By Adam Bock and Gerard George

The combination of globalisation, Moore’s law and ubiquitous information have transformed industries into fluid, rapidly-changing landscapes. Today’s competitor is tomorrow’s partner and next year’s customer. In this article, the authors elaborate on the four stages of Business Model Cycle which managers, especially at new and growing ventures, can reflect on as they aim to build and evolve organisations to explore shifting seas and exploit opportunities.

“It’s the business model, stupid!” – Esther Dyson

The pace of business innovation and change is accelerating. To adapt, entrepreneurs and executives have adopted (and exhausted) a variety of management tools: blue ocean strategy, business re-engineering, organisational learning, TQM and disruptive innovation, just to name a few. But the combination of globalisation, Moore’s law and ubiquitous information have transformed industries into fluid, rapidly-changing landscapes. Today’s competitor is tomorrow’s partner and next year’s customer. How can managers, especially at new and growing ventures, build and evolve organisations to explore these shifting seas and exploit opportunities?

It’s all about the business model.

For more than a decade, we have been studying business models at small and large firms. We interviewed hundreds of entrepreneurs and managers. We analysed IBM’s Global CEO survey data covering 750 CEOs of large and tech-savvy firms. The business model has emerged from an ignominious birth in the dot-com era to become the dominant tool for exploring and exploiting opportunities. As the world of business accelerates, your firm’s business model will only become more critical.

There is only one problem. The hard truth is that no one really knows why some business models work and others fail. That is precisely why you need to diagnose and test your business model before you implement it. Equally important, you need to know when your business model must be updated and evolved.

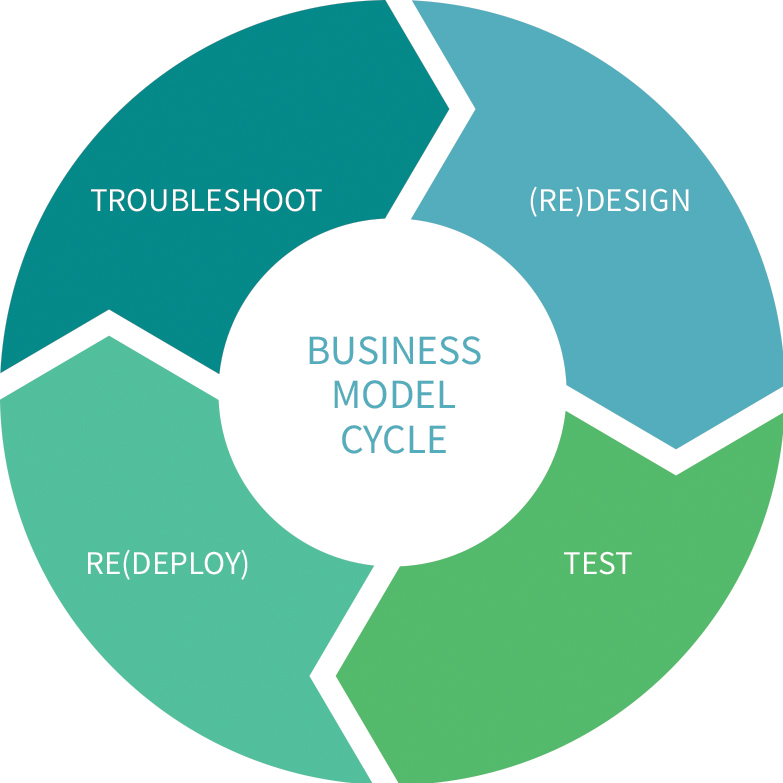

In The Business Model Book, we demonstrate the general process for designing, evaluating, testing, and adapting business models. The business model cycle (Figure 1) can be used at every organisational stage: from pre-launch ideation to rejuvenating a multinational. You probably have most of the tools and capabilities ready to hand; you just need to use them effectively to build the right business model at the right time.

Figure 1: The Business Model Cycle

(from The Business Model Book, Pearson 2018)

The four stages of the Business Model Cycle are troubleshoot, re(design), test, and re(deploy).

