By Dr. Oliver Rossmannek

The users of peer-to-peer platforms come and go, but they do so in very different ways. I outline four unique paths for platform users and show their distinct motivations. Platform managers need to know these paths in order to understand their users and to design successful strategies.

Peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms have become key players in many sectors. Home-sharing platforms, such as Airbnb, Vrbo, Novasol, and Canopy & Stars, enable millions to go on holiday every year. Retail platforms, such as eBay, Etsy, Vinted, and Mercado Libre, have replaced flea markets for many consumers. Entrepreneurs and their supporters come together on platforms such as Kickstarter, Indiegogo, Patreon, and Startnext. Ride-sharing platforms, such as Uber, Lyft, Bolt, and DiDi, have become important elements of many metropolitan transport systems. The idea behind all of these business models is that users can be service providers (e.g., drivers, hosts, entrepreneurs, and sellers), customers, or even both.

Table I: P2P-platform sectors with examples

| P2P sector | Example platform companies |

| Home-sharing | Airbnb (USA), Vrbo (USA), Homestay (Ireland), Novasol (Denmark), Wimdu (Germany), FlipKey (USA), misterb&b (USA), Canopy & Stars (UK) |

| Retail | eBay (USA), Vinted (Lithuania), Kijiji (Norway), MercadoLibre (Argentina), Etsy (USA) |

| Finance | Kiva (USA), Lendwithcare (UK), Kickstarter (USA), Zidisha (USA), Indiegogo (USA), Patreon (USA), Startnext (Germany), Leetchi (France) |

| Ride-sharing | Uber (USA), Lyft (USA), Bolt (Estonia), Grab (Singapore), DiDi (China) |

| Services | TaskRabbit (USA), Thumbtack (USA), Pickle (UK) |

| Work or storage space-sharing | desksnear.me (USA), Coworker (UK), Storemates (UK) |

| Food-sharing | foodsharing.de (Germany), Karmalicious AB (Sweden), Olio (UK) |

| P2P car-sharing | Turo (USA), Getaround (USA), SnappCar (Netherlands) |

| Camping vehicle-sharing | Yescapa (France), PaulCamper (Germany), RVshare (USA) |

It was once thought that monopolies would arise in many platform-dominated sectors[1]. This “winner-takes-it-all” dynamic should have resulted from network effects. The larger the network of users, the more attractive the platform becomes for new users, which, in turn, results in further user-base growth and, ultimately, in the emergence of a monopoly.

The implication that many platforms drew from this prediction was that they had to grow their user bases at all costs. The easiest way to do so was through massive investment. Backed by venture-capital firms, the platforms spent billions on subsidizing users and on wide-ranging advertising campaigns. For instance, in 2019, SoftBank alone invested nearly $20 billion into several ride-sharing platforms[2]. The resulting cash flow was used to reduce drivers’ fees and to make rides cheaper for customers[3]. Unfortunately for customers, those days seem to be over. The venture-capital firms soon discovered that the winner-takes-it-all dynamic is a fairytale in many sectors.

Throwing money at platform users may help to attract and keep them for a while. However, it has been proven to be unsustainable as a strategy. As soon as the money dries up, the competitive position of the platform is likely to be in danger. The fortunes of a platform can turn fast because of the high turnover of users. For instance, for Uber it was found that only 25% of new drivers were still driving for the platform a year later[4]. Consequently, platforms learned something that traditional service firms had long known: attracting and keeping users requires sophisticated service strategies. Different platform users can have very different needs and motivations.

