By Adrian Furnham

Many of us, at one time or another, may have thought, “One day, they’re going to see through me.” If you’re one of them, perhaps improving your self-evaluation skills could come in handy, as Adrian Furnham describes.

The Impostor Syndrome describes high-achieving individuals in any area of endeavour, from business to sport, who, despite their objective successes, do not accept and internalize their accomplishments. They have persistent self-doubt and fear of being exposed as a fraud or impostor, somehow not deserving of their success. They might sabotage, consciously or unconsciously, their performance, hence confirming their self-appraisal. The concept has been around for over 40 years and is much discussed when clearly brilliant people “go off the rails” at the peak of their success.

Studies on the Impostor Syndrome

A recent review found that the syndrome was relatively common among both men and women and across a range of age groups (adolescents to late-stage professionals). Also, it is often comorbid with depression and anxiety and is associated with reduced job performance, job dissatisfaction, and burnout. In short, talented people can underachieve because of their erroneous self-beliefs.

Typical “symptoms” include self-doubt, an inability to realistically assess personal competence and skills, attributing personal success to external factors, berating and being hyper-critical about personal performance, fear of not living up to expectations, a sense of overachievement, sabotaging personal success, and setting very challenging, almost impossible, goals and feeling disappointed when they are not achieved.

People with Impostor Syndrome struggle with accurately attributing their performance to their actual competence. They attribute successes to external factors such as luck or receiving help from others.

Essentially, people with Impostor Syndrome struggle with accurately attributing their performance to their actual competence. They attribute successes to external factors such as luck or receiving help from others and attribute setbacks as evidence of their professional inadequacy. Research has moved beyond early studies with high-achieving white women. It is now linked to multiple academic fields (mental health, sport, and STEM), antecedents (e.g., perfectionism and discrimination), outcomes (e.g., career burnout and depression), and many populations (e.g., men and racial minorities).

The Impostor Syndrome describes an individual’s experience of intellectual phoniness and fear of exposure – people who are clearly competent and talented, yet for some reason cannot accept their success. Rather than acknowledging their effort and competency, they believe their success was due to luck or favoritism. They discount their intellectual or physical capabilities, attributing their success to external factors (e.g., luck) which in time will eventually be discovered. Early researchers suggested a clear cycle: first, worrying that others will expose their self-perceived incompetence, then imposing high expectations and performance standards on themselves, which in turn demand excessive effort and energy.

There are standard tests to measure the syndrome. They include questions such as: Do you agonize over even the smallest mistakes or flaws in your work? Do you attribute your success to luck or outside factors?

These are 10 items from a well-known test:

- I have often succeeded on a test or task even though I was afraid that I would not do well before I undertook the task.

- I can give the impression that I’m more competent than I really am.

- I avoid evaluations if possible and have a dread of others evaluating me.

- When people praise me for something I’ve accomplished, I’m afraid I won’t be able to live up to their expectations of me in the future.

- I sometimes think I obtained my present position or gained my present success because I happened to be in the right place at the right time or knew the right people.

- I’m afraid people important to me may find out that I’m not as capable as they think I am.

- I tend to remember the incidents in which I have

not done my best more than those times I have

done my best. - I rarely do a project or task as well as I’d like to do it.

- Sometimes I feel or believe that my success in my life or in my job has been the result of some kind of error.

- It’s hard for me to accept compliments or praise about my intelligence or accomplishments.

According to leading expert Valerie Young, people who feel like impostors hold themselves to unrealistic, unsustainable standards of competence. Through her work with tens of thousands of people from a wide range of occupations and levels, five distinct competence types emerged each with its own unique focus.

- The perfectionist: The primary focus is on “how” something is done, how the work is conducted, and how it turns out. One minor flaw in an otherwise stellar performance or 99 out of 100 equals failure.

- The expert: As the knowledge version of the perfectionist their primary concern is “what” and “how much” they know. Because they expect to know everything, even a minor lack of knowledge makes them feel less competent.

- The soloist: They care mostly about “who” completes the task. Because they think they should be able to succeed entirely on their own, needing help, tutoring, or coaching is a sign of incompetence.

- The natural genius: They also care about “how” and “when” accomplishments happen. But for them, competence is measured in terms of ease and speed. If they have to struggle to understand or to master a skill or success does not happen on the first try, makes them feel less competent.

- The superhuman: Measures their competence based on their ability to excel across skill sets and roles, e.g., scientific discovery and leadership, big picture strategic planning and detailed execution. For some this includes the expectation that they are the best at parenting, sports, or other activities. Falling short in any role can evoke shame because they think they should be great at everything they do.

