By Jim Dewald

Jim Dewald discusses the processes towards corporate entrepreneurship which are needed for organisations to achieve longevity and success in the evolving market.

I find it fascinating that corporations are inherently capable and sufficiently resourced to succeed in entrepreneurial ventures – they have the money, the ideas, the brainpower, the leadership capabilities, the sales channels, the suppliers, the research facilities, the customers, the status, and so on. In short, existing corporations already have almost everything an individual entrepreneur seeks in the pursuit of success. So why isn’t there more corporate entrepreneurship? It is because corporate entrepreneurs face institutional barriers, which include rigid strategic plans, risk-adverse decision-making processes, rules that restrict behaviours, and a low tolerance for failure both within the firm and within society. Organisations have the capabilities and resources, but they lack the processes necessary for corporate entrepreneurship. This can be fixed.

The stakes are high, for there is very low tolerance in the marketplace for firms that experiment with new ideas that fail. The individual entrepreneur is expected to fail, whereas the corporation is expected to be stable and to grow steadily to the next level, and the next level, and so on.

To be fair, leaders do grasp that some amount of change is inevitable; they recognise that the competitive environment changes as market needs change, technologies change, and cultural and societal values change. But I emphasise: sticking to a perceived sustained competitive resource-based advantage can lead to only one conclusion – failure, brought about by the inability to adapt effectively. To achieve longevity and adapt to changing environments, business firms need to embrace entrepreneurial thinking, an entrepreneurial culture, and strategic entrepreneurship.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Strategic entrepreneurship represents a balanced approach of strategic management and corporate entrepreneurship. This combination can be viewed as a contradiction, or a paradox, given that strategic management is about stability and stick-to-it-ness, while entrepreneurship is more closely linked to risk-taking, change, and novelty. For sixty-plus years, business schools and managers have focused on strategic management as the one and only framework for enhanced corporate performance, while corporate entrepreneurship has been viewed as on the fringe and in direct contradiction to strategic management – you pursue one or the other, with strategic management being by far the dominant model.

The truth is that somewhere deep in the back of his or her mind, every executive dreams about just sitting back and enjoying the sustained operations of an organisation that, without intervention, punches out growing sustainable wealth. The evidence, though, suggests that a firm can thrive only if it supplements strategic management with entrepreneurial action that allows it to adapt to changes in the environment and seek out new opportunities to prosper as technologies change, customer needs evolve, and competitive forces escalate. The starting point for entrepreneurial actions – entrepreneurial thinking.

Dual Core Processing (Human Style)

The thinking models available through academic research are wide and diverse, but for the purposes of our study, I want to focus on the distinctions between critical thinking and entrepreneurial thinking. Critical thinking, the most common heuristic for business decision-making, relies on (1) problem identification, (2) exploring available alternatives, and (3) choosing the best alternative based on the data available. This is a shorthand version, which will suffice for now.

Critical thinking is taught because it has a huge advantage over opinion-based decision-making. By and large, children grow up in frustration and envy as parents and other adults of authority (teachers, etc.) get what they want, and the reasons why they will hear “no” in response to their actions are not always clear. This is often translated into a world view where adults get what they want because they are in authority. Reasoning becomes translated as opinion. Let me give you an example.

I run a first-year introductory session to prepare students for business school education, and ask them, “Given these three choices of posters, which should the marketing manager choose?” By nature, most students opt for the emotional answer, which will be based on their favorite colour, most pleasant mix of open space and content, attraction to certain people in the images, and so on. By contrast, critical thinking requires the respondent to step back and first ask questions, such as, What is the problem? Who are we trying to attract? What are we trying to sell? Who are our customers? And so on. Critical thinking is an extremely important skill for business students and business people to learn, but is it enough for employees, supervisors, managers, and leaders of today’s or tomorrow’s corporations?

