Today’s companies are global in nature and for many, this translates into a dynamic environment for designing their Supply Chains, in order to optimise the overall processes or relocating the industrial operations abroad (Offshoring) or re-thinking about how to bring them “back home” (Reshoring).

Today’s companies are global in nature and as such, they’re exposed to uncertainty and volatility in marketplaces, where the only paradoxical certainty is represented by the unavoidable and continuous mutation of the conditions of the context they operate in. For many companies, this translates into a dynamic environment for designing their supply chain. More than 20 years ago, General Motors began moving their facilities into the Far East, kicking off a trend to include offshore locations as part of their global supply chain. This helped elevate the supply chain into a key-role and function to help develop the company business. More recently, there are a number of factors that have led some to claim that there is a groundswell of movement by companies to shutter Asia-based offshore operations in favour of re-creating operations in Western headquarters locations. This alleged trend and variations have been referred to as “reshoring”.

Among the different factors which in different manners contribute to favour the phenomenon of the relocation of industries in the West countries, themes concerning energy and labour cost are crucial.

For example, related to energy cost, referring to 2011, the natural gas processing in the USA has increased by 24% (compared to 2006 – The White House Report, 2012).1 North Americans have managed to make processing far cheaper than in other developed countries such as China (+16%), France (+28%), Germany (+29%).2,3 Meanwhile, the United States became less dependent from volatile geopolitical dynamics.

On the other hand, a considerable increase of productivity has made labour cost in the US particularly attractive, especially because together with the US labour cost, salaries in China have increased too. For instance, referring to the US-scenario only, labour cost decreased about 9%, 6% & 4% on the related consumer appliances, machinery and furniture’s cost structures. This meaningful data emerges from a study leaded by the authors, analysing a set of US-industries’ cost structures between 1999 and 2012.

Therefore, changes in cost structure’s components might lead to reduce the US gap with China in some cases, making the “tipping point” closer (defining the “tipping point” as the overall cost structure difference limit to consider for a localisation change – this study relate to US and China), assumed it as the estimated percentage of 16%, over this balance point every consideration in terms of re-location will be allegedly considered more and more crucial.4

[ms-protect-content id=”5662″]

The authors of the report intend to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the current dynamics to help with a broader understanding of those dynamics in order to define, to contextualise, and to analyse the “reshoring” movement from a supply chain perspective. As previously introduced, the authors produced a research that led to the creation/analysis of a broad dataset of several industry cost structures’ development across a nearly 15-year period, from 1999 through 2012, taking the American market as the final reference point, and considering the Chinese baseline as a production reference.

Differently from the past, the study has not been conducted on surveys and case-studies’ gain, but the authors built up a quantitative dataset model which should be able to describe different industry trends, related to the developments in their cost structure. Hence, reshoring has been analysed under a different perspective, monitoring trends for every cost structure component, related to a broad set of industries (Consumer Appliances, Consumer Electronics, Machinery, Furniture, Chemicals, Plastics, Apparel and Fashion).

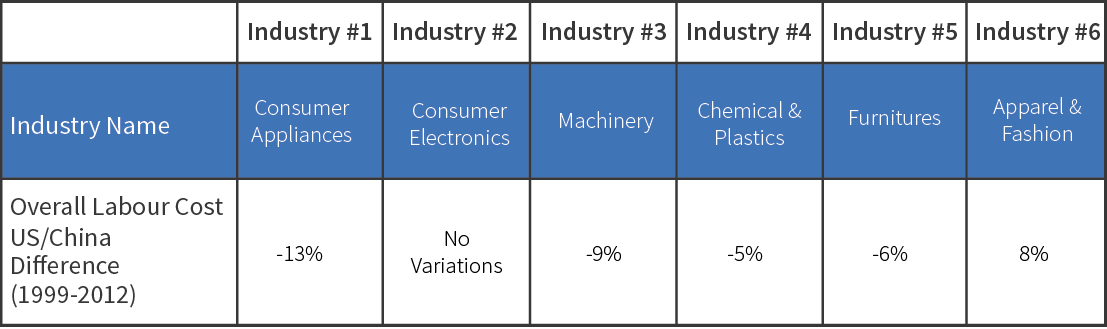

Yet, there is much more than this. American selected industries’ cost structures have been compared to the Chinese related ones, in order to underline how every gap’s trend developed in the 1999-2012’s timespan. These insights were meaningful: for example, related to American-Chinese gap in labour costs, it decreased about 13% for consumer appliances, while it will drop by 9% for machinery. At the same time, apparel and fashion’s differential has been rising up to 8% more.

