By Terence Tse, Mark Esposito, and Khaled Soufani

A Circular Economy represents not just a paradigm shift that waste is reconstructed to resources through reuse and recreation; it is also about getting more economic boost by resource efficiency and industrial transformation. In this article, Terence Tse, Mark Esposito and Khaled Soufani discuss how a Circular Economy can bring new growth through efficient management of resources.

Circular Economy at a Glance

The world is experiencing mounting resources pressure with a population of nearly 9 billion expected by 2030. The current linear approach of growth is based on the assumption that resources are abundant and cheap to dispose. While there is nothing wrong with it, in principle, the access to the resources, which are finite, has suffered ongoing stress to the pool of available materials and its use and extraction have deteriorated the current situation significantly leading to an alarming sign of massive waste.

The world is experiencing mounting resources pressure with a population of nearly 9 billion expected by 2030. The current linear approach of growth is based on the assumption that resources are abundant and cheap to dispose. While there is nothing wrong with it, in principle, the access to the resources, which are finite, has suffered ongoing stress to the pool of available materials and its use and extraction have deteriorated the current situation significantly leading to an alarming sign of massive waste.

To this extent, in late 2015, the European Commission will present an ambitious circular economy strategy to transform Europe into a more competitive resource-efficient economy. While there is expectation of this new ambitious manoeuvre, a question looms: what is Circular Economy all about?

What Circular Economy is About?

Circular Economy, as it suggests, is a redesign of the future through the restoration and regeneration of new business models and consumption approach of “cradle to cradle”. Through reusing and recycling, “waste” is turned to resource. All resources are handled efficiently as their life cycle. In the broadest sense, Circular Economy can be divided into 3 main areas. First, tremendous waste will be reduced in both production and consumption processes. Second, increasing effectiveness and efficiency of resources by a way called “Servitisation”, which displays a strategy of generating value by adding services on top of products or even replacing just selling products. Lastly, the concept of consumption will be changed from trendy premature update to broadening and lengthening the consumption and use, which leads to longer and wider use of products.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

1. Waste Reduction

Europe is particularly wasteful with the use of resources. The current “take-make-dispose” linear economy approach results in massive waste. Companies exploit materials, use them to make products, sell products to consumers who will abandon them when they do not serve their own original purposes any longer. It is estimated that 90% of the raw materials used in manufacturing becomes waste before the product leaves the factory while 80% of products made get thrown away within the first six months of their life.1 This is way too short compared with the average lifespan of about 9 years for European manufactured goods from furniture to electronic equipment.2

Among all types of waste, Europe creates the highest amount of e-waste in the world on the per capita basis.3 In Germany, almost one-third of the replaced household appliances in 2012 were still functioning, with the increase in the share of replaced appliances after less than 5 years of usage. Take flat screen TVs for instance. Over 60% of the replaced flat screen TVs in 2012 were still functioning, even though the rate of defect has come down. The real reason for replacement is not the failure of performance, but consumers’ desire for TVs with larger screens and better picture quality.4 If e-waste can be explained by a consumer’s mind-set of trying to catch the trend, then food waste is a bit harder to neglect, though it accounts for 30% along the value chain. 46% of fruits and vegetables were lost from the edible mass, mostly thrown away by consumers.5 Since agricultural production uses water and fertilisers, the actual waste of these 30% is more than it appears as it impacts several dimensions at the same time.

Actually, food waste problem has already aroused experts’ attention. Many participants at the Stakeholder Conference on Circular Economy on 25th June 2015 covered this issue and proposed new solutions. One additional example that can be added is the following: 5 to 10% of fruits and vegetables worldwide are cast off due to their unattractive appearance. In France, a campaign called “Inglorious Fruits and Vegetables” took place in 2014 to re-educate consumers’ perspectives on food waste. Instead of wasting the otherwise perfectly edible food, they are sold for 30% cheaper or repackaged and transformed into soups, juices and shakes. 2000+ stores adopted the concept with more than 2,150 tonnes sold in 2014. The initiative was well received and considered a clear success.

