By Gilles Paché

Rock tours attract millions of fans each year around the world. But are concertgoers aware of the logistics involved in pulling off impressive concerts? Gilles Paché offers an overview of a fascinating topic that deserves more attention from researchers and practitioners.

While the COVID-19 pandemic put a major halt on rock tours for more than a year, now is the time for legendary bands and singers to return to the stage, after having experimented with virtual concerts on Web 2.0 platforms1 instead of the traditional live gigs. Just like the restoration of a “new normal” in companies, 2023 is a return to the big tours for dozens of artists and bands in the United States2. More broadly, the entertainment industry, including major sporting and cultural events, is experiencing an economic renaissance, as evidenced by the popular success of the 2022 World Cup football tournament in Qatar. If the public is now accustomed to seeing the impressive images of thousands of fans gathered in a stadium for the concert of a famous band, it does not suspect that worldwide tours are the result of the perfect coordination of hundreds of people, a prerequisite for a total ‒ and successful ‒ experience for fans. To illustrate the “logistical overkill” and the stakes involved, one of the best examples is undoubtedly the Rammstein Stadium tour.

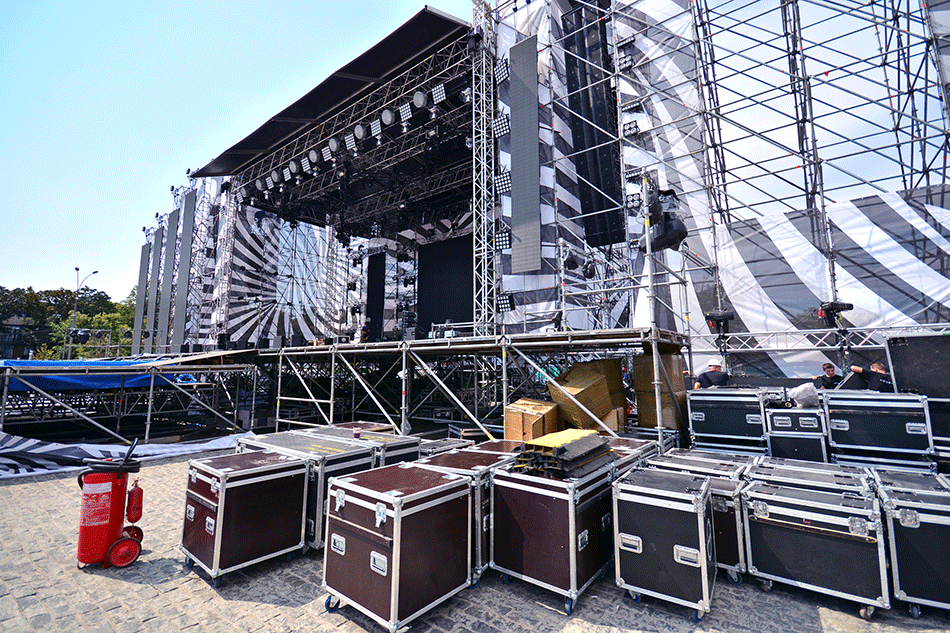

The tour of the German metal band, with its “sulphurous” reputation, uses 180 semi-trailers, more than 1,000 tons of equipment, and two stages 230 feet wide and 130 feet high. It is the biggest rock tour in the world, organised in two sequences, from May to August 2019, then from May 2022 to August 2023, for a total of 104 concerts in Europe and North America with exceptional attendance (including 80,000 people at the Song Festival Grounds in Tallinn, Estonia, on 20 July 2022). Each concert ties up a stadium for 10 consecutive days, while setting up the stage requires seven days of work and the presence of 300 technicians. As for the concert itself, the pyrotechnic effects lead to the burning of 265 gallons of fuel oil per evening, to which must be added the electrical consumption of the 2,000-light shows and 370 music speakers. With the seven Boeing 747 aircraft used to transport all the material, we are very far from the Reise, Reise tour in 2004 and 2005, which had required Rammstein to employ “only” 10 to 13 semi-trailers.

When thousands of fans attend a rock concert, can they imagine the remarkable organisation required for the band or artist to perform? In fact, it is enough to look at the stage, the musicians, or the light shows to realise that first-class event logistics had to be implemented to transport and handle all the equipment. The admiration of the fan who is also an aficionado of logistics will be even stronger when they learn that the band or the artist will reproduce the concert 500 miles away the next day, then 1,000 miles away the day after. In brief, city after city, a rock tour requires strict planning of the moving of goods and people, and the coordination of supply chain operations could be even more complex given that a delay in the delivery of musical instruments or an incident could cancel a concert. In Marseille (south of France), the memory is still vivid of the collapse during its assembly in July 2009 of the roof of the stage planned for a Madonna concert of the Sticky & Sweet tour, causing the death of two technicians and the final cancellation of the concert, as a result of the very tight schedule of the subsequent dates. Behind the human drama, the complexity and fragility of the rock tour supply chains are revealed. But what do they really cover?