For context, I will introduce analytical thinking to reflect analysis that occurs on a daily basis in organisations. Consider the challenge of addressing the practical problem of shrinking product margins in the face of rising costs (inflation). Analytical thinking presents the data in a specific design, defining the margins in as much detail as is called for; this includes sensitivity analysis on the impact of volume, exchange rates, sales programs, and so on. Analytical thinking focuses on one set of conditions and is useful for providing decision-making support in terms of ratios, trends, relevance, and the like. Analytical thinking helps a manager determine the optimal volume, product features, sales programs, distribution channels, and so on for a specific product.

Critical thinking is in many ways an extension of analytical thinking. Many strategic decisions are based on critical thinking, which uses the analysis available for the product facing margin pressure but incorporates other important alternatives besides. Do we outsource production? Do we retool our plant and offer a different product altogether? If we sold our plant and laid off our sales team, where would we best redeploy our capital? When the ability to compare alternatives is introduced, the limiting factor is less the data available than how the problem is framed. The question could be about the most efficient way to produce the product. Or, what is the most effective means of selling? What are the correct product features? Or, the problem could be framed in a broader context – for instance, what business is our firm in? What business should the firm be in? This is overly simplistic, but analytical thinking can at times be an effective and efficient tool for “business-level” strategic decisions (“How do we compete effectively within our chosen business line?”), whereas critical thinking is imperative for “corporate-level” strategic decisions (“What business or businesses should we be in?”).

Many of the most effective professionals, managers, and leaders have developed the knowledge and experience to know when to be analytical and when to be critical. For instance, an engineer responsible for oilfield reserve estimates and production rate expectations will use the best available expertise and standards to conduct an effective and accurate analysis. A lawyer writing an opinion letter will do a thorough review of the applicable case law and provide an expert opinion that includes reliable (likely statistically validated) estimates of outcome success. These are examples of using the right thinking process for the right job. There is a time and place to explore new methods of extracting oil or resolving conflicts, and those may call for critical thinking, possibly even entrepreneurial thinking.

Integrated thinking, as described by Roger Martin,1 reflects one possible model for true strategic entrepreneurship. Integrated thinking represents the rejection of “either/or” in favour of “and” solutions and the ability to hold constant two potential paths (described by Martin as the “opposable mind,” and depicted in my research as “cognitive resilience”). In other words, it is the combining of multiple perspectives that brings balance to integrated thinking. Ultimately, effective strategic entrepreneurship requires both critical thinking (for strategic management reflection) and entrepreneurial thinking (for the corporate entrepreneurship perspective) to form integrated thinking (balance and potential synergies between strategic management and corporate entrepreneurship). In a way, this is like the dual-core microprocessor that revolutionised computers by allowing users to attend to multiple rather than either/or computing choices.

I should mention a few that readers might wonder about. Creative thinking is expansive and accepts ambiguity, along with design thinking and various derivations of each. There are clear connections among creative thinking, design thinking, integrated thinking, and entrepreneurial thinking, and indeed, Roger Martin has provided some context to relate design thinking and integrated thinking in particular.

However, in a business context, I find it most appropriate to adopt entrepreneurial thinking as there is a clear objective, which is to find entrepreneurial solutions to business situations. Creative and design thinking connects well with some but not all situations. The moderating factor is largely dispositional in terms of individual traits. In other words, when it comes to design thinking, artists instantly “get it,” but engineers, not so much. I believe that the audience that would relate to entrepreneurial thinking provides a closer match to business.

