By Pedro César Martínez Morán and Simon L. Dolan

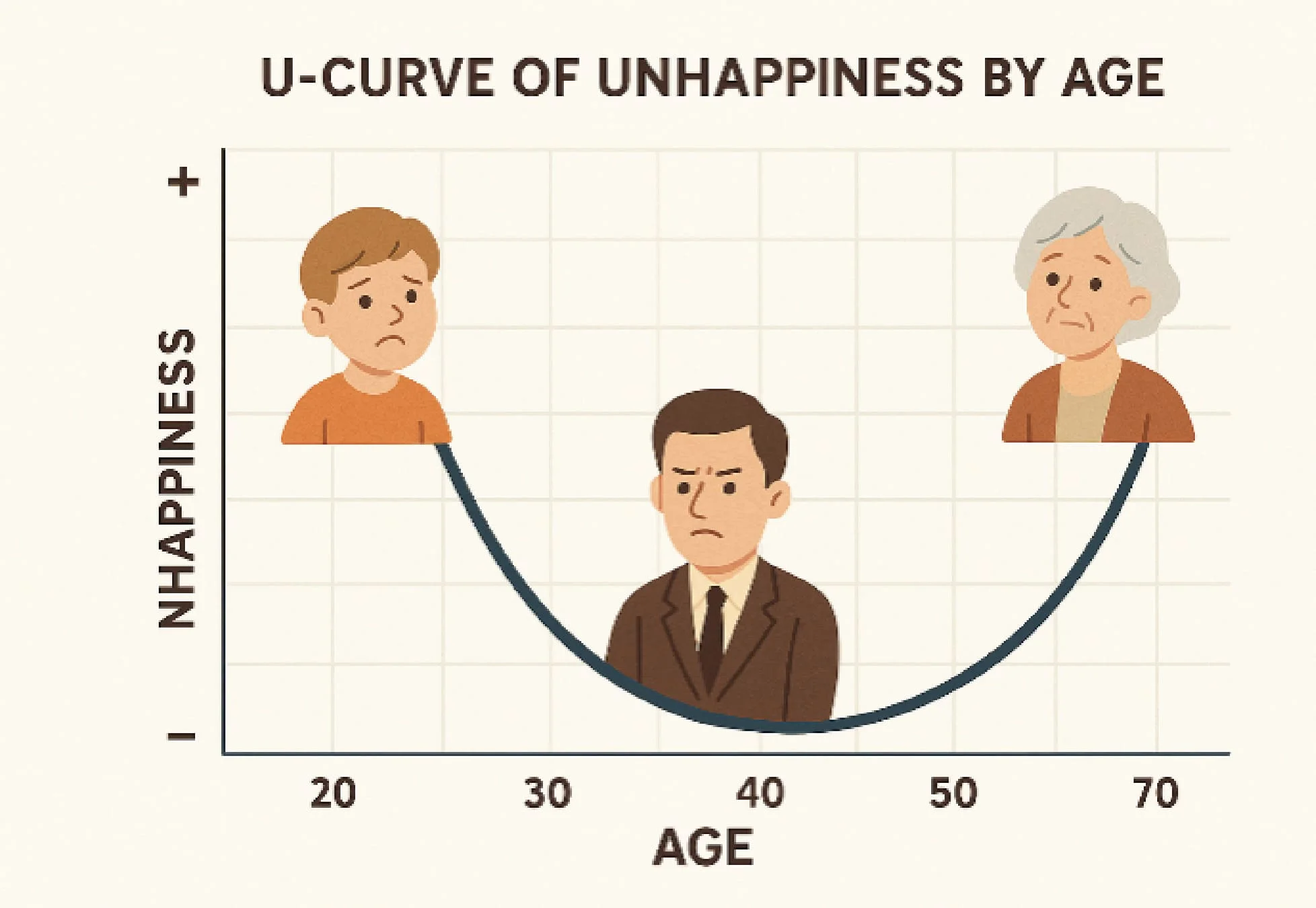

The graph of happiness against age is traditionally shown as U-shaped, with the index of happiness dipping in the middle-age years. But could the curve have surreptitiously changed shape in the age of the pernicious “S”s: smartphones, screens, and social media? And, if so, what can be done about it?

Happiness has always been the subject of analysis. What potion is hidden behind it? What are its main ingredients? There is a noble interest among human beings in understanding what it consists of and, more specifically, what factors explain this emotional state and, therefore, how it is achieved. A derived analysis from this is whether it is a final goal or if, once achieved, it can be maintained over time. It poses a challenge if it appears and disappears, or even more difficult to manage if it could be achieved, receding, returning, and so on.

