By Lucy McCarthy, Paul McGrath, and Donna Marshall

Our study examined twenty multinational companies and their supply chain disclosure decisions. We found a number of principles that underpin their disclosure strategies: holistic understanding, supportive infrastructure, data requirement knowledge, essential information interpretation, strategic alignment, mitigating the information burden and communicating good news.

Introduction

Recurring corporate scandals from incorrectly labelled horse meat, unsafe toys, illegal dumping, to exploitative work practices continue to keep the issue of supply chain disclosure to the fore as a key strategic concern. Here we take supply chain disclosure to mean the release of accurate, comprehensive and cogent information about the supply chain into the public domain.

While improved supply chain disclosure is generally regarded as a positive development by most stakeholders, it can highlight a range of challenges for managers. As companies grapple with frequently conflicting demands from internal and external stakeholders they are faced with a range of impediments in their attempts to gather ever-greater quantities of high-quality, detailed and reliable data across a multi-tiered, fragmented and geographically-dispersed supply chain.

Our research finds that some companies appear to be managing the process of supply chain disclosure more effectively and strategically than others. Here we summarise our findings in terms of what sets these companies apart.

Principle 1: Holistic Understanding of Current and Future Demand for Supply Chain Information Disclosure

Certain companies tend to have a deep grasp of the demand for improved supply chain information disclosure. They appreciate that prior to developing an appropriate disclosure strategy, the variety of demands for supply chain information need to be fully understood and potentially conflicting tensions managed. One key risk is that a company may disclose too much information exposing core competences and key sources of intellectual property to competitors.

Pressures such as regulation, behaviour of exemplar companies and increasing demands from customers, NGOs, the media and academics need to be identified and managed. Proactive companies can stay ahead of the curve through industry collaborations, such as the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC), which drives disclosure and sustainability best practice in the electronics industry. Other cross-industry collaborations include the Ethical Trade Initiative (ETI), which started in fashion but now encompasses a multitude of other industries.

Principle 2: Supportive and Motivating Infrastructure

To allow for disclosure across functions there must be a supportive culture in place. Proactive companies embed openness and honesty as core values and this culture is reflected across their supply chain. This necessitates top management support and prioritisation and, in many instances, it is strongly driven by the CEO or senior management champion. This facilitates a clear sense of the organisational and societal benefits derived from improved disclosure. An exemplar of this behaviour is the current Unilever CEO, Paul Polman, who was the only business executive invited to help craft the United Nations Sustainability Development Goals.1