In order to have a complete idea of the Labour Cost Analysis, authors provided summary of results, as explained in the Table 1, as reported.

Table 1: Labour Cost: US/China Analysis Results: Summary of Changes

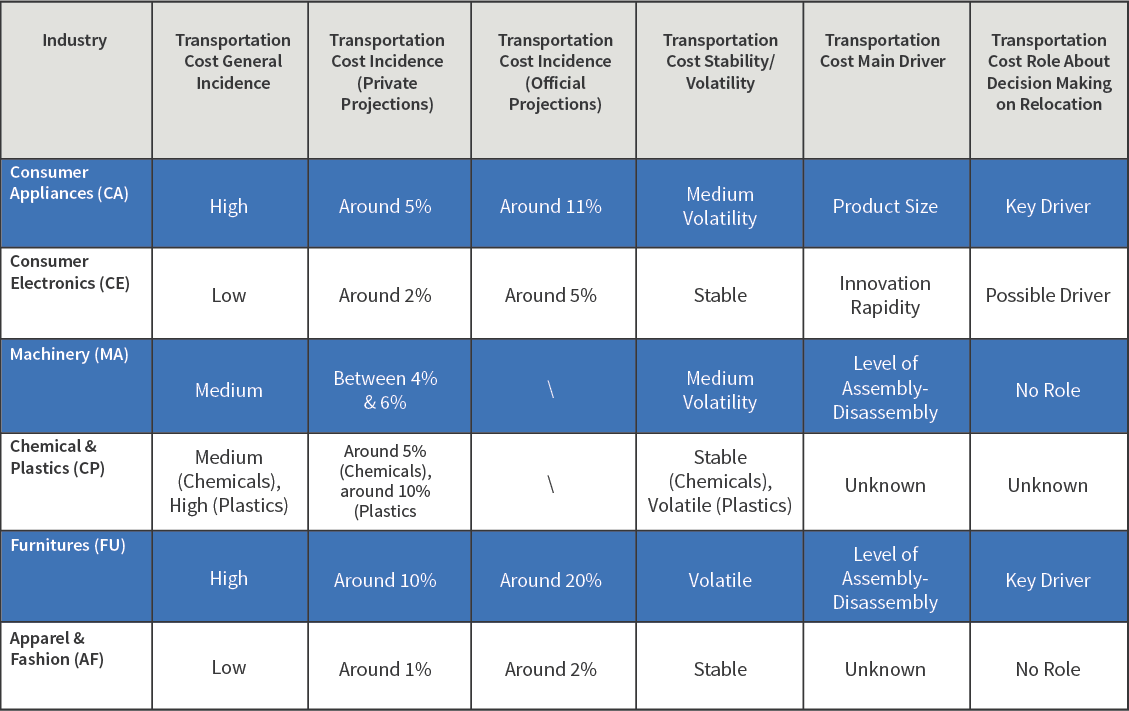

This is not strange at all: it might be assumed as one of the reasons to explain a broad set of reshoring case-studies about consumer appliances and machinery, and very few related to the apparel and fashion industry. In addition to that, the effects of the unpredictability of the price of crude oil contributes to a fluctuation in the structure of some industry costs, especially where transportation cost assumes a key role in the business, due to specific aspects of some of the involved industries (i.e. Consumer Appliances and Furniture).

In Table 2, Transportation Cost Analysis results summary have been reported. As clear, industry by industry, Transportation Cost’s incidence has been analysed in terms of share in the related business cost structure and considering other qualitative aspects emerging from the specific industry studies (i.e. key cost driver related to each industry).

Table 2: Transportation Cost Analysis Results: Summary

The entire study of the data by creating a descriptive model (and potentially, “predictive”) let the authors to define a precise reference framework and take a clearer and stronger position compared to the existing studies. They have also been the first to prove a strong relationship between cost structures and relocation for every sector. Based on the analysis of the industry cost structure drivers as well as on an interpretation of the dynamics, the authors offer suggestions from a quantitative perspective.

