By Kristine Marin Kawamura and Simon L. Dolan

Innovation has been consistently found to be the most important characteristic associated with organisational and market success. Some companies are brilliant at innovation while others, for all their efforts, cannot sustainably deliver successful innovations. Why do some firms succeed while others fail? This paper proposes that sustainable innovation occurs when leaders and managers are able to break open their innovation search space by emphasising need pull innovations and harnessing the innovation energy of user- and customer-innovators; develop the strategic dynamic capabilities of values-based innovation culture and management system; and transition their management systems to “Managing by Sustainable Innovation Values” culture (MBSIV). With its three essential axes (economic-pragmatic, ethical-social, and emotional-developmental), MBSIV allows management to develop a values-based, high-involvement, performance-oriented innovation culture, which becomes a distinctive competency for the firm for delivering innovatory and competitive advantage.

As the Greek philosopher Heraclitus once said, “The only thing constant is change.” Not only is change central to the universe, it is a central component in all human, organisational, and societal development: the child grows into the adult; the organisation strategically adapts in response to the influence of environmental forces; or, as a society shifts from a nomadic band of primitive hunter-gatherers to an egalitarian society, it becomes more complex and centralised, demanding more technology, innovation, governmental regulation, and leadership1. Change, too, is a vital aspect of science, which further associates the notion of change with energy. According to physics, energy is a property of all objects and is transferable among them via fundamental interactions. Energy can be converted, changed, into different forms, but it cannot be created or destroyed. Energy, too, may be lost, unavailable for work, which in turn is measured by entropy – normally viewed as a measure of the system’s disorder.i

Organisations, too, can be associated with notions of change and energy. Change serves as a catalyst for the successes and failures of 21st century organisations and societies that must withstand and even flourish in the midst of the risks associated with numerous economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal, political, and technological transformations: un- and underemployment; the flair up of interstate conflicts; terrorism; the energy, fiscal, and water crises; profound social instability; large-scale voluntary migration; and critical information infrastructure breakdown2. Furthermore, the energy and vitality of individuals and organisations have been found to depend on the quality of the connections among people in the organisation and between organisational members and people outside the firm with whom they do business3. Research shows that organisational leaders can “spark” a unifying vitality and commitment among employees and unleash their firms’ potential for creativity, initiative, and innovation by developing, or uncovering, an organisation’s unique purpose4. Purpose is intimately connected to the values of both the organisations and its leaders and may be engendered by the use of values-driven leadership and management systems5. Entropy, too, may occur in organisations when self-organising living systems are ignored or when their strategies and cultures are not based on wholeness, interdependent relationships, open communication, shared information, shared values, and trust6.

Innovation, consistently found to be the most important characteristic associated with organisational and market success7, is also deeply rooted in the notions of change and energy. Innovators seek to change the status quo, exploring how to do something different or do something better, how to turn opportunity into new ideas and putting them into widely used practice8. They look for ideas from multitudes of sources that trigger the process of taking an idea forward, revising it, weaving its’ different strands of “knowledge spaghetti” and relational connections together towards a useful product, process, or service8.

Innovation is rooted in its own source of energy: innovation energy has been described as the ‘pattern’ behind successful innovation, which is the confluence of three forces: an individual’s attitude; a group’s behavioural dynamic; and the support an organisation provides for enabling innovation8(p.141). At the heart of innovation is the ability of leaders and managers to energise and engage the people of the firm –to get them fired up about the firm’s bold vision (right attitude), breaking established behaviour patterns so that people employ “right” innovation behaviours and create the “right” organisational support, environment, and leaders to powerfully fuel innovation energy8. Leaders generate, harness, and manage innovation through developing a values-based, high-involvement innovation environment, culture, and climate. They create a high-involvement innovation environment – a condition where everyone is fully involved in experimenting and improving things, in sharing knowledge, and in creating an active learning organisation – by building a shared set of sustainable innovation values that bind people together in the organisation and enable them to participate in its development, driving both incremental and radical innovations and maximising organisational performance8,9,10,11. A high-involvement innovation climate is characterised by emotional safety, respect, and joy derived through emotional support and shared decision-making, creative self-efficacy, reflection, open communication, and divergent thinking12.