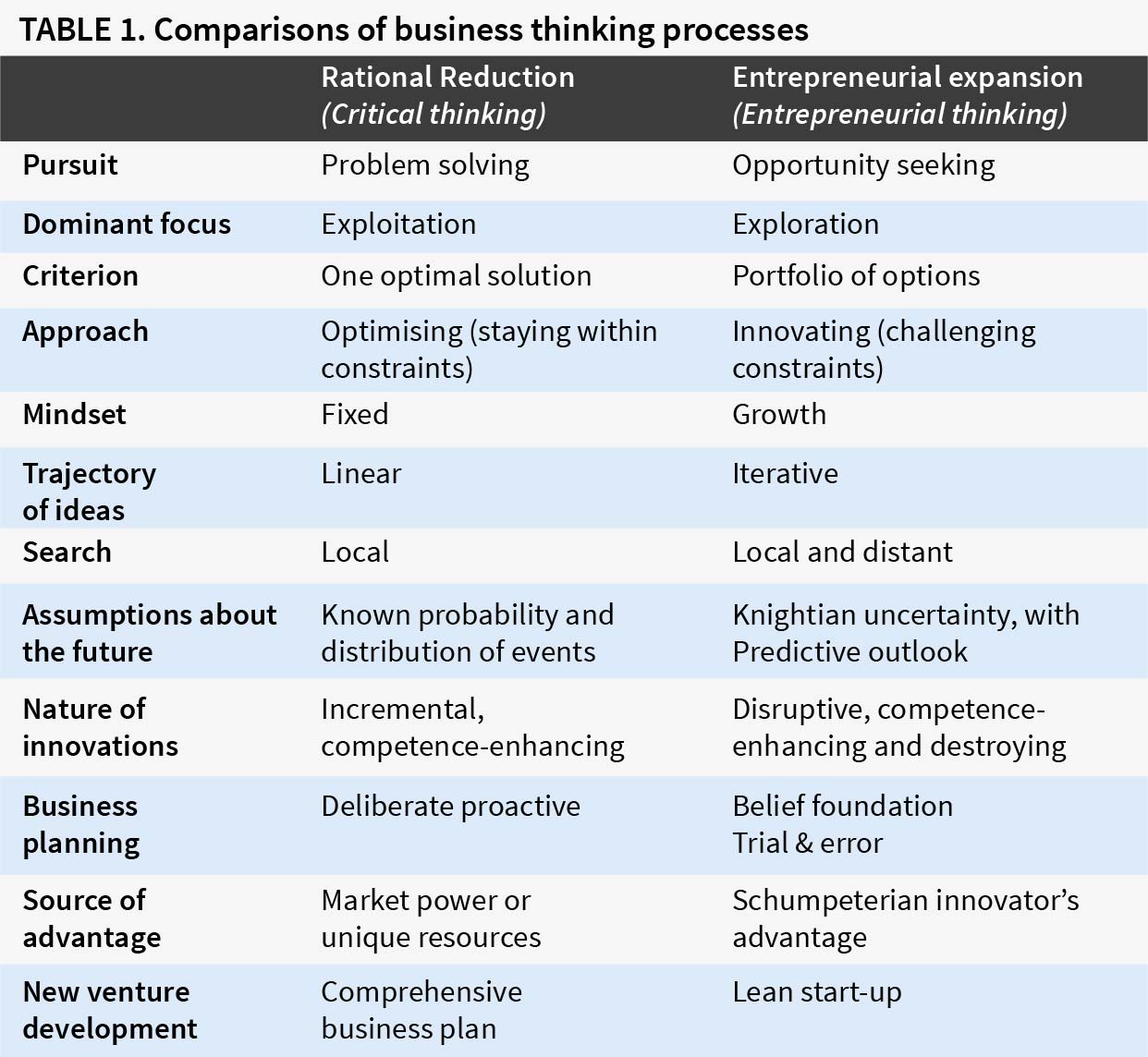

Foundational to rational reductionism is exploitation through problem solving. Critical thinking is more commonly engaged in addressing a defined problem. By contrast, entrepreneurial thinking is focused more on exploration through creating or discovering new, untapped opportunities available to the firm. In this sense, we have a divergence of thought approach right from the context-setting stage of the thinking process. (see table 1 below)

Rational reductive thinking is all about staying within the constraints but nevertheless optimising the challenge presented. This takes clever people, and I certainly would never understate the value of this approach, but it is also important to recognise that it is distinctly different from innovating, which challenges the constraints placed on a specific situation. Hence, the entrepreneurial mindset must be open to all possibilities, as well as growth-oriented as described by Carol Dweck2 in her extensive body of research on fixed and growth mindsets. Again, there is nothing wrong with a rational reductionist having a fixed mindset, provided that the model is used for the right job. Indeed, when comparing production characteristics, there is a time and place for sticking to the relevant data and not exploring new opportunities. It all depends on the definition of the problem and the job to be done.

