Governments around the world are facing increasing pressures on all fronts. From Europe to Japan to the United States, the public sector has had to adjust to a new era of fiscal austerity at the same time as dealing with demands for better services and widespread calls to stimulate economic growth.

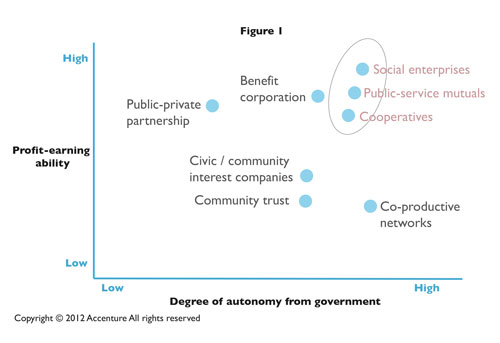

To meet such challenges, public servants have been incubating and hiving off independent organisations designed to provide public services by pursuing a mission of social value realised through a sustainable business model. Though diverse in organisational form and ownership model – from mutuals and cooperatives to community interest companies and social enterprises – they are all hybrid embodiments of the public, private and social sectors. For health and human services in particular, hybrid spinouts offer prospects of scale, performance and innovation that outstrip the well-known limitations of pure-play provision by any single sector.

Consider, for example, NAViGO, which provides mental health and social care services in North East Lincolnshire, England. NAViGO was spun out from the National Health Service in 2011 and is now a non-profit social enterprise owned by its employees. The organisation works closely with its service users to develop innovative solutions for reducing waste and increasing efficiency, and the result has been a business enterprise with fewer managers and less bureaucracy. For fiscal year 2012, NAViGO reported a surplus of £300,000 on revenues of more than £22 million, and the surplus was reinvested back into its operations.

Hybrid organisations can combine the best of the public, private and social sectors. They maintain a strong social mission to deliver various services that the private sector might not be interested in providing, and they rely on business acumen and entrepreneurship to lessen their dependence on government funding. Their goal is improved citizen services and wider economic benefits to the communities in which they operate. In practice, however, public spinouts can be difficult to create and just as hard to manage. How, for example, can they attract the talent they need? What kind of revenue streams should they pursue? Moreover, how can they increase their scale while remaining faithful to their core social mission?

[ms-protect-content id=”9932″]

A Wave of U.K. Spinouts

To answer such questions, we studied public spinouts in the United Kingdom, where the government has actively encouraged the creation of such entities, as well as other hybrid organisations in Europe and the United States. In the United Kingdom, the hope is that by 2015 about one in six public employees will work for a social enterprise or mutual. Since 2010, employees have spun off dozens of independent social enterprises and mutuals, which are typically owned and run by their employees or members. (Note: Because the focus is on social objectives as well as a sustainable business model, the “spinning out” process differs from privatisation.)

In studying those entities, we found that there was no single blueprint, but they typically shared the following characteristics: autonomy from government control, a strong social mission, robust business models (exchanging goods or services for revenue), a non-traditional fiscal philosophy (profits are often reinvested into the enterprise or donated to other social-mission organisations), and a focus on providing public services (such as geriatric care) that fulfil an existing need, particularly within populations that might be vulnerable. Some of the spinouts are large organisations in their own right. A mutual that was spun out from the U.K. National Health Service provides community nursing to 280,000 people and is owned and run by its employees.

In our research, we expected hybrid spinouts to wrestle with the ostensibly competing imperatives of the three sectors. In personal care, for example, how are costs to be kept down while at the same time maximising the frequency and duration of visits with vulnerable clients? It turns out that the architects of some of the most successful hybrid spinouts have built operating models that not only avert negative outcomes but also harness competing motives to propel a virtuous cycle. These organisations actively “square the circle” in four dimensions of management: talent, innovation, growth, and leadership.

1. Talent: combining social ethos and business acumen

One of the biggest challenges facing public spinouts is finding and retaining the right talent. Of course, that’s a difficulty for many companies in general, but it’s all the more acute with hybrid organisations because they require entrepreneurs with business acumen combined with a deep desire to fulfil a social mission. That unique combination can be quite difficult to find in an individual. Consequently, some hybrid organisations have had to grow their own talent in-house.

Consider Greenwich Leisure Limited (GLL), which was formed in the early 1990s to oversee seven local leisure facilities in the London borough of Greenwich. It has since grown to manage more than 90 leisure centres in partnership with 27 local authorities. In 1993, GLL employed 100 contracted staff and had an annual turnover of £5 million. By 2011, those numbers had grown to 1,800 full-time staff (with 3,000 additional part-time and seasonal staff) and annual turnover of £120 million. To accommodate that kind of growth, the organisation has established its own two-year graduate training programme that accepts about 10 to 12 people every year. The programme has been instrumental in helping GLL to maintain a steady pipeline of managerial talent. In fact, almost all of the organisation’s branch managers have participated in it.

To retain talent, many hybrid organisations deploy financial incentives that are based more on group rather than individual performance. That approach will tend to foster greater respect among team members, enhanced self-esteem and perceptions of control, and increased task enjoyment. Another attraction for such individuals is employee ownership. Indeed, many hybrid spinouts have used that as a key component of their employee incentive packages to help foster greater employee engagement and participation in shaping the organisation’s strategy, as well as facilitating the initial transition out of the public sector.

2. Innovation: marrying continuity and adaptation

Frontline employees working with customers are often in the best position to develop innovations for improving the quality of that service, lower its cost, or both. Within a year of being spun out, a healthcare centre in England’s Midlands region was able to achieve productivity gains of 20% on pre-transfer rates, while the quality of clinical outcomes remained the same or improved. Part of that success was attributed to employee innovations that helped drive costs down. Another hybrid organisation – Sandwell Community Caring Trust – was able to slash its overheard costs from 38% to 18% within 10 years of being spun out.

