By Adam J. Bock and Denis Frydrych

Crowdfunding is a much-hyped tool for entrepreneurs to access capital anywhere in the world. While media and public perception have generally been positive, the data suggests high failure rates for crowdfunding campaigns. We analysed more than 80,000 Kickstarter projects and found surprising success factors for raising capital. We observed one artist-entrepreneur’s campaign to reveal the secrets behind the statistics. Online crowdfunding is fundamentally different from traditional entrepreneurial finance, but there are ways to make it work.

“Most of the things that succeed in life are just because you are too stupid to realize that you have already lost the game and you show up anyways.” (Cory Cullinan, aka “Doctor Noize”)

In 2014, more than 1,200 online crowdfunding platforms facilitated approximately $16bn of investment across the globe. Current estimates suggest investment volume exceeded $30bn in 2015.1 Online sites such as Kickstarter, Indiegogo and CrowdCube are potentially disruptive platforms that democratise access to start-up investments. Crowdfunding raises capital from the “crowd”, an ever-changing online audience of everyday people. Entrepreneurs promise financial returns or non-financial ‘rewards’ for investing in social, artistic, technological, and commercial projects.2 The online platforms help entrepreneurs fund projects and ventures when friends, family, and private investments are not viable or sufficient. Some estimates suggest that annual crowdfunding volume will eclipse total venture capital investment within the next few years.3

Crowdfunding is making “Noize”

The rapid growth of crowdfunding has caught the attention of regulatory authorities and policymakers. The European Commission is actively studying the value and risk of crowdfunding in 21st century entrepreneurial ecosystems.4 Some EU economies have opened regulatory frameworks to facilitate crowdfunding, despite significant concerns about accountability and the lack of protection for investors from fraud, deceit, or incompetence. Given the fluid, evolving nature of the crowdfunding industry, it is important to understand how and why some entrepreneurs are impressively successful in raising capital from the crowd while others fail dramatically.

Certain projects are crowdfunding in name only. Video game sequels provide the most obvious example. These campaigns often rely on a massive, enthusiastic fan base to pre-pay for a copy of the game on release. In other words, these are product launches based on prior commercial success that only use crowdfunding to shift implementation risk to the customers. While this risk-shifting phenomena warrants investigation, these projects do not leverage or solicit the wisdom of the crowd. We focus, therefore, on novel, one-off projects as the intended beneficiaries of fully disintermediated crowdfunding efforts.

We studied data from more than 80,000 crowdfunding campaigns around the world to explore the characteristics and processes that drive success. But these numbers do not tell the full story. To reveal the secret life of crowdfunding, we also report on a three year, in-depth study of one entrepreneur’s journey to create and produce an opera for children. Cory Cullinan, aka “Doctor Noize”, used Kickstarter to raise $50,000 for “Phineas McBoof Crashes the Symphony”. This “edutainment” opera was recorded with the City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Kyle Pickett, and international opera stars Isabel Leonard and Nathan Gunn.5

(from right to left) Conductor Kyle Pickett, baritone Nathan Gunn, soprano Isabel Leonard, composer Cory Cullinan (aka “Doctor Noize”).

In contrast with traditional entrepreneurial financing like bank loans and venture capital, crowdfunding is not about who you know, where you have been, your sales pitch or even returns potential. Successful campaigns leverage the online platform to inspire a project-specific syndicate. Effective campaigns are co-created by the entrepreneur and a previously hidden set of vocal, involved supporters. Crowdfunding works when the project and syndicate identities align; when the backers say (to quote Doctor Noize): “We’re with the band”.

