By Fernanda Arreola, Nora Guessoum, and Elizabeth Walker

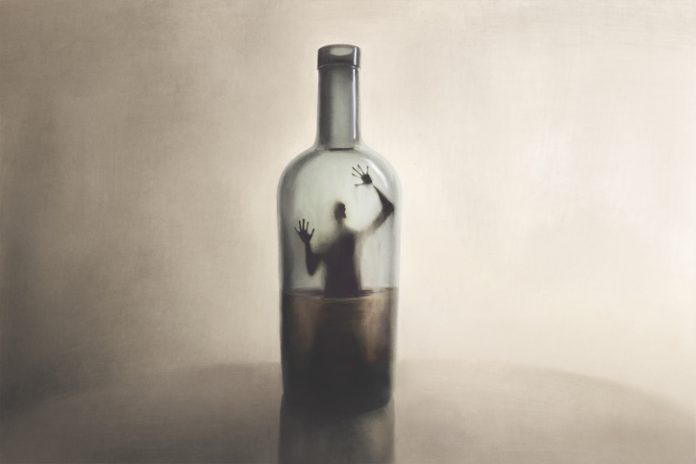

Addiction often hides in plain sight, crossing social, professional, and cultural boundaries with ease. In this article, Fernanda Arreola, Nora Guessoum, and Elizabeth Walker invite reflection on how silence, stigma, and misunderstanding sustain addiction, and why open conversation, compassion, and connection are essential for meaningful prevention and recovery.

The Elephant in the Room

Addiction isn’t something that happens to “other people.” It isn’t confined to dark alleys, broken homes, or the sensationalized stories splashed across the tabloids. It’s present in boardrooms, classrooms, hospitals, and households across the globe. Gender, occupation, and social status were thought to be limiting environments for an addiction to install itself. However, recent research invites us to consider that addiction concerns us all, and chances are you already know someone who’s quietly struggling.

Still, “being an addict” remains one of the heaviest taboos in our society. Those affected often suffer in silence, and families touched by addiction rarely feel able to share their stories openly. Instead of being met with compassion, they are too often met with shame.

The truth is, addiction isn’t about alcohol, drugs, shopping, or even social media. It’s a coping mechanism, an attempt to soothe inner pain, disconnection, or distress. Until we start to recognize that, we’ll keep looking at the wrong end of the problem.

The reality is stark: addiction doesn’t discriminate. It affects the executive and the janitor, the teacher and the student, the parent and the child. Until we recognize addiction as a human health issue rather than a moral failing, we perpetuate cycles of silence that prevent healing and recovery.

Changing the way we talk about addiction is one of the first steps to changing how we respond to it.

And here’s where language matters. Words shape the way we think and the way we judge. Labels like “addict” reduce people to their struggle and reinforce stigma. By shifting towards more accurate and respectful terms, such as substance or behavioral use disorder instead of “addiction,” or “recurrence” instead of “relapse, we not only describe the reality better, but we also create space for dignity and recovery. Changing the way we talk about addiction is one of the first steps to changing how we respond to it.

The truth is, addiction isn’t about alcohol, drugs, shopping, or even social media. It’s a coping mechanism, an attempt to soothe inner pain, disconnection, or distress. Until we start to recognize that, we’ll keep looking at the wrong end of the problem.

Addiction is a Health Issue, Not a Moral Choice

Addiction is not a weakness, a lack of willpower, or a character defect. It is a health issue, a neurological condition that develops over time. Neurobiological research shows that addiction is an unhealthy coping strategy that gradually alters the brain’s reward system. This process often begins during adolescence, when the still-developing brain is especially sensitive to outside influences such as alcohol, drugs, or other high-reward behaviors. Over time, the brain starts to rely on these quick hits of relief rather than learning to regulate stress and emotions in healthier ways.

For understanding addiction as a medical condition, we must accept that it is not a sign of weakness or a lack of willpower. It is a chronic brain disorder recognized by DSM‑5 and ICD‑11, defined by:

- loss of control over use,

- continued use despite harmful consequences,

- tolerance and withdrawal,

- impairment in social and professional functioning.

Neurobiology: How the Brain Rewires Itself

Addiction represents one of the most complex challenges in modern medicine, involving intricate neurobiological processes that fundamentally alter brain structure and function. At the neurological core of addiction lies the brain’s reward circuit, which addictive substances hijack by activating the dopaminergic pathway connecting the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens. Research has consistently demonstrated that chronic substance use leads to persistent changes in brain reward systems, fundamentally altering the neural circuitry responsible for motivation and decision-making.