When thousands of fans attend a rock concert, can they imagine the remarkable organisation required for the band or artist to perform? In fact, it is enough to look at the stage, the musicians, or the light shows to realise that first-class event logistics had to be implemented to transport and handle all the equipment. The admiration of the fan who is also an aficionado of logistics will be even stronger when they learn that the band or the artist will reproduce the concert 500 miles away the next day, then 1,000 miles away the day after. In brief, city after city, a rock tour requires strict planning of the moving of goods and people, and the coordination of supply chain operations could be even more complex given that a delay in the delivery of musical instruments or an incident could cancel a concert. In Marseille (south of France), the memory is still vivid of the collapse during its assembly in July 2009 of the roof of the stage planned for a Madonna concert of the Sticky & Sweet tour, causing the death of two technicians and the final cancellation of the concert, as a result of the very tight schedule of the subsequent dates. Behind the human drama, the complexity and fragility of the rock tour supply chains are revealed. But what do they really cover?

Moving goods and people

A rock tour is based on a series of concerts performed by an artist or a band in different cities in the same country or in different countries3. Obviously, the volume of a tour varies greatly, and it is not possible to compare a series of a few intimate concerts in halls of 1,000 people with gigantic concerts of a hundred dates in monumental stadiums that can accommodate up to 80,000 people. In the second case, we are dealing with truly multinational events operating on a large scale and managing massive flows whose sequencing of concerts is based on rigorous planning of operations and associated teams. The supply chain associated with the entertainment industry is traditionally subject to specific constraints compared to other, more conventional supply chains, with very little tolerance for delivery delays and scheduling errors. Indeed, each different piece of equipment transported is crucial to the performance of the concert. Thus, it is impossible to imagine that a Rolling Stones or Genesis concert could be held without a set of drums, or that the fans should be asked to come back the next day, when the drums will finally have arrived at their destination, as may happen during occasional stock-outs in a store4.

The transport technologies available at a given moment are at the heart of the management of the operations of a rock tour, and the difficulties are increased when it is necessary to cross borders, with customs clearance phases conducted quickly. The supply chain difficulties linked to transport are the loss of products, their damage, delivery delays, and the lack of security of the flows. To remedy this, the quality of service required by the organisation of a rock tour implies the use of appropriate means of transport. On the ground, special trucks with padded walls and corners are systematically used to protect the (very fragile) equipment. In the air, the use of large Antonov or Boeing 747 aircraft is preferred, but the new generation of aircraft have weight restrictions and smaller doors, which sometimes makes them unsuitable for rock tour supply chain organisation. This reality is not well known by fans, and when aircraft are used, it is more usual to hear about the travels of rock stars, the most famous example being the different aircraft used by the Rolling Stones over the years and decorated with the famous tongue (see illustration 1).

Illustration 1. The public face of transportation:

the example of the Rolling Stones’ aircraft and its famous tongue

When all the equipment arrives at a concert venue, it is unloaded and set up in a predetermined order that never changes: rigging, set, lighting, video system, and audio system. The instruments are the last to be moved onto the stage, and after the concert, everything is repacked in reverse order. But rock tour logistics should not be limited to the management of the physical flow of equipment necessary for the stage performance. One of the particularities of rock tours is that they involve a lot of people whose movements must also be organised from site to site, in reference to a succession of dates chosen according to their economic potential (the number of fans who reside in the trading area, which can be several hundred miles, depending on the country and the fame of the artist or the band). It is not uncommon for rock tours to rely on crews of more than 100 to 150 people, including riggers, carpenters, caterers, security guards, technicians, electricians, and drivers. It is easy to imagine the stakes in terms of accommodation and catering.

Implementation of overcapacity

If the supply chain associated with rock tours emphasises the importance of the volumes to be handled and transported, the major point remains the continuous pressure on the management of the operations. When the price of a ticket is several hundred euros, which does not cool the ardour of the superfans5, it is not possible to cancel the concert because of poorly synchronised supply chain operations that result in a delay in the delivery of one or more essential elements. To cope with such pressure, the solution chosen for the largest tours is the implementation of a systematic overcapacity, otherwise known as “operational slack”. Following Jay Bourgeois III 6:31, it is possible to speak of a “cushion of actual or potential resources which allows an organisation to adapt successfully to internal pressures for adjustment or to external pressures for change in policy, as well as to initiate changes in strategy with respect to the external environment”. In concrete terms, two platforms are used: when one team has finished preparing the concert in city A, a second team starts preparing the next concert in city B.

