In Creative Strategy: A Guide for Innovation, William Duggan shows how the human mind creates solutions to new problems and then translates that mental method into a series of formal steps that an individual or group can use for innovation of any kind. The mental method is ‘strategic intuition’, which Duggan’s previous book Strategic Intuition explains in detail. Below, an excerpt from Creative Strategy discusses a set of steps that can be used to apply strategic intuition, outlining a formal method for innovation.

Strategic Intuition

To start, we must go back to three key milestones in the recent history of the science of the mind. The first came in 1981, when Roger Sperry won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the two sides of the brain. Sperry concluded from his experiments that one side of the brain is rational and analytical but lacks imagination and that the other side of the brain is creative and intuitive but irrational.

Unfortunately, our second key milestone overturned this dual model of the mind. In the early 1990s, Seiji Ogawa figured out how to use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to show how ideas emerge in the human brain. Ogawa has been on the short list for the Nobel Prize for some years now. His work let scientists see which parts of the brain different mental tasks actually use. From Ogawa’s first MRIs, it was immediately clear that there are not two kinds of thinking that operate on two different sides of the brain.

Although Ogawa’s work overturned Sperry’s dual model, it took science another decade to arrive at a new model to replace it. Our third key milestone came in 2000, when Eric Kandel won the same Nobel Prize as Sperry for his work on this new model. Kandel called it “learning-and-memory,” where the whole brain takes in and stores information through sensation and analysis and retrieves it through conscious and unconscious search and combination. In this model, analysis and intuition are not two different kinds of thought, in two different locations, but rather two key inputs into a single mode of thought that operates throughout the brain. Some thought has more analysis, some has more intuition, but all thought requires both.

Learning-and-memory gives a very different picture of how innovation works. Let’s start with analysis. We commonly say analysis is a rational or logical process, but it can never be purely so except in mathematics. We can break down the number 20 into factors of 10 and 2 or 5 and 4. Mathematics is a closed system, so we know we are right. It’s logical. But now let’s analyze something that is not pure math: the performance of your company or organization over the past decade. What do I include in my analysis, and what do I leave out? For example, the weather: Should we gather data on temperature and plot that against a measure of unit performance? If I say yes and you say no, which one of us is right? If we disagree, we argue using “logical” arguments, but that does not mean our educated guesses came to us through logic. And our arguments are not purely logical at all, of course, regardless of what we might claim. So how did our educated guesses arrive? Why did I say we should collect weather data, and why did you say we should not? If not by logic, then by what?

Learning-and-memory gives us a clue. You and I have different information in our memories, which we acquired by learning different things. Although we face the same question—the performance of your company or organization over the past decade—we draw on different memories to analyze it. And we do so in two distinct ways: “expert intuition” and “strategic intuition.” These are the two main mechanisms the brain uses to apply memories to current and future situations.

We now know that expert intuition is the rapid recall and application of thoughts and actions from direct experience in similar situations. So a nurse can walk across the emergency room floor, glance at a child, and rush over to save the child’s life. How did she do it? She noticed something she had seen before—in the child’s eyes, how the child was sitting, and so forth.

We develop and use expert intuition every day, in all kinds of skills and tasks. Most professional training increases expert intuition. But expert intuition can be the enemy of innovation. We see a new situation and quickly see what’s familiar within it and act accordingly. But if the situation is different enough, we’ve just made a big mistake. Expert intuition cannot solve a strategic or creative problem, which by definition is a new situation. What if our nurse’s emergency room is dirty, crowded, and losing money—and she’s never experienced that before? She can’t just walk across the floor and recall the answer from her past experience. Expert intuition won’t work.

She needs strategic intuition instead. This is a particular form of learning-and-memory that has strong roots both in the science of how ideas form in the mind and in empirical cases of successful strategy. The brain selects a set of elements from memory, combines them in a new way, and projects that new combination into the future as a course of action to follow. The past elements come from both direct experience and the experience of others that you learned through reading, hearing, or seeing.