There is a factor that has been used as an independent variable in the matter: age. The relationship between age and subjective well-being has sparked enormous interest in psychology and social sciences in recent decades. It seems that human beings do not experience happiness or distress uniformly throughout life. There are patterns that tend to repeat according to age and life stages; achieving it, retreating, returning, and so on.

The best-known of these patterns is the “U-shaped curve of happiness”, according to which well-being is high in youth, decreases in middle age, and rises again in old age. Its statistical counterpart is the so-called “curve of unhappiness”, which is hill-shaped, indicating that life dissatisfaction peaks around the ages of 47-49.

This classical approach has served to interpret what is popularly referred to as the “midlife crisis”, a moment when youthful expectations clash with existential reality, generating disenchantment and reconfigurations of purpose. In fact, this has led to the popularization and vulgarization of the so-called crises of the ages of 40, 50, etc.

However, recent studies have called into question the stability of this pattern. The data today points to a much more concerning phenomenon. Unhappiness no longer waits until middle age to make itself felt; rather, it appears forcefully from youth and tends to soften as one ages.

The aim of this reflection is to integrate classical findings with recent transformations, to add to the debate the role of the “happiness industry”, a framework of discourses, practices, and products that market the promise of well-being, and ultimately to highlight the important value of resilience as a valid and necessary capacity for adapting to mitigate the factors that penalize happiness.

The classic evidence: the “U” of happiness and the peak of unhappiness

For decades, various studies have shown that happiness, statistically explained, follows a U-shaped curve. This means that people tend to feel quite satisfied in their youth, approximately between the ages of 18 to 30, go through a notable decline in well-being during middle age, roughly from 35 to 55 years old, and then experience a significant recovery after the age of 55.

On the other hand, indicators of distress (stress, loneliness, depression, anxiety, sleep problems) have shown a peak-shaped pattern around 47-49 years of age. This critical point is linked to the time in life when family, work, and social pressures become more intense, such as having teenage children, caring for older family members, established but not always satisfying professional careers, and confronting unfulfilled dreams.

Nevertheless, scientific literature emphasizes that this peak of unhappiness is transitory. Most people, after going through middle age, recover their levels of satisfaction. In old age, external pressures usually decrease, the ability to appreciate what has already been achieved increases, and a sense of vital serenity solidifies.

Recent transformations: the collapse of the hump of unhappiness

However, the outlook has begun to change dramatically. A recent study labelled “The declining mental health of the young and the global disappearance of the unhappiness hump shape in age” shows that the famous midlife unhappiness hump has practically disappeared. The new pattern is based on the fact that levels of unhappiness are already very high among the youth and, instead of worsening in middle age, well-being tends to even improve with the years, and older generations today report greater well-being than the young.

The main hypothesis that would explain this shift points to an accelerated deterioration of youth mental health in the last two decades. Among the most cited causes are persistent economic crises, such as the Great Recession of 2008, which left deep scars on young people entering the labor market with few opportunities and prospects; a deficit in access to mental health services (overloaded public systems, delays in diagnoses, and lack of preventive resources); the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which intensified anxiety, feelings of uncertainty, and hopelessness; and the intensive use of smartphones and social media, whose causal relationship with youth psychological distress is increasingly documented. Continuous exposure to social com–parisons, approval dynamics, and unrealistic content fuels distorted expectations and feelings of inadequacy that affect self-esteem.

The result is that today it is the young people who are the unhappiest, contradicting Rubén Darío and his famous “youth, divine treasure, you are already leaving and will not return”.2

Nuances and debates surrounding the curve

Although the evidence of the U-shaped curve of happiness has been solid in statistical terms, it is not universal. Its form varies according to income and economic contexts, gender and experiences of discrimination, physical health, and cultural expectations.

Some cohorts even show sustained increases in happiness from youth to middle age. Neurobiology supports these differences: while young people seek pleasure and intensity, adults tend to value stress reduction, and in old age, serenity is prioritized.

In other words, the happiness curve, which in simple terms can be described as a visual representation of how happiness varies throughout our lives, suggests that it tends to be high in youth, may drop in middle age, and eventually increases again as we get older. Mind you, it is a concept that has sparked a lot of debates and nuances, and that’s great because it gives us the opportunity to better understand what we feel and how we live.

As individuals mature, they develop a greater appreciation for what truly matters: meaningful relationships, rewarding experiences, and a sense of purpose.

First, it is important to recognize that this curve is not a universal rule. Some people may find that their happiness increases as they move past adolescence and enter adulthood. Others, however, may experience challenges that affect their well-being at different times in their lives. This is where nuances come in; our experiences, personalities, and environments greatly influence how we feel happiness.

