By Mark Purdy and Ladan Davarzani

To capture the benefits of Internet-connected machines, national leaders must nurture the conditions that are needed to translate technological change into economic growth.

Call it the multi-trillion-dollar question: can the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) jumpstart the lacklustre global economy, which is still struggling seven years after the onset of the Great Recession?

Many government leaders hope the answer is yes. For example, Prime Minister David Cameron wants the UK to lead this ‘new industrial revolution’ and has directed nearly US$125 million to IIoT research. In China, the government has designated the Internet of Things an‘emerging strategic industry’ and plans to invest some US$800 million in the IIIoT by 2015. These and several other governments are looking to the IIoT as a means to stimulate national competitiveness and economic growth.

And with good reason: the IIoT—a vast network of Internet-enabled devices that interact with each other and with their human operators—has the potential to help overcome structural barriers to faster growth. The IIoT could contribute US$14.2 trillion to world output by 2030, according to Accenture’s analysis.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Why such optimism? The IIoT can boost productivity, drive the emergence of new markets, and encourage innovation. In manufacturing, connected sensor networks already monitor logistics movements and machines at mining operations and utilities plants, helping organizations reduce costs. In agriculture, similar networks deployed on farmlands are improving the use of natural resources and contributing to better harvests. The IIoT is also creating entirely new markets in areas such as digital health and ‘connected lifestyle’ products.

But optimistic predictions won’t become reality without a lot of hard work. And when we look at national economies, we see that government leaders and policy makers are going to have to take many steps to ensure that technological change gets translated into economic growth.

Before we get to that, however, let’s take a look at a historical example that sheds light on the challenge that lies ahead.

To Whose Benefit?

With IIoT technologies already reshaping industries, optimism about global economic growth seems warranted. But when one thinks in terms of national economic growth, there is reason for concern. Historically, some countries have been able to capitalize on the economic potential of new technology better than others. This trend may play out again with the IIoT.

Take the introduction of electrification in the industrialized world at the turn of the twentieth century. Although many countries were initially at the same level of technological development, the US became the world leader in electrification because it embedded the new technology in the wider economy and changed production and organizational structures to take advantage of it.

Consider the electrification of factories. Before electrification, factory workers moved around static work stations before finally bringing the different parts of the product together. Electrification turned this concept on its head, with the product moving down a central assembly line while workers remained static, saving thousands of hours in labour costs and permitting greater standardization of activities. By the 1920s, American industries were constructing new all-electric factories in line with the recommendations of industrial engineers, and were retraining factory workers for the new environment.

As the decades progressed, electricity expanded beyond industrial sites to influence the consumer economy. By the 1950s, 94 percent of American families had electricity in their homes, fuelling strong demand for electrified household appliances.

This example shows that technological diffusion is not the same as the economic diffusion of a technology. Technological diffusion is much narrower in scope: the term covers the invention, availability and adoption of a technology. Economic diffusion comes about through significant value-creating changes in production and consumption activities—new ways of organizing the supply chain, running a factory, or selling to consumers, for example.

Consider social media today. Although this technology is widely available and used by billions of people (for instance, through networking sites such as Facebook and Snapchat), only a small fraction of social media users are currently generating economic value from it. Few businesses have fundamentally reinvented their approach to, say, work processes or marketing and sales to take advantage of this technology.

Spreading the Wealth

If countries do not recognize this difference and fail to create enabling conditions for economic diffusion, they run the risk of losing out on the economic potential of the IIoT.

We see these conditions in terms of a country’s ‘national absorptive capacity.’

