By Rashmi Anoop Patil and Seeram Ramakrishna

Plastic pollution in our ecosystems, especially the oceans, and its adverse effects on the biota has raised serious concerns in recent years. Research studies and surveys have provided us alarming estimates (Van Sebille et al., 2015) and crucial pieces of evidence, such as (i) more than 12,000 microplastic particles found in just one liter of Arctic ice (Peeken et al., 2018), (ii) plastic bag found as far as 11 km deep in the ocean (Chiba et al., 2018) and so on, indicating the extent of ocean plastic pollution. Consequently, it has affected more than 600 species of marine life (due to entanglements and ingestion) and many are on the verge of extinction (Gall and Thompson, 2015). This status quo is a repercussion of the exponential growth in the production of plastics in the past two decades and the overconsumption of plastics without being conscious of what happens to the discarded plastic.

According to a report published by McKinsey & Company, more than half (~60%) of the plastics leaking into the global waters come from China, the Philip- pines, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia (McKinsey, 2015). Although plastic waste polluting the oceans is generated globally, Asia is documented as a major ‘end- contributor’ to ocean plastic pollution. This is primarily because all the plastic waste collected across the world ends up in developing countries in Asia. Only the recyclables are processed and the remaining plastic mass is dumped in the landfills or thrown into the water bodies, that eventually reach the ocean. But, the trend in Asia related to the importing of plastic waste is slowly changing. Asian countries are becoming aware of the effects of plastic recycling activities on the local environment and the population. There were a few major course changing developments in the recent past and we have put them together in the form of an intriguing discussion for clarity, focused on narratives around the sustainability trends and challenges in plastic waste management in Asia.

What was the most impactful change in the past couple of years that fueled sustainability consciousness in Asia?

China’s ban on plastic waste imports

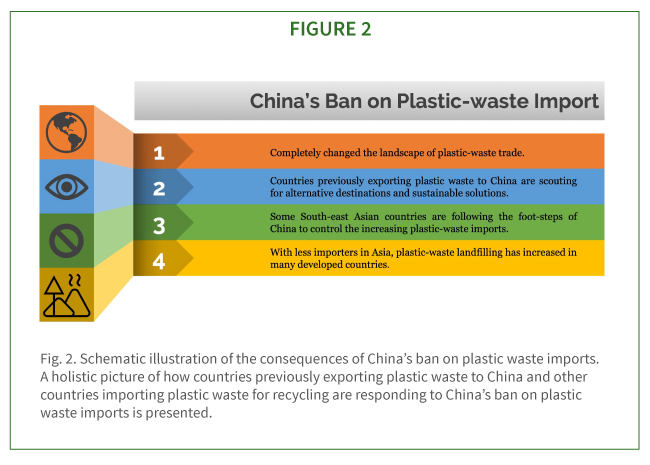

Historically, the Asian countries have been a go-to solution for the West to get rid of the plastic waste they generate. Asia welcomed this business opportunity and over the years, housed the largest plastic recycling market. In 2016, China alone imported two-thirds of the world’s plastic waste (The NGC Report on Plastic Recycling 2018). After more than two decades of importing billions of tons of plastic waste (The NGC Report on Plastic Recycling 2018), the Chinese Government realized the adverse effects of the recycling industry on their environment and enforced a complete ban on imports of any plastic waste since the beginning of 2018 (Eco-Business Report on China’s Plastic Ban 2020). This includes a ban on manufacturing ultra-thin plastic bags, disposable foam plastic tableware and plastic cotton swabs in certain provinces. This was a game- changer for plastic waste trade and recycling businesses, affecting the perception of plastic waste import, especially in low-income countries. All the countries exporting plastic waste (such as the USA, Australia, Japan, and many in Europe) to China (Brooks et al., 2018) now faced a serious issue of getting rid of their plastic waste and started scouting for alternative destinations. In the meantime, the Chinese recyclers found an opportunity to expand their business and set up their recycling units in other South-East Asian countries such as Malaysia where recyclable plastic waste import is still legal (The Business Times Report). Also, plastic waste exports from the West to other Asian countries such as India, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines increased drastically, directly influenced by the China ban. Eventually, these countries were overwhelmed by the amount of incoming plastic waste, that once China used to take in. The world has now reached a stage where production and consumption of plastic have increased so much that managing plastic waste without impacting our ecosystems has become almost impossible.

