By Kristine M. Kawamura, Mario Raich, Simon L. Dolan, Dave Ulrich and Claudio Cisullo

Our desire to design a better future for those coming behind must be guided by a new framework that considers the complexity of a yet unknown future and the different forces that influence it.

Throughout human history, people wake up to the fact that we are here for only a short “blip” in time. They may look up to a starry night and ponder the vastness of space, the greatness and smallness of their own lives. This sudden awakening to the preciousness of time inspires many to contemplate the meaning and purpose of their lives; their placement in history; their role in creating or at least influencing the future; or the power of their own choices to change direction, influence others, and contribute to the greater sense of meaning in the course of human history. It leads many to recognise that each one of us is a valuable yet momentary hero or heroine, living our life in a human society on a living, breathing, and changing planet.

Scientists and philosophers, too, explore the meaning of life within their respective disciplines and perspectives. We know from quantum mechanics, for example, that all material objects simultaneously exist as a wave and a particle. This paradoxical mystery also applies to the experience of being human beings. On one hand, we flow (sometimes bumping along) through the journey of our lives — growing, learning, changing, and eventually, moving into the great unknown. Simultaneously, at any one moment, time stands still and the greater context of our society and world is frozen in meaning and experience. We live each moment embedded in a specific society that is surrounded by a dominating “Zeitgeist” (a term often described as the spirit of the age, the overarching mood of that specific period that is constantly being created, and recreated, by the overarching ideas, beliefs, and events of that time.)

Life, itself, comprises waves and particles, experiences that are both individual and shared. Our moments in life are the particles; our journey through life, the wave. With life so short in the arc of the universe, our proposal is that one’s life should focus on goodness—being our better selves, contributing our strengths and values to create a better world, and taking action to design a healthy, thriving, and “best” future. Given the power that human beings have to envision the future, act, and produce impact, we see the value and responsibility for people of all cultures, disciplines, and walks of life to create meaningfulness, happiness, and even bliss for ourselves and others with whom we walk our journey through life’s moments.

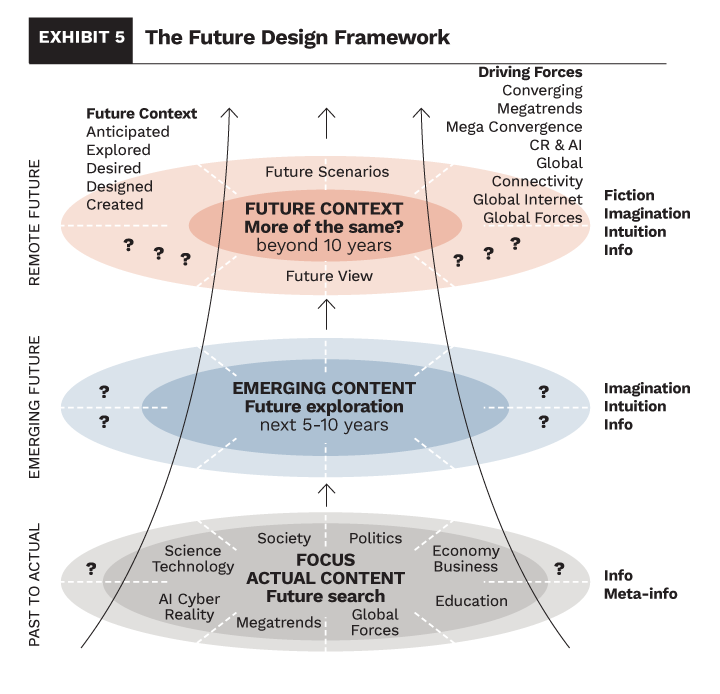

This is the first of a two-part article. In part I, we discuss why we need a new framework to guide our efforts to design the future. We describe the Future Design Framework (developed by futurist Mario Raich, coauthor of this paper), and its foundational concepts. The issues discussed hereafter become of utmost relevance, especially in view of the recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI), for which some fear that it can possibly destroy humanity (see: Delbert, 2022).1

The Need for a Future Design Framework

Given that we don’t know the future, seeking to design the future is simultaneously stimulating, presumptuous, and terrifying. We can’t see it, touch it, or fully anticipate its possibilities and risks. Human beings live within an external, environmental context of forces, paradigms, assumptions, and axioms. We also operate from an internal, inner context that has been shaped over time. In this paper, we describe the positive and negative interpretations of the disruptive forces we face today and propose longer-term possibilities that may arise from these forces. We then present a model that portrays the complex, inner life of human beings and suggest methods to harness the potential capabilities that people may bring to the future design process. We propose that understanding our outer and inner contexts is a necessary process for future design and for creating meaningfulness in our work and lives.