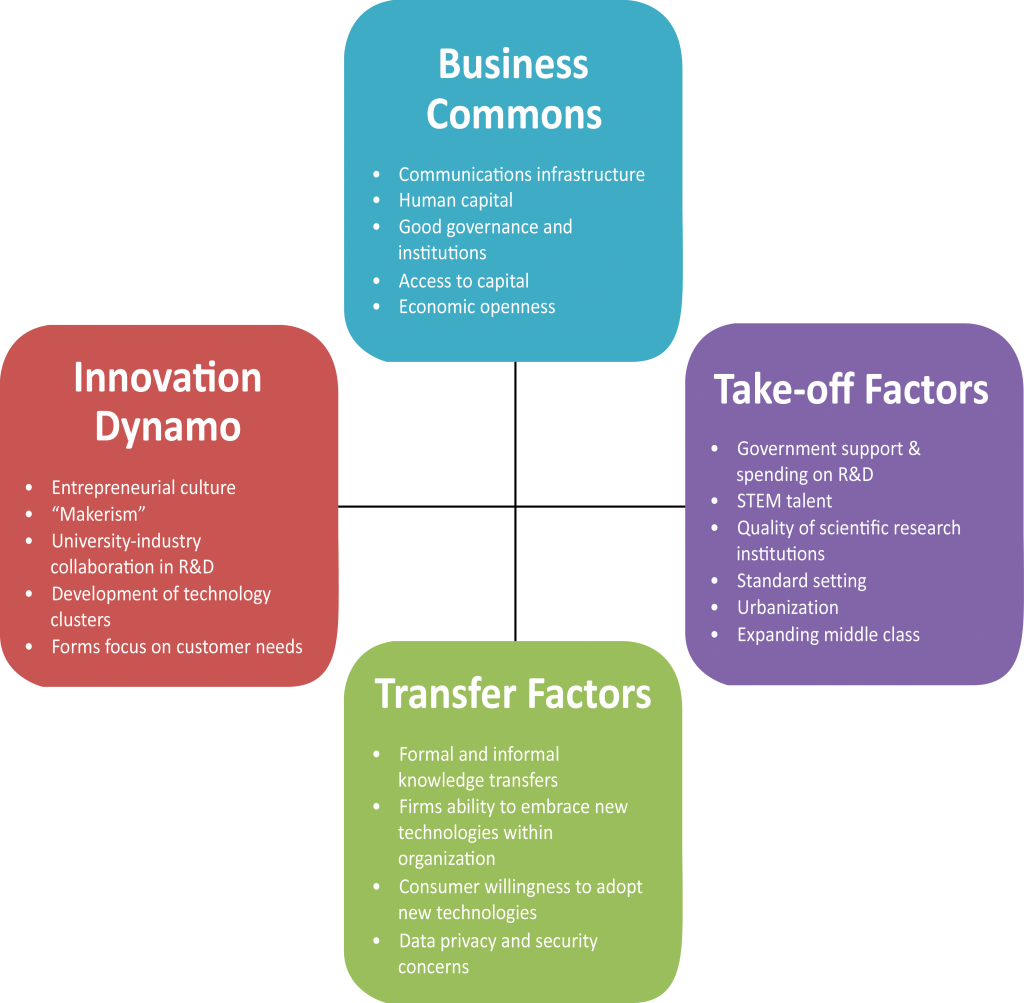

Through our research into previous eras of technological revolution and interviews with experts from technology, economics and business, we identified four enabling conditions for national absorptive capacity. (See Figure 1.) The impact and progress of economic diffusion is determined by the relative strength of these components.

Figure 1

Figure 1: Reaching the Economic Potential of the Industrial Internet of Things

Government leaders can’t take for granted that their nations will enjoy economic growth thanks to the IIoT. To make growth possible, they’ll have to shift their attention away from the technology itself and toward the conditions that convert technology diffusion into economic diffusion. The four-component model below reveals what countries need in order to enjoy the greatest benefits from the IIoT.

Establishing the Business Commons

Building on a technological foundation, countries must create a sound ‘business commons.’ Key ingredients include an educated population, a reliable system of banking and finance, a healthy network of local suppliers and distributors, all working under conditions of good governance and rule of law. A strong telecommunications and Internet infrastructure magnifies the effects of these factors.

Although they have room for improvement, countries in the developed world already have a well-developed business commons. Many countries in the developing world, however, are still working to establish a technological base for the Internet. However, they should also do what they can to begin improving their business commons. While countries with a weak business commons may be able to compensate with strengths in the other enabling conditions, they are much less likely to realize the full benefits of the IIoT’s opportunity.

Launching the Take-off Factors

Business and government leaders also need to encourage the ‘take-off factors’ that spur on the economic impact of a new technology. Once the infrastructure for electricity started to proliferate, new inventions such as the radio and the television emerged, helping many of the world’s economies ‘take off’ toward further economic diffusion of electricity.

As the technology begins to reach a wider population, a process of standards setting (either by government or the market) begins. The battle between Tesla and Edison in the early days of electricity illustrates how technology pioneers competed to define the new era. Other industries also begin to innovate, using the core technology and generating value from it.

We can see a similar dynamic with the IIoT, as technology companies race to be IIoT leaders. This process is sped up by the fact that the IIoT can piggyback on existing telecommunications networks. Widespread mobile phone coverage and consumer use—even in the poorest countries—means that much of the world is positioned to take advantage of the IIoT in some form. It is estimated that nearly 85 percent of the IIoT is based in legacy infrastructure. Thus, consumers, businesses, and innovators can take advantage of the IIoT at relatively low cost.

Enabling the Transfer Factors

For a technology to become much more deeply ingrained in an economy, transfer factors must be developed. These factors induce wider changes in the behaviour of firms, consumers and society. The technology becomes ‘democratised.’ Knowledge of its use becomes ‘open source,; leading to widespread private-sector innovation.

The economic diffusion of the Internet in the past two decades demonstrates the impact of this process. While early Internet applications involved little more than emailing and limited file sharing, today they are the foundation for how business gets done and how many consumers conduct their daily lives. Teleconferencing replaces business travel, while the widespread use of ‘apps’ has given consumers access to seemingly unlimited amounts of information and products.