This paper proposes three interrelated strategies for creating a high-involvement innovation environment, culture, and climate:

1.Break open the innovation search space by emphasising need pull innovations, harnessing and leveraging the innovation energy of user- and customer-innovators;

2. Recognise that developing a values-based innovation culture served by a values-based management system serves as a strategic dynamic capability for the firm that enables it to capitalise on its strategic human and innovation resources; and

3. Transition its management system to Managing by Sustainable Innovation Values (MBSIV) – a values- and innovation-based leadership tool that motivates innovation energy, enhances user- and customer-innovation, and address the many management challenges of the 21st century.

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

The Evolution of the Innovation Space

Innovation occurs within an innovation space (defined by paradigm, product, position, and processes) within which an organisation can operate and innovate13. Traditionally, the boundaries of the innovation space were based upon the firm’s internally-based resource capabilities along with those developed through strategically-developed partnerships along its value chain. Today’s best innovators are breaking open the boundaries of the innovation search space. Several strategies have emerged: breaking industry compromises to release enormous sources of stored value and achieve breakaway growth14; creating “blue oceans,” untapped market spaces that are ripe for growth15; and disrupting the industry’s cost structure by working at the fringes of a mainstream market, addressing unmet user needs16.

Expansion of Need Pull Innovation

This paper proposes that the firm’s innovation search space and landscape will also be further expanded and redefined through the growth of need pull innovation, which is correlated with the emergence of user- and customer-based innovation. As opposed to knowledge push innovation that underlies large organisational R&D departments, need pull innovation is developed in response to real or perceived needs for change from the buyers, adopters, clients, and/or users of products and services8.

Need pull innovation arises from the evolutionary and transformative forces of globalisation, digitalisation, and virtualisation17, which have fueled the innovatory forces of democratisation, open and networked innovation, and personalisation, and mass customisation/consumerisation (i.e. a market size of 1). Democratisation affects firm capabilities, as computer hardware and software democratise access to tools that were only possible in a firm environment before. This makes citizens more capable of engaging in their own solutions (innovations) for their problems. Open and networked innovation affects firm coordination, as the Internet has greatly improved the ability of users to coordinate their efforts, so that more complex endeavours can now be produced as a result of coordinated individuals18. The move to personalise firm capabilities to “market sizes of 1” allows firms to meet individual user’s needs with unique, inimitable solutions19.

User- and customer-centred innovation strategies and practices, in turn, are also emerging, offering advantages over firm-centric innovation development systems: the individual is no longer simply regarded as a buyer with needs for manufacturers to identify and serve, but as individuals that develop their own solutions, therefore becoming users and innovators (i.e. “user-innovators” or “customer-innovators”)20. User-oriented innovation further individuates while also wildly expands the potential for the firm’s innovation search space, as the firm can now experience a rich outpouring of innovation energy from an n(n+1) number of sources across its open, unbounded innovatory ecosystem.

The Strategic Capability of a Values-based Management System

The dynamic capabilities approach to competitive advantage states that the managerial and organisational processes used by a firm – the way that things or done in the firm, or what may be called its “routines,” its patterns of current practice and learning, or its management system – is a source of strategic competitive advantage. These routines strategically and collectively enable management to create and innovate new products and processes and respond to changing market circumstances. They become distinctive if they are based on a collection of routines, skills, and complementary assets that are difficult to imitate19.

We propose that innovation-based organisational values and a values-based management system may serve as a new source of dynamic capabilities for the firm that is competing in the complex innovatory environment created from the growth of need pull innovation, user- and customer-innovation, and the unbounded innovation search space. Research shows that firms that are successful in innovation depend upon two key ingredients: 1) technical resources (such as people, equipment, knowledge, money, and the firm’s embedded organisational and human values); and 2) the values-based capabilities in the organisation to manage the resources6. Values serve as the foundation for developing organisational culture, passion, and shared commitment and the cornerstone for the development and integration of innovation routines, skills, and assets. Studies confirm that the way that people are managed and developed delivers a higher return on investment than new technology, R&D, competitive strategy or quality initiatives, and gives recruitment and retention advantages to those organisations demonstrating flexibility and innovation in their people policies20. Values-based innovation processes that open a firm’s innovation search space may also engender societal level transformation.