Principle 3: Understand Supply Chain Data Requirements

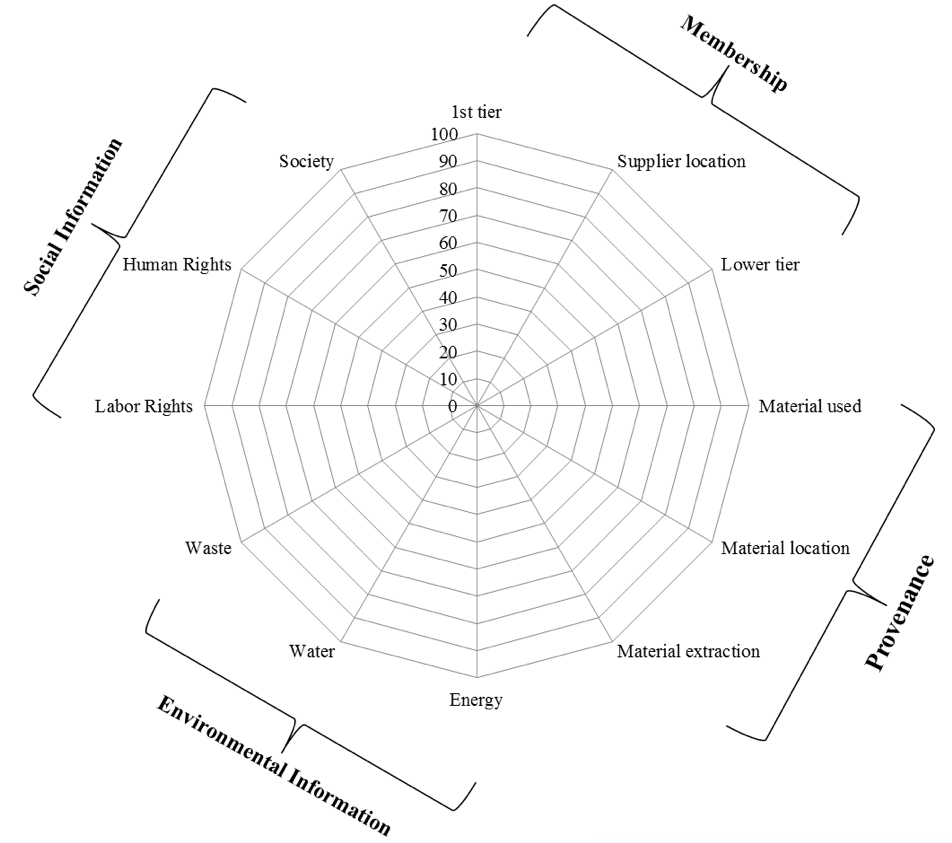

There is substantial variation in the types and levels of supply chain information gathered and released into the public domain. From our analysis, there are four common categories of supply chain information disclosure. We developed the Supply Chain Disclosure Radar2 (see figure below) to aid managers in understanding which data they already have and which they should gather. Managers can use the radar to plot their degree of disclosure on each of the following metrics, membership, provenance, environmental information and social information. Nike, for example, is actively gathering and disclosing information on all four categories.3

Figure 1: Supply Chain Disclosure Radar

Principle 4: Gather and Interpret Essential Information

Many managers have limited knowledge of the supply chain information already available to them. In forward-thinking procurement departments supplier evaluation and selection systems are fairly sophisticated and involve extensive information capture. Companies that already have lean or agile systems in place are likely to have details on multiple-tier supply chain membership as well as provenance information. With the gathering momentum for more sustainability in companies and supply chains, social and environmental criteria are widely used for supplier selection.

For example, Nike gathers sustainability information for their supplier performance scorecards. This means gathering information from different departments and different software systems. However, once identified and collated, templates are easy to update. Using the radar, managers can assess the supply chain information they have access to, the information gaps in the supply chain and be able to resource supply chain information-gathering activities accordingly. Additionally, proactive companies engage in productive dialogue with their suppliers to avoid overburdening them with unnecessary audit requirements.

Principle 5: Strategically Align Information Demand and Disclosure

Once clarity is achieved on supply chain information requirements, there are four main strategies available to managers to guide them on what to do with this information.ii

• Transparent: This means maximum internal and external disclosure of supply chain information. For example, Honest By, the Belgian fashion company, claim to be the world’s first 100% transparent company. They disclose not only membership, provenance, social and environmental supply chain information but also disclose the financial data for their transactions throughout the supply chain.

• Secret: This involves high internal disclosure but little or no public disclosure, due to IP concerns or concern over disclosure of key competences or sources of competitive advantage. Prior to Nike’s decision to disclose their supplier list in 2005, it was common practice to keep supplier lists secret. Since then disclosure is much more common across multiple industries.

• Distracting: This means disclosure of substantial volumes of supply chain information into the public domain but in a manner that is wittingly or unwittingly distracting. Companies engaging in distracting practices, particularly environmental sustainable supply chain practices, have been acknowledged through the Greenpeace Emerald Paintbrush Award for Greenwashing.

• Withheld: Intentional or unintentional failure to collect and disclose supply chain information or deliberately not releasing supply chain malpractice information is regarded as a withheld strategy. Benetton’s initial denial of involvement in sourcing from suppliers located in the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, led to activism and campaigns against the company in 2013 and generated negative publicity for the brand.

