By Fernanda Arreola, Damien Guermonprez, and Renaud Redien-Collot

The skills required to successfully lead one type of enterprise may not fully apply or be relevant to lead a different kind of business, even within the same industry. Adapting one’s approach is often necessary to meet the unique demands of each venture. The following article focuses on the differences between a startup’s business transfer (also known as a takeover) versus an established small or medium-sized enterprise (SME).

The business transfer market is set to grow significantly, with France expecting a 10 per cent increase in 2024 compared to 2023.1 This surge is driven by baby boomers retiring, COVID-19-induced cashflow issues, and managers’ growing interest in partial ownership. France alone has around 80,000 firms for sale, impacting one million employees and leading to 7,000-9,000 takeovers annually.2

New research has attempted to understand how the strategy-building process differs between smaller firms and innovative start-ups. While SMEs are smaller versions of traditional corporations, start-ups are newer entities with innovative technologies or business models. Start-ups’ pace of development is more intense and irregular than that of small businesses.3

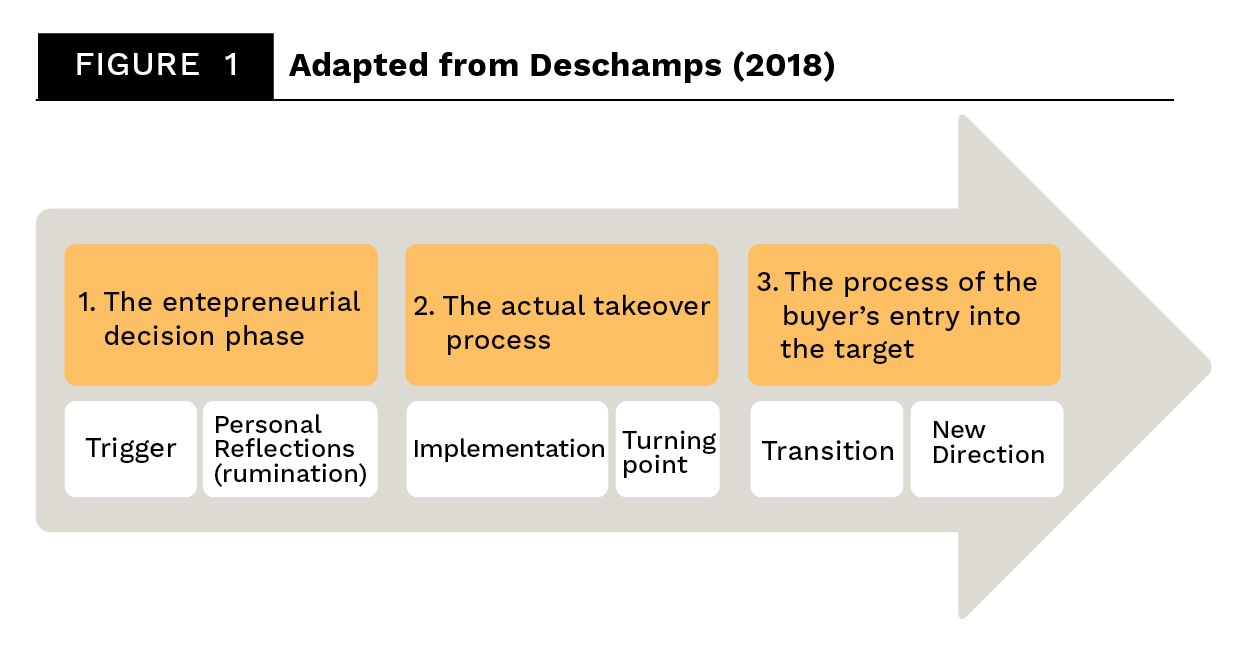

The business transfer process involves three phases and six steps4: the entrepreneurial decision phase (with the trigger to purchase, and the personal reflection), formalization (the implementation, and the turning point), and the buyer’s entry into the target (with the transition and the setting of a new direction). Emotional rebounds during this process can cause ruptures between buyers and sellers. But in the end, if the process is achieved, the acquirers will find themselves with three objectives: creating or defining their job, leveraging the transfer for economic advancement, and setting a strategy.