Active reduction of waste also involves recycling. However, recycling is only a part of circular economy and has certain loopholes. Recycling can create rebound effects. It has long been said that “recycling is an environmental excuse for instant obsolescence” – it can encourage companies to practise more “planned obsolescence” and consumers to replace goods. Second, there is a difference between closed and open loop recycling. Closed loop is about using waste to make new products without changing the inherent properties of the material being recycled. Open loop recycling, on the other hand, refers to the use of recovered materials to create products that have lower value compared to those produced in closed loop recycling. In other words, not all recycling are equal. Their loss rates are different as well.

2. Servitisation

As the name shows, servitisation originates from the word service. It is a change of concept from selling products to delivering service properties, and is called the “performance model”.

Rolls Royce has played a leading role in servitisation, switching from a solely producer to a combination of an engine producer and a data and maintenance service provider. 80% of Rolls Royce engines are not sold, but rented out on hourly basis of the thrust. After accumulating a treasure of engine operation data through surveillance, Rolls Royce has the capability to offer better maintenance service to airlines, which enables primary revenue stream from payments for performance delivered. Another case is Mudjeans who leases the cotton to its customers, so the company retains the ownership of the material. When the customers no longer want a pair of jeans, they would return them to the company for reuse or turning into vintage.

These two cases proves switching roles to servitisation as instrumental not only to cut down waste but also to experience economic growth in revenue for many of the companies that have ventured this cycle. What’s important is that this is more than a performance model – it is also creating a more effective loop recycling instead of the inferior type of recycling of open loop.

3. Broadening/Lengthening the Consumption

Since we’ve already known that the model of “take-make-dispose” does not lead to anywhere, a new model of “share-reuse-prolong” has been promoted to change the consumption fundamental concept from “consumables” to “durables”. Resources can maximise their life cycle; therefore there is less waste to be dealt with.

Recycling has been talked about for quite some time, and it sounds positive and environmental. However, the problem stays, as only part of the value is recovered. For instance, a reused iPhone retains around 48% of its original value, whereas the value of material that can be recycled and used is just 0.24% of its original value,6 which is stunningly nothing. In short, it makes a lot more sense if the phone can be sold in the second hand market instead of taken apart for reusing components.

Sharing refers to sharing of physical resources, including the shared creation, production, distribution, trade and consumption of goods and services by different people and organisations. The most typical examples are Uber, Airbnb, and Task Rabbit. These companies connect recourses around the world with the owners and consumers, reorganise and optimise the utilisation of cars, apartments and labours, without necessarily owning the assets. Sharing and the Sharing Economy are becoming common uses among the Millennials.

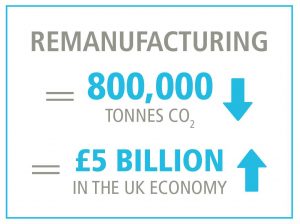

Remanufacturing is the industrial process, which restores worn-out or end-of-life products to like-new condition. In most cases remanufacturing businesses have grown in response to a business opportunity, instead of mission to reduce waste. As a matter of fact, this process saves tens of millions of tonnes of materials worldwide and helps companies make more profit than selling new equipment. Then again it is more affordable to the end user. Remanufacturing is most common where units have very high value or technological content. Compared with recycling, remanufacturing demands a higher skilled workforce; therefore the relative benefit to the UK economy is significantly larger. Currently remanufacturing is estimated to reduce CO2 emission by 800,000 tonnes and contribute £5 billion to the UK economy. The centre for remanufacturing has been established to promote the activity of remanufacturing and other reuse options. Hence, Rolls Royce and Renault have started practising remanufacturing.

