Talent management is built upon talent intelligence—the understanding that businesses have of the skills, expertise and qualities of their people. It is the basis of every people decision that companies make and without it, they would be reduced to just randomly hiring and promoting people. It is the fundamental foundation of modern-day talent management. And yet, the trouble with most company’s talent intelligence is that it is just not that intelligent. In this article, based on their upcoming book Talent Intelligence, the authors explain why and show what organisations can do to rectify the situation.

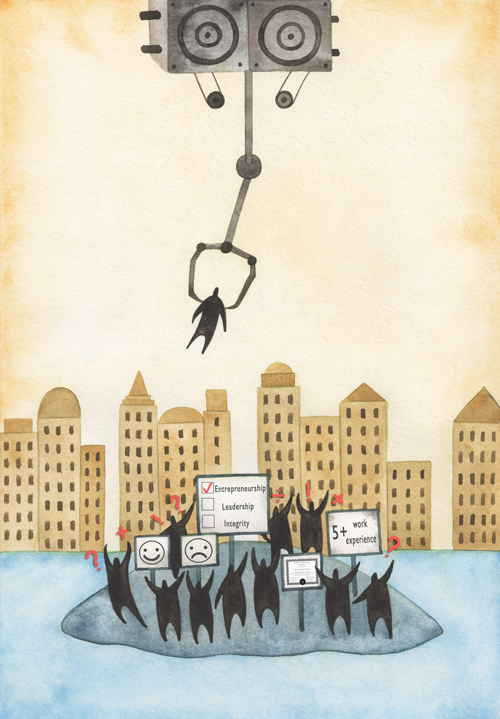

Almost 15 years ago now, McKinsey declared that there was a “war for talent” coming, and it seems they got it right.1 Globalisation and shifting population demographics are causing competition for talent to steadily and persistently rise and making it harder than ever for businesses to find the talent they need.

In the West, only 18 per cent of firms say they have enough talent in place to meet future business needs2 and more than half report that their business is already being held back by a lack of leadership talent.3 Worryingly, 75 per cent of businesses report difficulty in filling vacancies, too.4 The situation is generally not as critical in emerging markets at present, but this will change. In China, for example, the predominantly manufacturing base of its economy has largely protected it from these concerns up to now. Yet as service industries and the use of knowledge workers grow and the impact of the country’s one-child policy is felt, China too will face these challenges. The war for talent is going global.

It is not actual war, of course, but there will be casualties and there will be winners. We know that those businesses that are better at talent management and more able to find and keep the best people tend to outperform their industry’s average return to shareholders by around 22 per cent.5 In fact, making good hiring and promotion decisions can have a bigger impact on market value than creating a customer-focused environment, improving benefits or having good union relationships.6 And amidst stronger competition for talent, these performance advantages for companies that are effective at identifying and managing talent will increase.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]Realising this, alert organisations are turning to talent management for solutions, and investing in it, too. A recent US Department of Labour report predicted that over the next ten years the number of people in HR and talent management roles will grow at more than double the rate of the general workforce.

Driven forward by this investment, talent management is changing. Perhaps most notably—and arguably long overdue—it is becoming far more data-led. People data has become currency and big data and workforce analytics are the buzzwords of the moment. The idea is simple and compelling: To manage talent and make good people decisions you must know what you need, what you have and what is available. And to make this possible, new software systems have emerged that promise to help you gather, manage and use talent information more effectively than ever before. Indeed, the market for these systems is already estimated to be worth over $4 billion, and to be growing at a rate of over twenty per cent per year.

The power of talent intelligence

What these systems are trying to produce is talent intelligence: purposeful, targeted information that is capable of influencing businesses’ people decisions: from how many people are needed where and when, to whom to hire and fire. Most companies probably do not call it by this name, but they all use it nonetheless – they all have information about their people that they use to make decisions. The issue is just how sophisticated and effective they are in generating this information.