These developments over the past couple of years have resulted in a series of political, social, and economic changes at a global level. Some of the South-East Asian countries such as Vietnam and Malaysia are following the footsteps of China in banning plastic waste imports. Plastic waste is piling up in the landfills of developed countries previously exporting to China. According to a recent study (Brooks et al., 2018), over the coming decade, more than 100 million tons of plastic waste will have to find a new place to be processed or otherwise disposed of as a result of China’s ban! To tackle this issue, many countries in Europe, Asia and some states in the USA are trying to reduce the consumption of plastic by enforcing regulations and consumer awareness programs (Lam et al., 2018).

Another example that can be given is that of Australia that is creating recycling systems at home to fight the increasing recycling costs and landfilling of plastics. However, Dr. Roland Geyer (at the University of California, author of ‘Production, use and fate of all plastics ever made’) says Plastics never has had a viable business model. Its too low-value, too contaminated, with too many different polymers mixed. And it can only work with a really low cost of labor (The NGC Report on China’s Ban of Trash Import 2018). It’s therefore implied that recycling plastic waste can be a viable business only in low-income countries. Researchers and many start-ups across the globe are trying to provide a multitude of solutions such as bio-based alternatives for single-use plastics, redesigning plastic products taking into account what happens to plastic at its end-of-life, and environment-friendly plastic recycling technologies. Dr. Marc Hillmyer’s research group at the University of Minnesota have reported bio-based plastic alternatives (Martello et al., 2014; Dirlam et al., 2018; Fortman et al., 2018), but are relatively expensive to be introduced into the existing market.

The plastic-waste trade has become unsustainable and hence calls for sustainable solutions. There is a collective need for international law to regulate plastic waste trade. Such a law should strictly impose a rule allowing the transboundary movement of only the sorted recyclable plastics. To abide by this rule, all countries will have to establish infrastructure for proper collection and sorting of plastic waste. Also, producers should be mandated to use a minimum quantity of recycled resin. This will definitely curb environmental pollution by increasing the recycling rate.

What trend can we expect for sustainability in the 2020s that is acute in Asia? How will it affect businesses in the region?

Eradicating Single-use Plastics and Building Zero Plastic-waste Cities

Asia, especially in the cities, is grappling with a growing throwaway culture. Plastics being an inexpensive material has invaded the Asian lifestyle and by far is the most discarded. Subsequently, this has contributed to an enormous rise in the domestically generated plastic waste, and the respective governments have acknowledged and are trying to find a solution to this crisis. For example, countries such as India, China, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Malaysia are curbing the production and consumption of polyethylene (plastic) bags by enforcing bans (UNEP, 2018). Beijing and Jakarta are trading plastics for train rides! However, these steps, even though being in the right direction, have fallen short in confronting the issue effectively. There is a need for an entirely new approach to tackle this problem and one such approach can be harnessing a combination of innovative technologies and the rising conscious consumerism. Asia could incubate the new emerging business models that reduce plastic production and minimize the stress on future waste management systems.

Major stakeholders such as businesses generating plastic waste are slowly steer- ing towards plastic alternatives such as paper, wood, and glass for packaging. Con- scious consumerism is on the rise marked by an increase in refusal of single-use plastics and opting for non-plastic alternatives. For example, a few supermarkets in Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines are embracing eco-friendly banana leaves to wrap fresh produce as an alternative for plastic packaging (Forbes 2019, Ecowatch 2019, Vice 2019). Some supermarket chains in Asian countries have introduced a fee for single-use plastic bags (TODAYonline 2018, The Japan Times 2019, Jakarta Globe 2016). Food and Beverage businesses are embracing paper cups and wooden cutlery instead of plastic counterparts (TODAYonline 2019, Starbucks 2019, Nestl´e 2019). Conscious consumerism by choice thus is quintessential to move away from a plastic society.

