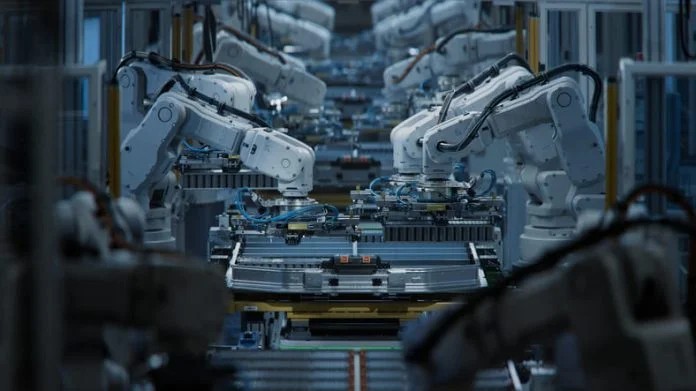

Over the past decade, digital transformation has become the dominant narrative in advanced manufacturing. Companies have invested heavily in data platforms, artificial intelligence, digital twins, and predictive analytics, all with the promise of creating smarter, more agile operations. Yet as these initiatives mature, a growing number of manufacturing leaders are encountering an unexpected ceiling: the physical systems beneath their digital layers are struggling to keep up.

Smart manufacturing strategies often assume that once data flows are optimized and algorithms refined, performance improvements will naturally follow. In practice, digital intelligence remains tightly coupled to the reliability of physical components. When materials deform, drift, or degrade under real operating conditions, even the most sophisticated digital systems are forced to compensate. In many facilities, elements such as quartz glass tubes used as physically constrained interfaces in smart manufacturing systems quietly determine whether digital insights translate into consistent operational outcomes.

As a result, the limits of smart manufacturing are increasingly defined not by software capability, but by material behavior at the operational edge.

The Digital–Physical Gap in Smart Manufacturing

Digital transformation initiatives tend to prioritize visibility and control. Sensors generate data, platforms aggregate insights, and algorithms propose optimized actions. This approach has delivered undeniable gains in efficiency and responsiveness. However, it often underestimates the complexity of the physical environments in which these systems operate.

Manufacturing systems are exposed to heat, vibration, chemical interaction, and continuous mechanical stress. Over time, these factors alter material properties in ways that digital models rarely anticipate. When physical components behave inconsistently, digital representations lose fidelity. The result is a widening gap between what systems predict and what actually occurs on the factory floor.

This gap is rarely visible in pilot projects or short-term deployments. It emerges gradually, as systems scale and operate continuously.

Why Physical Constraints Are Strategic, Not Technical

Physical constraints are often framed as engineering challenges to be solved at the operational level. In reality, they represent strategic limitations that shape what smart manufacturing can achieve. When materials introduce variability, organizations are forced to invest additional resources in calibration, maintenance, and exception handling.

From a strategic perspective, this erodes the return on digital investments. Data-driven decision-making becomes less reliable, predictive maintenance models generate noise, and automation systems require more human oversight. The promise of autonomy is delayed not by insufficient data, but by insufficient physical stability.

Leaders who treat material performance as a secondary concern risk building digital strategies on fragile foundations.

Scaling Smart Manufacturing Exposes Material Limits

Many smart manufacturing initiatives perform well at limited scale. Early successes reinforce confidence in digital tools and encourage broader deployment. However, scaling introduces new stresses. Systems operate longer hours, process variability increases, and environmental conditions fluctuate.

At scale, small material inconsistencies become systemic issues. Components that expand unevenly, degrade chemically, or lose surface integrity can affect alignment, heat transfer, and signal accuracy across entire production lines. Digital systems attempt to compensate, but compensation adds complexity and reduces transparency.

The more sophisticated the digital layer becomes, the more it depends on predictable physical behavior underneath.

Execution Bottlenecks in High-Temperature Operations

High-temperature processes highlight this dynamic particularly clearly. Heating, thermal cycling, and aggressive operating conditions accelerate material fatigue. Components exposed to these environments must maintain dimensional and chemical stability to preserve process consistency.

When materials cannot meet these demands, organizations often experience execution bottlenecks. Throughput targets are missed, quality variability increases, and maintenance schedules become reactive. Digital systems may identify the symptoms, but they cannot eliminate the root cause.

In such contexts, supporting elements like quartz glass crucible applications supporting repeatable high-temperature industrial processes are selected not for visibility, but for their ability to preserve consistency under sustained thermal stress. Their contribution is indirect yet decisive: they enable processes to remain predictable enough for digital optimization to function.

Rethinking the Role of Materials in Digital Strategy

As smart manufacturing evolves, materials can no longer be treated as interchangeable commodities. They are integral to system behavior and should be evaluated alongside software and automation platforms. This requires closer collaboration between strategy teams, digital leaders, and engineering functions.

Organizations that align material selection with digital objectives reduce friction between physical reality and digital intent. They create systems where data reflects true process behavior, rather than compensating for material-induced noise.

This alignment also simplifies governance. When physical systems behave consistently, fewer corrective rules and overrides are required at the digital layer.

From Digital Ambition to Physical Readiness

The most successful smart manufacturing strategies increasingly recognize physical readiness as a prerequisite for digital ambition. Rather than asking how quickly new technologies can be deployed, leaders are beginning to ask whether their physical systems can sustain the level of precision and stability those technologies demand.

This shift reframes digital transformation as a holistic effort. Software, data, automation, and materials are evaluated together as parts of a single system. Constraints are addressed upstream, before they undermine downstream analytics and decision-making.

Conclusion

Smart manufacturing has delivered powerful tools for visibility and optimization, but its future progress depends on confronting an uncomfortable truth: digital systems are only as reliable as the physical environments they operate within.

Physical constraints are not peripheral technical issues. They are strategic factors that define the limits of digital transformation. Organizations that acknowledge and address these constraints position themselves to extract lasting value from smart manufacturing, while those that ignore them risk building increasingly complex digital layers atop unstable physical foundations.

In the next phase of industrial transformation, competitive advantage will belong to manufacturers who understand that intelligence must be supported not only by data and algorithms, but by materials capable of sustaining reality itself.