There are many suggestions for dealing with the Impostor Syndrome. These include ideas such as “Confront your Inner Critic” and dispel the “Whispering-Monkey-on-the-Shoulder”. Clearly this means attempting to refute the false narrative about yourself by comparing self-perceptions with some objective reality. Young maintains that since feelings are the last to change, instead of attempting to “fix” yourself that you change your thinking about competence instead. Other recommendations such as “Change your Personal Narrative” “Increase your Self-Awareness”, and replace rumination with reflection are essentially the same. The aim is to get some explicit and objective comparison between personal beliefs and the “actual” state of affairs.

Other suggestions include “Celebrating Success” in the sense that people should recognise and celebrate every time they are successful in a particular endeavour.

Fear of Success

Martina Horner over 50 years ago described the concept of Fear of Success when she studied stereotypes and biases that were discouraging women from pursuing a career in medicine, at a time when fewer than 10 per cent of doctors were female. She argued that women had “a motive to avoid success or a ‘fear of success’” because they feared the negative consequences of succeeding in traditionally male domains. This included a loss of femininity, self-esteem, and social identity.

These women saw having successful personal relationships as a great success, but having a professional job less so. The conclusion from this early work was that women needed to exhibit the masculine trait of competitiveness if they wanted to succeed. Hence they feared rejection, thus inhibiting aspirations, capabilities, and performance, which in turn affects the potential for women to develop a career. Moreover, if women did succeed, this was not seen to be due to their ability and effort, but luck or some other reason.

The same idea has been applied to social class, suggesting that individuals from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds fear that success will lead to alienation from their community, the loss of identity, and loss of the overall sense of belonging within their culture.

These are the types of self-beliefs that early studies on fear of success considered: Often the cost of success is greater than the reward; for every winner there are several rejected and unhappy losers; it is more important to play the game than to win it; in my attempt to do better than others, I realize I may lose many of my friends; a person who is at the top faces nothing but a constant struggle to stay there; I think “success” has been emphasized too much in our culture; in order to achieve, one must give up the fun things in life; the cost of success is overwhelming responsibility.

Perfectionism

There is a well-established “dark side” to perfectionism. It is associated with depression and many health issues, such as suicide and eating disorders. Hence it is linked to obsessive and compulsive disorders, eating disorders, substance abuse, and “workaholism”.

It has been observed that the Impostor Syndrome has been closely linked to perfectionism, which is a trait that can influence all aspects of life. It is possible to see these on a dimension, variously labelled active and passive perfectionism, positive and negative perfectionism, and adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism. Clearly, setting high standards and achieving them in many aspects of life is often very desirable and takes much effort. However there is a well-established “dark side” to perfectionism. It is associated with depression and many health issues, such as suicide and eating disorders. Hence it is linked to obsessive and compulsive disorders, eating disorders, substance abuse, and “workaholism”. It is usually treated by quite different approaches.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) aims to help perfectionists in reducing social anxiety, public self-consciousness, etc. Next comes dynamic-relational therapy, which concentrates on the maladaptive relational patterns and interpersonal dynamics underlying and maintaining perfectionism. Others include Acceptance-based Behavior Therapy.

Hubris vs Humility

The Dunning–Kruger Effect is a form of overconfidence in which people with limited competence in a particular domain overestimate their abilities; people with low ability are unaware of their comparative score. It is essentially about false assessment; they are biased in their assessment for various reasons, from laziness to an inability to calibrate correctly. In short, many believe they are talented when they are not. They are not bright enough to know how dim they are.

Overconfidence is a judgemental error in which individuals overestimate their performance accurately. It has been linked to deficiencies in decision-making and risky behavior. It is possible to differentiate between three facets of overconfidence: 1) over-placement; 2) over-estimation; and 3) over-precision. Over-placement occurs when an individual possesses a positively biased self-view in relation to others. Over-estimation refers to inflated self-view of a person’s ability level or performance. Over-precision results when an individual has exaggerated confidence concerning the accuracy of their beliefs.

The Impostor Syndrome is the exact opposite, where people with a range of abilities (and proven successes) underestimate their talents.

