stacey complexity matrix (see Figure 2), the complexity of a sector can be defined using a diagram that presents two main variables: the first (horizontal axis) is the uncertainty of demand, which involves additional unknowns associated with the resolution of problems, such as customers’ hidden needs or preferences. The second variable (vertical axis) plots technological uncertainty, referring to the technologies that could emerge or combine to offer new solutions. The accumulated evidence indicates that promoting agile behavior is recommended in environments with high sectorial uncertainty.

On the horizontal axis, technological uncertainty is measured by average R&D expenditure relative to the percentage of sales in the industry during the last ten years. On the vertical axis, the uncertainty of demand is measured by the volatility or change in the industry’s income in the last ten years and the percentage of companies that entered or left the industry during that same period of time.The industries with the highest level of uncertainty are medical technologies and equipment, computers, software development, pharmaceuticals, and measurement and control equipment. For both healthcare and software companies, the scenario is more complex due to the emergence of new challenges, technological progress, and innovation in goods and services. On the other hand, in restaurants and hotels, technological uncertainty is lower, but uncertainty of demand is high due to previously latent new customer preferences, among other factors.The industries with the highest level of uncertainty are medical technologies and equipment, computers, software development, pharmaceuticals, and measurement and control equipment.

On the horizontal axis, technological uncertainty is measured by average R&D expenditure relative to the percentage of sales in the industry during the last ten years. On the vertical axis, the uncertainty of demand is measured by the volatility or change in the industry’s income in the last ten years and the percentage of companies that entered or left the industry during that same period of time.The industries with the highest level of uncertainty are medical technologies and equipment, computers, software development, pharmaceuticals, and measurement and control equipment. For both healthcare and software companies, the scenario is more complex due to the emergence of new challenges, technological progress, and innovation in goods and services. On the other hand, in restaurants and hotels, technological uncertainty is lower, but uncertainty of demand is high due to previously latent new customer preferences, among other factors.The industries with the highest level of uncertainty are medical technologies and equipment, computers, software development, pharmaceuticals, and measurement and control equipment. - The client’s level of collaboration and involvement. The customer, as a user, is able to check the progress of a product in its different phases, offering a relevant assessment of awareness of requirements to be met in each of them. However, for companies, constant interaction with the customer and their ability to examine work in progress can be an added cost, often unaffordable. Identifying the type of project and the client, and deciding if it would be better to approach it another way, has become the first variable to consider. Agile is, after all, a means to an end, and as such it must adapt to what it is intended to achieve.An example of a company that meets these two conditions is Spotify. In 2008, it implemented agile management with small autonomous teams that sought to offer constant value to the client. The focus of these teams is to constantly meet user needs and to analyze experiences with the product. In 2015, after seven years of innovation in the on-demand audio streaming sector, dedicated to broadcasting audio in real time without downloading it, the company developed a new functionality: Discover Weekly, a list of recommended songs that renewed weekly. During its development, prototypes were quickly launched and tested by Spotify users, who contributed numerous ideas and approaches to product improvement. One of the experiments was large-scale, involving 1% of users – more than a million at the time. About 65% of respondents found a new favorite song to add to their list. It was a resounding success and Spotify attained a competitive advantage over competitors such as Apple Music, SoundCloud and Pandora in a sector characterized precisely by a high degree of uncertainty and innovation.