The Evolutionary and Innovative Journey of Management Systems

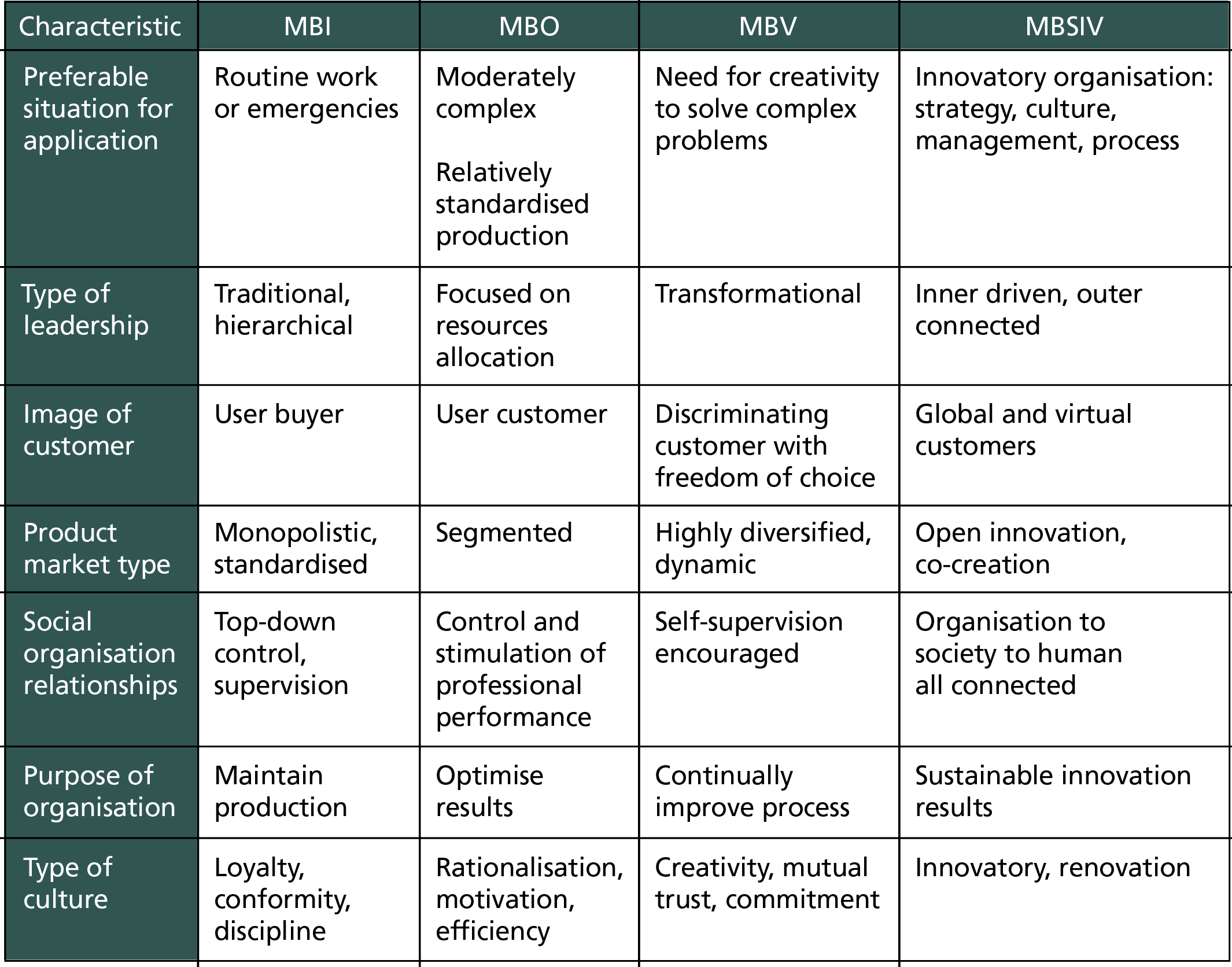

Management systems have evolved, or “creatively destructed,” during the 20th and 21st centuries in correlation with and response to two interrelated forces: increasing levels of organisational and social complexity and increasing needs for organisational, social, and human development. Dolan and Garcia21 have proposed four evolutions of management that each increasingly address sustainability and innovation concerns: MBI, MBO, MBV, and MBSIV.

