By Stijn Viaene

Customer-centric practices have been one of the key considerations in this age of digital transformation. In this article, Professor Stijn Viaene elaborates on how customer experience as value must be prioritised and how the concept can drive an organisation to its success.

The digital economy has put customers firmly in the driving seat. Freely roaming around the Internet, triggered by popups or alerts and assisted by Internet bots, customers are switching between different sites, between their laptops and their mobile apps, combining online searching with offline buying and vice versa, as the boundaries between the online and offline are increasingly blurred. Customers want, and digital allows them, to take control over their lives’ journeys.

Products and services are no longer enough to win over or keep customers in the digital era. The digital space is notorious for how fast it commoditises products and services. Ultimately, value is attributed to the total experience of engaging with customers in ways that fit with their modern connected, mobile and social lives. Making your organisation’s digital transformation work,1 will require a radical shift from taking an inside-out, company-centric product perspective to taking an outside-in, customer-centric experience perspective for creating customer value.2 Sounds simple? Think again. In this article, I summarise what any leader should know about the first reality of competing in the digital world: customer experience is value.

The New Normal: Access and Convenience

Some 20 years ago, inspired by the rise of the Internet 1.0, Joseph Pine and James Gilmore oracled the arrival of the so-called experience economy.3 Experiences, they argued, are a source of economic value, just like commodities, products and services, but they are distinctly different. Experiences are positioned as the next step in a historical progression of definition of value. Experiences are personal, intense – especially in consumer businesses, and represent a customer response that says: you really get me!

Many leaders did not see it then. Now, we have Uber, Airbnb and Lending Club to highlight the profound impact of today’s democratised access to digital technologies on customer expectations.

Uber is a speaking example of a broader digitisation phenomenon that is setting a new normal for customer value based on ease of access, convenience and cost efficiency beyond anything pre-digital companies can offer.

But are these value drivers the definition of customer experience? I don’t think so. Granted, in most industries the amount of transactional friction that digital allows us to cut is massive, and so are the customer value improvement opportunities. However, thanks to digital disruptors, convenience, access and cost drivers are rapidly becoming hygiene factors, rather than true delighters. Although terribly important as competitive necessity, these value dimensions per se should not be mistaken for what makes a product into a truly valuable customer experience.

Again, Uber is a thankful example to drive home a most important observation linked to digitisation and the nature of value: customers no longer have to buy cars, they can now enjoy mobility. The same principle applies to apartments (Airbnb), or say, work: companies don’t want employees, they want jobs to be done. Like your customers don’t want products, they just want a job to be done. Once you get this, you will want to design great new customer experiences rooted in a unique interplay between digital and physical. You’ll understand you’ll have to turn around the way you design, deliver and capture customer value. That means thinking differently: like a designer.

Design for an Experience Economy

The connection between product innovation and designer methods goes a long way back. With the focus now more than ever on creating great customer experiences rather than just products, design has penetrated the core of the business. “Think like a designer” has become a buzz phrase not just in Silicon Valley but all over the digital world.

Design thinking can best be described as a principle-based problem solving discipline that forces businesses to fundamentally rethink value propositions and the nature of work. Its principles pertain to the way customer value – experience – is defined as well as the way problems are solved. There is one underlying meta-principle: the acceptance that the world we live in is not static or linear, but rather is a dynamic and complex system. Instead of shying away from that volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) environment, design thinkers embrace it in an ambition to create more rich and fitting customer solutions.

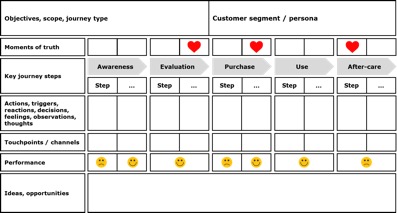

Empathy Principle. The empathy principle is the hallmark of design thinking. It states that great design is ultimately rooted in empathic, rich, holistic understanding of human needs. Design thinkers refrain from jumping to solutions. They first spend ample time and effort to absorb the world from the point of view of the customer. They open themselves up to the whole person and try to unfold the complexities of a customer’s emotions and desires (the heart), intentions (the head), and behaviours (the hands) in a particular context. Design thinkers acquire a profound appreciation for the detailed context in which a particular customer need appears. A popular template for painting that context is the customer journey map (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Example Customer Journey Mapping Template

Show-it Principle. Design thinkers resort to visual thinking to gain access to the experience space. Visual models, like customer journey maps, allow them to involve a diversity of stakeholders in holistic, multi-faceted problem solving, capture the full richness of situations and experiences, and tell appealing stories. Concept tests and prototypes are promoted to show value at work early and often during the design process. Design thinkers operationalise the concept of customer experience as the customer’s reaction to what she sees, what she feels, what she senses and interprets when being exposed to (a model of) the value design at work. Design thinkers seek feedback – rather than appreciation, which makes design thinking co-creative by default.