The trajectory of ideas is necessarily linear for rational reductive thinking, and includes consideration of what the organisation has done in the past and what the industry standards are, then moving on to what is sought (whether more efficiency, or more sales, or more production, etc.). In that sense, the search is generally quite local as well, although it would not be unusual to search for geographically distant ideas. A rational reductive thought process rarely looks far beyond the home industry and the firm’s past experience for ideas. This works largely because rational reductive reasoning requires some level of comfort that the future is more or less predictable, based largely on past experience, within a reasonable margin of error.

By contrast, expansionist thinking views the future state of the world as highly uncertain, and hence the approach diverges significantly at this stage to require a more far-reaching exploration of successful approaches adopted in diverse industries, or ideas that have never been tried before. This necessitates an iterative versus linear trajectory, which can be very frustrating and unpredictable for management. Nevertheless, our research indicates that to succeed, management must be able to provide a predictive vision of how any innovation will effectively play out in this uncertain world.

Rational reductive reasoning can certainly result in innovations, but those innovations are largely incremental and competence-enhancing to support growth along the trajectory already established by the firm. Business planning is serious work, with myriad meetings, discussions, negotiations, and published documents that describe objectives, targets, and clear direction for all members of the organisation. Competitive advantage generally comes from being better at executing than the competition and hitting the sweet spots in terms of product offerings, locations, merchandising, and so on, all of which lead to measures such as brand loyalty, market share, and market power as sources of competitive advantage.

Entrepreneurial expansionism requires a search less for steady growth than for big breakthroughs by engaging disruptive innovations and technologies, some of which are competence-enhancing, and some of which are less respective of existing competencies. There is a terrible academic term used when innovations do not build on the competencies already within the firm: “competence destroying”. I say terrible because the competencies are not actually destroyed; instead, the term reflects the possibility of retraining, expansion, learning, and making use of alternative competencies. This is poor terminology that is, unfortunately, already well established in the literature.

In the entrepreneurial expansive column, business plans are prepared, but they are not as formalised and are intended more as general guideposts, not as actual plans to be followed step by step. Bankers like the business plans, but the leaders of entrepreneurial organisations are far more focused on their belief in the future and their ability to survive the trial and error process, hopefully coming out of the other end with something new and amazing.

Strategic entrepreneurship is about balancing strategic management and corporate entrepreneurship, but in practical terms, modern corporations are strategic management machines, and an understanding of the distinct differences between critical and entrepreneurial thinking is necessary to move toward a balance.

Here is my call to action – I am asking you to assess your organisation and to determine whether you have an organisational culture that will drive innovation and entrepreneurship. Do members of the organisation regularly participate in processes aimed at discovering or creating new opportunities? Are innovation and entrepreneurship consciously driven by either visionary bricolage or research-based effectuation? Do you have visionary leadership or implementation-focused leadership to thrust forward new ideas? Does your organisation take risks? How do you address resistance to change, whether from within or outside the organisation? The answers to these questions will inform you on your ability to lead your organisation to become an entrepreneurial organisation that is destined for longevity.

The article is an adaptation from the author’s book Achieving Longevity.

About the Author

Jim Dewald is the author of ACHIEVING LONGEVITY: How Great Firms Prosper Through Entrepreneurial Thinking. He is the dean of the University of Calgary’s Haskayne School of Business and an associate professor in strategy and entrepreneurship. Prior to entering the academe, he was active in the Calgary business community as the CEO of two major real estate development companies and a leading local engineering consulting practice, and president of a tech-based international real estate brokerage company.

Jim Dewald is the author of ACHIEVING LONGEVITY: How Great Firms Prosper Through Entrepreneurial Thinking. He is the dean of the University of Calgary’s Haskayne School of Business and an associate professor in strategy and entrepreneurship. Prior to entering the academe, he was active in the Calgary business community as the CEO of two major real estate development companies and a leading local engineering consulting practice, and president of a tech-based international real estate brokerage company.

References

1. See Roger Martin, The Opposable Mind: How Successful Leaders Win through Integrative Thinking (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2007).

2. C.S. Dweck, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success (New York: Ballantine, 2006).