Initiated in early 20th century, “Management by Instruction” (MBI) recognised that the driving value of firms was efficiency achieved through the implementation of mass production and automation systems.ii With MBI, few people made the key decisions, with employees and customers following their instructions.

With increasing levels of environmental complexity in the middle of the 20th century, MBI was no longer effective. Emphasising both efficiency and effectiveness paradigms, “Management by Objectives” (MBO) emerged. Multiple stakeholders and the attention to legal frameworks and market conditions (yet little to sustainable concerns) ensured that results were accomplished.

“Management by Values” (MBV) emerged at the beginning of the 21st century, a time in which all stakeholders’ activities and needs changed, environmental crises abounded (e.g. climate, water, air, population explosion and terrorism), and the volatility created more awareness across all stakeholders – further exacerbated by higher levels of education of the workforce, the phenomenon of information explosion, instant communication via mobile communication devices, and the fear of nuclear disasters. MBV was used by people who viewed the world more holistically and were more sensitive to the interrelationships of ecology, the social fabric of society, economics, technology, and the search for self-actualisation and self-responsibility22.

Given the increasing levels of transformative forces threatening the survival and sustainability of the world order, this paper proposes that MBV may benefit from reinvention to MBSIV (“Managing by Sustainable Innovation Values”), a next-generation management system that may fuel innovation energy, generate sustainable innovation, optimise performance, and deliver needed solutions to the massive array of human, organisational, and social problems we face today.

Exhibit 1: Comparing the principal characteristics of MBI, MBO, MBV, and MBSIV

Exhibit 1: Comparing the principal characteristics of MBI, MBO, MBV, and MBSIV

From MBV to MBSIV

Previous research has shown that values-based management systems provide a human-centred philosophy and set of practices that enabled leaders to build an organisational culture in alignment with its core organisational goals and strategic objectives. These systems enabled firms to build company-wide commitment to shared values and shared strategies.

The MBV system was born out of understanding how stress impacts people at work. Research shows that psychological “weapons” such as the threat of losing one’s job, the demand for employees to perform as “super people” for prolonged periods of time, and corporate anorexia (cutting the workforce to the bone) has produced the kind and level of toxicity that causes suffering, illness, burnout, and sometimes even death22,iii. Healthy organisations, by contrast were able to develop and maximise individual and organisational well-being23.

Three intersecting 21st century trends are only increasing the level of stress impacting people, organisations, and even societies: 1) the increasing speed of communication and information flows; 2) an increasingly complex context of uncertainties, dualities, and paradoxes; and 3) transformative global forces that threaten the world order: the growing global population; an increasing level of migration and mega cities; a constant search for new ways of creating a decent life; the energy crises; infrastructure collapses; the growing global divide; unequal access to education; and the “metaverse” and singularity of virtual reality24. Well-being is now needed at individual, organisational, and societal levels, its value exponential in measure as leaders face complex global risks that threaten the survival of future generations around the globe.

MBSIV represents a new approach and practice in strategic management that enables leaders to foster human, organisational, and societal wellbeing, health, and wealth through delivering socially-responsible innovation9,20. Managers may use MBSIV to motivate innovation energy: create high-involvement innovation environments, cultures, and climates; build cross-functional, high-performance teams; embed innovation as a core business process; and champion a set of shared values and the will to innovate. (See Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 2: The MBV and MBSIV Models