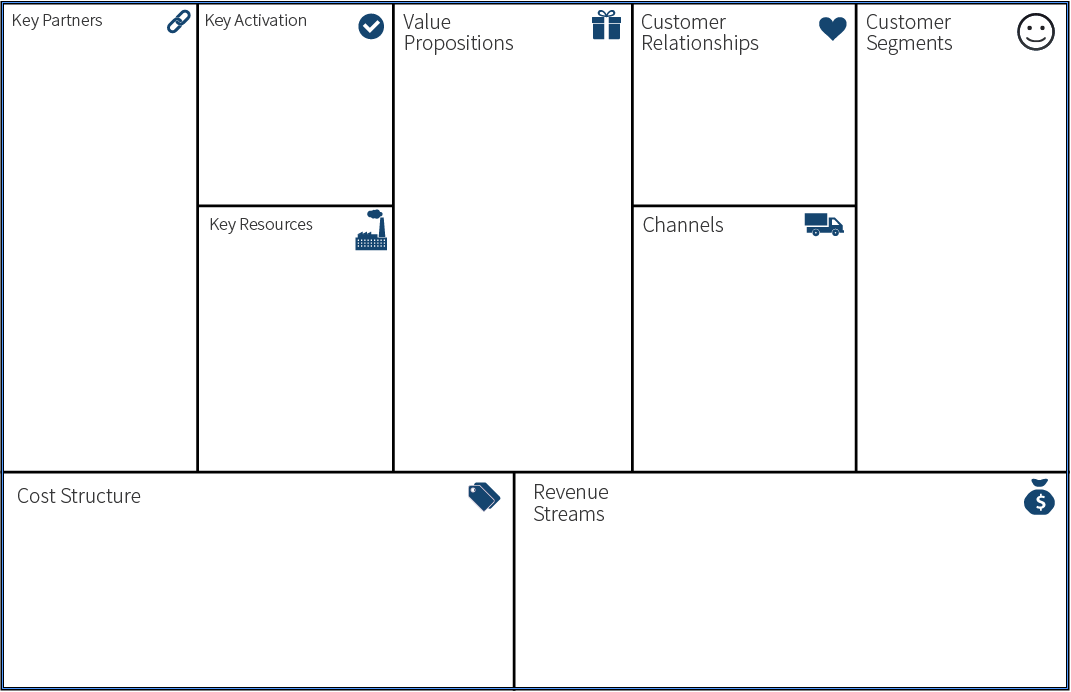

Create-capture Principle. Design thinking is not about creating beautiful artefacts. Design thinkers aspire to create solutions that represent value for the customer, but also allow a business to capture that value. The solutions design thinkers go after, ideally, combine customer desirability, technical and organisational feasibility and business viability. At every stage of the problem solving process, design thinkers work to produce value that satisfies these three performance dimensions.

For example, Alex Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur’s business model canvas is a one-page visual schematic that is widely used to broaden the perspective on value design to include the business dimension (see Figure 2).4 The canvas allows to concisely describe, design and challenge a business model’s desirability (customer-facing; right side of the canvas), feasibility (activity-related; left side) and viability (profit formula; bottom part) hypotheses.

Figure 2: Business Model Canvas Template

(strategyzer.com)

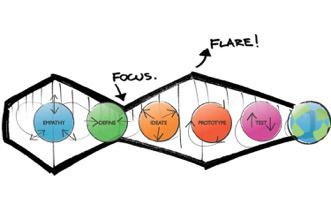

Diverge-converge Principle. Design thinkers rely on a problem solving process that uses a sequence of divergent thinking – open up, creatively generate options, hypotheses and choices – and convergent thinking – narrow down, choose options, hypotheses and make choices – in both the problem and solution identification stage of the design process. This logic is illustrated in Figure 3 for the particular case of Stanford d-school’s 5 step design thinking process variant. Divergent thinking promotes an open-minded, creative problem solving culture, invites taking perspectives that look at the whole customer experience, and are forward looking. It also stimulates search beyond the traditional domains, recognising, for example, that adjacent domains may have already solved a problem similar to the one you are trying to solve. In many cases, it is smarter to borrow or reuse than to reinvent.

Still, scope creep and analysis paralysis are important risks of stimulating divergence. These issues can be addressed by deploying two key process governance tactics: (1) imposing a swift and steady, predictable pace on the sequence of diverge and converge steps in the design thinking process; and (2) putting a cap on the available resources upfront, thus minimising the possible loss (downside risk). These tactics keep the process manageable and result oriented.