The hard numbers of crowdfunding

No matter what the landing page of crowdfunding platforms suggest, crowdfunding success is neither easy nor guaranteed. Early in the process, Cullinan saw the reality behind the crowdfunding PR:

“I am doing the Kickstarter campaign to raise the required money for this project to responsibly move forward. However, I do think that people less frequently look at Kickstarter as an investment opportunity. People look at Kickstarter as something that is fun and emotional so that they want to be involved in it. As beautiful conceptually crowdfunding is, at the end the funding matters.” (Cullinan)

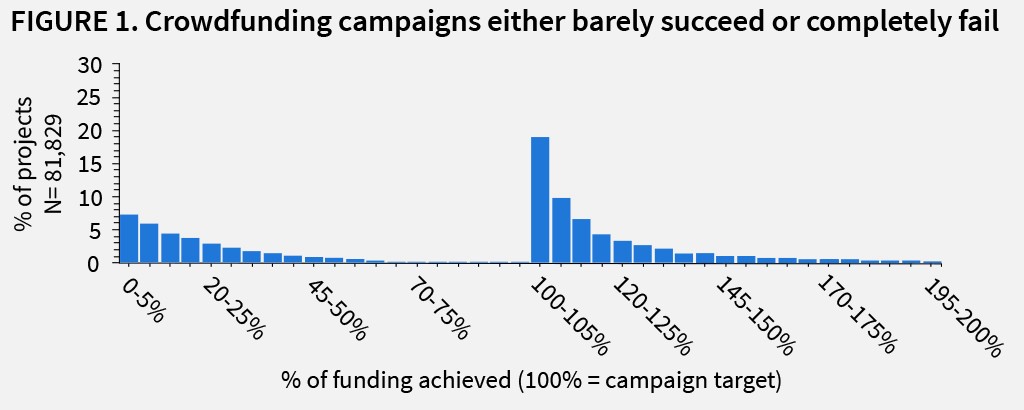

When crowdfunding was new, campaign success rates were high. Now, the novelty has worn off and backers are savvy about vetting projects. Campaign success rates across leading reward-crowdfunding platforms have fallen to about 33%. The distribution of funding outcomes, however, tells a much more complex story. Campaign funding outcomes (shown in Figure 1 below) are bimodal, revealing underlying dynamics that rapidly encourage or restrict capital allocation to specific projects.6 The vast majority of reward-crowdfunding projects either succeed by a small margin or fail by a large margin.

Early research seemed to show that crowdfunding was very similar to private fundraising. Network size and pitch quality were key drivers of success. But as crowdfunding has evolved, these are no longer clear ‘signals’ of quality or legitimacy.7

Like many entrepreneurs, Cullinan saw crowdfunding as a means to an end. Driven by a vision of making musical education approachable and entertaining, he had produced three albums, two books, and a mobile app. His inspiration for a 21st century successor to Prokofiev’s iconic “Peter and the Wolf” required resources of a different sort. His vision attracted world-class talent. Grammy Award-winning soprano Isabel Leonard, baritone Nathan Gunn (one of People Magazine’s “sexiest men” in 2008), and renowned symphony conductor Kyle Pickett all agreed to donate their time. But Cullinan still needed to pay for an orchestra, travel and accommodations, and extensive recording and mixing assets. Online crowdfunding seemed like a good match for his mission-driven, socially valuable creative project. Rewards for donations also seemed obvious, ranging from downloads of the album to participation in the recording event.

“The objective of this project is to produce and record a musical theatre that teaches children about classical music. Too often classical music is performed for and attended by adults. This project creates orchestral music written directly for children so that it appeals to them and in turn attracts them to orchestral music to master the ideas and concepts of classical music. My dream [is]… there will be thousands and thousands of children who are listening to classical music.” (Cullinan)

After six months of intense preparation, the crowdfunding campaign for “Phineas McBoof Crashes the Symphony” launched on Kickstarter in October 2013. The campaign site provided extensive details about the project, positive critical reviews from the prior albums, and a professionally-produced video including Leonard, Gunn, Pickett, and even Cullinan’s daughters. On the first day, the campaign raised 10% of the funding goal.

“The first days of the campaign had been a success. With the initial funding coming in, people believed that something exciting was happening. People wanted to get on board, and the campaign, its content and the early money raised communicated a positive vibe.” (Cullinan)

The campaign was listed in Kickstarter’s “What’s Popular” lead page, driving more traffic to the campaign site. The forecast looked good. The forecast was wrong.

A Level Playing Field?

Crowdfunding appears to offer a ‘level playing field’ for entrepreneurs and prospective investors. The platform provides a standardised template for communicating project information that is transparent and equally available to everyone. Anyone with a registered account can communicate with the entrepreneur, asking questions or providing feedback. All participants know the rules, costs, risks, and rewards.