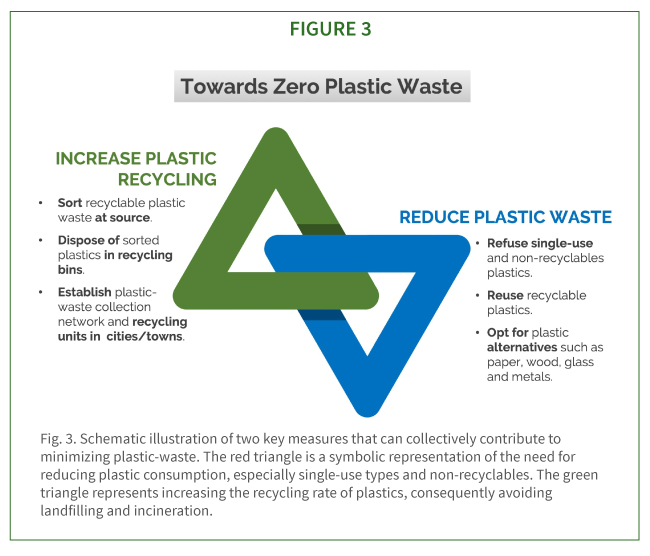

Sporadic green initiatives by businesses cannot be a holistic solution to the Asia’s plastic waste crisis. The region needs a strong framework and public co-operation to slowly eradicate single-use plastics which will consequently lead to better plastic recycling rates. The most efficient way to control the consumption of single-use plastics is to minimize its production and imports to start with. This in turn, will make the businesses and consumers adopt eco-friendly, alternative ways to overcome their habitual and convenient usage of single-use plastics. Such an initiative can reduce the amount of waste significantly and lower the burden on recycling. However, there will always be resistance from the manufacturers to adopt this change. Even though the manufacturing industry will be affected, this change is necessary for the sustainability of our ecosystems in the long run.

Once the single-use plastics are minimized, it is feasible for the towns and cities to progress towards the zero-plastic waste goal. For a zero-plastic waste society, the current plastic recycling rates should significantly increase. To do so, local governing authorities should develop a proper plastic waste collection network and formal sorting and recycling units for creating a closed-loop of plastics. Several ASEAN cities are working in this direction towards becoming a zero-waste society. In the Philippines, San Fernando is considered as a zero-waste model, with more than 90% of the waste diverted from landfills to recycling in 2019 (Manila Standard 2019)! In Indonesia, the West Java cities namely Bandung, Cimahi, and Soreang have started piloting zero waste projects (The Jakarta Post 2019). In Malaysia, Penang is driving a zero plastic-waste initiative in several residential apartments and schools (Down to Earth 2019).Vietnam is also planning to start its pilot project of zero plastic-waste city (World Economic Forum 2020). Singapore announced zero-waste master plan in 2019. Reduction of plastic waste and higher recycling rates are notable aims of the new policy (MEWR, 2019). Such projects should inspire the governments of other cities or towns to implement suitable models from the pilot projects, to reduce landfilling and increase recycling. The trend of zero-waste cities has set in, and now, it has to gain momentum.

Plastics management was a hot topic in 2019. What are the major challenges in plastic waste management, handling, and materials circular economy?

Social and Economic Challenges

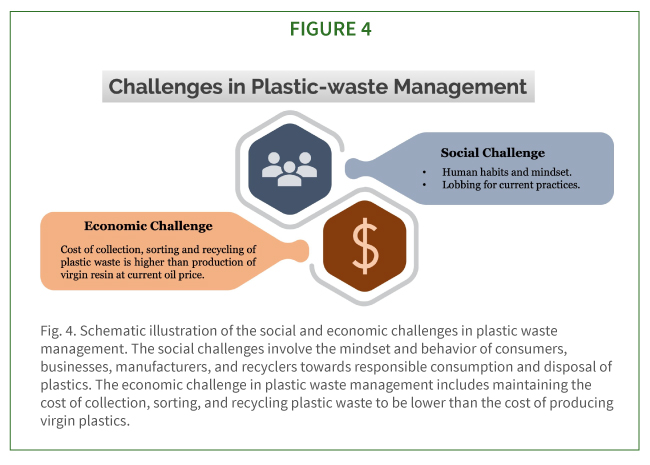

A study estimated the global production of virgin plastic resins and fibers has been more than 300 million tons annually in recent years (Geyer et al., 2017). To add to this, less than 10% of all plastics ever produced have been recycled and the remaining is landfilled or incinerated (Geyer et al., 2017). If the current trends are followed, according to recent estimates, plastic production and incineration could emit over 6.5 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2050, accounting for 15% of the total carbon budget we can ‘spend’ by mid-century under the current trajectory (Zheng and Suh, 2019). While efficient waste management and recycling processes are both imperative, the only real and lasting solution is to produce less plastic in the first place. However, it is an uphill task to implement it as there are several social and economic challenges to overcome.