Once we understand how learning-and-memory creates new ideas, we can go back to some classics of strategy and see elements of strategic intuition within them, in particular Sun Zi’s Art of War and On War by Carl von Clausewitz. Modern brain research shows that Sun Zi’s Dao philosophy promotes a state of mind conducive to flashes of insight. And Clausewitz gives four keys to strategic intuition that produce innovation in any field of endeavor: examples from history, presence of mind, coup d’oeil, and resolution.

These four steps of Clausewitz offer a useful bridge from the science of strategic intuition to the method of creative strategy. They help us see how you can make conscious use of your unconscious learning-and-memory, at least in part. In the first step, “examples from history,” you learn, retain, and recall in memory the elements of what others did to succeed in a previous situation.

The second step, “presence of mind,” has a direct parallel in the Dao philosophy of Sun Zi and Asian martial arts. You must free your mind of all expectations. You “expect the unexpected,” as Clausewitz puts it. This is actually very difficult to do. The two biggest obstacles to presence of mind are excessive focus and negative emotions.

The third step, coup d’oeil—or “glance” in French—is the term Clausewitz uses for a flash of insight. Modern brain science shows how presence of mind fosters flashes of insight. When your mind is clear, selected examples from your memory combine in a new way to show you what course of action to take. The result is a strategy, but not a complete one—just key elements that show you the way.

Last comes “resolution,” that is, resolve, determination, will. The flash of insight sparks a conviction that this is the right path despite the obstacles and resistance you will face, especially from others around you who did not have the idea. Of course, it is hard to distinguish good resolution for a good coup d’oeil from stubborn persistence for a bad idea. But examples from history offer help. If these examples that made up the coup d’oeil are solid and in sum cover the new situation, then it’s likely a good idea.

We can now look at how innovation really works. Let’s go back to the question of your company’s performance over the past decade. You look at the situation and come up with a set of measures and data that you compile from memory of similar situations. If these parallels come quickly, from only your own direct experience, that’s expert intuition. If it takes more time, and you draw from situations you know about but are not from your direct experience, that’s strategic intuition. In practice you typically draw from both and don’t sort out which is which. But the strength of your resolution—how hard you argue your case and how firmly you believe the idea will work— depends on how strong those parallels seem to you, regardless of whether you are conscious of them and able to explain them to others.

It is unlikely that anyone on earth has had enough of the right direct experience to understand every aspect of your company’s performance over the past decade solely through expert intuition. Situations where expert intuition alone won’t suffice are “strategic,” so you need strategic intuition to find a solution. If the situation is within your direct experience, that’s a “tactical” situation, and expert intuition can work. Innovation as strategic intuition is thus the search for the right combination of parallels within and beyond your own experience to apply to a new situation.

In the same way that learning-and-memory applies to understanding your situation, it helps you decide what action to take in the face of the situation. What course of action your company should pursue in the future is clearly a strategic question, where no one person has enough direct experience to give a good answer solely from that source. Expert intuition won’t work. You need strategic intuition instead.

Creative Strategy

In ordinary practice, innovators are seldom conscious of the precise examples from history that make up their flashes of insight. But in team situations, it helps greatly to make your examples explicit. In modern organizations, we do. The solution is to convert the four elements of Clausewitz into a more formal method of innovation for teams. The result is “creative strategy,” where you apply strategic intuition in a systematic way to find a creative solution to a strategic problem.

The method of creative strategy follows three phases that draw from three diverse sources beyond those I’ve cited so far: “rapid appraisal” in international economic development, a “what-works scan” from social policy research, and “creative combination” from General Electric’s corporate university in the late 1990s. Together, these three sources give us a team method that matches what a single brain does in the flash of insight that comes from strategic intuition.