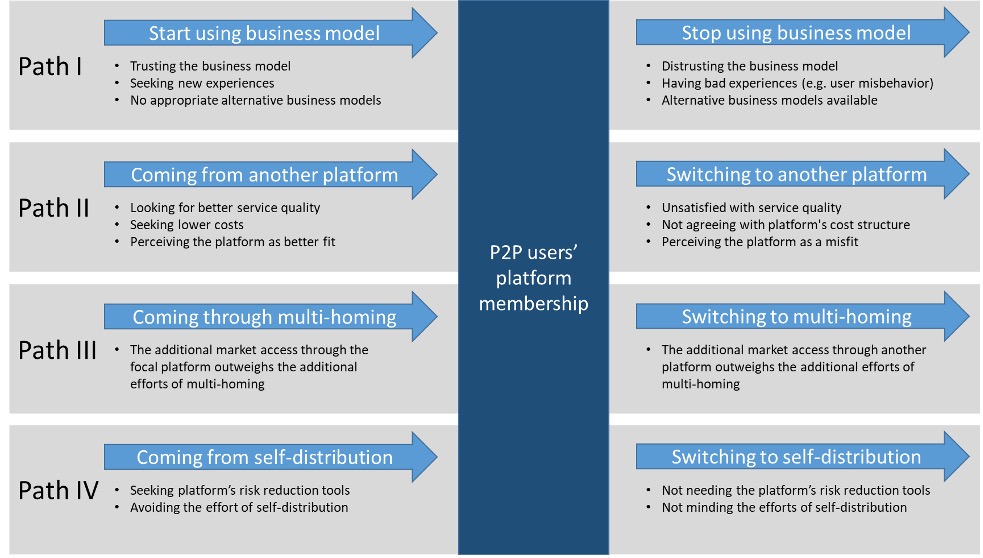

Drawing on many years of studying platforms and on the extensive literature on the subject, I argue that most platform users come and go on four distinct paths. Each path is associated with distinct motivations. For instance, some Uber users may be switching from Lyft, while others are trying ride-sharing for the first time; some Airbnb hosts may be driven chiefly by economic motives, while others are participating in order to form new social connections. Due to this variety, platform managers need to familiarize themselves with the four paths in order to devise successful strategies.

The four paths

Figure 1: The four paths of platform users

Path I: Start/stop using the business model

Platforms that pioneer a business model face the problem of ensuring that users accept it. Not everyone is keen on the idea of renting an apartment from or to someone that they just found on Airbnb. Likewise, many people do not like the idea of stepping into strangers’ cars instead of hailing a yellow cab. Even if users do embrace the business model initially, they may withdraw their support later. In general, the questions that follow are key to (potential) users.

“Do I trust the business model?” Trust has been identified as key barrier to the use of P2P business models[5]. Users may perceive a business model, such as ride-sharing or home-sharing, as trustworthy, or they may not. Often, trust simply accumulates over the years as a business model garners wider acceptance in society. Potential users observe early adopters until they eventually decide that the business model is safe enough for them to give it a go. Even if the business model seems too risky to users initially, the platform can try to build trust. A strong brand, a decent review system, insurance schemes, money-back guarantees, a 24/7 emergency call center, and verification mechanisms for service providers (e.g., for Uber drivers’ licenses) may allow users to trust the platform. When this is done right, platforms can even become more trustworthy than traditional (non-platform) service providers. For example. a recent poll found that Gen Z perceives Airbnb as substantially more trustworthy than the largest U.S. airlines and hotel companies[6].

“Does the business model promise good experiences?” Several studies have shown that expectations about experiences can influence users positively as well as negatively[7]. The positive influence of experience on the usage of a P2P business model is driven by users’ preference for uniqueness on P2P platforms and the expectation of meeting interesting people from all over the world[8]. The negative influence comes from experiences with unpleasant users or from witnessing the unpleasant experiences of other users[9]. In general, platform managers should not underestimate the role of experiences and feelings. The authors of this text once tried to buy a pair of really cheap sneakers on eBay. They wound up being scammed. As a consequence, the author would only patronize brick-and-mortar footwear stores for several years as a result. An experience does not need to be first hand to affect users – interested readers may want to visit the website airbnbhell.com and read about home-sharing nightmares. Experiences also work the other way around. If one simply wants to support someone on Kickstarter and this act of support produces a lifelong friendship, one may remain a crowdfunding enthusiast for life. Overall, platforms need to minimize bad experiences and foster good ones. The approaches that recommend themselves most readily are banning troublesome users with low ratings and adjusting matching algorithms to reconnect users who have rated each other highly in the past. More pro-active approaches are often difficult to identify. For example, Uber once planned to use AI in order to detect drunk users and deny them access to rides[10]. Such an innovative approach could help to avoid violent interactions between drivers and drunk passengers, but it also leaves drunk passengers alone and in danger in the streets.