To achieve such impressive gains, hybrid organisations tend to keep their organisational structures flat. That way, suggestions from frontline employees — as well as information from surveys and other feedback mechanisms — will have a far easier time making their way to managers and executives. And that is one of the key benefits of public spinouts: because they have autonomy from the bureaucracy of government bodies, they are able to react more quickly to pursue innovative ideas.

3. Growth: balancing focus and scale

When a hybrid has been spun out, it must figure out how to survive and grow on its own, and the ability to scale up becomes crucial. According to one study, about two-thirds of social enterprises with annual turnover of more than £1 million were profitable, whereas the organisations most likely to suffer losses were those with annual turnover of less than £10,000.

The overriding challenge is that hybrid organisations typically operate on tight margins, such that the loss of a single large client or contract can often spell disaster. Diversification can help prevent such catastrophes. For example, San Patrignano, an Italian hybrid helping rehabilitate substance users, has developed into much a larger venture incorporating a food and wine business, a restaurant, a home design store, and a graphic design agency.

Another option is to consider different types of business models. Sunderland Health Care Associates (SHCA), a provider of domiciliary care services across the north east of England, has grown through a franchising operation that has enabled the spinout to increase its geographic reach. It has set up a separate entity that is responsible for replicating its operations in cities across England. That organisation finances those franchises and oversees them to ensure that they adhere to the appropriate regulations.

4. Leadership: institutionalising individual vision

Not surprisingly, the leaders of successful hybrid spinouts tend to be zealously committed to social and public entrepreneurship. To get things done, they generally have an attitude of “do whatever works.” Many of them have held their positions for a long period of time and may have been among the founders of their organisations. This continuity can help ensure a smooth transition out of the public sector as well as the “growing pains” associated with establishing a new organisation.

However, this strength also presents a challenge in terms of ensuring that individual drive is replicated more broadly across the management team through succession planning. Here, employee ownership can be a very useful tool because it encourages people to take a more active role in the governance of their organisation. Also, the flatter hierarchies discussed earlier will also help: when the distance between the top and bottom levels of the organisation is minimal, executives will tend to have an easier time transmitting their vision, strategy, and core principles through the ranks.

A Mandate for Progress

Hybrid organisations have the potential not only to deliver better public services but also to support and spur the larger economy. According to one study in the U.K., employee-owned organisations generated an annual employment growth of 7.5% in the U.K. from 2005 to 2008. That rate was nearly twice the comparable figure of 3.9% for other enterprises. Given such benefits, policymakers and others would do well to consider ways in which they might remove some of the obstacles that impede public-sector spinouts. Three areas for action of particular significance are careers, capital and competition.

First, one of the biggest challenges for hybrid organisations is finding the right talent. To encourage social entrepreneurship, policymakers might consider a sabbatical programme through which experienced public managers could test and launch their own social enterprises. And social entrepreneurship could be taught at an earlier age if schools and universities integrated the topic into their curricula and vocational programs. Furthermore, a programme modelled on Teach for America could be used to engage recent high-achieving college graduates. Through such a programme, participants would spend a period of time working in a social enterprise, after which they could then have access to various support and employment opportunities.

Second, a large obstacle for hybrids is the difficulty accessing upfront capital investment. The problem is that banks are often wary of making such loans to employee-owned entities. To overcome that, governments should consider rethinking reporting and accounting parameters to create social capital markets. A metric that has been gaining more widespread use is the “social return on investment,” which takes into account the environmental and social value generated by an investment. Such new accounting measures should lead to individual and institutional investors participating more actively in the financing of hybrid organisations. Moreover, investment organisations could help reduce the risks of investing in public-sector spinouts, especially when they are in the early stages of development.

Third, the competitive landscape can also be a huge barrier. Government procurement and the awarding of contracts are often structured in ways that favour large, incumbent organisations. Regulatory and policy changes such as the U.K.’s recent Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 can help to make the playing field more level by requiring decision makers to embrace a broader set of considerations, including social and environmental issues, when awarding public contracts. And local governments can go further by providing assistance in various forms, including management expertise, the temporary loan of employees, and infrastructure support. Some municipalities in northern England, for example, have offered their back office IT facilities to local start-ups.

Where the Public Sector Leads, Others will Follow…

As cooperatives, community trusts, mutuals, and other similar bodies become increasingly viable and successful ways of delivering public services, we are also likely to see businesses and charities embrace hybrid forms. For businesses, the hybrid value proposition centres on their ability to deliver economic value in a way that addresses societal challenges. For charities, the hybrid model potentially represents a more sustainable route to scale.

For example, UK-based BeOnsite began as the corporate social responsibility arm of Lend Lease, a property company, focusing on support and training for marginalised groups. To improve its ability to access a wider range of funding streams, BeOnsite is spinning out of the private and into the voluntary sector. In the United States, the organisation Seniors Helping Seniors (SHS) started life as a charity where senior citizens provided domiciliary care services for other elderly people. To expand its reach, SHS began franchising itself as a private-sector entity. SHS now operates more than 100 franchises across the United States.

For policymakers, business leaders and charity executives, the hybrid model provides a compelling option for combining what once were seen to be competing imperatives. Furthermore, they offer lessons for managers of all enterprises that are struggling to retain top talent, spur innovation, find new avenues of growth, and develop the leaders of tomorrow. By learning from these examples and building on their success, organisations can start to realise the best of all worlds.

About the Authors

Tim Cooper is a senior research fellow with the Accenture Institute for High Performance. Matthew Robinson is a managing director with the Institute. They are based in London.

[/ms-protect-content]