Circular Economy and Economic Growth Policy

Circular Economy can bring new growth through efficient management of resources. It’s estimated that disposable income of European households by 2030 could be as much as 11% higher in circular economy relative to the current development path. It is equal to about some 7% more in GDP terms.7 In spite of all benefits presented by Circular Economy, it’s another story how to design certain system to bring out these benefits. There are some key points worth attention.

The pursuit of ever more waste-reduction is important. However, resource productivity could lead to the so-called rebound effect: when the relative prices decrease due to increase of resource productivity, consumers tend to use more, which in turn could negate benefits achieved. Studies in Europe, North America and Japan found that in a long run, a rise of 10% in net income actually increases the demand for vehicles and fuel more than 10% and traffic 5%.8 Therefore, how to limit the rebound effect while maximising waste reduction is worth thorough consideration of policy-makers.

Given the issue that consumers have the tendency to replace products prematurely, which has been greatly promoted by various marketing practice, therefore there is a need to influence businesses to prevent, or at least postpone perceived product obsolescence.9 It is also important to alter consumers’ perceptions of obsolescence, so the average longevity of products can be prolonged.

Circular Economy and Competitiveness

Traditional reliance on technological disruption would only bring limited growth to the economy. More important, it leads to continuous dependence on the resource-based “take-make-dispose” model, which greatly impedes waste-reduction purpose in the long term. On the contrary, Circular Economy represents not just a paradigm shift that waste is reconstructed to resources through reuse and recreation; it is also about getting more economic boost by resource efficiency and industrial transformation. European regional economic competiveness will be greatly strengthened as well.

Traditional reliance on technological disruption would only bring limited growth to the economy. More important, it leads to continuous dependence on the resource-based “take-make-dispose” model, which greatly impedes waste-reduction purpose in the long term. On the contrary, Circular Economy represents not just a paradigm shift that waste is reconstructed to resources through reuse and recreation; it is also about getting more economic boost by resource efficiency and industrial transformation. European regional economic competiveness will be greatly strengthened as well.

The circular economy can be also understood by the following hard facts, that are shaping the landscape for this new paradigm shift, to emerge and integrate the current productive model, with a circular one. More in detail:

Circular economy is expected to achieve overall benefits of €1.8 trillion by 2030, which doubles the benefits seen on the current “linear” development path (€0.9 trillion).

By adopting circular economy principles, Europe can take advantage of the technology revolution including transformation of production and consumption process and increase average disposable income for EU households by €3,000, or 11% higher than the current development path.

This economic uplift would further translate into an 11% GDP increase by 2030 versus today, compared with 4% in the current development path.

Besides financial advantages, the circular model would also benefit households in other ways. One typical example is time cost. Compared with the current development path, the cost of time lost to congestion would decrease by 16% by 2030, and close to 60% by 2050.

From environmental protection point of view, carbon dioxide emissions would halve by 2030, relative to today’s levels (48% reduction of carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 across the three basic needs studied, or 84% by 2050)

Primary material consumption measured by car and construction materials, real estate land, synthetic fertiliser, pesticides, agricultural water use, fuels, and non-renewable electricity could drop 32% by 2030 and 53% by 2050, compared with today.10

Circular Economy and Jobs

While rebooting economic growth on one hand, circular economy has shown strong support in the interaction of natural resource efficiency and employment. Improving resources efficiency significantly ameliorates the labour market. Unlike less labour resulted from traditional industrial developments, circular economy requires more labour, which should be possible with the cut in resources.

While rebooting economic growth on one hand, circular economy has shown strong support in the interaction of natural resource efficiency and employment. Improving resources efficiency significantly ameliorates the labour market. Unlike less labour resulted from traditional industrial developments, circular economy requires more labour, which should be possible with the cut in resources.