“Are there alternative business models that fulfill my needs?” In many sectors, it has been shown that P2P models function as alternatives or substitutes to traditional services. Ride-sharing and taxis supply a salient example, as well as home-sharing and hotels, and second-hand retail platforms and thrift shops. In some cases, the availability of alternatives means that the user does not even begin to use a P2P business model. A person who is living right next to a thrift shop will most likely seek their next party outfit there instead of on an online platform for second-hand clothing. Platform managers need to be aware that they compete not only against other platforms but also against potential alternatives from non-platform sectors. Picking up this fight can make sense if one’s business model is competitive. For example, a strong company may offer ride-sharing trips that are cheaper than taking a taxi. At other times, it makes sense for platforms to focus on niches that are not covered by their non-platform competitors. For instance, crowdfunding has become a standard way for publishing niche content that is not suitable for mass-market publishers[11], such as fantasy board games.

Path II: Switching platforms

Once users have accepted a business model, competition between platforms becomes more important. Whether someone rents a holiday home via Airbnb, Vrbo, Booking.com, Homestay, Novasol, FlipKey, misterb&b, or Canopy & Stars depends on several factors. Existing research has shown that three questions are essential for existing platform users.

“Am I satisfied with the service?” It has been shown that service quality matters a lot for the users of P2P platforms[12]. Platforms are in the service business. In almost all cases, they provide a matching service. This service can be very basic (e.g., the provision of a list of unicorn lunch boxes for under $30 on Etsy) or quite advanced (e.g., matching ride-hailing drivers and their customers in downtown Manhattan). Most platforms also offer additional services, such as payment processing, displaying additional product information, or even loans. If users perceive service quality as inappropriate, they are likely to switch to a competitor. However, the appropriateness of service quality depends on the user segment. For instance, many home-sharing hosts are simply looking for a matching service and often end up with the market leader (e.g., Airbnb or Vrbo). Others are much more interested in administrative support. Platforms such as DanCenter or Novasol target such hosts and assume responsibility for activities such as cleaning and the delivery of keys to guests.

“Can I live with the costs?” Studies demonstrated that users’ choice of platform and their loyalty to it depend on the perceived costs or price of the platform and its services[13]. Platforms typically carry several costs for users. The most visible ones are the fees that the platform charges directly. For instance, Kickstarter takes 5% from the total sum that is raised for a successful project, as well as 3% from each individual payment[14]. Airbnb usually charges fees of 3% for hosts and of 14% for guests[15]. The non-monetary costs include the collection of user data and targeted advertisement. The users of a platform that is not the market leader also “pay” by agreeing to target a smaller user base. For example, a Lyft driver in a city with more Uber customers “pays” by accessing fewer customers via the platform. Platforms do not need to be the cheapest to succeed. Instead, good communication is key. Providing high-quality services (e.g., a 24-hour hotline or even face-to-face support) typically enables a platform to charge higher fees. The challenge is to communicate those advantages successfully—users must know what they are paying for.