Several non-quantitative aspects have been not included in the model yet, so further developments and integrations are more than possible. For example, it might be interesting how to relate issues regarding intellectual property’s management and relocation strategies. Other interesting developments might concern how the sector’s rapidity can push the related industry’s players closer to the costumers. For example, this last aspect represents an actual dynamic operating into the consumer electronic industry: innovation’s speed cannot allow long transportation time without assuming it as a concrete risk in the progress of bringing the player closer to the costumer.

Therefore, on the one hand, the authors have centred their assumptions on data extrapolation from the dataset, but on the other hand they related the trends to the case-studies and to reality. This analysis leads the author to define conceptual limits of the reshoring phenomenon in a wider framework, bringing to a more complex scenario of the Supply Chain Design’s panorama.

As said, analysis was conducted on data considering several different industries, with the following conclusions and final remarks:

Reshoring is not a trend in the sense of a meaningful representation of industry practitioners behaviour in re-locating production operations back to original locations. The data does not indicate that this is occurring across all or even many industries. At this point in time, Reshoring appears more of a descriptor of some companies that have relocated operations back to home locations but this is more a function of the industry’s dynamics and its related cost structures.

Reshoring is distinct from Offshoring and there is no evidence suggesting a connection between the two within industry. Although the Far East delocalisation has been often superficially described as the Reshoring’s opposite, no Far East plant has been closed due to come back to the West .

Reshoring represents a Supply Chain Design matter, related to the best productive-logistic global configuration’s design in order to serve the corporate business strategy. Although qualitative features have not been exhaustively reviewed in this paper and research, reshoring represents a concise supply chain design decision in the whole company strategy, not a simple trend-back.

Reshoring seems to assume a role in a sort of world regionalisation, as introduced by several studies and recent surveys (i.e. The Hackett Group-Jansen et al., 2012,5 The Standard Chartered Global Research – Jha et al., 2015,6 and AlixPartners 2016 Survey)7.

Indeed, “Reg-shoring” (Regionalisation) makes sense once assumed the view as wider, considering horizontal supply chains, the resilience and other factors to be explored as related evidences. Specifically, there is more evidence that would suggest that firms are locating production operations in multiple regions in order to serve those regions, rather than locating production operations in single locations based on low-labour costs or home headquarter locations.

Further research is definitely necessary. For example, it would be productive to consider the role of related industry innovation and financing, especially as factors that may affect and/or influence more of a regional approach to location selection.

Yet, relationship to industry level of innovation or aspects related to finance’s role are only a couple among a broad set of suggestions emerging from the study, as said, representing only a starting point to further explorations on the subject.

Therefore, due to all the explained reasons, Reshoring is not a trend.

It might be assumed as a strategic option to pick whenever the related industry cost structure’s conditions push to a different business model, making production closer to consumption. Maybe 100% reshored, maybe nearshored. Definitely to a “local-to-local” approach.[/ms-protect-content]

About the Author

Francesco Stefanelli gained his Ph.D in Supply Chain Strategy at the University of Ancona, visiting the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has been working as Manager in the Management Consulting Industry and nearby Global Companies in the Operations and Supply Chain functions. His has worked in more than 15 industries across 55 projects of different nature and complexity in 10 different countries all around the World.

Francesco Stefanelli gained his Ph.D in Supply Chain Strategy at the University of Ancona, visiting the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He has been working as Manager in the Management Consulting Industry and nearby Global Companies in the Operations and Supply Chain functions. His has worked in more than 15 industries across 55 projects of different nature and complexity in 10 different countries all around the World.

References

1. The White House Report (2012). “Investing in America: building an Economy that lasts”.

2. Blanchard D. (2013). “Reshoring Manufacturing’s”. The Industry Week-10.

3. Sirkin H., Zinser M., Hohner D. (2011). “Made in America, again”. The Boston Consulting Group.

4. Janssen M., Dorr E., Sievers D. P. (2012). “Reshoring global manufacturing: myths and realities”. The Hackett Group Enterprise Strategy Report.

5. Janssen M., Dorr E., Sievers D. P. (2012). “Reshoring global manufacturing: myths and realities”. The Hackett Group Enterprise Strategy Report.

6. Jha M., Amerasinghe S., Calverley J. (2015). “Special Report – Global Supply Chains: New Directions”. Standard Chartered Global Research-2015.

7. AlixPartners Survey (2017), “Homeward bound: nearshoring continues, labor becomes a limiting factor, and automation takes root”.