By David Dubois and Gilles Haumont

With the wave of increasing digital footprints in today’s technology-driven business landscape, more and more brands are stepping up their efforts in terms of harnessing data and extracting value from it. This article presents the next big thing about branding that is shaping consumer-driven data analytics.

Ancient romans depicted their god of time and transition, Janus, as having two faces – one looking into the past and the other into the future. Very much like Janus, most digital disruptions are two-sided; they bridge the (recent) past with the future, offering ever-increasing opportunities to build customer relationships. They indeed accumulate information from our past digital behaviours – from whom we talked to on social media to how we search and shop for products or the route we chose to go to work. This corpus of data is simply the largest repository of information ever produced – an open diary reflecting individuals’ thoughts, wants, fears, aspirations and feelings that brands can leverage to create future value.

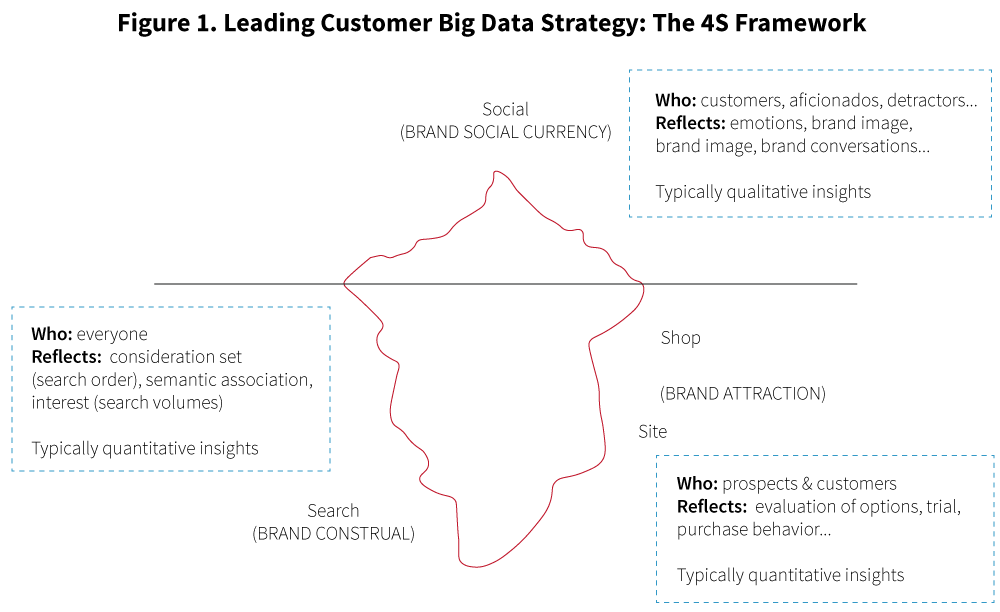

In a digital world, the difference between success and failure increasingly rests on brand leaders’ ability to (1) understand and (2) act on digital insights.1 A useful analogy to unpack big data is to think about each bit of data (e.g., a search, a geotag log into social network, an email) as a footprint that customers leave along their journey. As of today, brand leaders can easily access/collect four main types of footprints, which we refer to as the 4S framework (see figure 1 ): social media behaviours (i.e., interactions with public content from social ç such as Twitter or Instagram), search behaviours (i.e., search queries performed on search engines about the brand/category), site behaviours (i.e., visitor pathways on the brand and associated websites) and shop behaviours (i.e., shopping activity on e-commerce platforms or one’s own website).