Take Google. Predictably, it is ahead of the curve when it comes to people data. Unsure of whether it was hiring the best applicants, the company developed a comprehensive database that captured information about current employees’ attitudes, behaviours, personality, biographical information and job performance. This data then enabled Google to develop an algorithm for predicting which applicants were most likely to succeed.7

Other organisations are following suit. A major UK retail bank we recently worked with linked data about the skills and behaviours of its staff with customer service feedback scores. As a result, it was better able to understand what branch managers and staff needed to do to improve customer experience and thereby sales, too.

So there is a great opportunity here, but it can only be seized if companies produce good quality intelligence. And this is where things get worrying. Over the past year, we have looked at and spoken with many of the biggest firms in the world, exploring how they create and use talent intelligence. What concerns us is that what many organisations are producing is not so much valuable talent intelligence, as just plain talent data: large quantities of information, without obvious utility. And the reason for this lies in two critical challenges that all companies face in producing their talent intelligence: knowing what data to gather and how to use it.

These, of course, are matters for any data-driven enterprise, but with talent data there are some unique issues that make them particularly challenging. And for the most part, these challenges stem from talent assessment: how organisations evaluate the quality and types of talent available to them. There is no one way of doing it. Some organisations use just the intuition of their leaders and simple interviews; others employ sophisticated online tests. But one way or another, every firm assesses talent, and however they do it they all produce potentially valuable data.

Knowing what data to gather

While much of the new talent management software is undeniably impressive, like all systems they are only as good as the data you put into them. The data current being used is predominantly things like demographics and distributions—workforce composition. This type of administrative information does have its uses, but it is limited in terms of what you can do with it, the value you can add with it.

What is surprising here is that to date talent assessment data seems largely absent from this analytical revolution. In our experience, the reason for the relative absence of assessment data from the current analytical talent management revolution lies in organisations’ relationship to it. Because for the most part, they do not understand it.

To begin with, talent assessment may seem straightforward in its basic interview-based incarnation, but it is not. In fact, it is a highly technical subject, as one would expect of what is essentially an attempt to apply science and mathematics to the issues of how to accurately measure character and predict how effective people will be in certain situations. So at a fundamental level, it is difficult to understand.

To make matters worse, the assessment market is highly fragmented and awash with vendors that either have no data on the efficacy of their tools, or who make exaggerated claims. To navigate this mess you need to be an educated consumer and that means having access to independent technical expertise. Unfortunately, the people who make decisions about talent assessment frequently have little such expertise themselves and little independent expertise available to them.8 As a result, they often either use the wrong assessment processes for their needs or use them in ways that limit their impact.

If you think we are over-stating the issue, consider this. There are some excellent vendors, services and tools on the market, but there are estimated to be over 2,000 test publishers in the US alone and only a minority of them engages in any proper validity studies.9 So only a small percentage of vendors can say with any objective authority that they know that their assessment methods genuinely work.

Moreover, even when they do have evidence of the quality of their tools this cannot be taken at face value. The reason for this lies in the worrying trend of “reporting bias.” This is the tendency for people to only publish positive results or ones that further their arguments or products. Assessment is, of course, a business and we understand that in this commercial environment vendors need to present themselves well. But recent research shows that reporting bias is far more prevalent than you might expect in an industry that professes to be grounded in science, with independent studies identifying reporting bias by some of the biggest and most well known psychometric test publishers.10

All this makes the recent actions of one of the biggest test providers in the world all the more concerning. They appear to have changed their contractual terms to prevent independent research into the validity of their tests without their approval and permission. In our view, this throws any kind of pretense about objective science straight out of the window.

So not only is talent assessment a complex and technical field, but knowing who and what to trust is not easy. It may feel at this point that it is a hopeless situation and that there is simply no easy way to determine if measures and tools actually work. But all you need to know is which questions to ask and what to look out for in the answers. We go into this issue in more depth in the book (and there is further free guidance available on the supporting website: www.measuringtalent.com). For now what is important is the point that far from being helpless, organisations have the power to change how the assessment market works and make it easier to navigate. All they need to do is to apply market forces.