Additionally, another interesting debate revolves around the nature of happiness itself. Is it simply an emotional state or is there a deeper component related to life satisfaction? Some research suggests that, as individuals mature, they develop a greater appreciation for what truly matters: meaningful relationships, rewarding experiences, and a sense of purpose. This approach can make people feel happier, even if life circumstances are not ideal.3

In fact, empowering ourselves with this perspective encourages us to seek happiness in places that we might have overlooked before. And that’s really exciting! Each of us has the power to find or create those moments of joy, even in phases of life that are traditionally considered difficult.

And let’s not forget the importance of community. Social interactions and support from friends and family are crucial. In this sense, the happiness curve gives us an opportunity to reaffirm the need to be connected. While our paths may differ, the act of sharing our experiences and emotions can be incredibly valuable and transformative.

In conclusion, the nuances and debates surrounding the happiness curve show us that happiness is not a straight line. It is a journey full of twists and nuances, in which each of us contributes their own experience. So, celebrate your moments of happiness, and remember that, no matter where you are on that curve, there is always room to grow and find joy. We are in this together, so let’s keep exploring what makes us happy!

Positive psychology and the PERMA model: from deficit to the construction of well-being

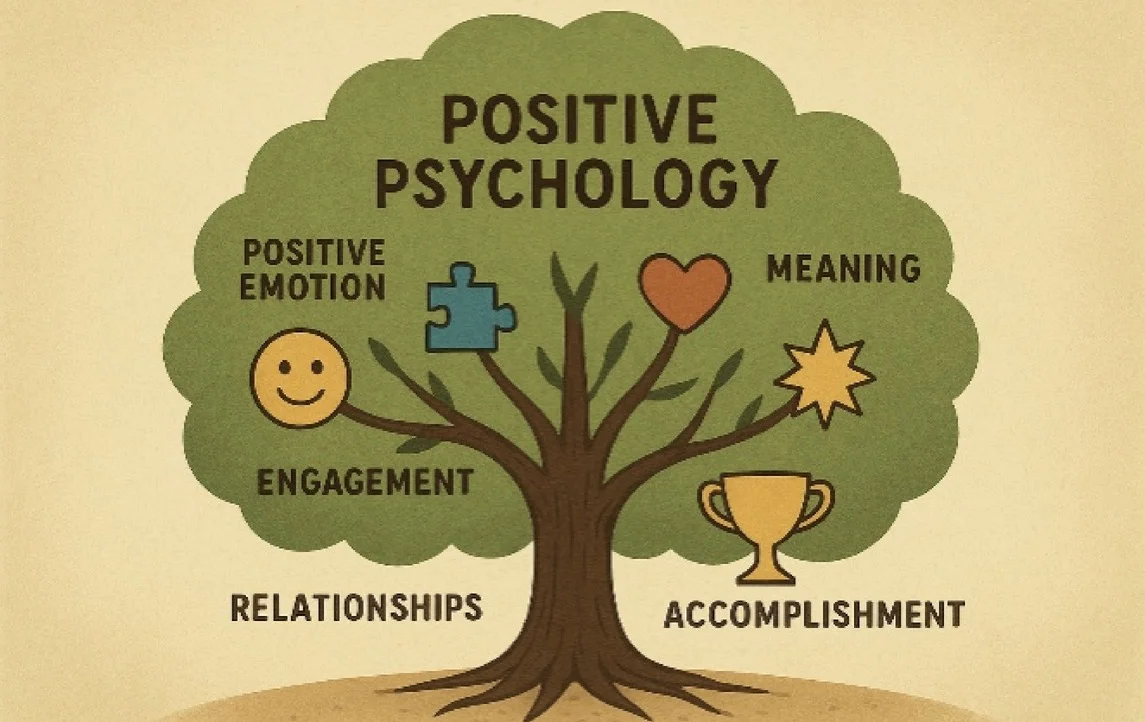

Positive psychology proposes a fundamental shift. It is about not analyzing well-being only from the absence of distress, but from the conscious construction of conditions that promote it. Martin Seligman, one of the key figures, synthesizes well-being in the PERMA model.4 In very brief terms, it means this:

- P (Positive Emotions): cultivating positive emotions such as gratitude, hope, and joy.

- E (Engagement): to experience states of “flow” or full immersion in meaningful activities.

- R (Relationships): maintaining strong relationships of trust, support, and affection.

- M (Meaning): finding vital meaning and feeling part of something greater than oneself.

- A (Accomplishment): pursuing goals and developing achievements that generate pride, meaningfulness, and satisfaction.

This approach seeks to counteract the growing unhappiness in youth with practical tools of gratitude, mindfulness, purposeful activities, and quality social connections, circumstances that would lead to a fulfilling life.

Waldinger and the science of relationships

Robert Waldinger, director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, provides a finding that spans generations: the best predictor of long-term well-being and health is not economic achievements or extraordinary travels, but the quality of everyday relationships.