The case of U2’s 360° tour between June 2009 and July 2011 is impressive because it used three stages for more than two years (the set-up time of each stage was four days), and consequently three supply chain teams: one team working at the concert site; one team dismantling the stage from the previous concert; and one team setting up the stage at the next concert site (see illustration 2). In total, 189 trucks transported the different scenes (390 tons of material), using 380 drivers; 12 buses were also used to manage the 550 people associated with the 360° tour. Even if this rock tour remains an exceptional event, as much in its duration as in its pharaonic dimensions, with a scenic structure resembling a giant spider, it constitutes an emblematic representation of the complexity of the event logistics, which should not weaken in the next years in an experiential stream. Indeed, rock tours must give the fans a unique and memorable experience, with the use of a gigantic stage that has nothing to do with the ultra-minimalist Beatles concerts of the 1960s, with a reduced stage and four musicians playing for only about 30 minutes7.

Illustration 2. A partial view of the U2’s 360° tour logistics

are at the heart of the management of the operations of a rock tour.

The example of the three stages of U2’s 360° tour should not be considered aberrant, as it is in line with the principles of behavioural theory. Overcapacity is the excess of actual or potential resources that help an organisation to overcome internal or external pressures, as indicated by Jay Bourgeois III, facilitating its adaptation when there is a strong time constraint. The presence of a quantity of resources that exceeds the minimum necessary to achieve a given level of production of a service improves reaction capacity and, therefore, customer satisfaction. Harvey Leibenstein explicitly talks about a slack that is essential to the “good life” of an organisation, which he calls “X-efficiency”8. The existence of several stages fits perfectly into this type of analysis, since it reduces the pressure on the teams at the end of a concert to dismantle and transport the equipment to the next city. Without this slack, artists or bands would probably have to reduce the number of dates offered to fans, which would negatively impact their satisfaction, especially with a significant increase in the distance to travel to participate in the unique and memorable experience that is the concert.

Importance of planning

However, it would be wrong to think that the implementation of logistics overcapacities makes operations planning unnecessary. The logistics of rock tours require an upstream definition of all supply activities, with the identification of the various critical tasks whose non-performance ‒ or delayed performance ‒ could block the supply chain, and consequently the execution of the concert in the various locations that have been selected. The organisation of a tour is therefore based on a negotiation process linked to the acquisition of logistical resources from specialised partners, which is comparable to the situation of commercial supply chains. For example, the Averitt company offers customised supply chain solutions based on 100 drivers for OTL 53-feet trailers specially equipped for the entertainment industry (for example, see the description of Drake’s Summer Sixteen tour by Mark Solomon9). This negotiation to obtain logistical resources essential to the development of the succession of concerts is a key element to create the conditions for totally successful control in the sequencing of supply chain operations.

It should not be forgotten that one of the major problems of rock tours is linked to the equipment that must be handled and transported over long distances, under special safety and protection conditions. Accordingly, rock tours, especially when they take place on several continents, rely on excellent project management, which consists of designing and executing a set of operations to obtain a specific result. All project management is subject to the following three constraints: the technical specifications of the project; the material and immaterial resources required to carry it out; and the imperative respect of the deadlines for delivery. This is the case for rock tours, which rely on a set of processes throughout the life cycle, from the launch phase (beginning of the tour) to the closing phase (end of the tour). For rock tours, there is also the consistency of the quality of the infrastructure used. With increasingly elaborate tour productions and strictly timed concerts, the infrastructure is a decisive factor for the fastest-possible assembly and disassembly of the scenic structure.

While logistical planning is essential to avoid last-minute “bricolage”, in other words making do with the means at hand in an emergency, it does not prevent unexpected difficulties due to an unfavourable environment. This was the case for Coldplay’s Music of the Spheres tour in 2022. Faced with the climate challenge, to which its young fans are very sensitive, the band organised sophisticated logistics to offer an “eco-responsible” tour, with the use of solar panels, a portable battery, and a kinetic floor. In addition, as well as the biodegradable confetti and eco-cups used during the concerts, the audience was invited to pedal to generate green energy and allow the concert to continue. However, Coldplay acknowledged huge supply chain problems as, in trying to make their tour green, the band quickly ran into difficulties transporting equipment at an acceptable cost. An interruption of the Music of the Spheres tour was considered, before unexpected sponsors prevented a financial crisis and allowed the tour to continue. This example is interesting because it highlights the fact that the issue of implementing sustainable supply chains affects the entertainment industry as much as the retailing and manufacturing industries and, for that reason, knowledge transfers are of obvious interest.

A key topic to be explored

Rock tours attract millions of fans each year around the world. But are they aware of the logistics involved in pulling off impressive concerts? Indeed, for a rock tour to succeed, it requires the transport of a lot of goods, with the teams in charge of handling them, but also of assembling and disassembling the different elements of the stage structure every day. These teams must be fed and housed city after city, requiring efficient hospitality management. In comparison, transporting 25 tons of fruit and vegetables from Spain to Norway or importing 40 containers of toys from China is “a piece of cake”. A rock tour lasting several months or even years requires moving huge scenic structure, fragile musical instruments, hundreds of costumes, and giant video screens. Of course, when a rock tour is launched, there is no room for delays, damage, or scheduling errors. Each leg of the tour must be tailored to the specific laws and customs regulations of each country, which can be very demanding.