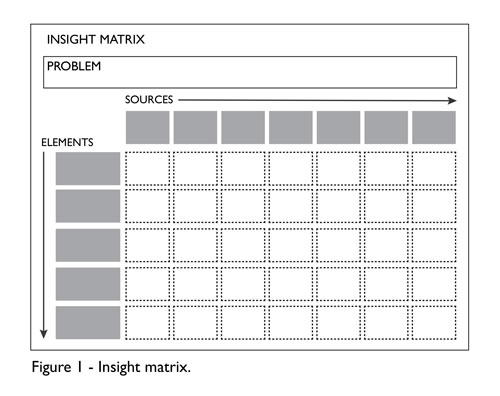

All three phases—rapid appraisal, the what-works scan, and creative combination—use an “insight matrix” to organize examples from history that the rapid appraisal and what-works scan discover. At the top of the matrix, your team writes down your current understanding of the situation or problem, always as a provisional draft, because the problem might change as you proceed to solve it.

Once you have a preliminary problem statement, analysis comes next: you break down the problem into smaller pieces. You list these in rows, also in draft, because they too might change as you proceed. We call these problem pieces “elements,” as in chemistry, where different chemical compounds are made up of elements in various combinations. After all, the term analysis itself comes from chemistry, where you break down a compound into its elements.

These first two parts of creative strategy—stating the problem and its elements—need not take much time, but you must do them well and with the right people. This is where rapid appraisal comes in. It’s a set of iterative interview and research techniques that gain insight into a complex problem. The interviewees must include the leaders who will ultimately decide what innovation to pursue in addition to the leaders who will take the lead in pursuing it.

Next you move to the second phase of creative strategy: the what- works scan. You ask the most important question you can ever ask to solve any problem of any kind: Has anyone else in the world ever made progress on any piece of this puzzle? Across the top of the matrix, as columns, you list sources to search for answers to this question. Again your list is in draft form, because you might add or delete sources as you proceed. Once you have a few sources on the list, the team starts a treasure hunt: the what- works scan. You search the sources for “examples from history” that might apply to each element on the list of problem pieces.

We will call examples from history “precedents.” In the what-works scan, every source has several potential precedents that might or might not fit your problem. You never use the whole source as your precedent. For example, if “branding” is a problem element, Starbucks might be a source for you. You might say you want to brand “like Starbucks,” but you’re not going to imitate everything Starbucks does to build its brand.

Finding relevant precedents is not easy, because outside of physical science we lack statistical “proof ” that one set of actions works best to yield a particular effect. Because of this, the what-works scan has its own specialized methods and techniques to arrive at a set of precedents that fit the problem at hand. This scan is a key difference between creative strategy and most other innovation methods, which spend most of their time and effort on research about the problem. In contrast, creative strategy comes after the key leaders in charge of the problem have already done their homework in that regard by whatever method they think best. Once they understand the problem to some degree and decide to try to solve it, creative strategy spends most of its time and effort on searching for solutions through a what-works scan.

When you run out of time, or when you judge that you have found enough promising precedents, you move to the next phase: creative combination. You select and combine precedents to make a solution. There is no precise formula for creative combination because it matches the flash of insight in a single brain, when precedents come together in your mind. You connect the dots, but not all the dots. You see how one, and another, and yet another together make an innovation that fits your situation and solves your problem.

Last, but not least, the creative combination produces “resolution”: the will to pursue the idea you see. It’s a fact of human nature that people have greatest resolution for their own ideas; that’s why so many consulting reports gather dust on office shelves—the consultants had the idea, not the client. Creative strategy solves this problem by including key leaders at two decisive points: the rapid appraisal and creative combination. That, in brief, is how you can translate the brain’s mechanism for creating new ideas—strategic intuition—into a formal method for innovation: creative strategy.

Excerpted from CREATIVE STRATEGY, by William Duggan. Copyright © 2013 William Duggan. Used by arrangement with Columbia University Press. All rights reserved.

About the Author

William Duggan is senior lecturer in business at Columbia Business School, where he teaches creative strategy in graduate and executive courses. He has given talks and workshops to thousands of executives from companies in countries around the world. His book Strategic Intuition was named Best Strategy Book of 2007 by Strategy+Business.

[/ms-protect-content]