A study in Sweden finds that circular economy can increase employment situation by creating an additional 5,000 to 100,000 positions, depending on whether the country could make more use of renewable energy, more efficiency use of energy and better material efficiency (However, it must be noted that it is unclear whether additional jobs would be new ones or replacing existing ones).11 While circular economy extends better result in UK, as a study reveals that adapting a circular economy could be beneficial for job creation. It will bring gross job growth of 30,000 to 500,000, 10,000 to 102,000 net jobs, offsetting 1% to 18% of predicted skill decline in skilled employment over the next decade.12

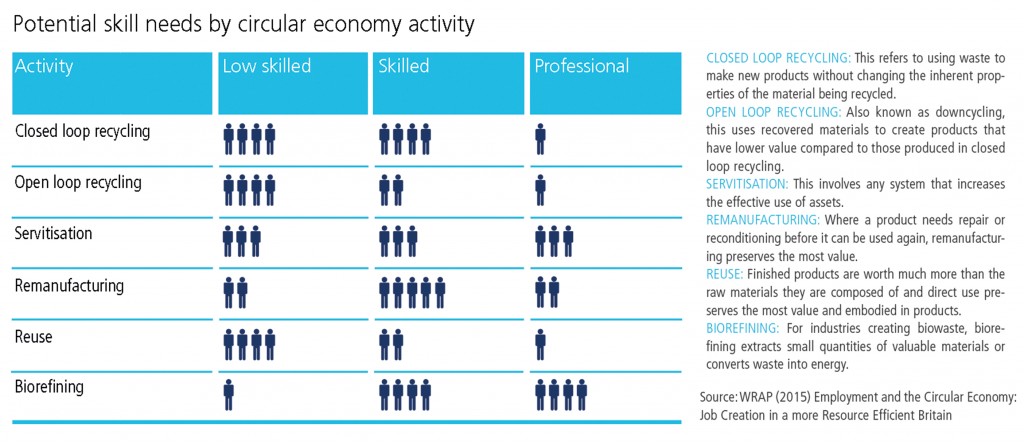

One thing we need to bear in mind is that recycling, as we practise, is only the start of creating the circular economy. As for types of jobs, generally speaking, recycling creates mostly low-skilled jobs. However, as a circular economy requires more sophisticated methods and processes, more high skilled jobs will be generated along the way. Servitisation, Remanufacturing and Bio-refining are the major 3 circular economy activities that would change the structure of the labour market (See Graph). Since currently unemployment happens mostly in the low skilled labour segment, a circular economy can adapt to the current situation, solve contemporary structural mismatch issues and path a great foundation for skilled labourers.

Facing the impending structural change, some companies, sectors and employment segment are likely not to act quickly enough. The result would be a cruelly straight, flat lose-out. Therefore, it’s extremely important to manage the transition, if possible, set up a strategic plan as a top priority for this critical transition and make, of our current decade, the decade of the circular economy.

About the Authors

Dr. Mark Esposito is a Professor of Business and Economics, teaching at Grenoble Ecole de Management, Harvard University Extension and IE Business School. He serves as Institutes Council Co-Leader, at the Microeconomics of Competitiveness program (MOC) at the Institute of Strategy and Competitiveness, at Harvard Business School. Mark consults in the area of corporate sustainability, complexity and competitiveness worldwide, including advising to the United Nations Global Compact, national banks and NATO through various Executive Development Programs. From 2013-14, Mark advised the President of the European Parliament, Martin Schulz, in the analysis of the EU systemic crisis and worked as cross theme contributors for the World Economic Forum reports on Innovation Driven Entrepreneurship. Mark holds a PhD in Business and Economics from the International School of Management, in a joint program with St. John’s University in New York. He tweets as @Exp_Mark

Dr. Mark Esposito is a Professor of Business and Economics, teaching at Grenoble Ecole de Management, Harvard University Extension and IE Business School. He serves as Institutes Council Co-Leader, at the Microeconomics of Competitiveness program (MOC) at the Institute of Strategy and Competitiveness, at Harvard Business School. Mark consults in the area of corporate sustainability, complexity and competitiveness worldwide, including advising to the United Nations Global Compact, national banks and NATO through various Executive Development Programs. From 2013-14, Mark advised the President of the European Parliament, Martin Schulz, in the analysis of the EU systemic crisis and worked as cross theme contributors for the World Economic Forum reports on Innovation Driven Entrepreneurship. Mark holds a PhD in Business and Economics from the International School of Management, in a joint program with St. John’s University in New York. He tweets as @Exp_Mark