“Is the platform a good fit for me?” Finally, fit can make a difference for some users. The research on user-platform fit is scarce, but it has been shown that compatibility (i.e., users’ social values and usage patterns) is important for the users of platform services[16]. Many people do not really care if they book via Airbnb or some other platform. However, some people might find it more comfortable to use a niche platform. For example, the platform misterb&b focuses on travelers from the LGBTQ+ community and makes it easier for them to find tolerant hosts. If they follow Michael E. Porter’s advice, platforms should avoid becoming “stuck in the middle”[17]. Thus, it is advisable for platforms to either target the mass market or to focus on a specific user group that has specific needs.

Path III: Multi-homing

Platform managers often try to lure users to only use their own platform ecosystem, a phenomenon that is called single-homing. In reality, however, multi-homing is often the norm. For instance, many drivers work for Uber and Lyft at the same time. On the customer side, many shopaholics do not abandon their search if they fail to find an appropriate second-hand Louis Vuitton piece on eBay; they simply move onto Vinted. Whether multi-homing is an option for users or not depends mainly on the answer to a single question.

“Do the benefits of a larger market outweigh the additional effort that multi-homing requires?” The decision to engage in multi-homing usually results from cost-benefit reasoning[18]. Multi-homing enables users – both service providers and customers – to access the markets of several platforms. In some cases, this results in substantial benefits. Hosts may offer their holiday home on several platforms in order to be more visible to guests and, ultimately, to increase their booking rate. If this is true of many hosts, the offerings of platforms become more similar. This similarity, in turn, dramatically reduces the benefit that guests derive from searching for offers on several platforms. The costs of multi-homing mostly originate from the increase in administrative effort that it entails. Users need to maintain profiles on several platforms, to update their data, and to familiarize themselves with different platform ecosystems. Sometimes, this is easy; at other times, it is not. For example, a home-sharing host can use rental-management software, such as Hostaway, Smoobu, or Uplisting, which makes it easier to keep the availability of a holiday home up to date on all home-sharing platforms. Conversely, it is difficult to launch a crowdfunding campaign on Kickstarter and Indiegogo simultaneously because the two have very different structures and because keeping track of comments and regulations is demanding[19].

What can platform managers learn from the foregoing? One option would be to decrease the incentives that their users have to use other platforms. Some platforms require single-homing in their terms of use; however, this requirement cannot always be enforced effectively. Other platforms increase the costs of multi-homing by introducing unique rules and software elements that are different from those of their competitors. However, in some cases it even makes sense to encourage multi-homing. The easier it is for users from other platforms to switch to one’s platform, the greater the potential of that platform to generate additional revenue.

Path IV: Self-distribution (intermediation and disintermediation)

Not every user needs a platform to interact with their peers. Instead of selling one’s old stuff on eBay, a customer may switch to self-distribution and organize a car-boot sale in their backyard. Just as in the other paths, this proposition cuts both ways: platforms can become intermediators and gain users or, in the case of disintermediation, lose them. Disintermediation typically occurs only in select cases. For instance, if a customer would like to re-book their holiday home from last summer, they may speak to the host directly in order to circumvent the platform and its fees. When the same users are about to travel to a new destination, they are still likely to use Airbnb or Vrbo. When and how (dis)intermediation will occur is relatively difficult to predict. Out of all the paths, (dis-)intermediation on P2P platforms has received the least attention by researchers. However, especially two questions seem to matter.

“Can I live without the risk-reducing tools of the platform?” Many scholars see risk mitigation as a primary reason for the existence of platforms[20]. Hence, platforms have implemented all kinds of risk-reducing services, such as insurances, certifications, and review systems. While these services are a key source of value for many users, some do not need them. After contact has been established, repeated transactions (e.g., re-bookings of holiday homes) can be based on the trust that has been established in the past, which substitutes the risk-reducing tools of the platform. Occasionally, the value of the transaction is simply too small. Most of those who are looking to buy a used radio for $5 from a flea market can probably live with the risk of finding out that it does not work once they try it out at home. In other cases, users may already have a solid reputation. For example, the fantasy-book author Brandon Sanderson is a well-known figure in his community and has many loyal fans. His recent Kickstarter campaign closed at over $41 million, which was put up by more than 180,000 backers[21]. It is likely that Sanderson’s fans did not care much about Kickstarter’s risk-reducing tools.