Building a strategy post-transfer involves identifying new opportunities, creating an entrepreneurial decision-making process, and focusing on performance. Leaders must balance a new strategic vision with their acceptance as legitimate leaders. Historically, one in five external business transfers in France fails after six years due to transparency issues and execution challenges5.

Case Study: Sme VS. Start-Up in the Financial Sector

At 36, Damien Guermonprez had a vision of his future while attending a business meeting in Lisbon. He realized that, like many high-level directors in his organization, he might end up in a non-strategic role before retirement. Determined to avoid this fate, he considered his options. He wanted a career filled with challenges and novelty in a high-paced environment and contemplated owning a firm. A decade later, when he found himself unemployed, he saw this as his opportunity. His main question was: How does a CEO become a small business owner?

Damien’s Origins

Damien was born into a family with a tradition of business ownership. His father was a successful businessman who provided a good standard of living for his seven children. Observing his father, Damien realized that owning and running a business in France could be complex due to bureaucracy and a high tax burden. He also feared the personal and financial consequences of entrepreneurial failure.

After graduating, Damien embarked on a remarkable career in financial services. By 2008, he was the CEO of Oney Bank, the banking division of Groupe Auchan. Under his leadership, the bank’s activities multiplied sixfold, expanded into a dozen countries, and established strategic partnerships with major brands. After nine years at the head of the bank, despite his success, Damien knew he had to evolve and he sought a new challenge.

Damien accepted a proposal to run the French operations of Aon, a global leader in insurance brokerage. However, a year later, a global restructuring ended his mandate, leaving him uncertain about his next career move.

A Unique Opportunity

Damien analyzed his options and decided that acquiring a small firm was the best path forward. He joined Cédants et Repreneurs d’Affaires6, an association for people seeking acquisition targets. Many members were former executives like Damien, lacking entrepreneurial experience. He believed that former CEOs were not always suited to buying small companies, due to their lack of operational management experience and necessary funds.

In 2010, Damien learned that Cetelem Belgium, a subsidiary of BNP Paribas, was for sale. Despite the financial risks, he saw potential due to his experience in consumer credit. He convinced Apax Partners to finance the acquisition, securing a 7 per cent ownership stake and the CEO position. The transaction required an initial investment of 13 million euros.

Transforming Buy Way

Damien rebranded the company as Buy Way, involving employees in the process to build a shared vision.

In September 2010, Damien moved to Brussels to lead Cetelem Belgium. The company had accumulated significant losses, and employees lacked trust in its future. Damien rebranded the company as Buy Way, involving employees in the process to build a shared vision. He implemented a new strategy within 100 days, emphasizing independence from BNP Paribas and collective effort.

Damien’s approach restored employee confidence and encouraged innovation. He introduced training plans, a Buy Way award for innovation, and upgraded IT tools to support e-banking. New partnerships and market entries followed, leading to rapid growth and profitability within a year. Four years later, Buy Way was sold to a London-based investment fund, Damien received his share of the proceeds and reinvested half of them. In 2024, Buy Way bought a Dutch consumer credit company to cover all Benelux markets.

Joining lemonway

In 2015, Damien joined Lemonway, a fintech start-up facing growth challenges. Founded by Sébastien Burlet and Antoine Orsini, Lemonway initially focused on mobile payment solutions. However, competition and financial losses forced a pivot to B2B services, providing payment solutions for platforms. Obtained in 2012, a new Payment Institution license enabled Lemonway to serve marketplaces, which had to delegate their payment operations to trusted third parties for regulatory reasons. The fintech provides them with payment processing, wallet management, and third-party payments within a “know your customer” (KYC)/anti-money-laundering (AML) regulated framework.

As CEO, Damien fostered a dynamic workplace culture and empowered young employees. He secured Series A fundraising and later became Executive Chairman, focusing on relationships with regulators, investors, and the payment industry. Antoine managed day-to-day operations, while Damien drove strategic direction.

Skills and achievements

Damien’s strategic vision and adaptability were crucial in both Buy Way and Lemonway. At Buy Way, he built trust and collaboration, leading to rapid profitability. At Lemonway, he navigated a constantly evolving business model and high employee turnover, maintaining a vibrant and motivating culture.

By 2021, Lemonway had become a leading pan-European payment institution, with significant growth in transaction volumes and revenues. Despite not yet achieving profitability, Damien remained committed to the company’s success. He balanced the customer portfolio and established partnerships with major banks, positioning Lemonway for future growth. Lemonway reached €40m revenues in 2024 and had become highly profitable the year before, certainly doubling its 2021 valuation.

