The recent economic crisis has created waves of turbulence that have rocked and even sunk many UK organisations. This article looks at the effects of this turbulence on both organisations and, more specifically, on the managers who work within them. Les Worrall and Cary Cooper reveal that cost reduction-driven organisational change has ripped through businesses and that the impact of this change has worsened the quality of working life of many managers. More importantly, the authors identify that the gap between the perceptions of those at the top of organisations has widened from those at lower levels, providing an analysis that raises major concerns about how well UK organisations are being managed.

Introduction

Since 2007, the UK economy has suffered the deepest, most protracted recession and period of no/low growth since the 1930s. In his 2007 budget statement the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, commented ‘And we will never return to the old boom and bust’ – never has a politician got it so wrong. Within a year, the UK’s biggest boom became its biggest bust. As the credit crunch was superseded by the euro crisis, the UK economy has suffered a period of protracted turmoil. But, how has this turmoil affected organisations? And, more important, how has it affected mana-gers’ wellbeing?

Since 1997, we have been conducting research to assess how well the managerial assets of the UK are being managed and how the quality of managers’ working lives is changing. Luckily, we ran a survey in 2007 – just before the credit crunch. We decided to run another survey in 2012 to measure how the quality of managers’ working lives had changed over the intervening, tumultuous years. Consequently, we have been able to explore how successive waves of turbulence have impacted upon a wide range of measures such as the hours managers work, on managers’ physical and psychological health and on measures such as job satisfaction, employee engagement and sense of job security. While we were not surprised by our findings, we were disturbed by them and particularly by the scale, pace and impact of the changes we unearthed.

Cost Reduction and Sweating Managerial Assets – The Prime Driver of Change

The percentage of managers affected by radical organisational change increased markedly from 2007 as organisations sought to reduce costs by reducing headcount, by intensifying their use of managerial labour and by creating an environment in which managers felt it necessary to work harder, faster and longer. In 2012, over 82 per cent of managers cited cost reduction as the prime driver of change compared to 60 per cent in 2007. As a result of the pace, scale and intensity of change – and also because managers had often experienced overlapping waves of change – managers’ views of the effect of organisational change were overwhelmingly negative: 68 per cent reported a lower sense of job security; 70 per cent reported reduced morale; 64 per cent reported reduced motivation; and, 53 per cent claimed that organisational change had reduced their sense of wellbeing at work. All these measures had deteriorated from 2007.

Our data allowed us to assess change for different levels of management and we soon became concerned about the disparity in perceptions between those at the apex of the organisational pyramid and those at its base. Far more important, we found that this gap had widened on many of our measures. For example, while 37 per cent of directors felt that change had decreased morale, this increased to 82 per cent for junior managers. The equivalent figures for 2007 were 34 per cent for directors and 63 per cent for junior managers. While the score for directors had deteriorated slightly, the deterioration for junior managers was far more marked. In all the surveys we have conducted since 1997, we have found a disparity between the views of directors and all other managers. In 2012, we were disconcerted to find that the difference between directors and all other grades of manager had widened almost all our measures. The perceptions gap between those at the apex of the organisational pyramid and those at its base had widened noticeably and we are concerned that the impact of change has not been experienced more evenly across organisations.

The Dubious Rhetoric of Organisational Change

Organisational change is usually ‘sold’ to employees using the rhetoric of increased flexibility, employee participation and productivity. Our research reveals that only a minority of employees was convinced that change had had these effects. It did reveal that directors were far more likely to have convinced themselves that organisational change had delivered positive outcomes. For example, directors were more than twice as likely as junior managers to think that change had led to increased productivity, faster decision making, increased employee engagement and increased flexibility. Junior managers were more than twice as likely as directors to think that change had caused the organisation to lose key skills and experience. All these gap measures had widened since 2007. It is abundantly clear that the effect of organisational change had, as in all our previous studies, not been seen positively – except by directors. Organisational change – especially if you were a junior manager – was felt to have had negative effects on your morale, loyalty, motivation and psychological wellbeing. Consequently, we believe that directors had become even more distant from the day-to-day reality of the organisations that they were attempting to lead.