The concept of neuroplasticity plays a paradoxical role in addiction. While typically enabling learning and adaptation, repeated exposure to addictive substances exploits this mechanism harmfully. Over time, motivation circuits become increasingly sensitized while the prefrontal cortex’s ability to exert control becomes progressively weakened, creating a neurological environment where compulsion overtakes conscious choice.

Clinical examples

Modern clinical care begins with systematic assessment using DSM-5 and ICD-11 criteria. The DSM-5’s dimensional approach categorizes severity based on criteria met (mild: 2-3, moderate: 4-5, severe: 6 or more). Validated screening tools such as AUDIT, DAST-10, and ASSIST provide clinicians with reliable methods for early detection, which research has shown to be associated with improved treatment outcomes (Babor et al., 2001).

1. The Glass That Becomes a Habit

Marc, 45, a successful executive, begins with a glass of wine to relax after work. Over time, this ritual becomes a necessity. Without it, he feels tense and restless. Daily drinking eventually disrupts his sleep and family life. What started as a social habit evolves into alcohol dependence, driven by changes in the brain’s reward system.

2. Online Gambling That Consumes the Nights

Sofia, 22, a student, discovers online sports betting. At first, it feels like harmless fun, and early wins boost her confidence. Soon, she spends nights gambling, neglects her studies, and falls into debt. The thrill and illusion of control fuel her behavior. Her story shows how behavioral addictions can hijack the brain just like substances.

3. Painkillers That Become Indispensable

Claire, 35, receives opioid painkillers after surgery. Initially, they provide relief, but tolerance develops quickly. She increases doses and seeks multiple prescriptions. When she tries to stop, withdrawal symptoms and anxiety appear. What began as medical treatment turns into opioid dependence. Claire’s case highlights how addiction can emerge in medical contexts without any intention to misuse.

What These Stories Show

- Addiction has no boundaries: it affects executives, students, and patients alike.

- It often begins with ordinary behaviors (a drink, a game, a pill) that become survival strategies.

- Behind each case lies emotional or physical pain that the person is trying to soothe.

- Science explains the mechanisms, but society must provide compassion, support, and integrated solutions.

Building on this scientific foundation, the most crucial shift in understanding addiction is this: it’s rarely about the alcohol, the drug, or the behavior itself. Those are simply the visible outlets. What’s really happening is that the brain, wired for survival, finds a way to manage emotional pain it can’t otherwise regulate, stress, shame, loneliness, trauma, or that aching sense of emptiness that shadows so many of us.”

For one person, that might show up as a glass of wine that turns into a nightly necessity: for another, it’s gambling apps, compulsive overworking, or the quiet reliance on cocaine to fuel performance. And in younger generations, it often surfaces through shopping platforms or hours lost to online gaming or the endless scroll of social media.

The common thread isn’t the substance or the screen, it’s the brain’s need to fill emotional gaps, to quiet discomfort, and to cope with what feels unmanageable.

Understanding this changes everything. Addiction is both a disease that reshapes the brain and a coping mechanism for emotional pain. If we keep focusing only on the “thing”, the drink, the drug, the gambling app, or the email inbox, we’ll keep treating the symptoms while missing the causes. Real progress begins when we address the deeper conditions that drive people towards substances or behaviours in the first place.

Addiction in Today’s World

If addiction begins as a way of filling emotional gaps, then today’s culture has only multiplied the options for doing so. Each generation faces its own constellation of potential addictions, shaped by cultural pressures and whatever substances or behaviours are most accessible. Among younger people, the patterns increasingly point towards shopping, sugar, beauty culture, vaping, and the endless scroll of social media as ways to regulate difficult emotions. The rise of weight-loss drugs such as Ozempic reflects the resurgence of body-image pressures, fuelling disordered eating and unhealthy ideals that echo the “heroin chic” era of the 1990s.

In the professional world, the picture looks different but no less concerning. Research from France highlights how “stress at work, changing schedules, [and] repetitive tasks” are strongly linked to alcohol and tobacco consumption. It paints a picture many will recognize: workplaces that look busy and connected on the outside, but which, on the inside, foster hidden isolation, competition, and a lack of genuine support. In these environments, alcohol after hours, smoking breaks, or quiet reliance on stimulants often become socially accepted ways of coping, even framed as team bonding or informal networking.