Environmental Forces for Change

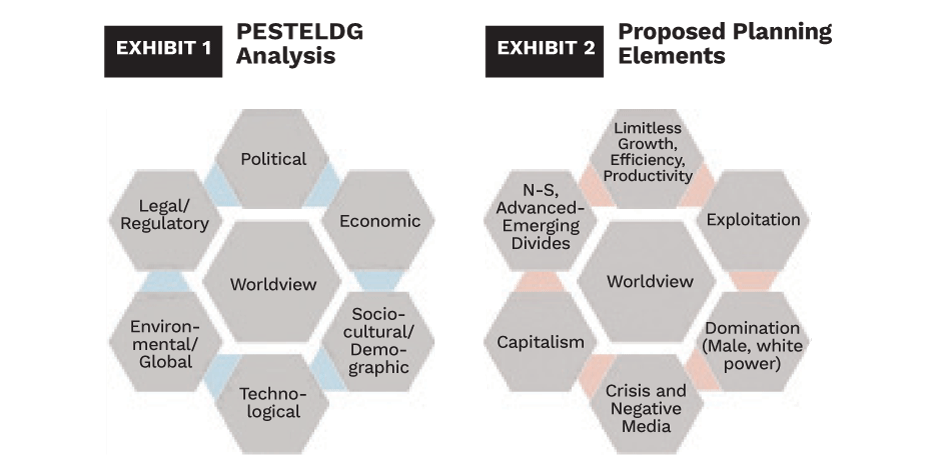

Most business professionals, strategists, and innovators are familiar with the process of analysing environmental forces through the lens of PESTELDG, a nomenclature that stands for, political, economic, sociocultural, technological, environmental, legal/regulatory, demographic, and global forces. All of these numerous interconnected forces characterise the present reality, which together formulate the current worldview we hold both as we perceive today and the future.

The Other Forces for Change

Technology and Economics as a Force for Change

Several interrelated elements of a PESTELDG analysis attract our attention. First is the advent of the Cyber-Age, which has moved us into a world in which digital systems—operating on their own, interacting with more conventional physical systems, human beings, and the environment—have flattened, quickened, and connected our world. This era is ripe with the potential transformation of business, education, culture, and society. Given the potential of the fourth industrial revolution to revolutionise the speed and scope of the creation and destruction processes, it mandates new regulations and changes in political systems and the role of government. Second is the convergence of advanced technologies—especially virtual reality (VR), alternative reality (AR), and AI—with their potential to alter our life and work, far beyond anything we can envisoin or expect. Advanced technologies also present new avenues for value-creation and new ways of working, living, and building relationships. There are also inherent risks and threats. Leaders and organizations may be unable to gather the full range of benefits or mitigate against the extensive spillover costs associated with advanced technologies. When technology is used to exacerbate polarisation, drive apart societies, and incent racism, terrorism, and war, it simultaneously increases anxiety and fear about the future threatens the destruction of the very fabric of society we honour and value.

Most powerfully and dramatically, the Cyber-Age facilitates the possibility to change the paradigm of the economy and economics and bring back meaningfulness into politics and the political-socio-cultural-economic systems that gird our world. For at its core, the central question of economics is to determine the most logical and effective use of resources to meet private and social goals by providing products and services that are valuable and meaningful, to individuals, communities, and societies. Our overwhelming drive for profit as a core element of capitalism, however, has motivated many leaders and organisations to exploit the planet and resources, creating spillover costs and negative collateral impacts on society and the environment. (For example, we accept the harmful and damaging impact of CO2 on the environment. We cannot even manage to gain agreement from the multiple stakeholders, in most industries and corporations around the globe, to work towards CO2 neutrality or to reduce their CO2 levels, much less acknowledge that we have a climate change problem!)

The pervasive focus on profits has created profound distortions in the meaning of economy. Economics is really “economy in action.” The purpose of economics (along with the application of resources and innovation processes) is to provide meaningful products and services for individuals and society, meaningful value creation, meaningful work, and the sharing of created value (through work, education, and economic development activities). Work, in fact, gives meaningfulness to our lives and the opportunity to create relationships—what research has shown to be the most important basis for a healthy and happy life.2

The Western Zeitgeist as a Force for Change

The Western Zeitgeist (“spirit of the ages”) has been pervasive in nearly all our systems and primarily, the movement to capitalism.

The capitalism mindset has been forged from

many forces:

- Hundreds of years of limitless growth and exploitation of resources have stressed the planet and people, exacerbating a toxic relationship with productivity and performance and widening inequities and inequalities in our systems.

Societies of domination (white power) along with the subjugation of people of colour, native communities and cultures, and women. The control of human beings through slavery, marriage, and lack of opportunity has led to inequity and inequality across the globe. - The fake news in the social media that spreads like fire, with politicians taking advantage of the tools and content to manipulate us. All this carries the promises of a different future. But it is up to us whether it will increase the quality of life or become a threat to humanity.