“How much effort does it take to do it alone?” Support with the administrative aspects of the transaction can be an important aspect of value creation on platforms[22]. A well-designed IT infrastructure helps users with the boring and nasty aspects of transactions: invoicing, the formulation of terms and conditions, and the generation of automated translations. High-frequency transactions are likely to benefit particularly from support of this kind. For example, an Uber driver could not fill out 50 invoices by hand within a day. In contrast, a week-long stay at a holiday home only requires one invoice to be issued. Another criterion is the availability of outside options for administrative support. Invoicing is not rocket since; there is a Word template for it. More professional users can also use specialized software solutions, such as Shopify, which help them to navigate the e-commerce jungle.

In general, the question of disintermediation is a question of value creation. If the platform is only perceived as an intermediary that takes a cut, users will try to avoid it. However, if the platform offers valuable services, users will stick with it even when they can circumvent it. The home-sharing platform Novasol is a salient example. It offers numerous services to hosts, including communicating with guests, managing reservations, and estimating an optimized rental price.

Conclusion

Usually, not all paths are equally relevant at the same time. When the business model is new, users mostly come and go via Path I (starting or ceasing to use a business model). In many countries, business models such as ride-sharing and home-sharing are very well established, which often reduces the importance of this path. However, even some major e-commerce markets differ in this regard. For instance, the era of home-sharing is yet to dawn in China, and ride-sharing exists only in a few German cities due to regulatory issues from the past. In these markets, Path I matters a lot.

Sometimes, it is not geographical restrictions but the specificities of a given sector that constrain paths. For example, in Path IV (self-distribution), it may be viable for the buyers and sellers of used items to circumvent platforms such as eBay or Vinted by simply communicating via email because cheap items, such as used t-shirts, rarely need to be insured by the platform. For home-sharing hosts and their guests, however, risk-reduction tools are often essential. In this sector, self-distribution mostly occurs in the context of re-bookings. Since re-bookings are rare on most home-sharing platforms, this threat is often relatively small. Consequently, the most important lesson for platform managers is to conduct thorough market research. In my experience, many platforms know surprisingly little about the characteristics, motivations, and needs of their users. In one case, I observed that the platform did not even know the age of its users. Where users come from and where they go is a much more complicated question and hence often a mystery for platform managers.

Market research can be based on internal data, the distribution of surveys, or interviews with users. Internal data can show how many newly created accounts remain active and for how long, which can help the platform to evaluate its return on user-acquisition costs. Surveys may highlight the weaknesses of a platform, such as poor service quality or ineffective measures to reduce user misbehavior[23]. These approaches, however, only scratch the surface. They show where users come from, if they show anything at all, but they almost never reveal where those users go or why.

Platform managers who really want to understand their users need to communicate with them intensively. They can do so through focus interviews or, alternatively, by simply assuming the identity of a user. Dara Khosrowshahi, the Uber’s CEO, recently spent several months as an undercover driver[24]. Airbnb’s CEO Brian Chesky not only sleeps in Airbnb apartments but also rents out a room from his own house on the platform[25].

Focusing on market research can produce a comprehensive mapping of the strengths and weaknesses of a platform. Whether a certain development reflects an actual weakness depends on whether it is caused by incoming or outgoing users. For instance, a high multi-homing rate can be caused by outgoing users who consider the market of the platform to be too small. It can also be caused by incoming users, which would indicate that the platform is easy to access for those who rely on rival platforms. In that case, the receiving platforms can build on its advantage by attracting even more users.

In conclusion, I encourage platform managers to analyze user behavior in much greater depth. Only those who really understand their users can design successful strategies in highly competitive platform markets.

Dr. Oliver Rossmannek

Dr. Oliver Rossmannek