Human mindset and habits are difficult to change. Creating social awareness to transform societal behavior is a time-consuming and evolving process. However, this is critical when it comes to reducing plastic usage. Although conscious consumerism is on the rise, it is restricted to certain regions or particular sections of society and is sporadic too. As plastics are inexpensive, easy to manufacture on a large scale and convenient to use for daily tasks, it is usually preferred by the manufacturers, vendors and consumers alike. Moreover, they are accustomed to single-use plastics and are reluctant to change. Creating awareness about the harmful effects of plastics on human health and the environment at the grass-root level of society and urging people to use traditional materials from the pre-plastic era is the only way. If in the long-run, we are successful in convincing communities to reduce plastic usage and making them plastic-conscious, the demand for plastics automatically decreases, subsequently impacting the production. A sensitive hurdle for this transition lies with the manufacturer’s lobbying, which advocates the benefits of plastics, blaming other stakeholders such as the consumers for their improper disposal procedures, and the waste management authorities for inefficient practices, in order to save their existing business.

Economics is a major factor in shaping the way business functions. Any business progression happens if it seems to be economically viable. In the case of managing plastic waste, as stated earlier, maintaining the cost of collection, sorting, and re- cycling to be lower than the cost of producing virgin plastic is truly challenging at the current oil prices. Treating plastic waste generally assumes a high cost either because of the labor or the technologies that replace human labor and automate the management flow. The only solution to this issue is responsible consumerism. In addition to reducing plastic consumption, consumers have to sort the recyclables and dispose of them responsibly so that the sorting process can be skipped after collection.

Research shows that aggressive implementation of a combination of multiple strategies is needed in order to curb GHG emissions from plastics (Zheng and Suh, 2019). The 3Rs – reduce, reuse and recycle – strategy should be followed globally to mitigate GHG emissions. Research indicates that renewable energy usage in plastic production and the adoption of bio-based plastics are also essential in cutting down emissions (Zheng and Suh, 2019).

Authors’ Opinion

We are all aware of the environmental hazards caused by the use and disposal of single-use plastics. Still, we end up using them every day. Not that we do not have better choices. It all comes down to our reluctance to adopt change as we are very much used to the ease of using single-use plastics. When we shop for groceries or in general any consumables at a supermarket or buy some clothing and fashion accessories, we end up bringing home a bunch of (single-use) plastic bags. Eventually, these bags are either landfilled or incinerated polluting the environment. And consequently, we become a part of climate change, every single time this happens. The Whole Foods Market, an American multinational supermarket chain is well known for giving paper bags at the checkout counters across all stores. They have been providing 100% recycled and 100% recyclable paper bags for more than a decade now (Wholefoods 2009). Recently, the popular fashion brands such as Zara, H&M, Uniqlo, and Cotton On (Cotton On 2019) have switched to eco-friendly paper shopping bags. This means, no single-use plastic bags!

Such ecological consciousness can be an inspiration for us to ditch the single-use plastic bags and carry reusable non-plastic bags for shopping. Change in consumer behavior also stems from being aware of the plastic footprint on the environment and hence, the change should be inspired and not enforced.

Single-use plastics has invaded the Food and Beverage industry. Whenever one orders food online or get a takeaway from a restaurant/food court, the food is generally packaged in plastic. Even the cut fruits, fresh juices, and beverages which we grab on the go are, at so many places, still being served in single-use plastic cups. This plastic packaging is a major part of trash in many households and a very small portion of this plastic packaging waste is recycled. We all know that the incineration of these plastics causes environmental hazards due to the emission of toxic persistent pollutants such as dioxins, furans, polychlorinated biphenyls, halogens, and heavy metals into the atmosphere (Verma et al., 2016). But what we as consumers don’t realize when we use plastic is how harmful they (the plastic material and its toxic derivatives upon incineration) are to our health. Research has well established the fact that the ingestion of many chemical plasticizers with food, even in very small amounts is too bad for our health in the long run (Ghisari and Bonefeld-Jorgensen, 2009; Erythropel et al., 2014). These chemicals are endocrine disruptors that can cause hormonal and reproductive issues (Ghisari and Bonefeld-Jorgensen, 2009) and also be a cause of cancer (Selenskas et al., 1995).

Some of the businesses such as Starbucks, McDonald’s and many other beverage outlets are trying to reduce single-use plastics by avoiding plastic straws and cups. They have replaced plastics with reusable straws made from either bamboo or steel, or disposable paper straws, and hard paper cups for serving drinks. Some of them provide wooden stirrers and cutlery. Starbucks is also encouraging customers to bring their own cups. Such initiatives should be further encouraged for collective public behavior, which will eventually impel other businesses also to change to ecofriendly sustainable options.