- The focus of the media on bad news, constantly fueling our worries and fears, as we see crises everywhere: financial crisis, political crisis, social crisis, etc. Whether real or perceived, existing or not, crises and threats are increasing our anxiety about living.

- The lack of trust in traditional institutions such as corporations, governments, and religions has left people feeling cheated and betrayed by their leaders.

- The poor decisions made by parents and adults have burdened young people with a pillaged planet and the responsibility to “fix it.” These paradigms have powerfully skewed our perceptions (and thus our decision-making) for hundreds of years. Thus, our current reality as well as the one we project into the future is based on biases and judgements cemented not only in our own minds but also in our communities, organisations, societies, and institutions.

The Inner Context as a Force for Change

As human beings, we need to develop the capacity to overcome our limitations to perceive the reality around us as well as transform the layered perceptions we hold that have been “hijacked” by cultural and personal biases. This will empower us to reimagine, redesign, and reinvent our systems and paradigms in our quest to design our “best” future.

We believe there are three patterns that need transformation:

- Our tendency to view the world from the lens of our reality; what we see mirrors our stored memories, experiences, and perceptions influenced by the dominating worldview (Zeitgeist), biases, and even prejudices—all of which are stored within brains and nervous systems. These affect what we consider as possible and impossible, acceptable and unacceptable as well as our likes and dislikes and mental comfort zone.

- Our human habit to project our past experiences and present status into the future.

- Our propensity to project our own experiences, views, and preferences onto others, expecting them to feel, think, and behave similarly to ourselves.

How do we address these patterns and develop the capacity to view and hold the future with empathy? By adopting a hope-filled, growth mindset, making a courageous commitment to learn and grow, and undertaking the inner work to free oneself from these entrenched patterns3. There are many paths to this journey, depending on the individual. One may study human and social history; choose to travel, study, and/or work locally, regionally, and globally. One may develop relationships with people from a wide variety of backgrounds, mindsets, and cultures—appreciating both similarities and differences. One may also seek to develop a range of intelligence sources, expanding their own capacity to learn, connect with others, and collaborate.

An Important Note: Design Thinking Isn’t Enough

Although design thinking may be incorporated when designing the future, it may not be sufficient to address the complexity of thought process, creativity work, and transformation needed to achieve such a complex goal. In a few words, design thinking is a problem-solving process that focuses on solving the needs of a specific group of people, which is usually an organization’s customers.4 The approach matches customer needs with what is technologically possible and converts this into a business strategy that offers value and market opportunity. Design thinking can be used by all types of businesses as no one can ignore the changing needs and desires of their clients. Citing Grubel: “Design thinking draws upon logic, imagination, creativity, intuition and reasoning to explore the possibilities of what we could create to enable the desired outcomes for our end users.”5 The process involves five steps: 1) developing empathy for the end user; 2) identifying the problem; 3) using ideation techniques to create scenarios and solutions; 4) prototyping solutions; and 5) testing solutions with groups of consumers, users, and other stakeholders.

However, we see three critical weaknesses in attempting to design the future with this methodology:

Perception and bias: The team will implement all the steps using the current perceptions and biases of its members (and of the team itself). People’s brains and nervous systems are wired to recognise familiar patterns based on historical experiences and stored biases. The ability to empathise with the future will be based on the current reference frame and perceptions of the future.

Change and time: The design thinking process cannot address the fact that all inputs, outputs, and the process itself will evolve through the time and space involved in moving into the future.

Selection and information bias: The group will also be affected by selection bias and information bias. The members selected to be part of the group will most probably not match the characteristics of future members (who will have evolved given the environmental disruptions we will be facing, such as the human-AI-robot interface). Information bias will most probably occur because key study variables, ideas, and prototypes that will be possible in the future will not be known today—again affected by the lack of ability to perceive the future with “new eyes.” Because of defining shared values as part of the design process, it will be difficult to “lift” above the group’s individual values and perceptions of the problem, solutions, and future possibilities.

We believe a new framework is needed for desgining the future.