Exhibit 2: The MBV and MBSIV Models

The MBV Tri-axial Model versus MBSIV Intersectional Model

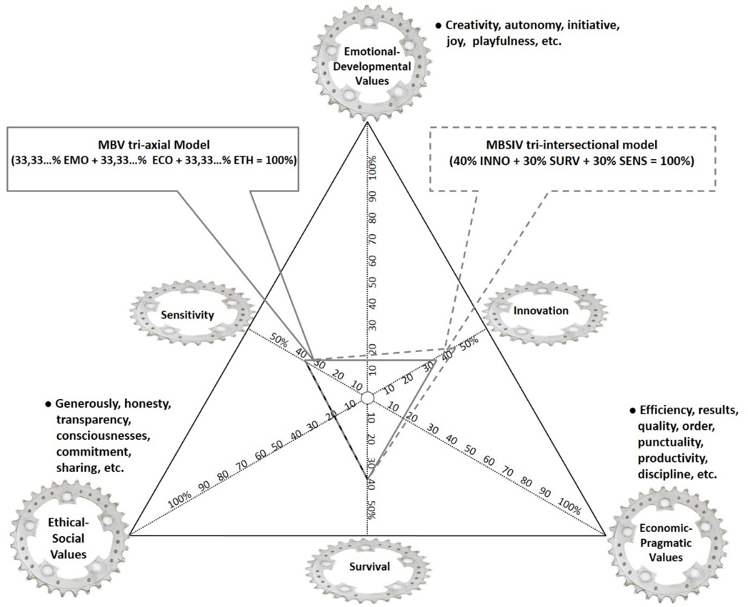

The MBSIV intersectional model of values developed out of the MBV tri-axial model of values, which been used as a tool for developing organisational culture22,23 (See Exhibit 2).

MBV assumes that the central values along with their associated goals and strategic objectives are the foundation for defining a firm’s culture. These values are used by managers and employees to set strategies, make decisions, and guide behaviours, that enable people to do what they do best in their jobs. These three sets of values may be defined and then circumscribed within the triangle that is formed by the following three complementary yet orthogonal axes.

• Economic-pragmatic values are a set of values related to the criteria of efficiency, industrious, performance standards, and discipline. These values guide the planning, quality assurance, and accounting activities in organisations: they are necessary in order to maintain and unify various organisational subsystems.

• Ethical-social values represent the way people behave in groups guided by ethical values shared by members of a group. These values come from conventions or beliefs about how people should behave in public, at work and in their relationships; they are associated with values such as honesty, consistency, respect and loyalty, among others. These values are manifested by actions more than words.

• Emotional-developmental values are essential in creating new opportunities for action. These values are related to intrinsic motivation, which moves people to believe in a cause. Optimism, passion, energy, freedom, and happiness are some examples of these values; without them, people would be unable to make firm commitments or be creative. Therefore, when designing an organisational culture, it is essential that people are able to do what they do best in their jobs.

Firms using MBV as the basis for organisational culture typically develop a symmetric 33-33-33% alignment across the three sets of values. Some will have asymmetry where either the ethical or economic axis dominates, but we argue that this configuration will not necessarily lead to sustainable innovation.

The MBSIV model, on the other hand, is an asymmetrical culture-reengineering model, where explicitly the emotional-developmental axis dominates the culture. The corresponding values serves as a management system for managers of innovative firms to integrate user- and customer-innovators into the innovation business process to achieve sustainable innovation20. MBSIV is typically configured in the proportion of 40% (or higher) emotional-developmental, 30% economic-pragmatic values, and 30% ethical-social values. By averaging these proportional numbers associated with each set of vertices along an axis, an organisation or individual would be able to achieve a 40% focus on innovation, a 30% focus on survival, and a 30% focus on sensitivity. Remember that the emotional-development share of values needs to be greater than the other values in order for the culture to engender the level of innovation energy, or passion, needed for innovation: early research as well as consulting experience shows that true innovation is initiated only when the “innovator” assumes the responsibility to champion a new idea, and that this occurs when passion, or energy, is embedded around and within the innovation process, strategy, and culture – and when roadblocks (i.e. innovation entropy) are reduced.

Managers use MBSIV within the perpetual process of aligning and realigning the three sets of values at their points of intersection, depending on their firm’s strategic goals. Leaders and managers pursuing innovation strategies will develop cultures based upon values associated with the intersection of the emotional-development and economic-pragmatic axes. Those concerned with the survival of the firm will strategically develop cultures based on values defined at the intersection of the economic-pragmatic and ethical-social axes. (After all, when a big ethical or social scandal arises, the survival of the firm is at stake). Those seeking to strategically develop more humane, “sensitive”, and/or socially-responsible firms will develop cultures based on values found at the intersection of the ethical-development and emotional-developmental axes.