So let us change; some small changes in our lifestyle for a healthier future. For example, we can start by carrying around a non-plastic water bottle to avoid using single-use mineral water bottles. Instead of getting a takeaway or food delivery, we can eat at the restaurants/food courts and insist the vendors/owners serve food in porcelain, steel or bio-based crockeries. We can also consciously avoid plastic pack- aging by opting for paper, glass, or metal packaging while buying fresh produce and groceries. Such practices will, in the long run, save the environment and eventually us.

Even with all the conscious efforts to refuse single-use plastics, we are bound to end up using them a few times here and there. In such cases, we should make sure to dispose of them in the plastic recycle bins rather than the general bins to avoid incineration and landfilling. Steps should be taken up to segregate the recyclable plastic waste at the source (households and businesses) for recycling. Moreover, studies show that recycling plastic waste saves more energy (by reducing the need to extract fossil fuel and process it into new plastic) than incinerating them in a waste-to-energy plant. All these efforts, however small, will also help lower the per capita carbon emission.

Apparently, all these efforts to reduce the usage of single-use plastics when considered individually may seem minor or ineffective. However, when considered collectively in the scale of a densely populated city or even globally, it makes a significant difference. This is just a beginning. A systematic research is to be funded and carried out to evaluate the impact of different materials options on our ecosystem. We need to make many more tiny changes in our lifestyle and choices to lower overall plastic and carbon footprint in order to enable Earth as a healthier and greener planet.

Welcome Change. Start Small. Go Green.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Anoop C. Patil from the N.1 Institute for Health, National University of Singapore, for his valuable suggestions to improve this article. The authors also acknowledge the participants of the round-table discussion on ‘Ocean Plastics Pollution: Research and Innovative Solutions’, at the Asia Pacific Sustainability Development and Circular Economy Innovations Forum 2020 (http://claridenglobal.com/conference/apac-sustainability-development-sg/; February 4, 2020) held at Grand Hyatt, Singapore. This discussion was facilitated by the first author of this work and the insights shared in this discussion have helped in shaping the Authors’ Opinion section of this article.

About the Authors

Rashmi Anoop Patil, (Email: rashmi.anoop33@gmail.com) is a circular economy enthusiast and an engineer by profession with a Bachelors in Electronic Engineering from Visveswaraiah Technological University, India. As a member of the Circular Economy Task Force at the National University of Singapore (NUS) (led by Prof. Seeram Ramakrishna, Chair, Circular Economy Task Force, NUS), she is currently researching on Circular Economy concepts and has developed research reports on Singapore’s pursuit of circular economy, worldwide e-waste management legislations, and the current trends in solutions for the ocean plastic problem. She is passionate about sustainability development and ecofriendly businesses.

Rashmi Anoop Patil, (Email: rashmi.anoop33@gmail.com) is a circular economy enthusiast and an engineer by profession with a Bachelors in Electronic Engineering from Visveswaraiah Technological University, India. As a member of the Circular Economy Task Force at the National University of Singapore (NUS) (led by Prof. Seeram Ramakrishna, Chair, Circular Economy Task Force, NUS), she is currently researching on Circular Economy concepts and has developed research reports on Singapore’s pursuit of circular economy, worldwide e-waste management legislations, and the current trends in solutions for the ocean plastic problem. She is passionate about sustainability development and ecofriendly businesses.

Prof. Seeram Ramakrishna, FREng is the Chair of Circular Economy Taskforce at the National University of Singapore, NUS. He is a member of the Enterprise Singapore’s NMC on ISO/TC323 for Circular Economy. He is an advisor to the Singapore National Environmental Agency’s CESS events. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Springer Nature Journal Materials Circular Economy. He is an editorial board member of Nature Scientific Reports. He is a co-organizer of the NSF, USA sponsored conference on materials and circular economy. He chairs the Future of Manufacturing Group, Institution of Engineers Singapore. His leadership roles include NUS University Vice-President (Research Strategy); Dean of NUS Faculty of Engineering; Director of NUS Enterprise; and Founding Chairman of Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore, SERIS. He is an elected Fellow of UK Royal Academy of Engineering (FREng); Singapore Academy of Engineering; Indian National Academy of Engineering; and ASEAN Academy of Engineering & Technology. He received PhD from the University of Cambridge, UK and the TGMP from the Harvard University, USA. He is named among the World’s Most Influential Minds by Thomson Reuters, and among the Top 1% Highly Cited Researchers in the world by Clarivate Analytics. A European study placed him among the only 500 researchers with H index above 150 in the history of science and technology.