Reflecting on the journey

Damien’s journey from Buy Way to Lemonway highlights the differences in leading an SME versus a start-up. His ability to adapt, build trust, and navigate complex situations was key to his success. He recognized the importance of leveraging existing resources, fostering strong relationships, and maintaining a strategic vision7.

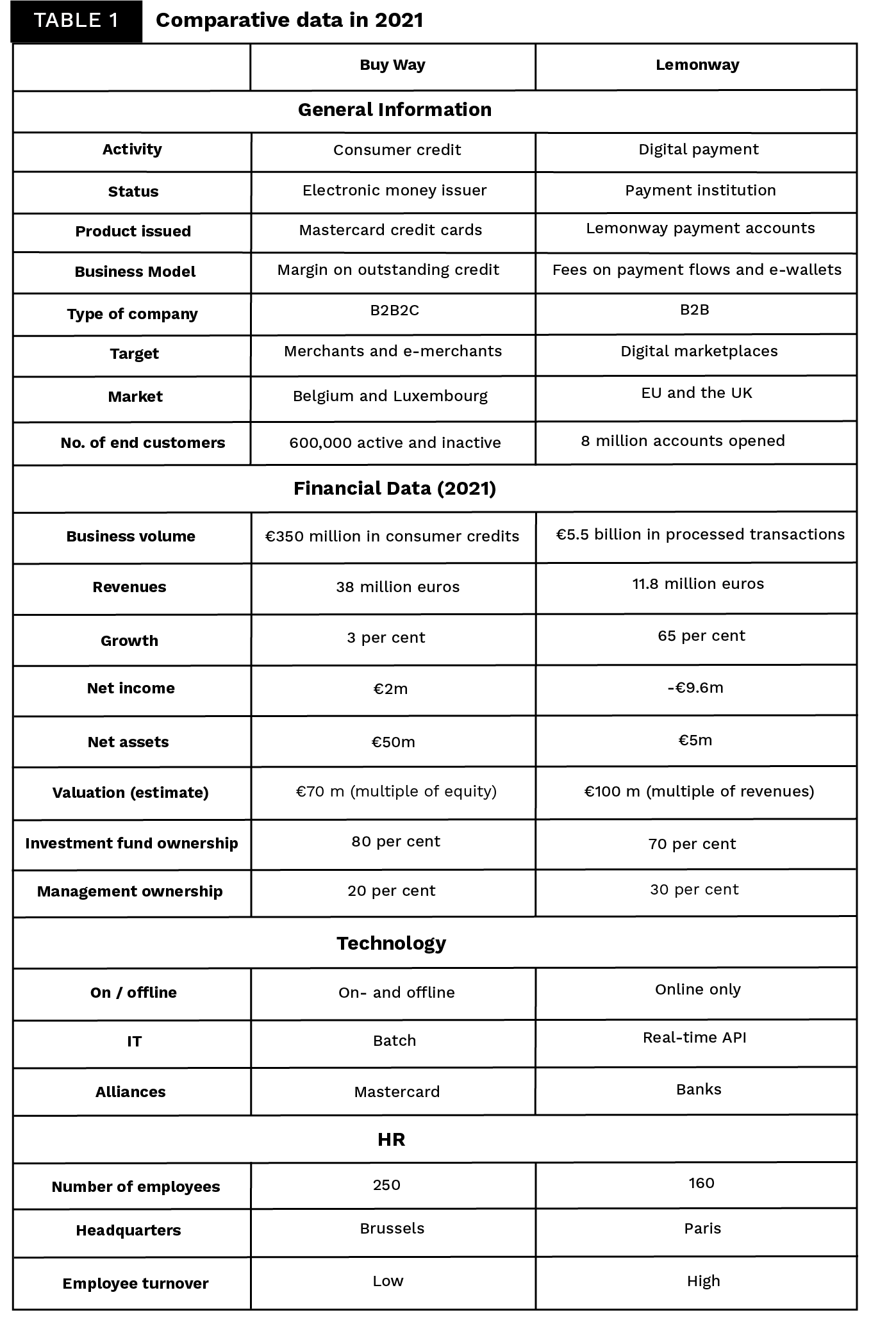

The business transfer processes for Buy Way and Lemonway differed in business model evolution and ownership transfer. Buy Way’s transfer had no impact on its business model, while Lemonway’s new investors influenced key market decisions. Buy Way’s ownership transfer was complete and immediate, whereas Lemonway’s was gradual.