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

Troubleshoot

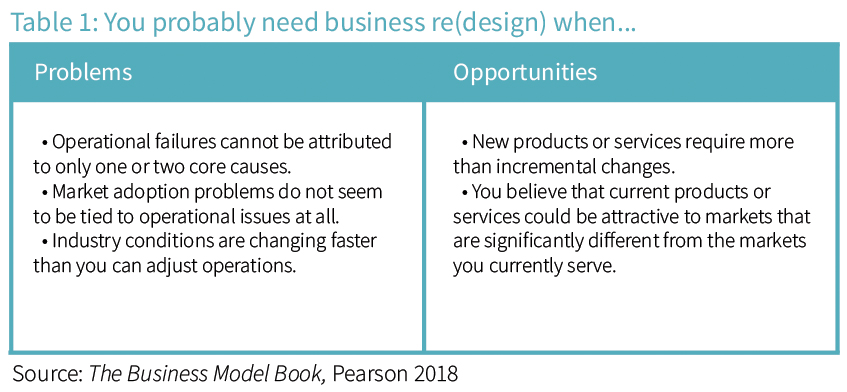

The first step is arguably the simplest. Do you need to (re)design your business model? If your business is struggling with only one or two specific challenges, such as operational inefficiency or brand erosion, then business model (re)design is overkill. Changing your business model carries significant risks. If you are pre-venture, then by definition you are at re(design). Similarly, if your organisation is facing multiple failure modes, then business model (re)design may be your best option. Business model re(design) starts with either problems or opportunities. Table 1 shows the symptoms that point towards business model re(design). In The Business Model Book we also discuss the symptoms commonly mistaken for business model failure.

Cellular Dynamics needed business model re(design). Despite being the world leader in stem cell technology the company was having trouble raising the venture capital it needed. It was also struggling to prioritise across tools and therapeutics opportunities, which had significantly different risk-reward profiles. The executive team implemented a platform-based business model based on induced pluripotent stem cell technology. They simplified the organisational structure and prioritised manufacturing capabilities over therapeutics development. The business model re(design) led directly to $30 million in new venture capital and being recognised by the Wall Street Journal as the most innovative company in the world. Less than five years later, Cellular Dynamics was bought by Fuji for $307 million.

(re)Design

Designing a great business model is not rocket science. Using the right tool at the right time, however can dramatically speed up the process and facilitate iterative testing. Creative spark and experience-based intuition will serve you well, but the right tool will convert all that cleverness into something that can be tested and implemented.

Maurya’s “Lean Canvas” and Osterwalders “Business Model Canvas” are powerful, effective maps for building business models. But they are best used for early stage and growth ventures, respectively. What if you are still exploring opportunities in the ideation stage, whether as a new venture or existing business seeking rejuvination?

The RTV-N model, which emerged from our interviews with entrepreneurs, is a great starting point for any business model analysis. And, when complete, it can easily feed into either the Lean or Business Model Canvas as you explore the opportunity in more depth.

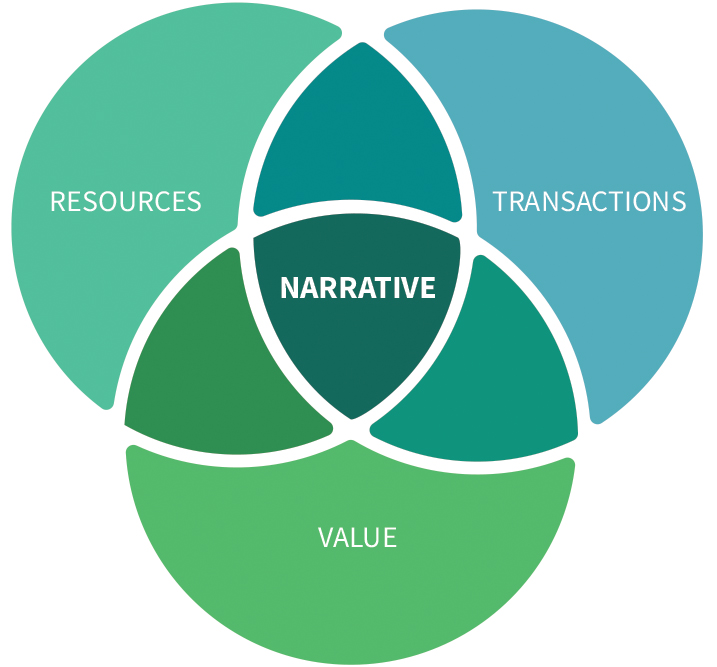

RTV-N stands for Resources, Transactions, Value, and Narrative, as shown in Figure 2. You can download a worksheet template for this model at www.bizmodelbook.com.