Working Harder, Faster and Longer

In 2012, managers overwhelmingly felt that organisational change had increased the pressure on them to work harder, (78 per cent), increased the volume of work they had to do (76 per cent), increase the pace of work (66 per cent) and increased the pressure on them to work longer hours (61 per cent). Interestingly, junior managers were more than twice as likely as directors to feel that they now had less control over how they did their jobs. The main effect of organisational change had been to force workers – many of whom now felt less secure in their jobs – to intensify and extensify their work effort. The prime effect of cost reduction-driven organisational change had been to increase the pressure to work harder, faster and longer with the erosion of managers’ control over how they do their jobs. The rhetoric of employee engagement and empowerment and the reality of managers’ working lives seem to be two completely different things.

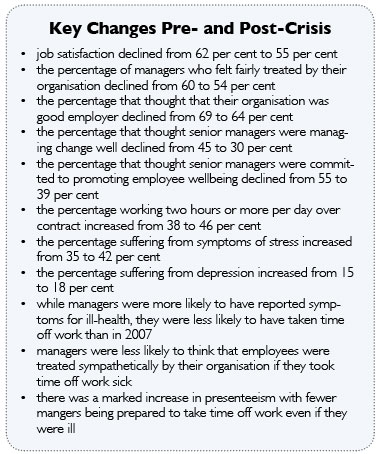

Work-life balance has effects both inside and outside the workplace. Inside the workplace working too many hours is a driver of stress and physical and psychological ill-health. Outside the workplace it has a profound impact on individuals and their families. These effects are significantly enhanced if managers feel that they have no control over the hours they work. By 2012, there was a marked increase in the percentage of managers who worked two hours or more per day over their contract hours. In 2007, 38 per cent of managers worked two hours or more per day over contract but by 2012 this had increased to 46 per cent. Worryingly, over 50 per cent of managers said that working long hours had a negative effect on their stress levels and on their psychological and physical health. For some groups of managers, the effects were more extreme. For managers who worked three hours or more per day over contract and were only doing so because of the pressure of work, 78 per cent felt that the hours they worked had had a negative impact on their stress levels, 76 per cent felt that it had had a negative effect on their physical health and 70 per cent felt it had had a negative effect on their psychological health. Given these adverse health and wellbeing effects, it is disturbing that the percentage of managers who now feel they have to work very long hours over contract has increased since 2007.

The Evolving Picture of Managers’ Health: Changes from 2007 to 2012

An important element of our research is monitoring change in managers’ physical and psychological health. In both surveys, we obtained managers’ views about their physical and psychological health using two sets of questions. The first set asked managers about their experience of common physical manifestations of ill-health. The second set referred more to aspects of psychological wellbeing – some of which were crucially important as they affected managers’ behaviour at work and, in particular, their ability to do their jobs effectively (for example, managers were asked if they had suffered from feeling unable to cope, anxiety and from having difficulty in concentrating).

While the incidence of ill-health in 2012 is important, what is more important is how the incidence of ill-health has changed over time. Managers reported worse scores on twelve of the thirteen measures of physical ill-health we examined. The percentage of managers that experienced symptoms of stress showed the greatest increase – from 35 per cent to 42 per cent. We regard a seven percentage point increase in our stress measure as an issue of some concern. The percentage of managers experiencing symptoms of depression increased from 15 per cent to 18 per cent. The percentage of managers who had suffered from the symptoms of stress and depression varied sharply in the organisational hierarchy. Directors were the least likely to report stress (32 per cent) and depression (13 per cent) while junior managers were the most likely to report stress (49 per cent) and depression (28 per cent).