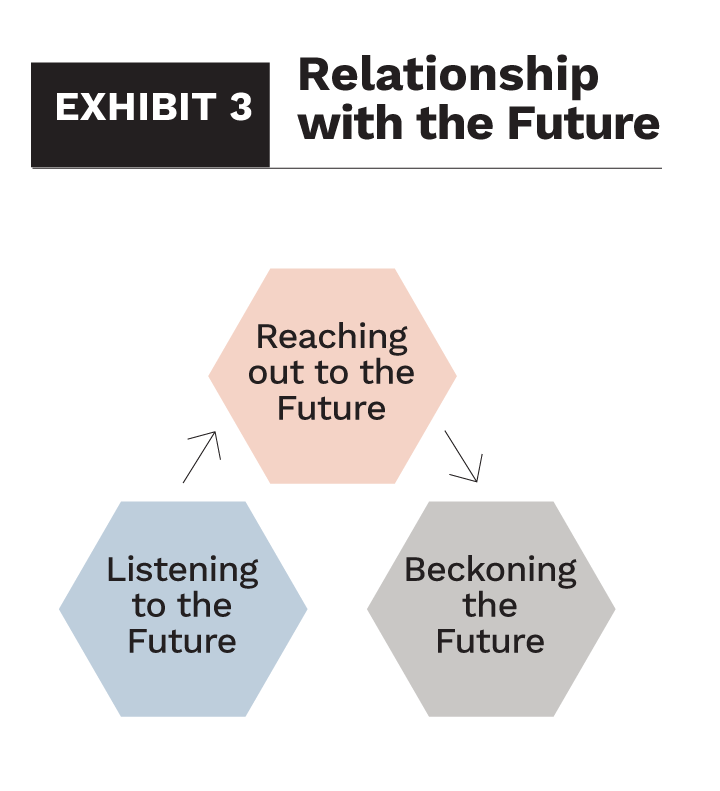

An Overview of the Framework for Future Design

The Future Design Frame-work has been developed to build a relationship with the future in three different ways. 1) To reach out to the future from our current reality; 2) To beckon, or call forth, the future to enter the creative void; and then, 3) To listen to the future when it appears in the design process. (See Exhibit 3)

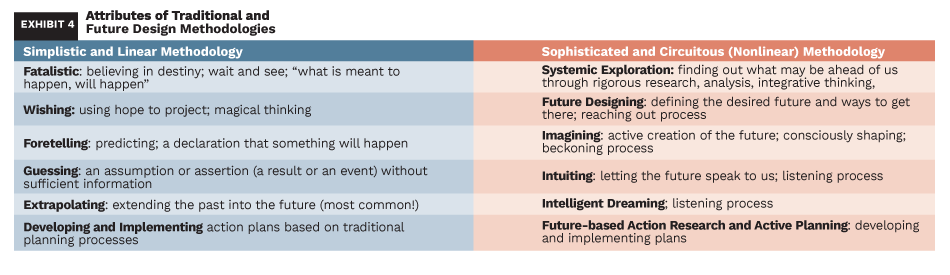

Unlike a traditional lineary framework, the future design framework is a sophisticated and circuitous (nonlinear) methodology that can be used to systematically explore, define, and create the future. It supports designers to utilise skills of imagining, intuiting, and intelligent dreaming along with action research and active planning to dynamically integrate both the direction and action over time and space.

The Future Design Methodology simultaneously comprises three modalities of time and space: the actual (and immediate context), the emerging future, and the more remote future—all three of which are juxtaposed within a world in great transition and a future that is in permanent and dynamic transformation. (See Exhibit 5). The framework thus provides a process that a) focuses on the desired future rather than the (currently) expected one; and b) views the emerging and future stages as dynamic rather than static. Because the framework works multi-dimensionally as well as cyclically, it allows us to cope with an ever-changing future as well as to take meaningful action along the way. In short, the framework allows us to develop a “future design,” which leads to the creation of both, or either, an emerging future view and a remote future view.

The Future Design Methodology simultaneously comprises three modalities of time and space: the actual (and immediate context), the emerging future, and the more remote future—all three of which are juxtaposed within a world in great transition and a future that is in permanent and dynamic transformation. (See Exhibit 5). The framework thus provides a process that a) focuses on the desired future rather than the (currently) expected one; and b) views the emerging and future stages as dynamic rather than static. Because the framework works multi-dimensionally as well as cyclically, it allows us to cope with an ever-changing future as well as to take meaningful action along the way. In short, the framework allows us to develop a “future design,” which leads to the creation of both, or either, an emerging future view and a remote future view.

Concept Foundation-I: Management by Traction Framework

At the core of the Future Design Framework is the Managing by Traction (hereafter MbT) Framework.6 MbT is a simple and effective way to move forward in a dynamic form towards the selected direction. It acts as a simple feedback loop, building a dynamic and interactive relationship between “direction” and “action.” MbT incorporates five interdependent elements: 1) the context (an understanding of the world in transition i.e., driving forces, enablers and megatrends); 2) the MbT transformation framework (including three mutual feedback loops between direction and action: the actual, the emerging, and the future); 3) the direction (the guiding star towards which we are pointing); 4) the action (the nonlinear steps taken in quest of the direction within the changing context); and 5) the methodology utilised to discover and “find” creative solutions.

The application of action and direction in a design process, by themselves, are not new concepts. What is new, however, is defining and utilizing them in light of our turbulent environment; constantly changing players over time and space; the dynamic regeneration of three mutual feedback loops that are simultaneously changing and interdependent; and, the application of a “pull” strategy, in which the design process is pulling information and inputs from a future that does not yet exist.