Social media behaviours, from Facebook and Twitter to Instagram, represent rich multi-support qualitative insights for brand strategists (images, likes, shares, etc.). This type of strategy is best implemented by a professional digital marketing agency. Social media behaviours are performed in a public context and as such reflect social perceptions about brands and individuals – in a nutshell, a brand’s social currency. For instance, the nature and type of emojis used by consumers when talking about what specific brands represent reflect the social emotions attached to the brand. The diversity of footprints – images, shares, reviews – provides deep insights into how the public may perceive, relate and express its feelings about a brand. Similarly, brands aiming to change their image and communication can easily use social media data from public conversations when assessing the effectiveness of a campaign on brand image. Above and beyond measuring brand sentiment, a brand may be able to assess changes in the language used about a brand. In practice, many social media analytics tools from Digimind to NetBase or Brandwatch provide an easy window to this social, visual information that brand managers can leverage and integrate to their marketing organisation.

With several trillion searches per year, search queries on search engines such as Google or Baidu represent today the largest “data lake” reflecting customer intentions. While social media behaviours are performed in a public context, search behaviours tend to mirror individuals’ private interests (search behaviours are, by nature, private), and as such reflect personal interest for brands. Beyond the sheer size of search for a brand – indicative of personal interest in the query, search insights – associated keywords, keyword order, keyword history – can yield rich insights about the cognitive structure and semantic associations of brands – what we call, brand construal. For instance, what competitors or action verbs are associated with specific keyword. Unpacking such information can yield rich insights into a brand’s consideration set. Alternatively, uncovering the action verbs associated with a brand or a type of banking services may help understand the type of goals that consumers associate with them. For instance, a consumer may indicate a goal to save or spend when searching for a specific bank (e.g., “brand X savings rate” vs. “brand X withdrawal limit”) thus indicating the type of goal he or she has in mind when interacting with the bank. From this perspective, understanding groups of consumers’ search journey can provide highly valuable information about their interests. In practice, aside from Google tools (e.g., Trends, AdWords) and their equivalent at Baidu or Bing, many SEO or SEM solutions such as KWFinder offer treasure troves of information about up-to-date and (often) geography-specific search volumes and associated keywords.

Site and shop behaviours are the most direct footprints of brand attraction – that is, a brand’s ability to attract customers into a purchase funnel. Site behaviours (length of visit, interaction on website etc.) typically speak to how consumers prepare the act of purchase by collecting brand information, browsing a collection including alternative and complementary options, learning about the brand’s point of differentiation or gaining knowledge on how a product (e.g., a car) was made. Given that brands can readily access information about their sites’ visitors and the journey they follow on the site, these types of footprints represent low-hanging fruits in the brand strategist toolkit. Similarly, shopping behaviour that reflect actual purchases can provide easy and quick feedback on the market’s response. Of note, shop behaviours may come from direct (e.g., online sales) or indirect (e.g., stock out data) information collected from one’s or competitors’/retail partners’ e-commerce platforms.

Although the importance of each footprint and the nature/amount of data available may vary across industries, the approach applies to all contexts – from B2B to B2C with each footprint providing a different perspective on how a brand, product or service, is understood, liked, and bought. To illustrate, healthcare professionals’ digital footprints may yield rich insights into how they use digital sources when taking medical decisions. Similarly, industrial products manufacturers (e.g., chemicals, textiles, machines, and equipment) may uncover why and when their customers are drawn to their products / product category and thus implement more effective segmenting, targeting, and positioning campaigns within their value chain. Some data mining solutions such as Tsquared Insights or IBM Watson offer access to all types of information of tens of millions of consumers (anonymised) history that helps identify their needs, attitudes values and even shopping behaviours for purposes of innovation or consumer profiling. Because they are based on behavioural segmentation, these new techniques effectively uncover new tribal clusters based on lifestyles (i.e., how people digitally behave, both individually and socially).