Today, quick fixes have never been closer to hand. From gambling apps to prescription drugs to surgical shortcuts, our culture offers quick fixes but little room for the emotional vulnerability that drives them.

The Real Cost of Quick Fixes

The trouble with quick fixes is that they rarely fix anything for long — and sometimes, they make things much worse. Research shows, for example, that gastric band surgery can carry serious risks: suicide rates post-procedure are 2.7 per 1000 patients, and self-harm is nearly twice as likely compared to non-surgical groups. In real terms, that means hundreds of people each year end up in crisis, not because of the surgery itself, but because the underlying mental health challenges that drove their eating in the first place were never addressed.

When food becomes someone’s way of coping with loneliness, boredom, or sadness, taking it away without providing healthier tools can leave them more vulnerable than before. Studies confirm this: people who undergo bariatric surgery without adequate psychological support face a significantly higher risk of crisis. It’s the equivalent of removing a life raft without teaching someone how to swim. And it’s not just food; the same principle applies across alcohol, gambling, overwork, or any other behavior that hides emotional pain.

Weight-loss drugs like Ozempic raise similar concerns. While there are clear medical benefits in some cases, research and clinical experience suggest they can also become another shortcut, one that bypasses the deeper emotional and psychological work needed for lasting wellbeing. Put simply, no pill or procedure can substitute for addressing the whole person. Lasting recovery depends on treating both the behavior and the underlying challenges, whether the struggle is with food, alcohol, or anything else.

Why Silence Makes It Worse

We don’t whisper about cancer. We don’t shame people for grieving. We rally, we cook meals, we send cards, we offer compassion. Yet when it comes to addiction, the tone shifts. Instead of empathy, people are too often met with judgment, shame, and moral condemnation. This double standard is not only unfair but also dangerous. Shame drives addictive behaviors underground, making recovery harder and recurrence more likely.

The workplace adds another layer to this silence. Research from France shows how degraded working conditions, long hours, shifting schedules, repetitive tasks, fuel increased alcohol and tobacco use as workers look for “escapes from work constraints.” In plain terms, people turn to substances to manage pressures their workplace won’t acknowledge. And when organizations ignore systemic issues like toxic management, impossible deadlines, or a lack of psychological safety, they inadvertently reinforce the very struggles their employee assistance programs are meant to solve.

If silence fuels the problem, then conversation must become part of the cure.

Moving Towards Solutions

Real change starts when we bring substance and behavioral use disorders out of the shadows and talk about them as openly as we now talk about depression or anxiety. Conditions once weighed down by stigma are now met with greater compassion, information, and support. Addiction deserves the same treatment.

That shift requires a few concrete steps:

- Open conversations: replace hushed judgments with honest dialogue in families, schools, and workplaces. Speaking with the same matter-of-fact tone we use for depression creates space for people to seek help openly without shame

- Accessible, diverse support: therapy, recovery coaching, community groups, and alternative approaches should be readily available. Effective care always addresses the physical, psychological, and social dimensions together.

- Treat the whole person: moving beyond symptom control to address underlying needs. Integrated approaches, not isolated interventions, give people the best chance of sustainable recovery.

- Employer responsibility: go further than surface-level wellness programmes. Inclusive cultures, genuine mental health support, and awareness of how management practices create stress or isolation all make a difference.

Research consistently shows that people need genuine relationships, purpose, and belonging, not another quick fix. At its core, the shift is simple but profound: addiction flourishes in isolation, and the antidote is connection.

A Collective Responsibility

Substance and behavioral use disorders reach across every community, every workplace, every family. Yet so does the possibility of recovery. The moment we replace silence with conversation, stigma with understanding, judgment with compassion, we begin to change the landscape.

The moment we replace silence with conversation, stigma with understanding, judgment with compassion, we begin to change the landscape.

This is not about excusing harmful behaviors or denying responsibility. It’s about recognizing that no medical condition has ever been improved by shame. Recovery requires courage, support, and often professional guidance, but it begins with connection. And connection is something each of us can offer.

Together, we can create environments where recovery is not hidden but openly supported. Where schools educate without fear, where workplaces foster safety, and where communities open their doors instead of closing their eyes.

In a culture built on quick fixes and constant disconnection, choosing to honor real human needs, belonging, purpose, and relationships is an act of radical hope. And hope is contagious.

It’s time to talk, time to listen, and time to build communities where recovery can thrive.

Elizabeth Walker

Elizabeth Walker