Figure 2: The RTV-N business model framework

RTV-N is powerful because it focuses directly on the key business model components. What specialised and hard to copy resources separate your venture from competitors? What are the transactions that link your venture to partners, customers and ecosystem participants? How is value created by resources and captured by transactions? At the heart of the business model, the narrative links all the elements together into a coherent story that resonates with stakeholders. In The Business Model Book, we provide step-by-step guidance to use this model, as well as the other canvases. The trick is to know which one will serve you best, based on your organisational stage and business model needs.

Professor Shane Farritor at The University of Nebraska developed MRail, a novel laser-based system to test rail deflection in real time to identify sections of railroad track that might fail and cause an expensive derailment. The RTV-N framework reveals that the value in the business model is not the equipment that does the measuring but the cumulative longitudinal data that tells the rail company where, across thousands of miles of track, to send inspection crews. The coherent narrative describes a service, not a product at all! As the business model evolved, it also revealed that the right service provider would need to be an industry participant to facilitate the system’s use on existing equipment. After combining good business model design with further advances in the product design, Farritor sold the technology to Harsco Rail. MRail remains the only vertical track deflection solution on the market.

Test

If RTV-N shows that your business model is coherent, then it may be viable. But there is only one way to be sure. Test it.

Testing a business model is like prototyping. You need to put the logic behind your business model in front of stakeholders who can provide real-world feedback. The key is not whether your business model creates value in general, but whether the configuration of resources and transactions creates value for those stakeholders. That can include customers, supply chain partners, investors and customers. A sustainable business model does not only extract value from other industry participants; it generates entirely new value. Great business models make the pie bigger for all the stakeholders connected to it.

Depending on your resources and stage of development, you can conduct thought experiments, information tests and pilot tests. Using the RTV-N framework, a thought experiment can explore alternative resources, transactions and value creation mechanisms. Information tests seek to confirm key assumptions about the business model, such as whether key customer segments will adopt new technologies or products. Information tests are effective when the hypotheses can be addressed quickly with limited resources and the results will be meaningful to either (re)design or (re)deploy the business model. Pilot testing, the most powerful option, requires simulating organisational interactions with stakeholders and partners. Just putting the product in front of customers is not enough!

For example, Adam Sutcliffe’s Orbel hand sanitiser was a significant innovation compared to wall-mounted or table-top dispensers. The patented design used rollerballs to dispense the gel sanitiser; health care workers could clip the Orbel to a pocket and then run one hand over the rollerball pad. The motion is the same that we use to wipe off our hands – the Orbel transforms a germ-transferring habit into a sanitising habit! When Sutcliffe tested product prototypes in a hospital, the nurses loved it so much they did not want to give the prototypes back. But Sutcliffe and the team he hired were less successful testing the business model. They tried to work through third-party distributors without clearly establishing whether the target segment was health care practitioners, health care facilities or consumers. Without business model testing, they were unable to generate a clear revenue model that accounted for distribution and sales processes. Although the Orbel invention won numerous awards and accolades for its potential to address serious health care challenges such as MRSA, the Orbel business model has not yet achieved its potential growth and success.

By contrast, FanDuel effectively pilot tested its business model into existence. After a failed social network venture, the team and its investors identified online fantasy sports as a high-potential opportunity. One of the founders, Tom Griffiths, described their early commercialisation efforts as an effort to put every possible kind of fantasy sports game on their site to see what users would actually join. FanDuel was simultaneously testing products and the business model by tracking data on customer choices and payments. The team generated dozens, hundreds of hypotheses about sports fan behaviour. For example, how much did team loyalty matter when fans built fantasy teams? Did they specifically want to bet against fans of rival teams? Which team and player statistics capture fan interest? FanDuel had the right team and timing, but it was business model testing that drove FanDuel revenues from less than $5 million in 2012 to more than $150 million in 2016.

(re)Deploy

When your (new) business model is ready to go, all you can do is take the leap.