The truth is less sanguine. Platforms make no guarantees about the representations of the entrepreneurs, relying instead on the wisdom of the crowd, the resources and insights of the users, to identify problems or misrepresentations.8 As with traditional finance, information asymmetry influences how entrepreneurs and investors interact. The platforms promote projects based on unwritten or arbitrary heuristics. The standardised platform and network effects may encourage herding behaviour; most projects capture the majority of their funding in the opening days of the campaign.9

Campaign entrepreneurs have skewed incentives for disclosing evolving information about the project. Similarly, entrepreneurs have little or no control over who actually views the project site, beyond direct contact with their extant network prior to and during the campaign. It should not be surprising that crowdfunding campaign pitches often look like traditional business plan pitches, with nods to specific socially redeeming outcomes. Entrepreneurs, like Cullinan, often invest heavily in time and money to develop the pitch – it is, after all, the first impression potential backers will receive.

“In order for anybody to be interested in the Kickstarter campaign, I had to create good campaign content. Things like a campaign video with the team and social media engagements absorbed a lot of time and budget to get the word out. I would not do these things if they weren’t needed for the Kickstarter campaign.” (Cullinan)

Crowdfunding is not, however, traditional fundraising. Backers want to be part of something bigger than just their investment – the whole needs to be greater than the sum of the parts. Projects over-reliant on the entrepreneur’s initial network and a glossy video pitch tend to fall short. After all, if entrepreneurs could access funds by telling a good story to their current network, why bother with the time, effort and transaction fees required by the online platform?

real time.

Statistical analysis of more than 80,000 Kickstarter projects told us what entrepreneurs do in successful campaigns. But it could not tell us why those choices attracted backers. For that, we needed to see the full cycle of a campaign, from project idea inception through the campaign and ultimately project implementation. That brings us back to Doctor Noize. We had been studying Cullinan’s entrepreneurial activities for three years before his crowdfunding effort, and we followed his campaign through the subsequent recording of the opera. We discovered that the secret life of crowdfunding is both simpler and stranger than the databases reveal. Ultimately, successful reward-based crowdfunding of novel creative projects requires authenticity, inspiring a syndicate, and constantly re-creating the campaign in real time.

The secret life of crowdfunding

Success in traditional entrepreneurial finance is often attributed to the quality of the opportunity and the credentials of the entrepreneur. Private investors rely on key gatekeepers and referrals to filter out the vast majority of deals from reaching their desks. Crowdfunding novel, creative projects is clearly different. The transparent nature of the online platform gives investor-donors access to hundreds, if not thousands of alternate projects that claim to make a difference. Donors are not necessarily swayed by prior success or expected project impact. Early enthusiasm can fade quickly; first impressions may not last.