For example, if they stop using vendors who do not have proper validity information, those vendors will either start producing it or disappear. Likewise, if firms simply refuse to use vendors who prohibit independent research into their tools, then these vendors will soon revert to allowing it. Far from being hopeless, the reality of the situation is that armed with just a little knowledge businesses can make a big difference.

Moreover, this change needs to happen if businesses are to change their relationship with assessment data and begin to incorporate it into their talent intelligence. And they do need to do this, because talent intelligence that does not include information about the skills, attributes and characteristics of that talent, is never going to be very intelligent.

Knowing how to use this data

Knowing what data to include in your talent analytics may be the most obvious challenge facing businesses, but just as critical is how you use the information. At present, what we tend to see is organisations collecting talent data and analysing it, but without much understanding of how best to use it. And as with knowing what data to use, some of the biggest gains to be made can be found in talent assessment data.

Organisations, then, tend to be primarily focused on whether the frontline users of talent assessment information, who are typically line managers, are using this data effectively. What they tend not to do, however, is to use this data to do more than just inform individual people decisions, such as a whether to hire a particular individual. By “something more” we mean using results of talent assessment to inform and support processes such as onboarding, succession planning and organisational learning.

For instance, one of the easiest wins with assessment data collected in recruitment processes is to use this information to help tailor onboarding and initial developmental support for new joiners. Yet research shows that only 19 per cent of firms do this.11 It is certainly common enough to hear talk of how important such issues are, but the reality is that all-too-often they are just an afterthought and so not implemented effectively, if at all.

The shame in all of this is that talent assessment data can do so much more than merely guide individual people decisions and development. And not doing more with the results is probably the single biggest missed opportunity that exists with talent assessment. With the advent of talent analytics, the situation is changing as businesses look more closely at what they can use assessment data for, but there is a lot of catching up to do.

As research for our upcoming book, we spoke to many companies—large and small—about how they used their talent assessment data and we found not a single one that was extensively, consistently and effectively using this data for more than just informing individual people decisions. And in our minds, this is just crazy. Not using talent assessment data to inform people strategy is like buying a sports car and then only ever using it to drive the kids to school. You can only ever enjoy a small margin of the value that the car can provide.

Doing this sort of thing may sound complicated, but you do not need specialist expertise—just a basic comfort with numbers and a good spreadsheet. That, and the will to do it. One of the key things here is to look for how connected the different types of talent data you collect are both with each other and with other sorts of information. For example, knowing the average competency ratings of new hires can be useful. Yet if you also know the performance scores of new hires one year after they have joined, you can see which competencies are most predictive of initial success. If you know who is still employed three years later, you can work out which factors are most predictive of retention. And if you know who is later promoted, it can provide insight into the types of talent valued in your business and the qualities predictive of longer-term success.

A few years ago, a large global business in the energy sector asked us to help it establish assessment processes to support three key people decisions: recruitment, promotion, and the identification of high-potentials. The processes created were not complex, but we were able to use this simple data to achieve lasting, significant changes in their people strategy:

• We looked at the competency ratings of new hires in each division to check whether some divisions were attracting stronger candidates and whether the qualities of new hires were aligned with each unit’s business objectives. As a result, all three divisions were able to make improvements to their attraction and hiring activities.

• We compared the average competency ratings of new recruits with those of current employees. We found that the new hires had an uncannily similar pattern of strengths and weaknesses to the current employees. This kick-started a debate in the business about whether it was “just employing clones,” which in turn led to changes in hiring practices.

• We looked at the qualities that distinguished those identified as high-potentials and those being promoted. We found that the people labelled as high-potential were generally better at performing well, being outgoing and showing entrepreneurial spirit. In a business trying to adopt a faster-paced and edgier approach, this was a good finding. But when we looked at the qualities most likely to lead to promotion we found that the people being chosen were those who performed well and were viewed as team players. For all the encouragement the business was trying to give people with the qualities it thought it wanted, the people actually being promoted were different. As a result of these findings, new criteria for promotion were implemented.