The Psychology of Self-Estimated Intelligence

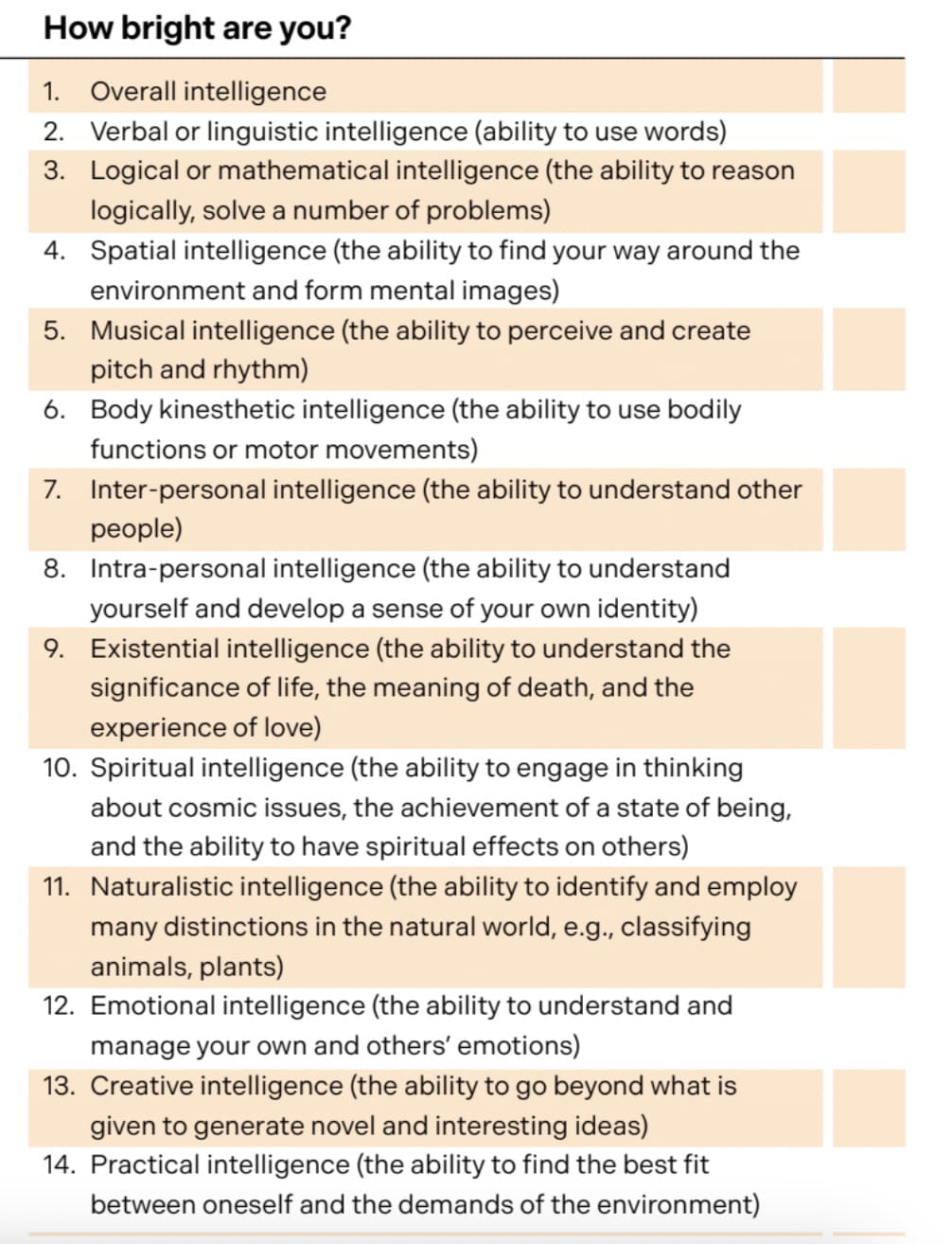

I have worked in this area for some time. The idea is simple: do people know how bright they are? One way of assessing this is to compare their self-assessed intelligence with their scores on thorough and validated IQ tests. This can be done with overall IQ or very specific multiple intelligences. So people can dramatically underestimate their score, manifesting humility, or overestimate their score, manifesting hubris.

It is not known who said, “Whether you believe you can do a thing or not, you are right,” which suggests the powers of your self-estimates.

See below how these ideas are tested

How Intelligent Are You?