Agility and Growth

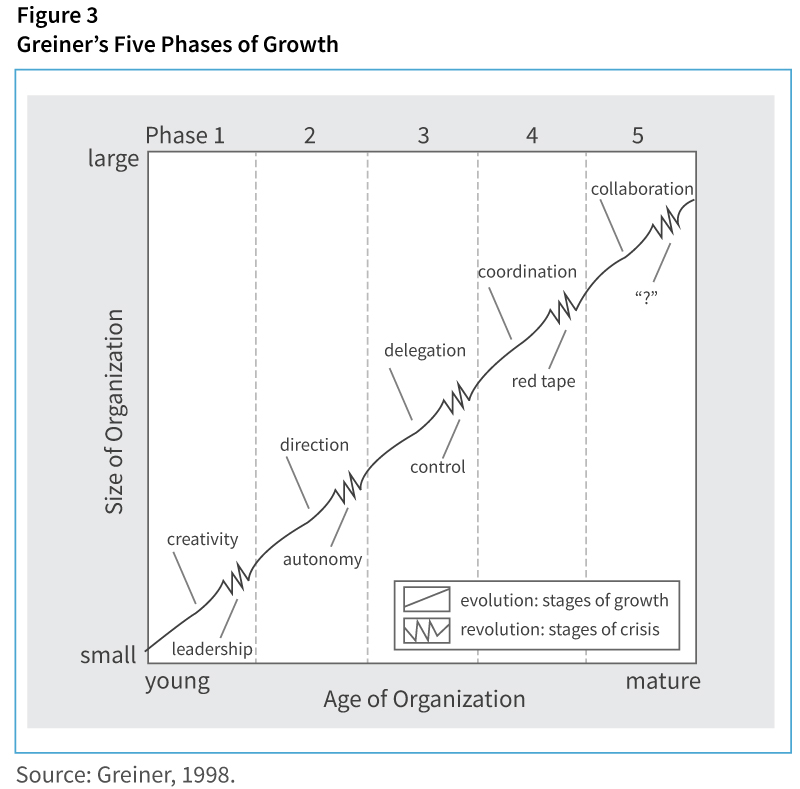

The predictive Greiner model defines the main dynamic capacities that allow for a response to the next crises in different phases of growth (see Figure 3). In the initial phase, the company shows great creativity in developing the business model and strategy; this stage is characterized by high levels of effort and few obtained results. Problems such as lack of team coordination, lack of unanimity in strategic direction, lack of time pressure to achieve objectives or limited experience in certain areas often arise in this phase, which requires a strong leadership presence to overcome.

In the second phase, leadership replaces the stellar role of growth. This phase is usually characterized by sustained development with a functional structure; efficient capital and debt management, incentives and budgets; and the standardization of processes. According to Greiner, the crisis will come due to the lack of autonomy among the managers who are below the steering committee and who will demand greater power in decision-making.

The third phase aims at growth through the delegation of decisions and their execution. It is characterized by a decentralized structure, supported by the responsibility of those who operate or are close to the market. The crisis may come from the steering committee, which feels that it has lost control and supervision of the organization, but knows that it cannot return to the previous centralized system.

The fourth growth phase takes place through coordination and supervision management. The roles and responsibilities of managers and work teams are reviewed, functional support is centralized and the work teams themselves are held responsible for return on investment (ROI). Excessive supervision can lead to a bureaucratic crisis.

In the fifth phase – growth – collaboration replaces supervision. Control mechanisms are simplified; cross-functional work teams, advanced information systems and growth incentives are created; and a decentralized support staff is organized.

The application of the agile model can be carried out in each phase. However, its viability varies: in the first phase of creativity, implementing agile will be less complicated due to the size of the company and the absence of an operational culture. As the organization grows and establishes new structures based on the control and regulation of processes, strategic agility will be more complex to implement, due to the hierarchical and bureaucratic organization.

Managers who desire an agile approach must strive to delegate work and power of autonomy to lower levels of the organization. The priorities will be to define a strategy with clearly identified objectives, coordinate the work teams in a cross-functional way, establish advanced information systems and eliminate all supervision and bureaucratization that is not essential. Proposals for new agile policies and procedures in the company are not enough to modify the organizational model. It is necessary to transform organizational structures, functions and management practices, planning systems, budgets, incentives and the measurement of results that have established the organization’s status quo for many years (Hamel, 2009).

Addressing Change

When addressing changes in the organization, management requires self-awareness to understand that change is a multifaceted process that will always be longer and more complicated than anticipated, with conflicting interests and peaks and valleys of uncertainty. Haste and precipitation are not forgivable: both are sources of avoidable mistakes.

Cases described as successful usually occur when employees discover that change must happen, that things cannot continue the same as always, often through being forcibly confronted with realities negative to company performance: new competitors, a reduction in margins, decreases in market share, lack of growth in income, relevant indices showing a drop in competitiveness and, above all, losses and layoffs. At such times, everyone understands that maintaining the status quo is a greater risk than jumping into the unknown (Kotter, 1995). There are studies that indicate that the message will be effective if at least 75% of employees consider that the current operations of the company are unacceptable.