Many differences exist in both companies, starting with the fact that Buy Way continues in its existing market while Lemonway radically pivots. Buy Way’s opportunity is to become autonomous and more agile and to gain market share, whereas Lemonway seeks to exploit a regulatory opportunity. Finally, in the case of Buy Way, Damien is in sole charge of operations. In the case of Lemonway, Damien is associated with Sébastien Burlet, the co-founder, who left in 2018. Damien then forms a dynamic tandem with Antoine Orsini, who takes charge of operations, while Damien adopts a more strategic and political stance, focusing on the company’s external relations (regulators, payments, and crowdfunding associations).

To sum up, Buy Way and Lemonway’s business transfer processes differ in two respects: (1) from the point of view of the evolution of the business model, and (2) from the point of view of the transfer of ownership. Regarding the business model, Buy Way’s business transfer has no impact on its business model. Meanwhile for Lemonway, the arrival of new investors affects many key market decisions, including the consumers, the market where it operates, the size of its clients, and the services proposed. Regarding the transfer of ownership, the ownership of Buy Way is transferred in full and in one go from BNP Paribas to Apax, whereas in the case of Lemonway, the transfer of ownership is gradual. Damien’s approach to legitimacy differed between Buy Way and Lemonway. With Buy Way, Damien was experiencing more direct leadership than he had ever known in his professional career as CEO. At Lemonway, he learned to deploy his leadership skills by participating more directly in the ownership structure.

Business transfers require strategic vision and adaptability, with different approaches needed for SMEs and start-ups.

A final important point is the mobilization of the skills of the new head. Damien’s motivation and self-confidence, bolstered by prior achievements, enabled him to adapt to different leadership roles and create trust. His ability to navigate complex negotiations and pivot strategies was crucial in relaunching Buy Way and Lemonway. Entrepreneurial legitimacy, based on demonstrating and sharing motivation, was key to facilitating change. At Buy Way, he involved staff in organizational changes, while at Lemonway, he built relationships with founders and the core team. High turnover in start-ups made relational legitimacy more challenging than in SMEs.

Meanwhile, not all skills were processed by Damien. During the entry phase of the business transfer, Damien relied on existing teams for information and support, consolidating his legitimacy. Socialization dynamics helped him gain recognition and respect from employees, boosting their motivation.

In summary, Damien’s skills and legitimacy played a critical role in the successful transfers of Buy Way and Lemonway. His ability to adapt, build trust, and navigate complex situations ensured the development and growth of both entities.

Finally, we must point to the fact that the motivation will be stimulated by a sense of self-efficacy. For such a reason the acquirer must have identified one of three possible objectives of the business transfer:

- Using the business transfer to create a job for oneself to no longer be dependent on a sometimes-burdensome hierarchy. This implies that the targeted business is small and is currently capable of providing a salary over the long term.

- Leveraging the business transfer as a vehicle for economic and social advancement. The targeted business therefore has the potential to increase its profitability, resulting in a higher level of income for its manager.

- Leading the business transfer as a personal fulfillment project8. The targeted business has a structure and stable day-to-day operation, providing the acquirers with the possibility to free themselves from repetitive or operational tasks and assume a directive role.

- In summary, business transfers require strategic vision and adaptability, with different approaches needed for SMEs and start-ups. Successful transfers depend on clear strategic action and the ability to navigate complex emotional and operational challenges.

Even if Damien’s case remains unique, we could make the hypothesis that a first experience of taking over an SME can be an excellent test bed for taking over a start-up. Of course, the takeover of start-ups in France and Europe primarily raises the question of the flow of capital that can be mobilized. However, Damien’s leadership with both investors and employees could inspire a new generation of start-up buyers. To improve the management of start-ups in Europe, we may need to encourage more systematic research into serial business transfer, which combines the takeover of SMEs and start-ups.

Fernanda Arreola

Fernanda Arreola Passionate about innovation in financial services,

Passionate about innovation in financial services,  Renaud Redien-Collot

Renaud Redien-Collot