Dr. Terence Tse is an Associate Professor of Finance, ESCP Europe Business School & Head of Competitiveness Studies at i7 Institute for Innovation and Competitiveness, an academic think-tank based in Paris and London. In addition to working in governmental advisory capacity, Terence writes extensively and appears on television programmes in China, France, Greece and Japan, discussing the subjects of competitiveness and economic affairs. Before joining academia, he worked in mergers and acquisitions at Schroders, Citibank and Lazard Brothers in Montréal and New York. Terence also worked as a business consultant both independently and at Ernst & Young focusing on UK financial services. He obtained his PhD from Cambridge in Management Studies. He tweets as @Terencecmtse

Dr. Terence Tse is an Associate Professor of Finance, ESCP Europe Business School & Head of Competitiveness Studies at i7 Institute for Innovation and Competitiveness, an academic think-tank based in Paris and London. In addition to working in governmental advisory capacity, Terence writes extensively and appears on television programmes in China, France, Greece and Japan, discussing the subjects of competitiveness and economic affairs. Before joining academia, he worked in mergers and acquisitions at Schroders, Citibank and Lazard Brothers in Montréal and New York. Terence also worked as a business consultant both independently and at Ernst & Young focusing on UK financial services. He obtained his PhD from Cambridge in Management Studies. He tweets as @Terencecmtse

Dr. Khaled Soufani is a Senior Faculty in Management Practice (Finance) at the University of Cambridge Judge Business School. He holds a Masters degree in Applied Economics and a PhD in Financial Economics. He also serves as Director of the Executive MBA and Middle East Research Center.

Dr. Khaled Soufani is a Senior Faculty in Management Practice (Finance) at the University of Cambridge Judge Business School. He holds a Masters degree in Applied Economics and a PhD in Financial Economics. He also serves as Director of the Executive MBA and Middle East Research Center.

Dr. Soufani has published extensively in the area of financial management, corporate restructuring, M&A, private equity, venture capital and family business, and also the financial and economic affairs of small-medium sized enterprises. His work is widely cited and included in policy reports by organisations such as the EU, OECD, and the Institute of Directors and he is on the editorial board of a number of international academic journals. Before joining academia, Dr Soufani worked in investment banking in the area of bond and money market trading.

References

1. Perella, M. (2014) 10 Things You Need to Know About the Circular Economy.

2. Ellen Macarthur Foundation (2015) Growth Within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe.

3. Baldé, C.P., Wang, F., Kuehr, R., Huisman, J. (2015), The global e-waste monitor – 2014, United Nations, University, IAS – SCYCLE, Bonn, Germany.

4. Umweltsamt (2014) Einfluss der Nutzungsdauer von Produkten auf ihre Umweltwirkung: Schaffung einer Informationsgrundlage und Entwicklung von Strategien gegen “Obsoleszenz”.

5. UN FAO (2011) Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention.

6. Benton, D., Hazell, J. and Hill, J. (2013) Resource Resilient UK

7. Ellen Macarthur Foundation (2015) Growth Within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe.

8. Goodwin, P. et al. (2003) Elasticities of Road Traffic and Fuel Consumption with Respect to Price and Income: A Review.

9. Bakker, C. and den Hollander, M. (2015) Six design strategies for longer lasting products in circular economy.

10. Ellen Macarthur Foundation (2015) Growth Within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe.

11. Wijkman, A., Skånberg, K. (2015) The Circular Economy and Benefits for Society Swedish Case StudyShows Jobs and Climate as Clear Winners.

12. WRAP (2015) Employment and the Circular Economy: Job Creation in a more Resource Efficient Britain.

[/ms-protect-content]