Figure 3: D-School’s Design Thinking Process

(dschool.stanford.edu)

Iterate-learn Principle. Design thinkers may be ambitious and result oriented, they also remain humble in their search for great solutions. For them, the world is simply too complex and dynamic to expect value designs to be first-time right. Indeed, it typically takes multiple iterations of design for all but the simplest issues to converge on a satisfactory solution. Moreover, the path to satisfaction may involve failure at any point, requiring the designer to pick up the pieces and choose an alternative route. Failure is regarded as a natural part of the game, accepted, as long as it gets the designer closer to a result. When they fail, they fail smart.

Infusing critical thinking into a steadily paced progression of design iterations allows design thinkers to be smart: staying focused and maximising the learning with every iteration. This objective is achieved by keeping designers conscious of the critical assumptions they make about what is a valuable solution. The process will ask them to make their key design choices – hypotheses – explicit, so that prototypes can be geared at gathering feedback to test these critical hypotheses. A design pivot is what will be required if a design’s most important hypotheses are invalidated. Pushing designers to be explicit about key design choices keeps them mindful of the biases they may have about what constitutes customer value. This way, customer value is not assumed, but validated.

Collaborate Principle. To come to full fruition, design thinking requires different types of thinkers, stakeholders and functions to work closely together as a team to create desirable, feasible and viable customer experiences. Investing in boundary-spanning teamwork to productively gather all value perspectives around a common process and principles is critical for design thinking to work. Just like design thinkers aim to empathise with their customer, team members will have to be able to understand, let in and trust one another.

The Digital Edge in Design

Digital technologies have given a significant boost to design thinking, as in their application lies a tremendous opportunity for enacting the discipline’s principles of customer centric value design to reimagine the very foundation of business. There are multiple interconnected angles to using digital technologies for rethinking customer experiences:

Automation: digitising, streamlining customer journeys and business processes by connecting information and eliminating wasteful manual labour, paperwork and complexity to make customer experiences easy, convenient and cost-effective. For example, reducing a complex payment process to a one-click payment, routing emails automatically by applying a set of business rules inferred from big data, or using a blockchain to eliminate costly middle men.5

Customisation/Personalisation: using data gathered from automation and other internal and external data sources to customise or personalise experience along a particular customer’s journey in real time. For example, using a recommendation engine to suggest the best next movie based on your preferences and tracked behaviour, allowing your kid to co-create his/her next Lego purchase using a toy design app, or using smart connected energy grid substation data to customise preventive asset maintenance services.

Socialisation: infusing social media data and adding social connectivity into customer journeys to enable or enrich customer experiences. For example, enabling job seekers to connect with trusted mentors in the sector of their dreams using a tinder-like mechanism, allowing customers to vote for innovative ideas using your company’s Facebook group, or using an immersive virtual reality environment to augment value co-creation with customers and partners.

Contextualisation: using data pertaining to the actual digital and/or physical whereabouts of a particular customer travelling a journey to increase customer relevance and intimacy. For example, using intelligent second screen technology showing e-commerce opportunities detected from watched televised content in real-time, crowdsourcing real-time traffic information for suggesting the best alternative driving route for you at this very moment, or automatically adapting the format of a promotional message to a type of user device.

Designing: in addition to exploring the potential of digital technologies for particular solutions and customer journeys, digitisation also benefits the design thinking process itself. For example, using rapid UI mock-up apps to swiftly validate concepts, automating customer measurement, massively running online experiments (e.g. A/B testing), or deploying artificial intelligence to autonomously learn how to improve experience design.

A fruitful way to help generate automation, digital personalisation, socialisation and contextualisation ideas for improving customer experience is to target key customer journey pain points or moments of truth identified from applying empathy. Don’t forget, however: it’s the journey that eventually makes the difference, not an individual digital intervention or point solution. Always consider the impact on the customer journey end-to-end.

More Than Skin Deep

Many companies have made the mistake of creating apps – even very empathic ones – at the expense of a consistent, integrated customer experience across channels (digital and physical). Some have created real app jungles, in which their customers, and employees, get completely lost. Others have activated all possible digital channels (websites, mobile apps, email, twitter, Facebook, etc.), but failed to recognise a customer as one and the same across these channels. That, of course, is not customer centric. These inconsistencies quickly erode customer loyalty and brand.

The lesson: don’t confine customer experience design to organisational silos. True customer centricity requires taking a comprehensive organisational view, aligning incentives, business processes and structures. If you want your customer focus to be effective and lasting, you need boundary-spanning coordination and collaboration across functions and channels. Great on-stage touchpoint engagement is built on the foundation of equally great behind-the-scenes business processes, end-to-end configurations of activities that together create value for the customer.