• Finally, we looked at the average competency profiles of the various groups measured and fed the findings into the learning and leadership development functions. As a result, specific development programs were created to address key competency weaknesses in particular groups of employees. The measurement data thus enabled better targeting of learning investment.These were all simple steps, accomplished with simple data and without resorting to expensive systems. But they led to powerful findings that ultimately helped the business deliver its growth strategy. And this is the key, critical difference between plain talent data and real talent intelligence: intelligence is information that makes a difference, that adds value, that helps you to improve the bottom line of your business. Everything else is just data.

Moving forwards

All the headlines in talent management in recent years have gone to succession plans and talent pools, to managing talent ‘on demand’ and making talent management streamlined and simple. And all of this is good and desirable. Yet none of it stands a chance of making any real difference unless it is built upon good talent intelligence.

Organisations have largely escaped being penalised for having poor or unreliable talent intelligence to date because every other firm has had the same problem. But things are changing. Business, like every other aspect of modern society, is moving ever farther forwards into an age of information and data analytics. As it does so, business leaders are expecting more from their talent data and this is driving improvements and innovation in how firms gather and leverage this information. So stand still for much longer, and you will be left behind, disadvantaged by the poor nature of your talent intelligence. It is time to get this critical, but too often overlooked foundation of talent management right.

About the Authors

Nik Kinleyis a London-based independent consultant who has specialised in the fields of talent measurement and behaviour change for over twenty years, operating in both the private and public sectors and across a range of industries. He was formerly the Global Head of Assessment for the BP Group, Head of Learning for Barclays GRBF, and a senior consultant with YSC, the leading European assessment firm.

Shlomo Ben-Hur is an organisational psychologist and professor of leadership and organisational behaviour at the IMD business school in Switzerland. He has more than 20 years of corporate experience in senior executive positions including Vice President of Leadership Development and Learning for the BP Group, and Chief Learning Officer for DaimlerChrysler Services.

References

1. Chambers, E.G., Foulton, M., Handfield-Jones, H., Hankin, S.M., & Michaels III, E.G. (1998). The War forTalent. The McKinsey Quarterly. 3, 44-57.

2. Boatman, J. & Wellins, R.S. (2011). Global Leadership Forecast. Pittsburgh, PA: Development Dimensions International, Inc.

3. Bersin & Associates (2011). TalentWatch Q1 2011 – Global growth creates new war for talent. Oakland, CA: Bersin & Associates.

4. CIPD. (2011). Resourcing and Talent Planning—Annual Survey Report. London: CIPD.

SHRM. (2011). The Ongoing Impact of the Recession—Recruiting and Skill Gap. SHRM.

5. Axelrod, E.L., Handfield-Jones, H., & Welsh, T. (2001). The War for Talent, Part Two. The McKinsey Quarterly. 2, 9-11.

Huselid, M.A (1995). The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Turnover, Productivity, and Corporate Financial Performance. Academy of Management Journal. 38(3), 635-872.

Combs, J., Liu, Y., Hall, A. & Ketchen, D. (2006). How Much Do High-Performance Work Practices Matter? A Meta-Analysis of Their Effects on Organizational Performance. Personnel Psychology. 59, 501-528.

6. Watson Wyatt (2002) Linking Human Capital and Shareholder Value: Human Capital Index. Fourth European Survey Report. London: Watson Wyatt Worldwide.

7. Hansell, S. (2007) Google Answer to Filling Jobs is an Algorithm. New York Times, January 3.

8. Terpstra, D.E. (1996). The Search for Effective Methods. HR Focus. 73, 16-17.

Terpstra, D.E. & Rozell, E.J. (1997). Attitudes of Practitioners in Human Resource Management toward Information from Academic Research. Psychological Reports. 80, 403-412.

9. Hogan, R. (2005). In Defense of Personality Measurement: New Wine for Old Whiners. Human Performance. 18(4), 331-341.

10. McDaniel, M.A., Rothstein, H.R., & Whetzel, D.L. (2006). Publication Bias: A Case Study of Four Test Vendors. Personnel Psychology. 59, 927-953.

11. MacKinnon, R.A. (2010) Assessment & Talent Management Survey. London: TalentQ.