The MBSIV model may also be strategically configured to serve as a management coaching when developing employees to achieve innovational goals. The manager/coach would use the MBSIV process to help the employee identify, develop, and use a greater proportion of values skewed towards emotions (the emotional-developmental values) over ethical-social and economic-pragmatic values to achieve innovational goals. The proposed proportion of values in this configuration might be 50% emotional-developmental, 30% economic-pragmatic, and 20% ethical-social. By averaging these proportional numbers associated with each set of vertices along an axis, an individual or organisational would be able to achieve a 40% focus on innovation, a 25% focus on survival, and a 35% focus on sensitivity.

Customer-innovators tend to be more driven by emotional values than the other categories of values. Firms may use MBSIV to determine how to align the value profiles of different innovation stakeholders and ascertain how to involve their input into the innovation business process and embed their contributions into the organisations’ leadership, strategy, goals, and culture.

The Case of Google: A High-Involvement Innovation Environment

Google – voted the top position in Fortune’s Best Places to Work for the 6th year in a row – resembles a firm that has developed a high-involvement innovation environment.

Albeit recent criticism by some Google employees claiming that the organisation has shifted focus from ethics to profits, the level of innovation remains intact. Google’s culture is grounded in sustainable innovation values. Employees are inspired by its mission: “To organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful” and set of “10 things”, or value statements, that were put in place by management at the launch of the business. These “10 things range from statements such as “Focus on the user and all else will follow” to “Great just isn’t good enough.”iv

Google motivates innovation energy and creativity through use of value statements (such as “You can be serious without a suit”), the belief that work should be challenging and challenge should be fun, and an emphasis on team achievements and pride in individual accomplishments contribute to Google’s overall success. They also put great stock in their employees, describing them as “energetic, passionate people from diverse backgrounds with creative approaches to work, play, and life”. They also create a casual atmosphere, which helps inspiring ideas and innovation to emerge from the numerous connections people have, whether in meetings, at the gym, or at the water cooler.v

They have expanded their innovation search space to include user-innovators, freeing people to innovate while avoiding entropy. For example, they use tools such as Google Cafés and Google Moderator internally to encourage interactions across functions and teams. Recognising that innovation needs a lot of “white space” around it20, engineers are invited to spend 20% of their workweek on projects that interest them. User-innovation is also inspired through TGIF weekly meetings; the Google Universal Ticketing Systems (GUTS), which is a way for employees to file issues about anything and that are then reviewed for patterns or problems; ‘FixIts’, which are 24-hour sprints where Google employees drop everything and focus 100 percent of their energy on solving a specific problem; internal innovation reviews, which are formal meetings where executives present innovative product ideas through their divisions to the top executives; organisational surveys; and open, direct email access to any of the company leaders25.

Furthermore, Google’s success has transcended the firm to create societal impact. Not only has the company invested in social entrepreneurs who are working on tech-based solutions for social problems (i.e. access to clean water, wildlife poaching, human trafficking, and poverty)26, their innovations have been said to transform the market, the world, and lives. Google’s technologies have changed peoples language and brains, taken over a majority of the world’s cell phones and email, changed how people collaborate, enabled people to “travel from their desks,” influenced the news, turned users into commodities, and changed how the rest of the world sees every individual27. Google, furthermore, donated over $353 million in grants worldwide, approximately $3 billion in free ads, apps and products, and Googlers have volunteered approximately 6,200 total days of employee time to support non-profits (a total of 150,000 hours) between 2010 and 201326.

Conclusion

Organisations characterised with innovative organisational environments have been found to have the right levels of passion, commitment, and employee engagement that lead to sustainable innovation. However, current research proves the astounding lack of employee engagement that permeates most companies and organisations today. A 2013 Gallup poll found that only 13% of employees worldwide were engaged at work. Very sadly, only one in eight workers – out of roughly 180 million employees studied – were psychologically committed to their job. The reasons cited: frustration, burnout, disillusionment, and misalignment with personal values28. The numbers have changed a bit recently, but huge variation exists between companies and continents. The same Gallup survey shows that engagement in western Europe is one of the lowest (about 10%), while middle East, North Africa, and East Asia is 57% and North America is only at 31%. Obviously, these numbers represent an aggregated data. By contrast, the best companies in the world, reports 70% engagement. The conclusion based on the survey is that engaged employees are 31% more productive, 37% higher in sales, and 13 times more creative and innovative.vi All in all, data suggest that investing in creating an MBSIV culture is really very profitable.