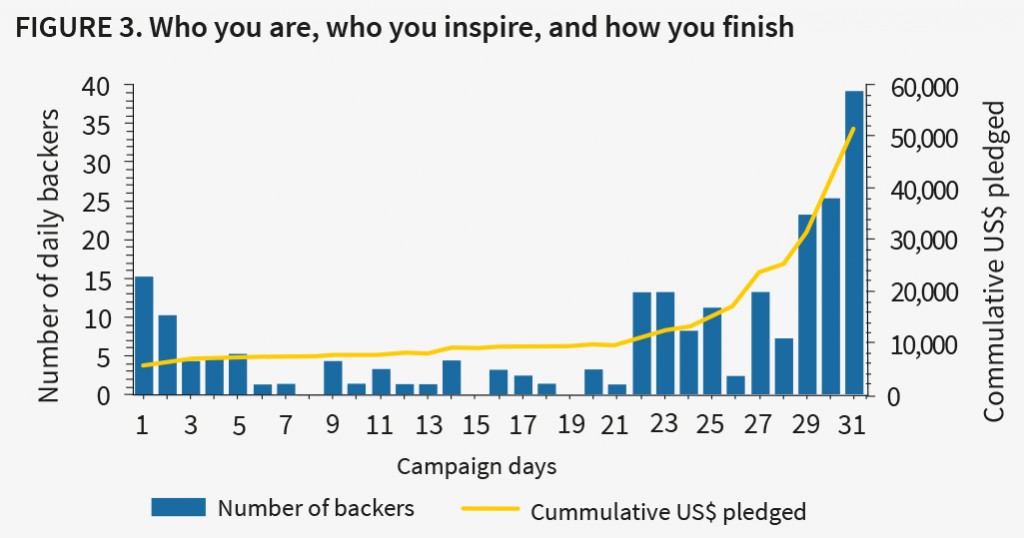

Cullinan discovered this the hard way. After a few days of excitement, the campaign stalled. During the middle two weeks of the campaign only $3,200 was raised. A week before the campaign’s end, Cullinan was $30,000 short of the funding goal. Based on the campaign’s general characteristics and progress, quantitative analysis predicted failure. As researchers, we were lucky to see a counterexample that helped reveal what makes crowdfunding work.

“After a week, people close to me were saying that this campaign has already failed. But we invested lots of time and money on the campaign and I would not go to bed for the remaining three weeks thinking that I gave up on this after a few days.” (Cullinan)

As with many aspects of entrepreneurship, the really interesting phenomena take place at the edge where success and failure hang in the balance. Some crowdfunding campaigns are doomed from the start by poor communication, lack of credibility, or just second-rate projects. Some are almost guaranteed success by a large extant fan base. Somewhere in between, hidden in the datasets, are the projects that should succeed but fail, and the seemingly doomed projects that somehow succeed. Here are the secrets that make the difference.

Secret #1: Success is who you are, not what you say

At the surface, campaign success seems to hinge on superficial factors. The statistics show that investors interpret posted content for professionalism and viability. Spelling errors suggest the project team is not competent. Longer duration campaigns convey a lack of confidence. The statistics show that, at the margin, these factors hinder campaign outcomes.

Another easy mistake is to overcommunicate at the start. This strategy relies on potential backers to figure out what broadcast information to assimilate. Cullinan had even used some pilot testing to arrive at this strategy:

“How I designed my Kickstarter campaign is a direct response to a couple of meetings with potential big supporters. Some wanted to know lots of detailed information, whereas others did not want details at all. Now the campaign covers this spectrum.” (Cullinan)

In the final analysis, however, authenticity makes the difference. Entrepreneurs can manage crowdfunding content as the campaign evolves. Errors can be corrected; images and videos updated or swapped out. But backers are not consistently convinced by cosmetic changes. What they really want is to fund something ‘real’, something authentic.

This was powerfully demonstrated in Doctor Noize’s campaign. Although Cullinan is a creativity-centered entrepreneur, he adopted a professional identity for the crowdfunding campaign. The project site highlighted his track record and business successes, along with a thirty-page business plan including detailed financial analysis. If crowdfunding backers were like traditional investors, this might have worked.

As donations slowed, Cullinan considered cancelling the campaign rather than allow it to fail. Instead, he talked with his advisors about why people supported his creative work. They concluded that backers support authentic individuals rather than professional projects. The campaign needed to be re-humanised. The pitch needed to be personal and authentic rather than professional and polished.

“I bungled the initial campaign phase…I got smarter throughout the campaign to understand the flaws. That triggered me to engage extensively with people from the Kickstarter community. [T]he interactions became very personal rather than product and business focused. And it turned out that this was the right thing to do as I got a lot of responses and started to receive contributions.” (Cullinan)