A key factor within this component is changing social norms and attitudes toward new technology. Take e-commerce as an example. Today, it generates billions in revenue, whereas ten years ago many consumers were afraid to shop online because of data privacy concerns. In many countries today, consumers still refuse to shop online because of fears of fraud. As automobiles, personal health maintenance devices, and homes become integrated into the IIoT, such concerns resonate even more with consumers.

Firms and other organizations also must adapt to the changing technological conditions, or run the risk of obsolescence. Research has shown that European firms have seen far fewer benefits from the proliferation of information and communications technology than their US counterparts in part because of their inability to redesign their organizational structures and management styles. Adapting to the IIoT will carry even greater implications for organizations’ competitiveness.

Building an Innovation Dynamo

When a technology produces self-sustaining innovation and development, it is effectively an innovation dynamo. Electricity led to electronics. Electronics led to modern computing. Modern computing combined with telecommunications led to today’s Internet and the IIoT.

The post-war development of plastics shows how a new technology not only changes business models, but works with developments in other areas to spur greater innovations. The advances in plastics, mass production, and new electrical products combined with government-sponsored infrastructure projects and home-buying programs in the post-war US led to consumer and institutional demands for lighter, cheaper, and more sophisticated products. Plastics provided the basis for countless items, from coffee makers to telephones and computers.

The innovative potential of the IIoT is only beginning to be understood. A new, grassroots source of innovation is being led by the ‘maker’ culture—a technology-based extension of do-it-yourself ethic. Many are already working to build their own personalized IIoT ecosystems in their homes through use of devices like Raspberry Pi, which allows makers to program and run their own networks, and even build their own connected robots and drones. This movement holds great promise in fostering the next generation of Internet innovators and entrepreneurs.

The emergence of an IIoT innovation dynamo can be supported through policy guidance, marketing, and investment. Technology companies as well as governments will need to expand their research and development programs to create further technological and infrastructural bases for the next generation of IIoT products. Technology clusters and tech-focused business incubators—subsidised both by large technology companies and governments—can spur the innovation process.

Galvanizing the Industrial Internet of Things

Policymakers are right to look at the IIoT as a source of economic growth and innovation. But the lessons of history tell us that without the right enabling conditions, the IIoT gamble may not pay off. What can country leaders therefore do to maximise the economic return from their IIoT investments? The specific answer will vary from country to country, but along with building the enabling conditions, policy leaders can take the following actions to increase the chances of success:

Play to Your Strengths

Does your economy have a strong high-tech industrial sector? Or is it a largely agrarian, developing nation? Such questions will help policymakers pursue appropriate investment strategies given resource constraints. It is important that they work with the grain of their economies to get the most benefit from the IIoT. For example, relatively small investments by agrarian nations in establishing sensing networks in farms and irrigation systems can have a massive payoff and capitalize on existing comparative advantages.

Create a Chain Reaction Across Industries

The IIoT has the potential to create new ecosystems cutting across traditional industry boundaries and value chains. The move to servitising products, for instance, has led to farm equipment makers teaming up with fertilizer suppliers and insurance providers. Therefore, it is important for policymakers to encourage businesses to look beyond their own industry and build new partnerships that enable the creation of new business models, and products and services.

Combat Resource Deficiencies

Many economies will come up against deficiencies in skills, capital, and technology in their efforts to realize the IIoT’s economic diffusion. Policymakers will need to consider whether to ‘make-or-buy’ these capabilities. For example, they can nurture talent within the existing workforce (‘make’), but it may be speedier to address skill gaps by tailoring immigration policy to attract skills from abroad (‘buy’). Equally, technology deficiencies may be addressed by attracting foreign direct investment and encouraging technology transfers.

Connect the Dots

To spur innovation in the IIoT, governments can draw on their powerful networks of various stakeholders (industry, academia, NGOs) to share ideas and best practices and identify mutual areas of interest for further research. Governments can also play a part in increasing collaboration and partnerships between global and large companies, SMEs, and start-ups. Facilitating and being part of such collaborations will also help ensure that policymakers design regulation in a way that does not stifle innovation.

Shorten the Investment Lag

Organizations first have to assess the potential value of a new technology before they decide to invest in it. Business and policymakers can work to shorten this time lag by promoting experimental, pilot and demonstration projects in IIoT applications. These will help raise business awareness of the benefits—and mutual growth prospects for both traditional and new service industries. Early success stories should be shared throughout the business community to spur other companies—and entrepreneurs—into action.

Policymakers are right to look at the IIoT as a source of economic growth and innovation. But there is no guarantee that the IIoT gamble will pay off. History reminds us that the diffusion of technology is not the same as its economic diffusion.

Leaders can ensure that the IIoT generates growth by understanding how economic diffusion develops over time and by building national absorptive capacity accordingly. That’s a large challenge, but considering the IIoT’s potential to add to the wealth of nations, one that should be well worth the investment.

About the Authors

Mark Purdy is a managing director and chief economist at the Accenture Institute for High Performance in London.

Ladan Davarzani is a research fellow at the Accenture Institute for High Performance in London.

[/ms-protect-content]