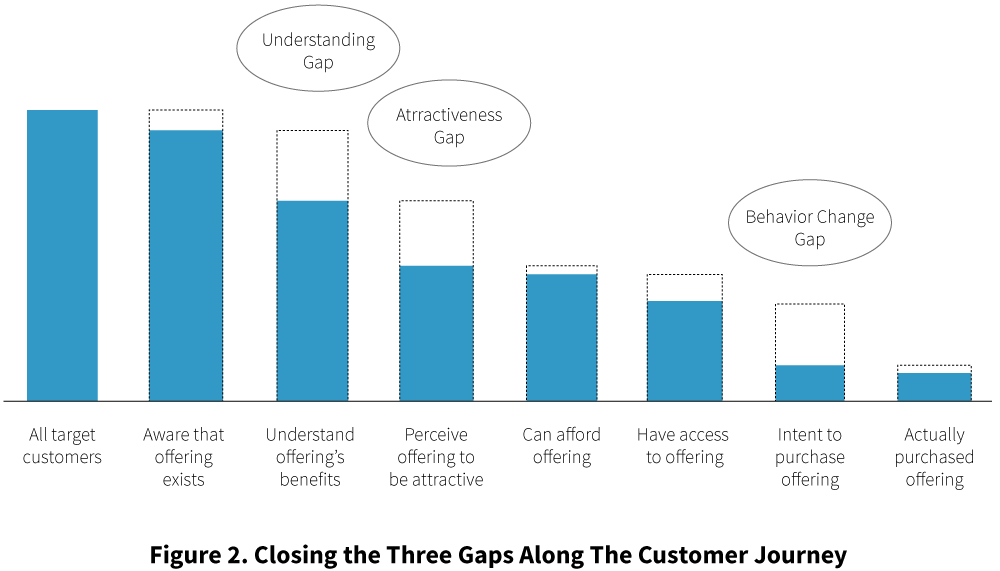

Altogether, search, social, site and shop behaviours yield quantitative and qualitative information about customers along their journey which illuminates three important “gaps” that can make the difference between failure and success. Specifically, a brand may suffer along the funnel when customers: (1) do not understand the brand and what it means in the first place (understanding gap), (2) do not form positive attitudes towards the brand (attitude gap), or (3) do not change their behaviour towards the brand (i.e., buy the product; alter their consumption habit; the behaviour gap). Let us turn to recent examples of how digital footprints can help brand leaders to close the understanding, attitude and behaviour gaps.

Closing of the understanding gap

Knowing how different audiences think about brands is instrumental in creating competitive advantages in a digital world. Although social media can help unpack brand construal (in particular, with respect to how a brand is thought and talked about in a public context), search data is typically more helpful to unpack consumers’ cognitive structures and semantic associations about brands, both because (1) the size of search data is significantly greater than that of social media data and (2) the nature of search queries is well adapted to reveal a customer’s intention when searching a brand.

Words used in conjunction with a target brand (e.g. L’Oréal) or product (e.g., shampoo) can accurately reveal the mindset consumers have when searching for goods and can subsequently be used in brand communication. To illustrate, Humphreys and colleagues2 found that consumers express where they are in the purchase funnel with their searches: consumers’ search queries tend to be abstract at the beginning of the customer journey (e.g., “what if the best stain remover for red wine?”) but concrete when closer to the purchase (e.g., “where can I buy Tide to Go Pen?”). These differences yield important behavioural consequences, with consumers thinking abstractly [concretely] being (1) more likely to click on paid [organic] search results, and (2) more likely to click on an ad that matches their position in the funnel revealed by their search pattern.

As a second recent use of digital footprints in research, Ordabayeva and Fernandes (2018) showed that the implications of political ideology for different types of luxury products – that help people to differentiate themselves from others vertically vs. horizontally – was reflected in systematic differences in the search terms most used in Republican vs. Democrat states respectively. As one example, search queries for Ralph Lauren (identified as a vertical differentiator) were higher in Republican than Democrat counties, the reverse pattern was found for Urban Outfitters (identified as a horizontal differentiator). Overall, digital footprints such as search represent a rich reservoir that can significantly deepen our understanding of brand construal.