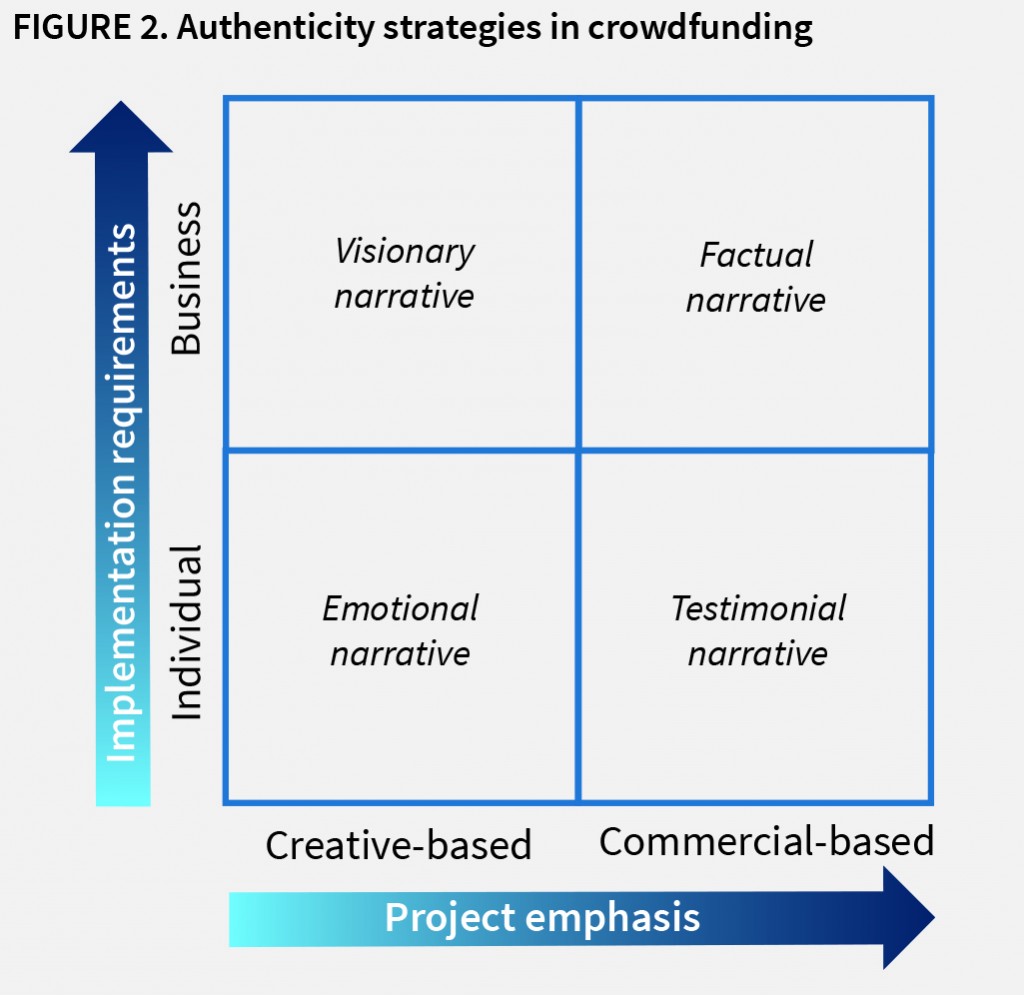

Authenticity comes in many forms. Figure 2 shows the optimal authenticity strategy based on project emphasis and implementation requirement. Creative projects demonstrate authenticity by linking the outcomes to the entrepreneur’s vision and emotions. Commercial projects, which look more like traditional ventures, should emphasise facts and demonstrated team competencies. Authenticity should also reflect the implementation requirements of the project. If the project will require organisational structure, the campaign authenticity requires a specific vision and facts to support it. If the project will effectively be a one-person show, then authenticity derives from the entrepreneur’s demonstrated emotional commitment. The “wisdom of the crowd” resides in rapid assessment of authenticity rather than assessment of project potential. The most valuable currency in a crowdfunding campaign is an authentic narrative tailored to project scope and scale.

Secret #2: Success is who you inspire, not who you know

Networks play a critical role in accessing and assembling capital, especially for seed- and early-stage start-ups. Raising risk capital is seemingly about “who you know”. A large personal network with strong ties leverages network effects and increases access to diverse resources.10 Early studies suggested the same relationship held true in crowdfunding.

The disruptive power of crowdfunding, however, derives from transparent, effectively zero-cost communication. When the communication and interactivity tools of the platform are taken into account, the entrepreneur’s network at the start of the campaign becomes less important. The statistics show that a temporary syndicate of supporters is more powerful than the size of the entrepreneur’s network. Who you inspire is more important than who you know. These syndicates are closely-coupled networks of individuals who promote a particular project for capital injection above alternatives. Frequent use of communication and interactivity tools such as project updates and two-way campaign commentary mechanisms are strongly correlated with success. Crowdfunding supporters are evangelists as much as they are investors or gatekeepers. Successful crowdfunding activity builds ‘a crowd’ rather than passively and randomly tapping ‘the crowd’.