In a world where change is constant and entropy is always a threat, managers and leaders may achieve sustainable innovation by: 1) breaking open their innovation search space by emphasising need pull innovations and harnessing the innovation energy of employees, user- and customer-innovators; 2) developing the strategic dynamic capabilities to lead and manage with sustainable innovation values; and 3) transitioning their management system to Managing by Sustainable Innovation Values (MBSIV). MBSIV is a values-based management system and leadership tool that allows management to develop a values-based, high involvement, performance-oriented innovation culture and deliver sustainable innovation.

[/ms-protect-content]

About the Authors

Dr. Kristine Marin Kawamura is an experienced and success-oriented global consultant, executive coach, scholar/author, educator, and visionary speaker. She is the founder and CEO of Yoomi Consulting Group, Inc. She is also a Visiting Adjunct Professor in Drucker-Ito School of Management in Claremont Graduate University.

Dr. Kristine Marin Kawamura is an experienced and success-oriented global consultant, executive coach, scholar/author, educator, and visionary speaker. She is the founder and CEO of Yoomi Consulting Group, Inc. She is also a Visiting Adjunct Professor in Drucker-Ito School of Management in Claremont Graduate University.

Dr. Simon L. Dolan is currently the president of the Global Future of Work Foundation (www.globalfutureofwork.com). He used to be the Future of Work Chair at ESADE Business School in Barcelona, and before that he taught for many years at McGill and Montreal Universities (Canada), Boston and University of Colorado (U.S.). He is a prolific author with over 70 books on themes connected with managing people, culture reengineering, values and coaching. His full c.v. can be seen at: www.simondolan.com

Dr. Simon L. Dolan is currently the president of the Global Future of Work Foundation (www.globalfutureofwork.com). He used to be the Future of Work Chair at ESADE Business School in Barcelona, and before that he taught for many years at McGill and Montreal Universities (Canada), Boston and University of Colorado (U.S.). He is a prolific author with over 70 books on themes connected with managing people, culture reengineering, values and coaching. His full c.v. can be seen at: www.simondolan.com

References

i. See http://web.mit.edu/16.unified/www/FALL/thermodynamics/notes/node49.html.

ii. See Dolan and Garcia (2002); Earley, P. C. & Gibson, C. B. 2002. Multinational Teams: New Perspectives, Mahwah, NJ, Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. and Dolan et al. (2006).

iii. Dolan S.L.(2006) Stress, Self-Esteem, Health and Work. Palgrave MacMillan.

iv. See http://www.google.com/about/company/philosophy/

v. See What every company can learn from Google´s company culture

https://www.successagency.com/growth/2017/01/19/google-company-culture/

vi.See the survey of Gallup for 2017 at: http://news.socialreacher.com/en/the-12-questions-from-the-gallup-q12-employee-engagement-survey/

1.Diamond, J. M. (1999). Guns, Germs, and Steel, New York, W.W. Norton & Co.

2.World Economic Forum. (2015). Global Risks 2015, 10th edition [Online]. Geneva, Switzerland. Available: http://reports.weforum.org/global-risks-2015/ [Accessed March 1 2016].

3.Dutton, J. (2003). Energize Your Workplace, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

4.Pascarella, P. (1989). The Purpose-Driven Organization: Unleashing the Power of Direction and Commitment, San Francisco, CA, Jossey Bass.

5.Badaracco, J. L., Jr. & Ellsworth, R. R. (1989). Leadership and the Quest for Integrity, Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

6.Knowles, R. N. (2009). Engaging the natural tendency of self-organization. In: WIRTENBERG, J., RUSSELL, W. G. & LIPSKY, D. (eds.) The Sustainable Enterprise Fieldbook. UK: Greenleaf.