Business model innovation is emerging as the ultimate tool for disrupting industries and creating quantum leaps in value creation. Business model innovation can be incredibly rewarding. For example, Apple has captured roughly 25 percent market share of music industry revenues, despite being, for all intents and purposes, purely an intermediary. As we’ve reported previously in this journal, the IBM Global CEO survey showed that outperforming firms were disproportionately business model innovators, rather than product or process innovators.

But business model change and innovation can be extremely risky. We have documented extensive cases of high performance firms with great teams who discovered that business model innovation simply does not always work.

Launching a business model requires investment and effort; but you are not committing to that business model forever. You cannot predict everything; your best bet is agility. To stay agile when you (re)deploy your business model, remember the wisdom of Henry David Thoreau: “Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity!”

Ensure that the effort is led by one key leader. Keep organisational structures clear and simple. Find ways to offload non-critical functions to other people and organisations. It is difficult enough to (re)Deploy the core business model; your managers and teams should not have their attention taken up with non-essential activities and issues.

Perhaps the greatest challenge when (re)deploying a business model is maintaining or adjusting culture to suit. Maintaining a creative culture, more than any other factor, will determine whether your business model innovation process can adapt to change.

The Development Bank of Singapore (DBS) discovered this early on when it made the decision to transform itself the world’s best digital bank. It was not enough to get immersed in cloud computing, fintech startups, or even understanding the emerging customer needs of fully digital consumers and businesses. DBS recognised that everything it did would have to revolve around innovation, team-based process and constant learning. The new business model was predicated on the belief that all banking would need to be re-centred around mobile utilisation, not just a few apps on top of the legacy infrastructure. CEO Sebastian Paredes described this as becoming a 20,000-person start-up. The company added “running an experiment” to every employee’s key performance indicator requirement. The company ran more than 1000 experiments around new products and customer experience in 2015. DBS proves that you do not have to be a startup to act like a startup; when you (re)deploy your business model, it is exactly what you want to do.

Back to the Business Model Cycle

The most challenging lesson about business model change and innovation, however, is that you never reach the end. The business model cycle, once completed, simply brings you right back to your starting point. No business model works forever.

The bad news: our research showed that prior success with change was not correlated with successful business model innovation. In other words, business model innovation may not improve with practice! We suspect that this is because executives have not found a way to codify and manage the non-intuitive leaps required for business model innovation.

Yet some firms have found a way: Apple disrupted both the music industry and the mobile phone industry in the space of five years. Return Path turned email marketing upside down with a sender whitelist and decertification of third-party content. Khan Academy pioneered free online mathematics lessons and now seeks to make any educational topic available to anyone in the world. In other words, the capabilities for continuous business model innovation are out there, embedded in firms that embraced innovation, creative culture, and an entrepreneurial approach to business models.

Industries will become globalised and competitive. The pace of technology-driven change will increase. Information and communication systems will become both more ubiquitous and more valuable. Opportunities will be identified sooner and exploited more quickly. The ventures that survive and thrive will the ones that implement the right business model at the right time.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Authors

Adam J. Bock is currently a Lecturer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is also a serial entrepreneur, financier and venture consultant. He co-founded four life science companies including Nerites Corporation and Stratatech and managed multiple angel investing networks, facilitating $10 million of early stage investments. He is the co-author, with Gerry George, of The Business Model Book (2018), Models of Opportunity (2012), and Inventing Entrepreneurs (2009).

Adam J. Bock is currently a Lecturer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is also a serial entrepreneur, financier and venture consultant. He co-founded four life science companies including Nerites Corporation and Stratatech and managed multiple angel investing networks, facilitating $10 million of early stage investments. He is the co-author, with Gerry George, of The Business Model Book (2018), Models of Opportunity (2012), and Inventing Entrepreneurs (2009).

Gerard George is Dean and Lee Kong Chian Chair Professor of Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Lee Kong Chian School of Business at Singapore Management University. He joined SMU from Imperial College London where he was Deputy Dean of the Business School. He also held tenured positions at the London Business School and at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He was awarded Fellowship of the City & Guilds of London Institute for his contribution to further education and research.

Gerard George is Dean and Lee Kong Chian Chair Professor of Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Lee Kong Chian School of Business at Singapore Management University. He joined SMU from Imperial College London where he was Deputy Dean of the Business School. He also held tenured positions at the London Business School and at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He was awarded Fellowship of the City & Guilds of London Institute for his contribution to further education and research.