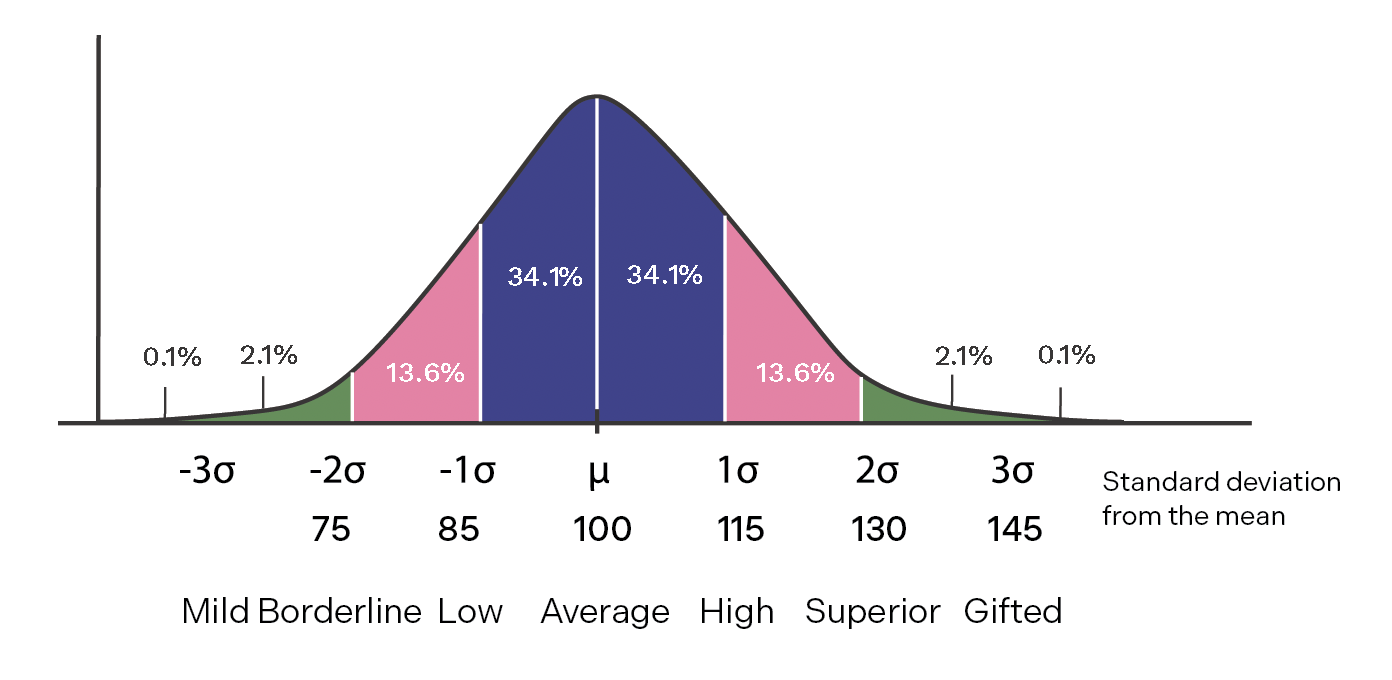

IQ tests measure a person’s intelligence. The average or the mean score on these tests is 100. Most of the population (about two-thirds of people) score between 85 and 115. Very bright people score around 130, and scores have been known to go over 145. The graph below shows a typical distribution of these scores.

But there are different types of intelligence. We want you to estimate your overall IQ and your score on 14 basic types of intelligence. Give your estimated score (e.g., 110, 105, 95, 120) for each of these.

The results of the research in this area can be summarized thus:

First, males of all ages and backgrounds tend to estimate their (overall) general intelligence to be 5 to 15 IQ points higher than do females. Always those estimates are above average and usually around one standard deviation (15 points) above the norm.

Second, when judging “multiple intelligences”, males estimate their spatial and mathematical (numerical) intelligence higher, but emotional intelligence lower than do females. On some multiple intelligences (verbal, musical, body-kinesthetic), there is little or no sex difference.

Third, people believe these sex differences occur across the generations: people believe their grandfather was/is more intelligent than their grandmother, their father more intelligent than their mother, their brothers more intelligent than their sisters, and their sons more intelligent than their daughters. That is, throughout the generations in one’s family, males are judged more intelligent than females.

Fourth, sex differences are cross-culturally consistent. While African men tend to give relatively higher estimates, and Asian men relatively lower estimates, there remains a sex difference across all cultures. Differences seem to lie in cultural definitions of intelligence, as well as norms associated with humility and hubris.

Fifth, the correlation between self-estimated and test-generated IQ is positive yet low (in the range of r=.2 to r=.5), suggesting that you cannot use self-estimated test scores as proxy for actual scores.

Sixth, with regard to outliers, those who score high on test-generated IQ, but who give low self-estimates, tend nearly always to be female, while those with the opposite pattern (high estimates, low scores) tend to be male.

Seventh, most people say they do not think there are sex differences in intelligence.

So: Both the Impostor Syndrome and the Dunning-Kruger Effect are the consequence of poor insight into personal abilities and strengths. One solution lies in sustaining rigorous, consistent, and accurate feedback on personal strengths and weaknesses, and then finding a way to address any issues. It is very sad to see highly talented people not exploring and exploiting their talents. Equally, it is surprising how less-talented and deluded people can convince others, as well as themselves, about their actual abilities.