It is important to understand the relationship between direction and action in MbT. With this process, the direction becomes an active part of the action, which can, in turn, continually influence and shape the identified direction. Direction and action, therefore, operate in tandem, with direction showing the way for the action, and action shaping the direction based on the outcomes implied in the direction.

Once the direction is established, the actions take the lead. The process continues as an interaction between the direction and action with three mutual feedback loops concurrently running (the actual, the emerging future, and the future). Continual assessment of the alignment between action and direction is required, in case corrections are needed.

Concept Foundation-II: Seeking the Middle Way between Dystopia and Utopia

What is critical in the journey is that we begin by embracing “flaws,” differences, and points of conflict within the design process and team. As we imagine collaborative groups of people partnering with others from different communities and societies working in the design process, we know that we will see a wide variety of degrees of ideas and progress. Such work in the creative void is necessary to the innovation process. The all-encompassing partnership process is based on many principles, including mutual respect, trust, common ground, open communication, complementarity, honesty, acceptance of the unknown, and willingness to walk through a transformation (and grieving) process.

These principles will be necessary to guide partnerships to navigate the journey through two overarching emotional and creative-destructive forces:

- Dystopia: the imagined state or society in

which there is great suffering or injustice; typically, one that is totalitarian, post-apocalyptic; the after-effect of environmental disaster, with characteristics such as controlling, oppressive government, anarchy or no government, extreme poverty, and banning of independent thought; - Utopia: the imagined place or state of things in which everything is “perfect;” with characteristics of peaceful governance, equality for all citizens, a safe and healthy environment, and education, healthcare, and employment for all.

As we experience today’s disruptive forces, dystopia seems to prevail as we experience fear and anxiety (that is exponentially spread through social media). Utopia, on the other hand, seems more like a wishful dream we hold for the future of society. The utopian-dystopian dilemma creates a vacuum between the two opposing forces. We are pulled between competing values such as love and hate, greed and generosity, good and evil, individual and community, survival and transcendence, and differentiation and collective beingness. Within the void lies potentiality, imagination, and creativity—all sources of power to mitigate the lack of committed action some people call fate.

For future design, we seek to travel the middle way between dystopia and utopia. The middle way forms its roots in Buddhist thought, which describes the middle ground between attachment and aversion, between being and non-being, between form and emptiness, and between free will and determinism. The concept can be applied to any dualism or diametrically opposed pair; in between any two opposites lies emptiness.7 This creative potential is needed to develop and implement solutions that will allow us to preserve and enhance life quality and solve global issues that threaten the future of humanity. Creative energy plus transformational innovation inspiring entrepreneurship can help us shape our world for better or worse—a direction that depends on our guiding purpose.

How can we motivate others to follow the middle way? Though Max Weber said that the sword, money, and words are tools to motivate people, we believe that more powerful inspirations are imagination, dreams, and love. The future begins with the ideas in our heads, the purpose in our hearts, the tools in our hands, the values we share, and the dreams and imaginings of the human spirit.

Concept Foundation-III: Context Matters

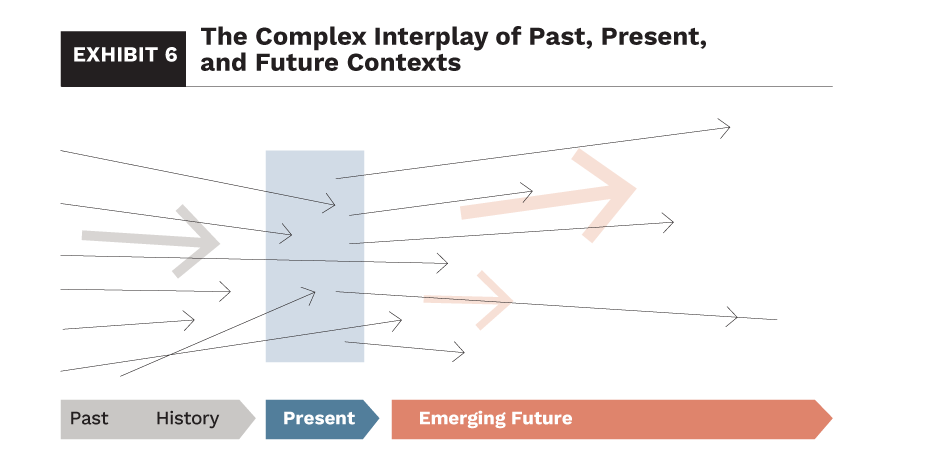

The future design process will be crafted from the complex interplay of past, present, and future contexts (See Exhibit 6). After all, the present moment is not a lone experience. As we stand in the present moment, we are rooted in a greater environmental context that has been built from past experiences, paradigms, and concepts. As we view the future from the present moment, it is a projected one, necessarily affected by the past and the present. Juxtaposed between the time and space of the past and future, the present moment is merely an arbitrary halt within the currents of time, ripples in space, and heartbeats we ride, the moment from which we dynamically project the future.