7. McKinsey Quarterly (2015) Marc de Jong, Nathan Marston and Erik Roth “The eight essentials of innovation”, April.https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-eight-essentials-of-innovation

8.Tidd, J. & Bessant, J. (2013). Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change, 5th edition, West Sussex, UK, Wiley.

9.Brillo, J., Dolan, S. L. & Kawamura, K. (2014). Portraying the Case of the 40-30-30 Tri-Intersectional Model. ESADE Business School Research Paper, No. 259.

10.Dolan, S. L., Brillo, J. & Kawamura, K. 2014. Coaching by Sustainable Innovational Values (CSIV): The 40-30-30 tri-axial intersectional model of values. Effective Executive. , Dec, XVII, 7-14.

11.Lewis, K. & Lytton, S. (2000). How to Transform Your Company, London, Management Books.

12.Denti, L. & Hemlink, S. (2012). Leadership and innovation in organizations: A systematic review of factors that mediate or moderate the relationship. International Journal of Innovation Management, 16, 1-20.

13. Francis, D., and Bessant, J. (2005) Developing routines for managing discontinuous innovation In: EURAM 2005, 4-7 May 2005, Munich, Germany

14.Stalk, J. G., Pecaut, D. K. & Burnett, B. (1996). Breakaway Compromises, Breakaway Growth. Harvard Business Review, Sept-Oct, 129-140.

15.Kim, W. C. & Mauborgne, R. A. (2015). Blue Ocean Strategy, Expanded Edition: How to Create Uncontested market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant, Boston, Harvard Business Press Books.

16.Christensen, C. M., Grossman, J. H., M.D., & Hwang, J., M.D. (2008). The Innovator’s Prescription: A Disruptive Solution for Health Care, New York, McGraw-Hill.

17. Raich M., Eisler R., Dolan S.L. (2014) Cyberness: The Future Reinvented, Createspace Independent Publishing Platform (Amazon)

18. Von Hippel E. (2005) Democratizing Innovation. MIT press (http://web.mit.edu/evhippel/www/books/DI/DemocInn.pdf)

19.Teece, T. & Pisano, G. (1994). The Dynamic Capabilities of Firms: an Introduction. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3, 537-556.

20. Brillo, J., Dolan, S. L., Kawamura, K. & Fernández-Marín, X. (2015). Managing by Sustainable Innovational Values (MSIV): An asymmetrical culture reengineering model of values embedding user innovators and user entrepreneurs. Journal of Management and Sustainability, 5, pp. 1-13. DOI: 10.5539/jms.v5n3p.

21. Dolan S.L. Garcia S., (2002) Managing by values: Cultural redesign for strategic organizational change at the dawn of the twenty-first century, Journal of Management Development, Volume 21, Issue 2

22. Dolan S.L., (2011) Coaching by Values. Bloomington – iUniverse. Raich M., Eisler R., Dolan S.L. (2014) Cyberness: The Future Reinvented, Createspace Independent Publishing Platform (Amazon)

23.Dolan, S. L., Garcia, S. & Richley, B. (2006). Managing by Values: A Corporate Guide to Living, Being Alive, and Making a Living in the 21st Century, New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

24. Raich M., and Dolan S.L. (2008) Beyond: Business and Society in Transformation (Palgrave-MacMillan)

25.He, L. (2013). Google’s Secretions of Innovation: Empowering it’s Employees. Forbes [Online]. Available: http://www.forbes.com/sites/laurahe/2013/03/29/goo gles-secrets-of-innovation-empowering-its-employees/ [Accessed June 29, 2015].

26.Smith, J. (2013). The Companies With the Best CSR Reputations. Forbes [Online]. Available: http://www.forbes.com/sites/jacquelynsmith/2013/10/02/the-companies-with-the-best-csr-reputations-2/ [Accessed June 29, 2015].

27.Poppick, S. (2014). 10 Ways Google Has Changed the World. Money [Online]. Available:http://time.com/money/3117377/google-10-ways-changed-world/[Accessed June 29, 2015].

28. HBR report (2015) The impact of employee engagement on performance.https: //hbr.org/resources/pdfs/comm/achievers/hbr_achievers_report_sep13.pdf