The next step, says Kotter, is to build a strong coalition. Initially, a strong team is required to guide the transformation. Empirical evidence suggests that success is not usually led by senior managers, but by people with experience, information, reputation and good relationships in the company (Kotter, 1995), who add extraordinary energy and ambition. In small and medium-sized companies, this team is usually made up of between three and five people, while in large companies the number usually ranges between twenty and thirty, sometimes reaching much higher figures.

Before making any changes, managers must identify and address roadblocks. Such blocks can appear in the organization’s own structure, such as certain categories of tasks that prevent people achieving greater productivity. If there are routine tasks that a machine can do, waiting for automation is risky. On the other hand, it forces managers to focus on jobs where people can give their best self. If there are employees who themselves present roadblocks, they should always be treated fairly and considerately, but be made to understand that if they do not change, they will need to be changed. If transformation processes don’t yield results within months or just over a year, they are often abandoned. However, experience suggests that it is after the first year has passed that sustained improvements in productivity, or higher recurring rates of customer satisfaction tend to be seen. If you want to see rapid progress, you should create a culture of short cycle earnings. This allows you to maintain a level of urgency within the organization without losing sight of the medium and long term, which is where the strategy resides.

The most important challenge is to maintain the need for improvement with the second and third changes so as to eventually create a culture of continuous and incremental change in which the most important decision is the next decision, not the one that has just been made. For this, the agile model can be your best ally.

Don’t Let Your Agile Culture Making you Vulnerable

The culture of agility fosters continuous learning and an expansion of creativity, thanks to leadership that is focused on people and their development. The operational result is agile learning and decision cycles.

The best organizational agility must be based on stability, and that means it must be compatible with some basic human needs. Psychiatrists like Marian Rojas recommend learning to live in a routine, in waiting, because when we only depend on strong emotions, changes, intense experiences and feelings in the short term, we become too vulnerable; in fact, most of what we are concerned about will never happen, but our body and mind experience those possibilities as though they were real, because they do not distinguish what is likely to become reality from mere fiction. In turn, we have never had so much access to information, and in turn we have never been so vulnerable to deception, because we have fallen in love with the superfluous. In the age of agile transformation, you also need agility to stop and think.

About the Authors

Guido Stein is a Professor in the Department of Managing People in Organisations and Director of Negotiation Unit. He is partner of Inicia Corporate (M&A and Corporate Finance). Prof. Stein is a consultant to owners and management committees of companies. Member of The International Academy of Management and the International Advisory Board MCC (Budapest) and is a collaborator with People and Strategy Journal, Corporate Ownership & Control, Harvard Deusto Business Review, The European Business Review and Expansion. Prof. Stein’s books in English include “Managing People and Organisations: Peter Drucker’s Legacy”, “Now What? Leadership and Taking Charge” and co-author of “Keys to Leadership Success”. He is now working on a book, “Ambidextrous Negotiator” with Kandarp Mehta.

Guido Stein is a Professor in the Department of Managing People in Organisations and Director of Negotiation Unit. He is partner of Inicia Corporate (M&A and Corporate Finance). Prof. Stein is a consultant to owners and management committees of companies. Member of The International Academy of Management and the International Advisory Board MCC (Budapest) and is a collaborator with People and Strategy Journal, Corporate Ownership & Control, Harvard Deusto Business Review, The European Business Review and Expansion. Prof. Stein’s books in English include “Managing People and Organisations: Peter Drucker’s Legacy”, “Now What? Leadership and Taking Charge” and co-author of “Keys to Leadership Success”. He is now working on a book, “Ambidextrous Negotiator” with Kandarp Mehta.

Alberto Barrachina is a Business Intelligence Analyst at PowerShop in Madrid, Spain. He is highly costumer-oriented, multitasking and results-driven, empowered by an international and entrepreneurial mindset, and with a sincere passion in business intelligence, content strategy, and digital business strategy. He is a research analyst who’s been collaborating with Professors Guido Stein and Kandarp Mehta.

Alberto Barrachina is a Business Intelligence Analyst at PowerShop in Madrid, Spain. He is highly costumer-oriented, multitasking and results-driven, empowered by an international and entrepreneurial mindset, and with a sincere passion in business intelligence, content strategy, and digital business strategy. He is a research analyst who’s been collaborating with Professors Guido Stein and Kandarp Mehta.