On the surface, business process management (BPM)6 and digital transformation sound like a match made in heaven. Unfortunately, many don’t see it that way. They’d rather avoid inviting BPM to the digital party, for a number of reasons.

First, existing BPM initiatives all too often did not live up to their promises: they lost their focus on the customer, emphasised cost cutting rather than customer improvements, were confined to single departments or back-office processes rather than enterprise-wide, or focussed on technology solutions rather than holistic work redesign. Second, most BPM efforts were never designed to optimise business processes against the backdrop of a VUCA world, a business context that requires constant innovation and end-to-end agility. They targetted cost, efficiency and reduction of variation, rather than speed-to-market, flexibility and variety. Third, in their attempts to make sense of the digital age, many existing organisations were blind sighted by what digital start-ups seemed to be doing. At first blush, they didn’t seem to need BPM.

Successful scale-ups, however, rely on a smart combination of design thinking and BPM. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos coined this into a leadership lesson: “We start with what the customer needs and we work backwards.”7 Design thinking and customer journeys allow the company to start with a premise of being “customer obsessed”. Adding a business process lens – in the case of Amazon applying lean process management principles – allows them to subsequently work backwards to streamline experience creation end-to-end, as an activity process cutting through silos, beyond the line of visibility.

Indeed, leaders digitise customer journeys as well business processes. But they digitise their business processes in function of a holistic, empathic customer experience. Business processes are reimagined for customer jobs to be done and customer journey maps end-to-end. The VUCA reality, however, forces the BPM discipline to enable agility as much as operational efficiency. That is a serious transformation challenge for the BPM field, but a challenge to be faced because there is a real need for addressing process change that cannot be addressed with a mere focus on customer journey design.

The first critical requirement for BPM to be able to reclaim its rightful position at the digital transformation table is to make design thinking principles and customer journey mapping its starting point. Moreover, as a change discipline, it needs to be capable of marrying customer empathy and business benefits with the employee perspective and empathy, for unhappy employees make for unhappy customers.

Two requirements stand out for BPM on the technological side: enabling convenient and consistent information access across silos for coordinating process activities end-to-end, and offering a capability to compose business processes on the spot based on customer and business event data or analytics triggers. Without these technology affordances, your business won’t be capable of effectively personalising and contextualising end-to-end customer journey experiences in real-time.

Conclusion

Today’s competition revolves around customer experience, a non-trivial value concept. Design thinking offers a very useful lens for acting your way into a new way of “experience is value” thinking. If its application stays confined to an organisational silo, however, the effect will be marginal at best, but most likely counter-productive. For digital transformation purposes, the advice is to connect design thinking with BPM, understanding that establishing this connection will very likely require the BPM discipline to transform itself.

About the Author

Stijn Viaene is a Full Professor and Partner at Vlerick Business School in Belgium. He is the Director of the school’s Digital Transformation strategic focus area. He is also a Professor in the Decision Sciences and Information Management Department at KU Leuven.

Stijn Viaene is a Full Professor and Partner at Vlerick Business School in Belgium. He is the Director of the school’s Digital Transformation strategic focus area. He is also a Professor in the Decision Sciences and Information Management Department at KU Leuven.

Notes

1. Digital transformation was defined as “a form of end-to-end, integrated business transformation where digital technologies play a dominant role” in Viaene, S. (2017). What Digital Leadership Does. The European Business Review, May-June.

2. Understanding the four realities driving competition in the digital age was considered a mandatory starting point for any successful digital transformation in Viaene, S. (2017). Rethinking Strategy for the Digital Age: An Executive Primer. The European Business Review, July-August. In this article we elaborate on the first reality: customer experience is value.

3. Pine, J. & Gilmore, J. (1999). The Experience Economy. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

4. Osterwalder, A. & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers and Challengers. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons.

5. A blockchain is a database technology that makes it possible to create a digital ledger of transactions and share it among a distributed network of computers. It uses cryptography to allow each participant on the network to manipulate the ledger in a secure way without the need for a central authority to guarantee the veracity of transactions. Blockchain technology uses security by design to eliminate trusted third-parties or middle men from digital transactions.

6. vom Brocke, J., Schmiedel, T., Recker, J., Trkman, P., Mertens, W. & Viaene, S. (2014). Ten Principles of Good Business Process Management. Business Process Management Journal. 20(4).

7. Anders, G. (2012). Jeff Bezos’s Top 10 Leadership Lessons. Forbes. April 23.