Fifteen of our seventeen measures of psychological ill-health worsened. Of particular concern was the decline in the measures that directly affected managers’ ability to do their jobs effectively such as constant tiredness, difficulty in making decisions and having difficulty in concentrating. For example, the percentage of managers that had difficulty concentrating increased from 37 per cent to 45 per cent with constant tiredness and insomnia/sleep loss remaining persistently high and deteriorating from their 2007 levels.

An analysis of absence and ill-health revealed an important finding: while the proportion of managers experiencing symptoms had increased, their absence levels and their willingness to take time off work when ill had decreased. Our concern here is that ‘presenteeism’ and the tendency to ‘soldier on’ even when unwell had become more prevalent indicating managers’ concerns that taking time off may undermine their future job security at a time when their sense of job insecurity had increased. Managers also reported that their organisations had become less tolerant of absence and that attitudes to those taking absence had hardened.

Directors were least likely to report having experienced symptoms of ill-health on all of our measures and junior managers were the least likely. On most measures, the differences between directors and junior managers were wide and had widened: for example, while 18 per cent of directors had had feelings of being unable to cope, this increased to 42 per cent of junior managers; and the percentage of junior managers reporting sleep loss/insomnia increased from 57 per cent to 70 per cent.

The Managerial Implications of our Findings

We are not against organisation change: organisations cannot be preserved in aspic or they will ossify, become less competitive and, ultimately, die. What we are against is poorly managed organisational change and it is disconcerting to note that our respondents’ views of how well change was being managed by top management had deteriorated. In 2007, 45 per cent thought that top management in their organisation was managing change well but this declined to 30 per cent in 2012. What we ask is that, when planning change, top management think more deeply about the effects of change on employees’ wellbeing and on the volume and pace of work that those affected by change will have to cope with. It is clear that too many directors have too little understanding of the wider organisational costs and consequences of cost reduction, of redundancy, of delayering, of work intensification and of the erosion of terms and conditions.

A comparison of 2007 and 2012 reveals that many organisations have taken a step backward on measures that are generally seen as desirable and indicative of good management practice: respondents felt less fairly treated; levels of mutual trust declined; managers’ sense of empowerment declined; and, top managers were seen as less committed to promoting wellbeing and less favourably as effective managers of change. It is not surprising that job satisfaction declined.

The impact of the post 2007 recession on the UK economy has been profound and it has sent shock waves through many organisations. While we accept that responding to these shocks has been difficult for many top managers, we feel that they need to become far more adept at managing change if their organisations are to grow and prosper in the future. While cost reduction might be needed, it always has huge costs of its own and, in making their restructuring decisions, top managers need to factor in the costs of lost productivity through employee ill-health, workforce alienation and losing the key skills that their organisations will need if they are to grow in the future. Top managers should be less self-deluding about what they can realistically achieve without causing long term, irreparable damage to their organisations, and they should certainly do all they can to avoid serial waves of continuous change that only serve to disorientate and demotivate the workforce and ultimately undermine the cultural fabric of the organisation.

Our research is conducted in partnership with the Chartered Management Institute. The 2007 and 2012 surveys were both sponsored by Simplyhealth.

About the Authors

Professor Les Worrall FCMI, is Professor of Strategic Analysis in the Faculty of Business, Environment and Society at Coventry University. He is a Fellow of the Chartered Management Institute. His research interests include organisational analysis and changing patterns of work. He has conducted consultancy and applied management research for several blue chip companies.

Professor Cary Cooper CBE CCMI is Distinguished Professor of Organisational Psychology and Health at Lancaster University Management School. He is the author/editor of over 120 books on occupational stress, women at work and industrial and organisational psychology, has written over 400 scholarly articles for academic journals, and is a frequent contributor to national newspapers, TV and radio.

References

• Worrall, L. and Cooper C.L. (2007) The quality of working life 2007: Managers’ health, motivation and productivity. The CMI/Simplyhealth Quality of Working Life Survey. London: CMI

• Worrall, L. and Cooper C. L. (2012) The quality of working life 2012: Managers’ wellbeing, motivation and productivity. The CMI/Simplyhealth Quality of Working Life Survey. London: CMI