Prof. Seeram Ramakrishna, FREng is the Chair of Circular Economy Taskforce at the National University of Singapore, NUS. He is a member of the Enterprise Singapore’s NMC on ISO/TC323 for Circular Economy. He is an advisor to the Singapore National Environmental Agency’s CESS events. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Springer Nature Journal Materials Circular Economy. He is an editorial board member of Nature Scientific Reports. He is a co-organizer of the NSF, USA sponsored conference on materials and circular economy. He chairs the Future of Manufacturing Group, Institution of Engineers Singapore. His leadership roles include NUS University Vice-President (Research Strategy); Dean of NUS Faculty of Engineering; Director of NUS Enterprise; and Founding Chairman of Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore, SERIS. He is an elected Fellow of UK Royal Academy of Engineering (FREng); Singapore Academy of Engineering; Indian National Academy of Engineering; and ASEAN Academy of Engineering & Technology. He received PhD from the University of Cambridge, UK and the TGMP from the Harvard University, USA. He is named among the World’s Most Influential Minds by Thomson Reuters, and among the Top 1% Highly Cited Researchers in the world by Clarivate Analytics. A European study placed him among the only 500 researchers with H index above 150 in the history of science and technology.

References

• Brooks AL, Wang S, Jambeck JR (2018) The Chinese Import Ban and its Impact on Global Plastic Waste Trade. Science Advances 4(6):eaat0131

• Chiba S, Saito H, Fletcher R, Yogi T, Kayo M, Miyagi S, Ogido M, Fujikura K (2018) Human footprint in the abyss: 30 year records of deep-sea plastic debris. Marine Policy 96:204–212

• Dirlam PT, Goldfeld DJ, Dykes DC, Hillmyer MA (2018) Polylactide foams with tunable mechanical properties and wettability using a star polymer architecture and a mixture of surfactants. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 7(1):1698–1706

• Erythropel HC, Maric M, Nicell JA, Leask RL, Yargeau V (2014) Leaching of the plasticizer di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) from plastic containers and the question of human exposure. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 98(24):9967–9981

• Fortman DJ, Brutman JP, De Hoe GX, Snyder RL, Dichtel WR, Hillmyer MA (2018) Approaches to sustainable and continually recyclable cross-linked polymers. ACS Sus- tainable Chemistry & Engineering 6(9):11145–11159

• Gall SC, Thompson RC (2015) The impact of debris on marine life. Marine Pollution Bulletin 92(1-2):170–179

• Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL (2017) Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science Advances 3(7):e1700782

• Ghisari M, Bonefeld-Jorgensen EC (2009) Effects of plasticizers and their mixtures on estrogen receptor and thyroid hormone functions. Toxicology Letters 189(1):67–77

• Lam CS, Ramanathan S, Carbery M, Gray K, Vanka KS, Maurin C, Bush R, Palanisami T (2018) A Comprehensive Analysis of Plastics and Microplastic Legislation Worldwide. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 229(11):345

• Martello MT, Schneiderman DK, Hillmyer MA (2014) Synthesis and melt processing of sus- tainable poly (ε-decalactone)-block-poly (lactide) multiblock thermoplastic elastomers. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2(11):2519–2526

• McKinsey (2015) Stemming the Tide: Land-based strategies for a plastic-free ocean. McK- insey Center for Business and Environment and Ocean Conservancy pp 1–48

• MEWR (2019) Zero Waste Masterplan Singapore, Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources [Online; accessed 10-Feb-2020]

• Peeken I, Primpke S, Beyer B, Gu¨termann J, Katlein C, Krumpen T, Bergmann M, Hehemann L, Gerdts G (2018) Arctic sea ice is an important temporal sink and means of transport for microplastic. Nature Communications 9(1):1–12

• Selenskas S, Teta MJ, Vitale JN (1995) Pancreatic cancer among workers processing syn- thetic resins. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 28(3):385–398

• UNEP (2018) Single-use Plastics: A Roadmap for Sustainability pp 1–104

• Van Sebille E, Wilcox C, Lebreton L, Maximenko N, Hardesty BD, Van Franeker JA, Eriksen M, Siegel D, Galgani F, Law KL (2015) A global inventory of small floating plastic debris. Environmental Research Letters 10(12):124006

• Verma R, Vinoda K, Papireddy M, Gowda A (2016) Toxic Pollutants from Plastic Waste -A Review. Procedia Environmental Sciences 35:701–708

• Zheng J, Suh S (2019) Strategies to reduce the global carbon footprint of plastics. Nature Climate Change 9(5):374–378