“People might be interested in the project but they are much more excited to have the opportunity to be involved in it with me. So when you go out on the campaign trail and you ‘digitally’ shake people’s hands they suddenly start feeling connected to the project. And then surprisingly people start thinking that this is successful before it actually is.” (Cullinan)

Engagement transforms campaign ‘visitors’ into ‘evangelists’. Regular, open communication with supporters and non-supporters provides insight into what aspects of the campaign are resonating with the crowd. Potential supporters often adopt a ‘wait-and-see’ approach. Without active solicitation of non-supporter feedback, campaigns may become overly insular, relying on the reach of the platform. Potential supporters may be invisible to the campaign and each other. Active communication increases the visibility of committed and potential supporters. By nurturing interaction with and among ‘interested visitors’, entrepreneurs seed a conversation centered around a shared vision, leading to the formation of a project-syndicate.

Secret #3: Success is how you finish, not how you start

Online crowdfunding platforms (OCPs) appear to offer a somewhat mechanised and systematised fund-raising process. Entrepreneurs create the content, sort out the rewards or ownership offers, link up their social media networks, and then push the ‘launch’ button. Because the target stakeholders are, in most cases, either direct or indirect customers, the OCP looks like a shortcut – an efficient way to confirm target market interest while simultaneously acquiring needed resources. This also aligns with the “lean start-up” methodology, in which entrepreneurs are encouraged to run inexpensive, fast experiments to test their value proposition and minimum viable product. For invariably resource-constrained entrepreneurs, OCPs seem almost too good to be true.

To be sure, OCPs have partly democratised small-scale entrepreneurial funding. Eventually, research will help clarify how many OCP-facilitated projects truly owe their provenance to crowdfunding. While we suspect many crowdfunded projects would have obtained funding through other means, at the margin OCPs fund some projects that would be abandoned otherwise.

Here we see yet another dilemma for the entrepreneur. On the one hand, the wisdom of the crowd assesses authenticity rather than project validity. On the other, the entrepreneur needs to build and inspire a syndicate within the crowd rather than passively tap the entire crowd and hope for latent, unrealised investment interest. How do entrepreneurs communicate an authentic identity without missing key crowd-segments?

Our research shows that entrepreneurs use two community interaction strategies to drive project-syndicate formation. Some entrepreneurs surrender to the emergent community and subjugate the crowdfunding campaign to its norms and beliefs. Other entrepreneurs align with the emergent community and strive to co-create the campaign with that community.

“I am connected to my supporters and I am inviting them to my shows but also to take active parts in the product realization due to some offered rewards. Interestingly, the co-creation process was difficult to implement at the beginning of the campaign because there was no activity. However, later throughout the campaign and also after the campaign succeeded, suddenly supporters wanted to actively be part in the production of the project as it is now perceived as a successful campaign.” (Cullinan)

Crowdfunding a creative project requires alignment and adaptation with the nascent syndicate. Again, if the entrepreneur knew the target segment in advance, why bother paying fees to use the online platform? The early days of potentially successful projects enable self-identification by members of a latent backer syndicate. But that is only the start of the process. Entrepreneurs that hope a few self-selected opinion leaders will drive the campaign to success are most likely going to be disappointed. Cullinan used the platform to reach out to his, including influencers, as the campaign drew to a close. He also reached out in person to key supporters and specific referrals they made. Their contributions came through the OCP, but at least some of the footwork was very real.

Entrepreneurs must identify and engage with these influencers, establishing an open and developmental dialogue. The narrative of the campaign may or may not require significant alteration to be aligned with the interests of the syndicate as it forms. Regardless, the entrepreneur needs to actively nurture the growth of the syndicate and either co-create or even re-create the narrative and project elements as the syndicate grows and its interests become clear. The successful crowdfunding entrepreneur invites backers to “join the band” and then works with them to agree on the music to be played. Figure 3 shows how the Doctor Noize campaign succeeded after Cullinan reverted to his authentic creative identity, shook backer hands ‘digitally’, and aligned the campaign narrative to the emerging syndicate.