After more than eight decades of following hundreds of people, Waldinger and Schultz conclude that those who had solid relationships, capable of sustaining empathy, gratitude, and conflict resolution, aged with better physical and emotional health, and reported higher levels of life satisfaction.5

The happiness industry: promises, contradictions, and risks

The so-called “happiness industry” encompasses everything from mindfulness applications, motivational coaching courses, self-help literature, and alternative therapies to large corporations that promote “corporate wellness” programs. It is a multibillion-dollar market that turns the quest for meaning and happiness into a consumer product.6

This industry is based on three pieces of logic: the individualization of discomfort, through which the idea is conveyed that unhappiness is always a personal responsibility, making invisible structural social determinants such as inequality, job precariousness, urban loneliness, or vital insecurity; the standardization of happiness, which is disseminated as a normative model of well-being, associated with always being productive and positive, ultimately generating additional pressure and feelings of failure for those who do not conform to these frameworks; and finally, consumption as a solution, because it reinforces the notion that happiness can be acquired by purchasing a course, an app, a spiritual retreat, or even a material object that promises to transform one’s life.

Resilience: the silent strength of well-being

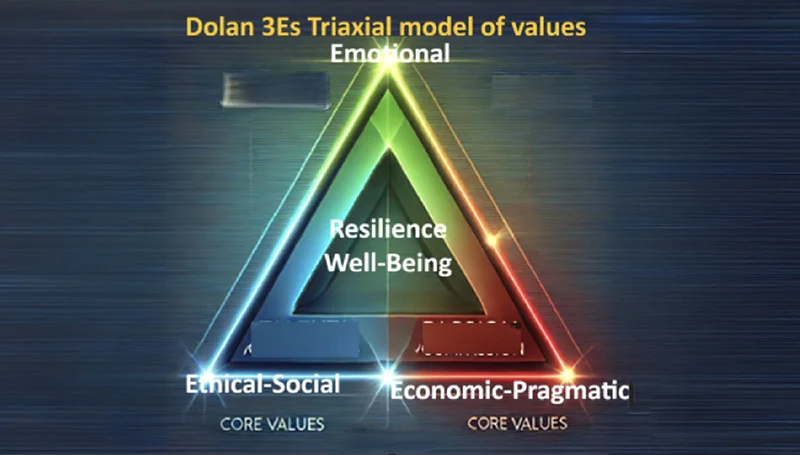

Resilience is understood as the ability to adapt positively to adversity, learn from difficult experiences, and emerge strengthened. Within the framework of Simon Dolan’s contributions, this concept takes on a central role in the construction of sustained emotional well-being.7

Dolan argues that the balance between the three major axes of values—Economic-pragmatic, Ethical-social, and Emotional-developmental—is key to generating well-being both individually and organizationally. In this sense, resilience acts as a moderating factor that helps maintain that balance in the face of pressure, uncertainty, or crises.8

When a resilient person goes through a difficulty:

- They reinterpret the experience from a framework of meaningful values (connection with meaning and purpose).

- They mobilize emotional resources (optimism, self-confidence, emotional regulation) that cushion the impact of stress.

- They strengthen social relationships, a key aspect that Dolan identifies as essential for emotional health and team cohesion.

- They learn and transform adversity into opportunity, aligning achievements (pragmatic values) with personal growth (emotional values) and ethical commitment to others.

In this way, resilience not only protects well-being but also expands the possibilities for emotional flourishing. Following Dolan’s line of thought, it becomes a practical value that enhances the capacity for positive leadership, change management, and the building of more humane organizational cultures.

Conclusion

The change in the unhappiness curve has profound consequences. In public policies, it is urgent to invest in accessible, preventive, and inclusive mental health, especially aimed at the youth. In education, resilience programs, emotional literacy, and a sense of purpose are needed from school stages. In everyday life, it is important to take a critical distance from the happiness industry, prioritize meaningful relationships, encourage spaces for digital rest, and cultivate practices of gratitude and authentic purpose.

The traditional U-shaped curve of happiness and the peak of unhappiness represented an optimistic narrative for years. Although one would go through a valley of disenchantment in middle age, recovery would come sooner or later. But contemporary reality breaks that logic; distress hits younger people harder, while well-being seems to increase with the passage of years.

This change poses a challenge for society, such as ensuring that new generations have the emotional, social, and economic resources they need to navigate life meaningfully. In the face of the temptation to rely solely on quick fixes from the happiness industry, it is crucial to reclaim a holistic vision of well-being through a daily practice of connection, gratitude, purpose, and collective care.

Happiness, more than a destination promised by emotional marketing, is a cultivable process that is built in the fabric of relationships, in the acceptance of ordinary life, and in the pursuit of shared meaning.