While we suggest that there is not an optimal strategy for disclosure, the distracting and withheld strategies have the potential for significant damage to brand reputation. This is particularly the case if there is third party involvement in information gathering, which may lead to unplanned and uncontrolled disclosure. Equally, the effort to prevent disclosure is regarded as deceptive intent and, if revealed, can seriously harm the status of the company.

Principle 6: Manage and Mitigate the Burden of Disclosure

While desirable, effective supply chain information disclosure can come at a high cost, particularly in a geographically-dispersed and multi-tiered supply chain. There is considerable cost in developing information systems to gather, integrate, interrogate and store the supply chain information. Our research indicates an evolutionary change in both the awareness of the burden of supply chain disclosure and the desire to share this burden with suppliers. For example, onerous supplier burden include situations where clothing companies ask for audits or repeated or numerous style changes at short notice. To overcome this, several of the proactive companies in the study provide supports for suppliers such as simplification and streamlining of data, advance communications of impending changes, on-site assistance and training, resource transfer for updating information systems and implementing improvement plans collaboratively with suppliers.

Principle 7: Disclose, Disclose, Disclose

Supply chain information, especially sustainability information, can lead to brand protection and enhancement. Patagonia, Honest By and People Tree, for example, have built their brands on disclosing supply chain sustainability information. Their communication through social media, advertising and their websites highlight supply chain sustainability competence.

However, some companies are still reticent to release supply chain information. Unilever, however, have led the way in demonstrating that even seemingly harmful information disclosure, can actually be beneficial. Unilever, in a long-term collaboration with Oxfam, took the brave step of giving the NGO access to Unilever’s Vietnamese supply chains. Oxfam uncovered multiple worker rights issues during the course of the investigation. However, Unilever, rather than seeing this as detrimental to the company and attempting to withhold this information, accepted it as a useful mechanism to understand issues in their own supply chain. Additionally this may provide impetus for other companies to open their supply chains and allow industry-wide collaboration to improve standards in supply chains. Unilever were praised for their no-holds-barred approach to disclosure in their supply chains and their approach to stimulating action in the industry by Oxfam.

Conclusions

Supply chain information disclosure is an area of growing interest especially for large brands who are now demanding this information and parallel disclosure from their suppliers. For companies who have not disclosed they need to keep in mind seven key principles: have an understanding of the demand for supply chain information, create and maintain a supportive and motivating infrastructure across the supply chain, understand the types of supply chain information they need to gather, effectively gather and interpret essential supply chain information, align this to their corporate and supply chain strategy, manage the burden for their suppliers and, above all, disclose this information to a demanding public.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Authors

Dr. Lucy McCarthy (left) is a lecturer in Queens University Management School. Associate Professor Paul McGrath (centre) and Professor Donna Marshall (right) are faculty members of the University College Dublin (UCD) College of Business and Donna is the Director of the UCD Centre for Business and Society (CeBaS). They are co-authors of the article “What’s Your Strategy for Supply Chain Disclosure?” recently published in Sloan Management Review.

Dr. Lucy McCarthy (left) is a lecturer in Queens University Management School. Associate Professor Paul McGrath (centre) and Professor Donna Marshall (right) are faculty members of the University College Dublin (UCD) College of Business and Donna is the Director of the UCD Centre for Business and Society (CeBaS). They are co-authors of the article “What’s Your Strategy for Supply Chain Disclosure?” recently published in Sloan Management Review.

References

1. An interview with Paul Polman found here: http://fortune.com/2017/02/17/unilever-paul-polman-responsibility-growth/ and a list of the sustainable development goals can be found here: www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

2. Marshall, D., McCarthy, L., McGrath, P. & Harrigan, F. (2016) What’s your strategy for supply chain disclosure? MIT Sloan Management Review, 57(2): 37-45.

3. Nike interactive map: http://manufacturingmap.nikeinc.com/ and sustainable business report: file:///C:/Users/3050225/Downloads/NIKE_FY14-15_Sustainable_Business_Report.pdf