Ironically, successful online crowdfunding is a social activity at heart. The drivers of success supersede the technology platform and highly-structured process. High quality campaigns may fail; projects lacking key characteristics may still succeed. After all, every entrepreneurial project is uncertain. If people choose to support creative entrepreneurs they have never met, it only makes sense to invest in the campaigns that reciprocate. Maybe it is only fair. Maybe it is karma. Or maybe the (online) crowd is wiser than we thought.

About the Authors

![]() Adam J. Bock is Associate Professor of Management at Edgewood College in Madison, Wisconsin, United States. He studies technology ventures to explain why entrepreneurs commercialise innovations and how they develop new business models. Adam has published peer-reviewed research in Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Journal of Management Studies, and other journals. He is the author of three books on entrepreneurship, including Brilliant Business Models (2016, Pearson). He is the co-founder of four life science companies and mentors entrepreneurs around the world.

Adam J. Bock is Associate Professor of Management at Edgewood College in Madison, Wisconsin, United States. He studies technology ventures to explain why entrepreneurs commercialise innovations and how they develop new business models. Adam has published peer-reviewed research in Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Journal of Management Studies, and other journals. He is the author of three books on entrepreneurship, including Brilliant Business Models (2016, Pearson). He is the co-founder of four life science companies and mentors entrepreneurs around the world.

Denis Frydrych is a Policy Research Associate at Saïd Business School, University of Oxford. His research explores the unique aspects of entrepreneurial crowdfunding. Denis’ research has been presented at leading international conferences and published in Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance and International Perspectives on Crowdfunding (2016, Emerald).

Denis Frydrych is a Policy Research Associate at Saïd Business School, University of Oxford. His research explores the unique aspects of entrepreneurial crowdfunding. Denis’ research has been presented at leading international conferences and published in Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance and International Perspectives on Crowdfunding (2016, Emerald).

References

1. Massolution (2015). 2015CF – Crowdfunding Industry Report. Massolution. Retrieved from: http://www.crowdsourcing.org/editorial/global-crowdfunding-market-to-reach-344b-in-2015-predicts-massolutions-2015cf-industry-report/45376 (Accessed 23.02.2016).

2. A useful general introduction to crowdfunding can be found at: http://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/crowdfunding-guide/index_en.htm

3. Forbes (2015). Trends Show Crowdfunding To Surpass VC In 2016.Retrieved from: http://www.forbes.com/sites/chancebarnett/2015/06/09/trends-show-crowdfunding-to-surpass-vc-in-2016/#47639e9d444b (Accessed 25.2.2016).

4. European Commission (2015). Crowdfunding. Banking and Finance. Retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/finance/general-policy/crowdfunding/index_en.htm (Accessed: 23.11.2015).

5. Doctor Noize (2015). Kickstarter Campaign. Retrieved from: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/doctornoize/phineas-mcboof-crashes-the-symphony (Accessed 24.02.2016).

6. Frydrych, D., Bock, A. J., Kinder, T., & Koeck, B. (2014). Exploring entrepreneurial legitimacy in reward-based crowdfunding. Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 16 (3), 247-269.

7. Frydrych, D., Bock, A. J., and Kinder, T. (2016). Creating Project Legitimacy – The Role of Entrepreneurial Narrative in Reward-Based Crowdfunding. In: Julienne Brabet, Isabelle Maque, and Jérôme Méric (Eds.): International Perspectives on Crowdfunding: Positive, Normative and Critical Theory. London: Emerald.

8. Mollick, E., and Nanda, R. (2015). Wisdom or Madness? Comparing Crowds with Expert Evaluation in Funding the Arts. Management Science, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2207.

9. Colombo, M. G., Franzoni, C., and Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2015). Internal Social Capital and the Attraction of Early Contributions in Crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39 (1), 75-100.

10. Shane, S., and Cable, D. (2002). Network Ties, Reputation, and the Financing of New Ventures. Management Science, 48 (3), 364-381.