The context with which we perceive anything is always relevant. It is dense, complex, palpable, ever-changing and ever-being created. It can be continuously reimagined.

To easily understand the impact of context, think about your own life! You are an individual who can be differentiated by many attributes as well as skills, work and life experiences, talents, and interests. You have also been influenced ever since you were born by multiple systems, paradigms, and axioms: the political, economic, and social systems of your country; your cultural roots and values; your family’s priorities, rituals, and values; the rules defining good behaviour, rewards, and punishments that are defined by your family and society; and the assumptions that underlie every perception as well as process (including the meaning and application of the future design process!).

Context, too, establishes the foundation for our perceptions, including our individual mindset, worldview, and overarching Zeitgeist. Context provides the container for bias, spawns its development, and nourishes its perpetuation. Unless and until the designer is able to lift out of his or her bias, it serves as a concrete foundation in his or her nervous system. As the firmament for a society’s worldview and Zeitgeist, bias can rule and regulate the future design process.

Imagine how the designer’s perceptions and bias towards advanced technologies can impact their implementation and use in the present as well as greatly influence and control their role in the future. As we stand on the edge of the virtual frontier, many people are excited over the potential for artificial intelligence, the metaverse, virtual reality, augmented reality, and other Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies. They envision the possibilities for creating immersive experiences across sectors (technology, entertainment, education, and retail) and within business functions (product/service development, customer and employee experience), for providing interactive sensory space for human beings and whole communities in their daily tasks, for creating new and increasing sources of economic value.

On the other hand, this is scary stuff! We are challenging the separation of human beings and technology, somewhat like the separation of church and state. There are huge risks and negative potentials from lack of control as we seek to control human beings, mindsets, emotions, consumer purchasing, decisions and the like. Such fear will impact the range of potentialities born from these advanced technologies. Perhaps positively? Perhaps negatively? Time will tell.

The context set by science and philosophy is always changing as well as we can see in the changing view of the source of illness (arising from imbalance or God?), the perspective of the earth as flat or round, or the relationship between the greater cosmos and divinity.9 Designer Johannes Jörg writes that today’s cosmos tends to be free of divinity, has no centre at all, and is almost infinitely larger than anything that’s even possible to imagine.10 He also says that our ongoing understanding of ourselves will dramatically expand the boundaries of our inner cosmos, emphasising the importance of introspection (beyond the more objective avenues to knowledge such as empirical evidence and logical reasoning) to self-understanding. He writes, “It seems to me that Western culture in the beginning of the 21st century is facing a corresponding cultural situation regarding the inner cosmos. Looking inside the human intellect, one is faced with a similar, stubborn bias of perspective as we look towards the stars five centuries ago.” This evolving view challenges us to look at the biases we hold resulting from our greater contextual understanding. If change is to happen, it must start on the inside.

Whether we are talking about the past, the present, or the future, context matters. Our views of the future have developed over time, and its possibilities and risks defined in terms of our current context and perception. Even the very perception of context we hold is built on the systems, paradigms, assumptions, and axioms that have been taken to be true. A system (of thought as well as perceived reality) built this way can be logical and rational; it can be partially true or, in the worst case, totally wrong. We only have to look at the great number of false “truths” about the Covid-19 pandemic posted on the internet or perpetuated by “fake news” channels to see this lived out today.11

Summary of Framework Tenets

The Future Design Methodology rests on several tenets:

- When we are moving into the future, the unknown is only continuing to grow bigger in scope while also evolving at ever-increasing speeds. Additionally, we need to start with deeper insights into the actual context of the past, present, and future to both prepare for our journey and extend our understanding of the future.

- Arising from advanced technologies, increased complexity in managing and governing organisations, and structures, processes, tools, and instruments become increasingly incapable of adequate application, we are living in a state of permanent transition. Context (along with contextual changes) is becoming a driving force of transformation. This will most likely lead to growing disruption and transformation in all key aspects of human life: society, economy, business, science, technology, education and politics.12

- The future design process challenges us to move beyond our traditional strategic planning processes, intuition patterns, and sources of wisdom. It is designed to “push” (and “invite”) people and organisations to work beyond their comfort zone and reframe intuition patterns—a valuable capability in times of permanent change.

- The Future Design Framework supports these needs by taking a complex and systemic view, employing visual models so that insights are more intelligent and communicable, and is developed for collaborative work.

- The end users—and other beneficiaries of the design process—are the many diverse communities and societies that span our globe as well as their individual members who are all seeking to live lives of meaning while walking through transformations we can’t fully see or understand.