Paradoxically, the rock tour supply chain has not been tackled head-on by management research, which leaves the field open to carry out work in cultural economics, sociology, musicology, or ethnology, as if the management of rock tour flows over several hundred thousand miles did not raise any specific issues. It is surprising when we learn that, in the late 2010s, the various tours of the Rolling Stones since 1962 had led the band to travel more than a million miles, or 43 times around the Earth! However, the specific constraints associated with tours are undeniable, and they deserve special attention. It is enough to consult Google Scholar to see the very low number of works dedicated to the rock tour supply chain stakes; an example is the recent doctoral dissertation of Gabrielle Kielich in communication studies10, and the almost total absence of academic articles published in the best world journals in logistics and SCM. This lack of interest is regrettable and is undoubtedly rooted in a purely “artistic” vision of rock tours, for which “the stewardship will follow” (“l’intendance suivra”), to quote General de Gaulle’s famous sentence. At best, some observers think vaguely that the logistics can be outsourced in total confidence to specialised competent logistical partners like Averitt.

This approach cannot be satisfactory when we consider the economic benefits of rock tours, especially for the cities hosting the concerts (even if it remains difficult to quantify these benefits precisely; for example, the fans’ spending on food products and accommodation at the concert venue). Even more importantly, significant business opportunities exist, especially for graduate students who have chosen to specialise in supply chain management. This field of event logistics can attract talent, because it offers a stimulating environment that would, for example, allow bright students to link their passion for music with their job, because finally, as the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel11:22 wrote, “Without passion nothing great in the world has been accomplished.” By way of comparison, for many years, MBA programmes in sports management have been developed in Europe to feed the professional sports sector, especially football. Tens of thousands of students passionate about sports are trained in marketing, finance, HRM, or management control to improve the governance of well-known clubs. This is not yet the case for the logistics management of rock tours. A word to the wise!

About the Author

Gilles Paché is Professor of Marketing and Supply Chain Management at Aix-Marseille University, and Director of Research at the CERGAM Lab in Aix-en-Provence, France. He has more than 600 publications in the forms of journal papers, books, edited books, edited proceedings, edited special issues, book chapters, conference papers and reports, including the recent two books La société malade de la Covid-19: regards logistiques croisés (2021), and Variations sur la consommation et la distribution: individus, expériences, systèmes (2022).

Gilles Paché is Professor of Marketing and Supply Chain Management at Aix-Marseille University, and Director of Research at the CERGAM Lab in Aix-en-Provence, France. He has more than 600 publications in the forms of journal papers, books, edited books, edited proceedings, edited special issues, book chapters, conference papers and reports, including the recent two books La société malade de la Covid-19: regards logistiques croisés (2021), and Variations sur la consommation et la distribution: individus, expériences, systèmes (2022).

References

- Rendell, J. (2021). “Staying in, rocking out: online live music portal shows during the coronavirus pandemic”. Convergence, Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 1092-111.

- Anonymous (2023). “Concert season is here: upcoming music tours in the USA”. The European Business Review, 10 February. https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/concert-season-is-here-upcoming-music-tours-in-the-usa/

- Reynolds, A. (2022). The live music business: management and production of concerts and festivals. Routledge, New York, 3rd ed.

- Chishty, M.-A., Loya, S., Ismail, S., and Zaidi, H. (2015). “Consumer response in out-of-stock situation at a retail store”. International Journal of Humanities & Social Science, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 180-8.

- Anonymous (2022). “How much money does it take to be a music superfan in the UK?”. The European Business Review, 19 September. https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/how-much-money-does-it-take-to-be-a-music-superfan-in-the-uk/

- Bourgeois III, J. (1981). “On the measurement of organisational slack”. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 29-39.

- Cottet, P., and Paché, G. (2022). “Living a memorable consumer experience: the epic of the Beatles concerts (1963-1966)”. Journal of Marketing Development & Competitiveness, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 33-47.

- Leibenstein, H. (1978). General X-efficiency theory and economic development. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Solomon, M. (2019). “Rock, roll and the road: how trucker guys and gals bring the music”. Freight Waves, 16 July. https://www.freightwaves.com/news/rock-roll-and-the-road-how-trucker-guys-and-gals-bring-the-music

- Kielich, G. (2021). Road crews and the everyday life of live music. Unpublished doctoral dissertation in Communication Studies, McGill University, Montreal.

- Hegel, G.-W.-F. (1857/2011). Lectures on the philosophy of history. WordBridge Publishing, Aalten.