Closing of the attitude gap

A second key gap that digital footprints help close is the extent to which an audience likes a target brand or a product, a necessary step before the purchase. Analysing public footprints (e.g., brand sentiment) represents a powerful tool providing counterintuitive insights on where and why people like certain brands or products. For instance, in the luxury sector, one may expect consumers to hold more favourable attitudes and talk more about positional brands in richer than poorer geographies because consumers are more acquainted with these brands in the former than the latter. However, upon analysing millions of posts on the microblogging platform Twitter for mentions of high- and low-status brands, Walasek and colleagues3 found that luxury brands such as “Louis Vuitton” and “Rolex” were more frequently mentioned in tweets originating from U.S.’ states, counties, and major metropolitan areas with higher levels of income inequality. Using sentiment analysis, they found higher valence (positivity) and arousal (excitement) for tweets that both mention high-status brands and originate from regions with high levels of income inequality. These results corroborate the idea that the positional value of luxury brands (that is, their ability to help consumers “stand-out”) is instrumental in shaping their sentiment vis-à-vis these brands.

Similarly, e-reputation has become the main KPI in several industries. For instance, in the hotel industry, e-reputation accurately predicts visitors’ subsequent intent to book hotels. As a result, tracking reviews and comments systematically becomes of utmost importance. International groups as Accor have thus created systems that systematically track e-reputation (positive and negative review scoring, but also a lot of qualitative comments analysis) that helps them address potential issues in real time and provide value in the form of greater customisation.4

Example of the behaviour gap

Finally, digital footprints are instrumental in helping brand leaders find out why people don’t do what they say they would do. From this standpoint, contrasting search (private interest) and social media (public interest) can shed light on why consumers may not choose certain options even when they are socially desirable. In addition, contrasting shop footprints online with other behavioural indices from search and social media may indicate where consumers dropped in the funnel. At other times, careful analyses of search patterns may reveal subtle differences in an audience’s consideration set. For instance, Stephens-Davidowitz5 showed that the order in which voters’ search for candidates during the 2012 U.S. election (i.e., “Trump vs. Clinton” or “Clinton vs. Trump”) in fact reflected voters preference (for the first of the two candidates searched) and predicted county-level actual votes. Such analyses may be applied to any industry to uncover preferences within an audience’s consideration set. Overall, effective branding increasingly requires: (1) establishing a typology of relevant footprints in the context (4S framework), (2) mapping the footprints along the customer journey, an exercise specific to every brand and (3) integrating digital footprints in the brand organisation to gain competitive advantages in the form of greater customisation, brand extension, or communication effectiveness.6 In a world where digital is the largest open diary of the world’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours, brand strategists have no choice but to place data at the heart of their value creation processes.

About the Authors David Dubois is Associate Professor of Marketing at INSEAD and Programme Director of Leading Digital Marketing Strategy, one of the school’s executive development programmes. You can follow him on Twitter @d1Dubois. Gilles Haumont is Vice President, Luxury & Strategy, at TSquared Insights References 1. Dubois, David (2017). “The Three Types of Big Data That Matter for CMOs” INSEAD Knowledge (September); Stephens-Davidowitz, S. (2017). Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are; HarperCollins 2. Humphreys, Ashlee, Mathew S. Isaac and Rebecca Jen-Hui Wang (2018). “Understanding the Relationship between Top of the Funnel Search Activities and CPG Purchase,” Chicago, IL: Intent Lab Working Paper. 3. Walasek, Lukasz, Bhatia, Sudeep and Brown, G. D. A. (Gordon D. A.). (2018). Positional goods and the social rank hypothesis: income inequality affects online chatter about high and low status brands on Twitter. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 28 (1). pp. 138-148. 4. Dubois, David, Inyoung Chae, Joerg Niessing and Jean Wee, “AccorHotels and the Digital Transformation: Enriching Experiences through Content Strategies along the Customer Journey,” INSEAD Case 08/2016-6241 and Teaching Note 08/2016-62415. 5. Stephens-Davidowitz, S. (2017). Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are; HarperCollins 6. Dubois, David (2016). “The Building Blocks of Digital Transformation: Intelligence, Integration and Impact”, The European Business Review (September).