Our ideation process must build evolution, transformation, and movement into its core and allow for the constant exploration of an ever-changing context (including both the environmental/outer context and the personal/inner context). - Prototypes must include possibilities yet not envisioned, provide meaningful and equitable impact, and integrate with advanced technologies that are continuing to evolve from today to tomorrow. Testing must occur at multiple levels—human, robotic, and AI as well as individual, relational, community, spatial, and all the interconnections between the modalities.

- The definition of the “problem” needs to be examined as it will most assuredly be multi-layered, interdependent, and complex. Should we even be attempting to address the future? And what are our goals? To define it? Control it? Learn from it? Limit it? Or, co-create it?

- Throughout all the design steps, we will need to access the greatest aspects of our imagination, intuition, and intelligence—surpassing the sole application of mind-based processes. Our quest is to design the future and to do so in a way that empowers and encourages us to see our current paradigms and assumptions that control our current views of the past, present, and future. This process must allow us to see (and cocreate) a future that does not yet exist—one that cannot be built by simply reorganizing past data and analysis processes. This process must also empower us to simultaneously engage today’s current reality, tomorrow’s emerging opportunities, and the future’s constantly-changing possibilities.

This article is a reduced version of a forth coming chapter that will be published digitally in a book entitled: The Future of Work – An Anthology. My Educator (www.myEducator.com)

About the Authors

Dr. Kristine Marin Kawamura is currently a Clinical Full Professor of Management at the Drucker School of Management, Claremont Graduate University (California, USA). She is also the CEO and founder of Yoomi Consulting Group, Inc., a leadership success and organisational transformation company. Her research, as well as her overall purpose, is focused on transforming leadership, organisations, societies, and individual lives with Care—a core resource for creating extraordinary connection, authenticity, resilience, and engagement in organisations and unlocking new levels of human, technological, and societal impact. www.cgu.edu/people/kristine-kawamura/ or https://yoomiconsulting.com/yoomiq/

Dr. Kristine Marin Kawamura is currently a Clinical Full Professor of Management at the Drucker School of Management, Claremont Graduate University (California, USA). She is also the CEO and founder of Yoomi Consulting Group, Inc., a leadership success and organisational transformation company. Her research, as well as her overall purpose, is focused on transforming leadership, organisations, societies, and individual lives with Care—a core resource for creating extraordinary connection, authenticity, resilience, and engagement in organisations and unlocking new levels of human, technological, and societal impact. www.cgu.edu/people/kristine-kawamura/ or https://yoomiconsulting.com/yoomiq/

Dr. Mario Raich is a Swiss futurist, book author, and global management consultant. He has been a senior executive in several global financial organisations and an invited professor to leading business schools, including ESADE (Barcelona). He is the co-founder and Chairman of e-Merit Academy (www.emeritacademy.com) and Managing Director for the Innovation Services at ”Raich Futures Studies’‘ in Zurich. In addition, he is a member of the advisory board of the Global Future of Work Foundation in Barcelona. Currently, he is researching the impact of cyber-reality and artificial intelligence on society, education, business, and work.

Dr. Mario Raich is a Swiss futurist, book author, and global management consultant. He has been a senior executive in several global financial organisations and an invited professor to leading business schools, including ESADE (Barcelona). He is the co-founder and Chairman of e-Merit Academy (www.emeritacademy.com) and Managing Director for the Innovation Services at ”Raich Futures Studies’‘ in Zurich. In addition, he is a member of the advisory board of the Global Future of Work Foundation in Barcelona. Currently, he is researching the impact of cyber-reality and artificial intelligence on society, education, business, and work.

Dr. Simon L. Dolan is currently a senior professor and researcher at Advantere School of Management (Madrid) and the President of the Global Future of Work Foundation. He was formerly the Future of Work Chair at ESADE Business School in Barcelona. He taught in many North American business schools, such as Montreal, McGill, Boston, and Colorado. He is a prolific author, with over 80 books on themes connected to managing people, culture reengineering, values, coaching, and stress and resilience enhancement. He has also published over 150 papers in scientific journals. He is an internationally sought speaker. His full CV is at: www.simondolan.com

Dr. Simon L. Dolan is currently a senior professor and researcher at Advantere School of Management (Madrid) and the President of the Global Future of Work Foundation. He was formerly the Future of Work Chair at ESADE Business School in Barcelona. He taught in many North American business schools, such as Montreal, McGill, Boston, and Colorado. He is a prolific author, with over 80 books on themes connected to managing people, culture reengineering, values, coaching, and stress and resilience enhancement. He has also published over 150 papers in scientific journals. He is an internationally sought speaker. His full CV is at: www.simondolan.com

Dave Ulrich is the Rensis Likert Professor at Ross School of Business, the University of Michigan, and Partner at the RBL Group (www.rbl.net), a consulting firm focused on helping organisations and leaders deliver value. He studies how organisations build capabilities of leadership, speed, learning, accountability, and talent through leveraging human resources. He has written over 30 books and 200 articles on talent, leadership, organisations, and human resources.

Dave Ulrich is the Rensis Likert Professor at Ross School of Business, the University of Michigan, and Partner at the RBL Group (www.rbl.net), a consulting firm focused on helping organisations and leaders deliver value. He studies how organisations build capabilities of leadership, speed, learning, accountability, and talent through leveraging human resources. He has written over 30 books and 200 articles on talent, leadership, organisations, and human resources.

Claudio Cisullo is a Swiss entrepreneur. During his entrepreneurial career, he founded and established over 26 companies in different business segments globally. He is a Board member of several internationally renowned companies. He is the founder and owner of the family office, CC Trust Group AG, and also the founder and Executive Chairman of Chain IQ Group AG with headquarters in Zurich. Chain IQ is an independent, global service and consulting company.

Claudio Cisullo is a Swiss entrepreneur. During his entrepreneurial career, he founded and established over 26 companies in different business segments globally. He is a Board member of several internationally renowned companies. He is the founder and owner of the family office, CC Trust Group AG, and also the founder and Executive Chairman of Chain IQ Group AG with headquarters in Zurich. Chain IQ is an independent, global service and consulting company.

References

- Delbert C., (2022). There’s a Damn Good Chance AI Will Destroy Humanity, Researchers Say in a New Study. https://www.popularmechanics.com/technology/security/a41507433/stop-ai-from-taking-over/

- See: The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness by Robert Waldinger, MD, and Marc Schulz, PhD, Simon & Schuster (January 10, 2023) and The Good Life, An Interview with Robert Waldinger, https://hms.harvard.edu/magazine/sleep/good-life

- See www.yoomiconsulting.com for practices and guidance to develop this capacity.

- For an overview of the history of design thinking, see https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/design-thinking-get-a-quick-overview-of-the-history#:~:text=Cognitive%20scientist%20and%20Nobel%20Prize,as%20principles%20of%20design%20thinking

- Sundy Grubel, Design Thinking in Real Life, May 9, 2019, https://www.accenture.com/us-en/blogs/software-engineering-blog/sundy-grubel-design-thinking

- A full description can be found in a paper we published in The European Business Review in November 2020: Raich et al: Managing By Traction (MbT) Reinventing Management in the Cyber-Age, https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/managing-by-traction-mbt-reinventing-management-in-the-cyber-age/

- For more, read the work of the philosopher-monk Nagarjuna (c. 2nd-3rd centuries, CE) from the Madhyamaka school. Madhyamaka – Encyclopedia of Buddhism https://encyclopediaofbuddhism.org/wiki/Madhyamaka

- See https://www.deviantart.com/andela1998/art/look-at-life-through-red-tinted-glasses-377908230

- Our study of science, philosophy—and all the systems and knowledge that underlay our thinking and decision-making —are all rooted in context. There are many examples of how new knowledge caused an evolution or even a revolution in thinking about our world. In medicine, shamans believe that illness comes from imbalance, soul loss, entanglement (taking on the energy of others), lineage patterns, or disconnection from the natural world. In the Middle Ages, people believe that “god” controlled everything, thus, god must also send disease and illness. Infectious disease doctors study how the pathogen and host interplay in the infectious disease process. With regards to the Earth and its relationship with the solar system, people used to believe that the centre of the Universe was the spherical, stationary Earth, around which rotated the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets. This view, established by Ptolemy (4th century BC) was only overturned when scientific findings from Copernicus, a mathematician and astronomer, proposed that the sun was stationary in the centre of the Universe and the Earth rotated around it. This controversial perspective also became seen as the start of the Scientific Revolution, which brought ground-breaking shifts to the human conception of the cosmos and humanness itself. The Copernican revolution launched a fundamental cultural transformation away from religious paradigms and towards scientific paradigms.

- See Jörg, Johannes. The Copernican Revolution of the human mind, October 31, 2021. (The Copernican Revolution of the Human Mind | Essentia Foundation) https://www.essentiafoundation.org/the-copernican-revolution-of-the-human-mind/reading/

- For example, once a statement such as, “This is not a pandemic,” is repeated (and by people with high levels of reputation capital or marketplace power) and is reinforced by people’s supporting beliefs and values, a conspiracy theory can transpire. Soon, the speaker and listener hear only this statement, and they seek out information that perpetuates it, blinding them from anything that refutes its core message. Reinforced and dogmatic repetition of any assumption, paradigm, or axiom can build into a false context, believed by many but without a foundation in reason, facts, or the truth.

- Raich M., Eisler R., and Dolan, S.L. (2014) Cyberness: The Future Reinvented, Amazon. https://www.amazon.es/Cyberness-Future-Reinvented-Mario-Raich/dp/1500673382; Raich M., Dolan S.L., (2008) Beyond: Business and Society in Transformation, Palgrave Macmillan.